Supplementary Table 1 (docx 21K)

advertisement

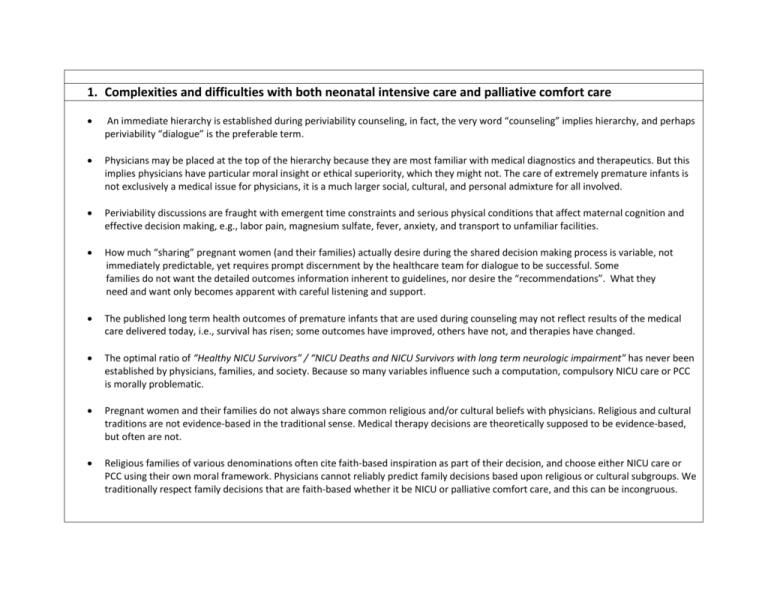

1. Complexities and difficulties with both neonatal intensive care and palliative comfort care An immediate hierarchy is established during periviability counseling, in fact, the very word “counseling” implies hierarchy, and perhaps periviability “dialogue” is the preferable term. Physicians may be placed at the top of the hierarchy because they are most familiar with medical diagnostics and therapeutics. But this implies physicians have particular moral insight or ethical superiority, which they might not. The care of extremely premature infants is not exclusively a medical issue for physicians, it is a much larger social, cultural, and personal admixture for all involved. Periviability discussions are fraught with emergent time constraints and serious physical conditions that affect maternal cognition and effective decision making, e.g., labor pain, magnesium sulfate, fever, anxiety, and transport to unfamiliar facilities. How much “sharing” pregnant women (and their families) actually desire during the shared decision making process is variable, not immediately predictable, yet requires prompt discernment by the healthcare team for dialogue to be successful. Some families do not want the detailed outcomes information inherent to guidelines, nor desire the “recommendations”. What they need and want only becomes apparent with careful listening and support. The published long term health outcomes of premature infants that are used during counseling may not reflect results of the medical care delivered today, i.e., survival has risen; some outcomes have improved, others have not, and therapies have changed. The optimal ratio of “Healthy NICU Survivors” / “NICU Deaths and NICU Survivors with long term neurologic impairment” has never been established by physicians, families, and society. Because so many variables influence such a computation, compulsory NICU care or PCC is morally problematic. Pregnant women and their families do not always share common religious and/or cultural beliefs with physicians. Religious and cultural traditions are not evidence-based in the traditional sense. Medical therapy decisions are theoretically supposed to be evidence-based, but often are not. Religious families of various denominations often cite faith-based inspiration as part of their decision, and choose either NICU care or PCC using their own moral framework. Physicians cannot reliably predict family decisions based upon religious or cultural subgroups. We traditionally respect family decisions that are faith-based whether it be NICU or palliative comfort care, and this can be incongruous. A significant but unquantified proportion of families and healthcare providers do not hold standard ethical considerations such as justice, beneficence, respect, and autonomy in the same framework for infants as compared to children or adults. Physicians and other healthcare providers who have had a premature infant (palliative comfort care or NICU care) may find it challenging to participate in periviability counseling in an acceptably fair and impartial manner. 2. Complexities and difficulties with palliative comfort care How can the “Best interests of an infant” ever be death? Life and death are incommensurable outcomes. Perhaps any sentient life is better than none at all. Premature infants who might be healthy in the long term will die without the benefit of NICU care. Which newborns? How many? What proportion? We are unable to reliably identify such infants in the delivery room. Palliative comfort care is a decision when in process, is problematic to reverse. It might be preferable in some circumstances to withdraw life support rather than withhold life support. Palliative care can be perceived as “giving up”, and its duration and expected course can be variable, possibly creating discomfort. Quality of life can be acceptable or even good for children with long term neurologic and other chronic health issues. Physicians can overestimate the effects of perceived disabilities and be unduly negative during counseling. Medical science cannot advance if the edges of modern NICU care are not pushed. Therapies might only improve if we try to expand the margin of treatments, which is imbedded in the history of neonatology. NICU and infant care are approximately 2% of total yearly healthcare expenditures in the United States, so financial responsibility might not be a relevant issue considering how much we spend on adult medical care. 3. Complexities and difficulties with neonatal intensive care “Best interests of the infant” can trump “Best interests of the woman and family” and for disputable ethical and social reasons. The effects of neonatal and pediatric chronic illness can have significant adverse effects on parents and siblings. “Best interests of a human being” are not held equivalent to “Best interests of a person” by some pregnant women, families, and health care providers. Some people believe that this distinction is critical, e.g., they would submit that an infant with a severe anomaly like anencephaly is a “human being” but not a “person” and thus does not have the same rights and status. They may view extremely premature infants in a similar framework. The “line of demarcation” in neonatology disputes is often poorly defined, arbitrary, and thus illogical under scrutiny. If a NICU mandates resuscitation at 23 0/7 weeks, what if a pregnant woman is 22 weeks, 6 days and 23 hours? Is palliative comfort care “ethical” for one more hour? If a NICU mandates palliative comfort care at 22 weeks but allows NICU care at 23 0/7 weeks, what if a pregnant woman wants full NICU care and is 22 weeks and 6 days? If a child is considered to have a “significant neurodevelopmental disability” only if the Bayley III Developmental Quotient is <70, what if the score is 71, is that “normal neurodevelopment”? Less immediate neurodevelopmental impairments are strongly associated with extreme prematurity, e.g., autism, learning disorders, and behavioral problems. These are not considered significant neurodevelopmental disabilities by some physicians and might not be adequately considered during counseling. “Risk” is the product of harm and the probability it will occur. “Uncertainty” means we do not know what will happen. Pregnant women and families generally understand the difference between risk and uncertainty related to extreme prematurity; physicians may not appreciate this distinction. Some physicians mistakenly believe that palliative comfort care for extremely premature infants violates state or federal law, and do not fully understand Baby Doe regulations, and the Born Alive Infant Protection Act (BAIPA). Care of premature newborns is a significant portion of the estimated $60 billion spent on infants in the first year of life in the USA (2014). This can divert resources from more cost-effective interventions that benefit a larger pool of children like universal prenatal and well-child care, breast feeding support, and vaccinations. Healthcare budgets are limited, and insurers are moving to capitation and finite resource allocations. Physicians must now help decide the best distribution of limited resources to enhance whole population health. The pain, suffering, and hidden morbidity of resuscitated infants who die in the NICU days, weeks, even months after birth, is generally not reported or discussed forthrightly. Palliative comfort care and therapeutic abortion rights can be conflicting and thus viewed by some as morally misaligned. Abortion is legal in some areas of the United States at 22, 23, 24, and 25 weeks gestation, so how might a physician logically explain to a pregnant woman the potential variance between guidelines of NICU care versus palliative comfort care versus pregnancy termination? The out-of-pocket cost of NICU care and direct follow-up expenses can be overwhelming for families who might not receive reasonable assistance. Financial, medical, social, and community support for the NICU graduate is often far short of what the family requires for months and years after NICU discharge. Ethical, financial, and emotional burdens for the family are enormous compared to the physicians and other healthcare providers who bear little or no personal risk participating in NICU care. If a physician has no immediate personal downside to insisting upon NICU care, then there is a diminished relational ethical basis to this decision, it might become an amoral act for the physician. It is families who bear the principal burden of risk and long term stress, so it is families who make moral decisions. Physicians have real, perceived, and possibly subconscious conflicts of interest during periviability counseling, i.e., their careers and professional interests and income are dependent in part upon neonatal intensive care. Neonatologists often target their research and subsequent publications at various disorders of the premature infant which unfold only if babies are admitted to the NICU. Many NICUs are profit centers for hospital organizations. One of the largest group medical practices in the United States is a growing forprofit private neonatology and perinatology enterprise that is publically traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Table 5. 18 years of periviability guidelines and dialogue at Providence St. Vincent Medical Center 1996-2013 with highlights of the principle complexities, controversies, and learning opportunities related to the birth of extremely premature infants. NICU – neonatal intensive care unit.