Where Do We Go From Here?

advertisement

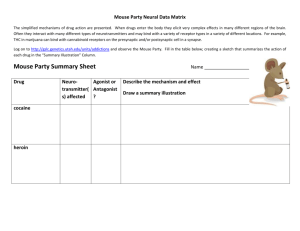

Justin Edwards Writing 340 Marc Aubertin 6 December 2013 No Hands: The End of the Handheld Computer Mouse? Engineers are constantly at work researching and developing the next big revolution that will improve and simplify the daily human lifestyle. It is safe to assume that as society continues to advance, these newer technologies will surpass theory and become commonplace, replacing some older devices for more efficient and convenient models. Many have witnessed this evolution firsthand with the transition from pagers for the faster, more instantaneous cell phone, or the CD player for the sleek and far more portable iPod. Computers are no stranger to these remodeling and design improvements, and the same can be said of a device that has become a technological necessity: the mouse. The mouse has evolved and has experienced great changes, and despite its growing age among developing technologies, it has thus far been able to retain its value to society, shedding only a few technological layers with each redesign. However, have technological advancements reached a critical turning point in which the computer mouse finds itself losing its form completely? Based on the ways in which the ergonomics of the computer mouse have evolved and observing the trends of devices in development, the computer mouse is on a path of minimalism and will eventually lose its physical form. Ergonomic Evolutions In order to understand where the mouse is going, it is important to have a general idea of where it is coming from. The computer mouse known today hardly resembles that of the original model. During the early 1960s, Dr. Douglas C Englebart had the vision of creating a user friendly way of moving across a computer screen in the x-y planes, and in 1968, Englebart patented a device that he more formally termed the “X, Y position indicator for a display system” (Englebart). Later on it would take the short hand of “mouse” for the cord that ran out from the back of the device. As seen in Figure 1, the mouse he created was little more than a wooden block with two wheels – one for each axis – but at the time, showed greater promise than anything that had been developed. His later developments to this initial design for the Fall Joint Figure 1. Englebart Prototype Mouse [photo courtesy of ComputerHistory.org] Computer Conference of 1968 would gain his now three button mouse presentation the title of “Mother of all Demos” (Englebart). Frrom this moment on, the computer mouse would continue to evolve and develop to become cheaper, more effective, and of course, more convenient. The mouse in the homes of most today can be attributed to a few key design changes. The first was the addition of the trackball to the bottom of the mouse to provide greater screen mobility to the user to move across the screen without needing to move the entire arm. The trackball mouse was released in 1974, developed by Jean-Daniel Nicoud and became the modern single-ball, two-button mouse (Telnames). Following the trackball, the development of a cheaper affordable mouse could be seen as the next advancement in design. Unlike most of the prior models that had prices in the thousands of dollars, Hovey-Kelley under contract to Apple would unveil a design that designer and historian Benj Edwards says, “…sets the stage for cheap, reliable consumer mouses that everyone can afford.” As the 1990’s began, multiple breakthroughs in technology would change the mouse the world knew forever. In 1991, Logitech develops the first mouse to use radio frequency (RF) transmissions, a far better alternative than the use of infrared (IR), which required line of sight and a base station on the computer. In addition, Carmen Carmack, technical communicator and writer, noted that the RF mouse was less expensive, light weight, and consumed less power which allowed it to be battery operated (Brain). The most influential and crucial design change however occurred in 1998 when the mouse gained the ability to track space without the necessity of a special pad or surface. The optical tracking sensor having now become LED based, mice could practically and efficiently be used under a wide variety of circumstances, making an almost essential to computer users. Reasons Behind Change How then can the claim be made that the mouse is on the verge of losing its physical form after having advanced so far in its design as to be usable to everyone, almost everywhere? Under closer analysis, the revolution presented above addressed three basic needs of the technological consumer. Primarily, the mouse was the newest piece of technology and served a function that no other device on the market at the time could perform well. It was the “pointing device and cursor” as well as “a prerequisite to the windows operating system” (The Importance of the Mouse), in essence making the first step in any design endeavor: identifying and solving a problem. From here, the next need met was to make the mouse affordable to the common consumer. Referencing again the 1974 Mac mouse, the design and materiality of the device reached a ratio under which it became possible to lower the consumer cost out of the thousands of dollars to under one-hundred dollar. Finally, with necessity of design and the benefit of new technologies came the opportunity of ergonomic remodeling: the development of the shape of the mouse to contour to the hand as well as its wireless capabilities. Considering the form of the first mouse, mice of today have all taken on a shape that is easy to hold and maneuver, and without the need of a cord or line of sight, have greatly contributed to the work efficiency and comfort of the user. These three elements in mind, it leaves significant evidence that as new problems arise and newer technologies become available and affordable, the usefulness of the mouse will fall into question, and this process has already begun. One problem that designers have been facing and continue to work against is the increase of carpal tunnel and other musculoskeletal malfunctions. According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), carpal tunnel syndrome occurs when the median nerve, which runs from the forearm into the palm of the hand, becomes pressed or squeezed at the wrist, and while most prevalent in assembly workers, does occur in those who frequently use a computer. As many businesses have long since transferred to computers to manage and maintain business, redesigning the mouse has become necessary to improve the posture of the hand in order to counteract the risks of developing carpal tunnel. However, according to studies conducted in International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, a relationship was found between mouse use and symptoms in the neck, with findings that support the hypothesis that mouse use may contribute to musculoskeletal injury of the neck and upper regions (Burgess-Limerick, Cook, and Chang). This being the case, alternatives to the physical mouse begin to show promise towards the better health of the computer user. Not only is the modern consumer in search of a mouse that will improve their lives, but they search to bring the cutting edge of technology into daily interaction. This quest for novelty has been witnessed at each successive release of the latest iPhone. With the new comes the promise of the fastest, most efficient, most appealing of its kind on the market to date. In response to Moore’s Law – the number of transistors on integrated circuits will double every two years – David House, executive of Intel stated that computer power would double every 18 months, and though this rate is slowing down, new releases do not require dramatic changes in order to inspire sales (Peckham). And this hunt for the newest product on the market is not bad for the consumer. In fact, according to C. Robert Cloninger, the psychiatrist who developed personality tests for measuring the “novelty trait”, said “Novelty-seeking is one of the traits that keeps you healthy and happy and fosters personality growth as you age” (Tierney). In terms of computing and the computer mouse, introductions of novelty have been occurring sporadically, but in recent years have been hastening in development. Innovative Solutions Alternatives to the standard computer mouse are making their way out of developmental stages and onto the consumer market, some which already lose the physical form of the mouse. Many of these new solutions are getting smaller, such as Logitech’s latest addition, the Cube mouse. Seen in Figure 2, the Cube fits well within the palm, and functions with the use of only a few fingers rather than the whole hand, which according to Kevin Hall, journalist for Dvice, “ works so well at your fingertips as that's the point — it doesn't care that you have a whole hand” (Hall). This statement is not made in haste, as laptops have Figure 2. Logitech’s Cube Mouse [photo courtesy of Kevin Hall of Dvice.com] done away with the need for little more than a finger to operate the functions of the mouse by means of a track pad, and with the direction of touch-based technology, the mouse is becoming less necessary for the average user. Touch screens have made it possible to interact with the digital environment and navigate the operating system without anything more than your hands. However, neither minimizing the mouse nor touch screens will replace the computer mouse. In mineralization of the mouse, you eventually hit a cap at how small the mouse can be before it loses functionality, efficiency and comfort. When it comes to touch screens, Mikko Tikkanen mentioned that “Whereas touch-screen rock the handheld world, computer mouse reigns as the sole emperor of the desktop computing.” This statement rests on the idea that when it comes to precision detail and design in the digital space, the touch screen has yet to be able to function at that level of detail and clarity. For this reason the mouse still remains fixated to the right (or left) hand of the computer user. However, these designs are leading society towards a new age of computing, and there are some devices and theories that show great promise in replacing the mouse. New technologies now on the market and in development are setting up to replace the way the average user interacts with their computer. Sensory devices create the first half of this exploration towards mouse-less computing. Devices like the Microsoft Kinect and the Leap Motion offer strong solutions of interacting with the digital environment with greater levels of technicality and precision that your average touch screen. There are those who would suggest that these devices tire out the body and make long continuous work far more difficult to perform. Tech reporter James Plafke makes the argument that even an in-shape person would have troubles with long use of the leap and states “…until the Leap can get itself sorted out… keep your fancy gaming mouse plugged in.” However, this move towards hands free devices does solve the issues of carpal tunnel and other musculoskeletal disorder while introducing innovative technologies. Another such sensory device is vision based interpretive computers, in which computers are designed with perceptive user interfaces, where the computer “is endowed with perceptive capabilities that allow it to acquire implicit and explicit about the user and their environment” (Argyros and Lourakis). This process translates the 2D and 3D gestures of people and tracks the motions on the screen of the computer, thus again, eliminating the mouse. Their research concluded that their interface could be used as a virtual mouse, though the extent to which this could be developed for the general consumer was not made evident. The other half of these non-mouse explorations is focused on ways in which thoughts can be directly transmitted into the action of clicking a mouse. Mind Technologies’ “Mind Mouse” is a headset that effectively removes the need to click a mouse by using the thought of the click to control the desired response on the computer screen. In Figure 3, the mind mouse is displayed on the head of an individual that is playing a computer game, but does so without the use of his hands by focusing his energies into thought of the actions he would have had to click with a mouse. This alternative boast incredible potential to change the way we engage with the digital Figure 3. Mind Mouse in Gaming [photo courtesy of singularityweblog.com] environment, but not only for the sole purpose of clicking. The device also allows one to compose an email and send it via thought, a feature that one blogger observantly notes “…is especially beneficial to people with disabilities who have problems with communicating. For the first time in their life, many disabled people will be able to operate a computer and communicate via email” (“Socretes”). While the technology is still being further developed and adjusted to better communicate through hair follicles and become more affordable to the consumer, the Mind Mouse also successfully removes the need for a computing mouse. Where Do We Go From Here? So is it time to say goodbye to the computer mouse? Though the trends do predict that there will indeed come a in which all household rodents will be unwanted, it may be too hasty to get rid of the mouse. Perhaps Plafke put it best and we should hold onto our computer mice for a while longer. The technologies are out and developing to replace the mouse, however the time in between still does not have a set date. Instead, it seems more likely that society continue to move in the pattern of behavior it is most familiar with and evolve with the technology as it is developed over time. Keeping current with the latest innovations will provide temporary solutions to the physical strains of using the device, and in time, may remove the strain altogether. It is clear to see that the mouse will someday be replaced by an alternative source of computing that boasts greater ergonomics, functionality and innovation to the user. And from the projection of technological developmental trends, it does not appear too long from now. Works Cited Argyros, Antonis A., and Manolis I. A. Lourakis. "Vision-Based Interpretation of Hand Gestures for Remote Control of a Computer Mouse." Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Volume 3979, Pages 40-51. 2006. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. Brain, Marshall, and Carmen Carmack. "How Computer Mice Work." HowStuffWorks. N.p., 24 Apr. 2000. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. Burgess-Limerick, Robin, Catherine Cook, and Sungwon Chang. “The prevalence of neck and upper extremity musculoskeletal symptoms in computer mouse users.” International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. Volume 26, Issue 3, Pages 347-356. September 2000. Web. 16 October 2013. "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Fact Sheet.”: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). N.p., July 2012. Web. 17 Oct. 2013. Dainis. "Unusual Computer Mice You Probably Haven’t Seen Before." Hongkiat.com. N.p., 2010. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. Englebart, Christina. "Father of the Mouse." Doug Englebart Institute. N.p., Aug. 2008. Web. 12 Oct. 2013. Edwards, Benj. "The Computer Mouse Celebrates Its 40th Birthday." PC Advisor. N.p., 13 Dec. 2008. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. Hall, Kevin. "Hands-on with Logitech's Adorably Tiny Cube Mouse." Dvice. Dvice, 10 Jan. 2012. Web. 17 Oct. 2013. Peckham, Matt. "The Collapse of Moore's Law: Physicist Says It's Already Happening."Time. Time, 01 May 2012. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. Plafke, James. "Leap Motion Review: Is It Time to Replace the Mouse?" Extreme Tech. N.p., 22 July 2013. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. "Socretes" "Mind Technologies’ Mind Mouse And Master Mind Thought-Controlled Software." Singularity Weblog. N.p., 2010. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. "The Computer Mouse: A Timeline." Telnames. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. "The Importance of the Mouse." ChidoWare. N.p., 2009. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. Tierney, John. "What’s New? Exuberance for Novelty Has Benefits." New York Times. New York Times, 14 Feb. 2012. Web. 2013. Tikkanen, Mikko. "Killing the Mouse. And No, It's Not Touchscreens." Mint Usability. N.p., 10 July 2009. Web. 17 Oct. 2013.