- UVic LSS

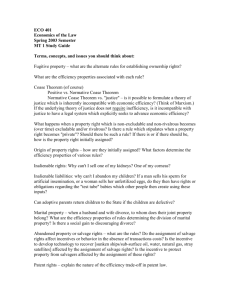

advertisement