Saint Anselm`s a priori Ontological Argument Or The Ontology of

advertisement

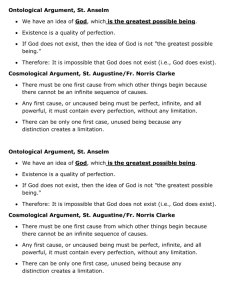

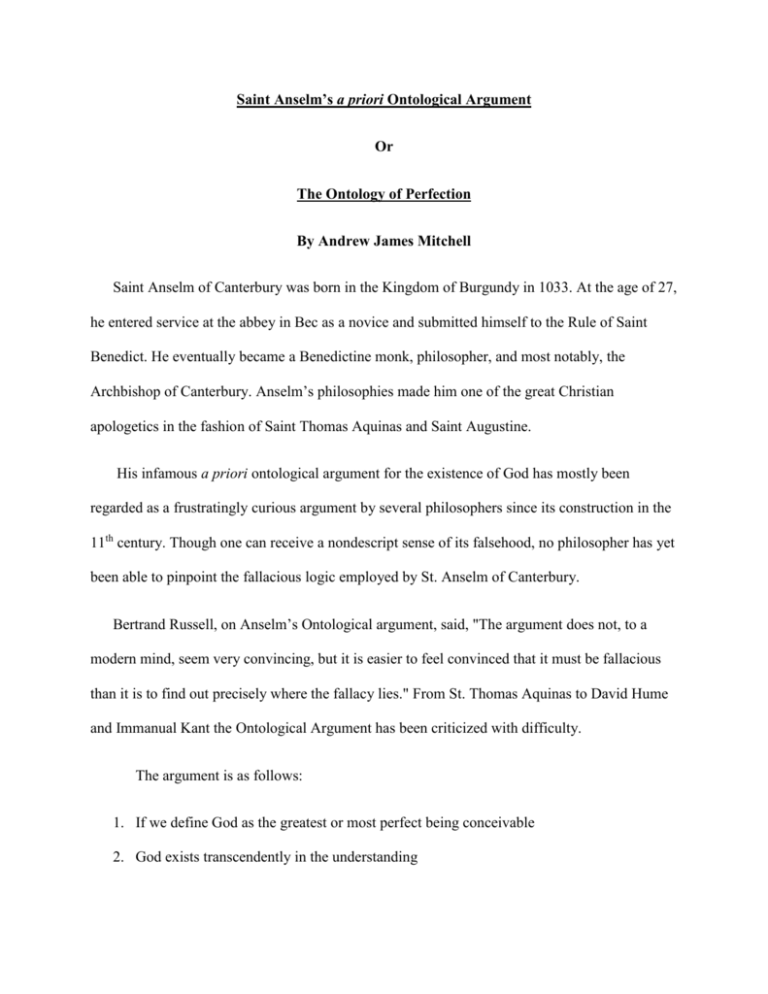

Saint Anselm’s a priori Ontological Argument Or The Ontology of Perfection By Andrew James Mitchell Saint Anselm of Canterbury was born in the Kingdom of Burgundy in 1033. At the age of 27, he entered service at the abbey in Bec as a novice and submitted himself to the Rule of Saint Benedict. He eventually became a Benedictine monk, philosopher, and most notably, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Anselm’s philosophies made him one of the great Christian apologetics in the fashion of Saint Thomas Aquinas and Saint Augustine. His infamous a priori ontological argument for the existence of God has mostly been regarded as a frustratingly curious argument by several philosophers since its construction in the 11th century. Though one can receive a nondescript sense of its falsehood, no philosopher has yet been able to pinpoint the fallacious logic employed by St. Anselm of Canterbury. Bertrand Russell, on Anselm’s Ontological argument, said, "The argument does not, to a modern mind, seem very convincing, but it is easier to feel convinced that it must be fallacious than it is to find out precisely where the fallacy lies." From St. Thomas Aquinas to David Hume and Immanual Kant the Ontological Argument has been criticized with difficulty. The argument is as follows: 1. If we define God as the greatest or most perfect being conceivable 2. God exists transcendently in the understanding 3. And if this conceived God were the most perfect or greatest being he must also exist imminently. 4. Therefore, God exists. The problem lies in the first premise. Many philosophers have focused their attention on the “conceivable” aspect, yet the obvious definition lies in perfection. Take these two statements: 1. God is the most perfect being. 2. God is conceivable. Although the second premise is key to the Ontological argument, the first premise is where the intrinsic fallacy lies. It is logically impossible to define God as the most perfect being. When something is the maximum of an ideology it is the embodiment of that ideology and the two become near synonyms for each other. The first premise defines God as perfection and defines perfection as God. Near synonym fallacy: 1. If we define God as the most perfect being to ever be conceived 2. We denote that God is the embodiment of perfection 3. We fail in properly defining God by using a near synonym or rhetorical tautology If God were not the embodiment of perfection, it would be logically sound to suggest that the existence of perfection was inherited by God by a greater or more perfect source, making it impossible to define God as the most perfect or greatest. Even if we could define God as the greatest or most perfect being, we would contradict ourselves in the understanding of the ideology of perfection. Perfection is an unachievable paradox and contradiction, in which its mere premise is illogical. My argument is as follows: 1. If perfection is static and it lacks the inability to progress, then perfection is imperfect due to its limits and inabilities. 2. If perfection is dynamic than it would remain in a state of imperfection due to its ability to self-improve and progress. 3. Perfection is imperfect and intrinsically contradictory, therefore perfection cannot exist. Perfection as implied by Anselm is impossible to achieve. The premise of defining God as the most perfect being conceivable is the foundation of the Ontological Argument whose conclusions rely entirely upon its first clause. If perfection is impossible to achieve, inferring ones imminence from their transcendence is a false premise fallacy. 1. If we define God as the most perfect being to ever be conceived 2. And God’s imminent existence relies on his perfect transcendence 3. Yet perfection can never be logically achieved 4. Then God’s imminent existence is not contingent upon his transcendence Although my argument may be fallacious in and of itself, the arguments against the Ontological argument are numerous in several different philosophers. Douglas Gasking proposed this argument in opposition to Anselm’s argument: 1. The creation of the world is the most marvelous achievement imaginable. 2. The merit of an achievement is the product of (a) its intrinsic quality, and (b) the ability of its creator. 3. The greater the disability (or handicap) of the creator, the more impressive the achievement. 4. The most formidable handicap for a creator would be non-existence. 5. Therefore if we suppose that the universe is the product of an existent creator we can conceive a greater being — namely, one who created everything while not existing. 6. Therefore, God does not exist. However, I feel like this argument makes assumptions to a similar degree as Saint Anselm. The premises in Gasking’s argument assume that the creation of the world is the most marvelous thing or that there was a creator in the first place. Both arguments depend on the subjective willingness of a society to agree with such bold assumptions. I feel like the modern role of teaching Saint Anselm’s a priori Ontological argument can be an example of Sophistry. By teaching the Socratic Method of Teaching, we can challenge future philosophy students to analyze the Ontological Argument in a Socratic way, and in doing so, express to them the true power of Analytical Philosophy.