Kat`s lecture notes Day 5 – Producing the Spoken word Word finding

advertisement

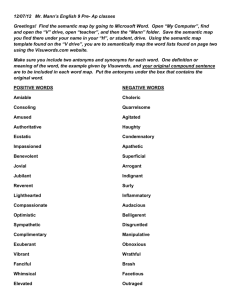

Kat’s lecture notes Day 5 – Producing the Spoken word Word finding in Aphasia Almost all aphasic people have some degree of word finding difficulty or anomia. This results in hesitancies, blocks, omissions and speech errors. Aphasic people often cite word finding as their major problem and a priority for therapy. Below are some typical examples of aphasic word finding errors. Most occurred during picture naming tasks, which enable us to compare the error to a known target. Target anchor Production for holding the sleep steady when its sunk in water Classification Circumlocution iron Hoover bus Sarabang semantic error/paraphasia mixed error dart Dark table kurzle, kazle, tazle, tayzle, table phonological error or literal paraphasia conduite d’approche jacket Helicopter verbal paraphasia onion Thustle Neologism Failure point Knows meaning. Can’t access phonology Partial semantic knowledge Phon. Distortion with a sem error (charabanc) Impaired phonology Impaired phonology Unrelated to target! Unrelated to target What would happen if any of these stages failed? Impaired object recognition Recognition problems, or agnosias, are different from naming problems. There is an example from Oliver Sack's book, 'The man who mistook his wife for a hat'. Sacks asks Dr P to name a glove. As he cannot recognise the object he cannot do this. Instead, he describes it: ‘a continuous surface infolded on itself. It appears to have ... five outpouchings'. Later in the session Dr P accidentally slips the glove over his hand and immediately exclaims "My God its a glove'. He had Visual Agnosia, or an inability to recognise objects from sight. Despite this, he could see & describe them. He could also recognise from touch. Impaired access to the semantic system or damage within the system itself This leads to a poor understanding of objects/words, eg the person may not recall the function of an item or its relationship to other objects. We expect semantic errors in production (eg calling an iron a hoover). If the semantic system is impaired, comprehension will also be poor (as we assume that just one semantic system serves both production and comprehension). Word production will be affected by semantic variables, such as imageabilty. There is good evidence that people with aphasia have problems with semantic access rather than a difficulty within the system itself. This makes them different from people with dementia (Jeffries and Lambon Ralph 2006). Loss of access to the phonological output lexicon Here the person knows the meaning of the word, but cannot access its phonology. The person may circumlocute, or describe the blocked word (see table above for an example of circumlocution). A phonologically related word (or non word) may be produced instead of the target. Access to the POL is influenced by frequency, ie high frequency words are typically named better than low frequency words. Problems at this level often reflect blocked access to words, rather than a loss of words in the POL. Evidence: o naming is often helped by cues, eg where we supply the first sound of the word o naming is often inconsistent, ie an item may be named on one occasion but not on the next A problem with phonological assembly (eg Franklin et al 2002) Target words are distorted in production, eg segments may be omitted, substituted or exchanged. There may be conduite d'approche, where the person gradually gets closer to the target via a series of phonological errors. Length could be a factor – with longer words being more impaired than shorter words. Fluent, effortless articulation shows that it is not a motor problem. People with Conduction Aphasia are thought to have a problem at this level of processing. A problem with the motor stages of production This will be marked by poor organisation or execution of speech movements. There may be hesitant, groping articulation, with dyspraxia or dysarthria. This is strictly a speech problem, rather than a naming problem. Some questions to ask Is word retrieval failing? What is the extent of the problem and does it impede everyday communication? Is word retrieval a priority for the aphasic person? Why is word retrieval failing, in terms of the level of breakdown? What helps? Is the person using any strategies and what strategies might be used? A Case Example: RS (Marshall et al 1990) RS was a 45 year old company director who acquired aphasia after a left CVA. His speech was hesitant with word finding problems. He flagged these up as a priority for intervention. Observations on his dialogue: There are a number of points in the conversation where RS experiences word finding difficulties, causing hesitancies and word substitutions. Most of the words that he uses seem to be very high frequency (although he uses these to good effect). When he has to access a specific term (such as ‘bank’) his problems emerge. Word finding is not obliterated. He may retrieve a word after a delay or come up with a close alternative (such as ‘fee’ for ‘offer’). R has some good strategies for getting round his problems (such as ‘goodbye’ for the concept of redundancies). R’s comprehension seems good. He shows understanding of specific and abstract words (such as ‘staff’ and ‘offer’). Assessment Plan Tests aimed to find out: The extent of R’s naming problem Whether he could be cued Where word retrieval was breaking down: Semantics? Phonology? Tests of semantic knowledge Our model assumes that we have just one store of semantic knowledge which we access on input and for output. We can therefore use input tests to explore semantic knowledge. Here are the results of some semantic tests with RS Pyramids and Palm Trees (all picture version) 3 errors (within normal limits) Spoken word to picture matching 98% Synonym judgements with concrete words 95% Judging picture names* 100% *R was shown a picture and offered a name that was either correct or semantically related to the target. He had to accept or reject the name. R shows good understanding of pictures and concrete words. It seems that his naming problem is not primarily due to a semantic impairment. In line with this he does not make semantic errors in naming, and cannot be tricked into making them. Test of phonological knowledge 30 pictures were presented for naming. If R could not think of the work he was offered a cue (eg /l/ for lion). Occasionally the therapist miscued him (ie /t/ for lion), to see if he could be ‘tricked’ into making semantic errors. R named 10 pictures correctly. Most of his errors were failures to respond. He found correct phonological cues helpful, but did not respond to miscues. Is language breaking down at the level of phonology? We already have one piece of evidence here. R could be cued with the first sound of the word. This suggested that the phonological representation may be retained in the POL, but difficult to access. There was some more evidence. R was asked to read a number of regular and irregular words aloud. He performed perfectly. It seems that he could produce word phonologies as long as he was provided with the written word form. The fact that he could read irregular words shows that he was not simply using GPC. Conclusions It looks like the semantic system is relatively ok (good performance on semantic tests, at least with concrete items). The Phonological output lexicon also seems preserved (response to cues, reading aloud). R can also articulate (spontaneous speech, reading aloud). We therefore concluded that the problem lay in the link between the semantic system and POL. Picture naming 30 pictures were presented for naming. If R could not think of the work he was offered a cue (eg /l/ for lion). Occasionally the therapist miscued him (ie /t/ for lion), to see if he could be ‘tricked’ into making semantic errors. R named 10 pictures correctly. Most of his errors were failures to respond. He found correct phonological cues helpful, but did not respond to miscues. Moving into Therapy Therapy took advantage of two processing strengths: the ability to make semantic discriminations between related words the ability to read aloud Therapy task: matching a picture to one of 5 written related words, eg for the target ‘television’ the pictures might show: a radio, Hi Fi, television, computer & camera. After RS selected the target word he had to read it aloud. Thus RS accessed the phonological form of the word, in the context of making a semantic decision about it. We hoped that this might re-build the links between semantics and phonology, and so improve naming. 25 words were treated in this way, in about 3 hours of therapy. RS was consistently successful on the therapy task. Feedback was used to discuss the differences between the target and foils. Results (on a picture naming task): pre treated words 8/25 untreated words 8/25 naming therapy foils - post 20/25 10/25 11/12 follow up (one month later) 18/25 9/25 - Therapy recovered access to the phonologies of treated words and perhaps related foils which appeared in the treatment tasks (the lack of a baseline score requires caution here). The improvement was well maintained. Generalised access has not occurred, as indicated by the static performance of the controls. A follow up study showed that RS could benefit from this type of task even when self administered as a home programme, and that effects were long lasting. We hypothesised that therapy worked by enabling RS to re-connect semantics with phonology. A phonological approach to naming therapy: GF (Robson et al 1998) GF had a left hemisphere stroke resulting in fluent but meaningless speech (jargon), eg: I was quite erm that’s why I can’t get weyerd keep ... erm makes me very um here up here makes him all /s/ all mingsing but these come and I can’t it might be because I had another setoid no sort of um I mean but when you cough you different but when you right you lie to her ...’ (replying to a question about her holiday) Assessment results: Pyramids and Palm Trees Spoken word to picture matching Auditory synonym judgements (concrete) Naming pictures Reading aloud picture names (reg and irreg) 4 errors (near normal) 39/40 87% 1/40 (awareness of failure) 10/40 Response to cues: When GF failed to name a picture she was offered either a semantic or a phonological cue. Semantic cues were useless (GF was irritated by them). Phonological cues were mildly facilitative (15 words were cued, resulting in 5 correct responses). Conclusions from Assessments: Semantic processing is relatively unimpaired at least for concrete words and pictures. Despite this, naming is virtually impossible. Although reading is also poor it is significantly better than naming. There is equal success on regular and irregular words, suggesting that GF is not just using GPC. It seems likely, therefore, that she reads aloud using VIL to POL. The reading results suggest that some phonological representations are retained. So the naming problem seems due to impaired access to the POL from semantics. Therapy Decisions: Therapy aimed to restore access to lexical phonologies. Therapy could recruit GF’s good monitoring skills to encourage reflection upon the phonological properties of words. Tasks also encouraged GF to make use of any partial phonological knowledge she might have about words, rather than simply providing her with cues. Thus we were aiming to develop a conscious, phonological self cueing strategy. Therapy comprised 40 sessions (each 20 minutes) conducted in GF’s own home. Therapy lasted 6 months. Therapy stimuli: a core group of 24 words featured in every session (these were the treated items tested before and after therapy). Plus 50 words were used in therapy, on a random basis. These words were used to expand the therapy set and to make sure that GF was not simply drilled on a small group of items. Tasks: 1. Syllable judgement GF heard a spoken word and had to judge whether it contained 1 or 2 syllables. At first the syllable structure was emphasised through exaggerated intonation. Then normal speech was used. Finally GF made the judgement purely from a picture of the item or from the real object (ie now she had to access the phonology herself). If she failed to make the judgement the therapist spoke the word for GF to judge. 2. Initial phoneme judgement GF heard a word and had to judge its first phoneme, first from a choice of 2, then from a choice of 6 (phonemes were presented as written letters on a card). Finally GF had to make the judgement from a picture of the item, or from the real object. If GF made an error the therapist pointed to and produced the correct first phoneme. 3. Judgement tasks with naming This level encouraged GF to use the accessed phonological information about a word as a self cue. As above, she was required first to judge the syllable structure and then the first phoneme of a word. Having accessed the phoneme she was encouraged to produce it as a cue for naming. If she could not, the therapist supplied the phoneme, which GF had to repeat and than attempt to name the item. This stage was the least successful. Often GF simply named the item after making her judgement, making the self cueing strategy redundant. If she did not name it, she found it very difficult to ‘translate’ her phonological knowledge into a cue, eg she could often not articulate the phoneme. Results of therapy (picture naming assessment) pre Treated words 6/24 Phonologically related controls 5/24 Phonologically unrelated controls 2/24 Total 13/72 post 18/24 14/24 12/24 44/72 follow up 16/24 12/24 10/24 38/72 pre 2 1/40 28/40 post 17/40 31/40 Other PALPA tests naming pictures matching written words to pictures (pre 1 = 6 months before the study) pre 1 0/40 There was a dramatic improvement in naming which seemed to generalise both to related words (starting with the same first phoneme as the treated set) and unrelated words. The generalisation to controls might suggest that the results simply reflect spontaneous recovery. However, this seems unlikely since GF’s naming prior to therapy was stable, and unrelated tasks, like written word to picture matching, were unchanged. As the self cueing component of therapy was least successful. We argued that GF had recovered ‘automatic’ and generalised access to the POL. A final point. After assessment we speculated that GF had impaired access to entries in the POL, rather than the loss of those entries. The fact that therapy gains generalised to untreated items supports this hypothesis (ie if entries had to be ‘reinstated’ there could have been no such generalisation). Conclusions: Hickin et al 2007: Gains in narrative and conversation depend on the person recovering some generalised access to word forms. Given that this generalisation is not always achieved, it is important to integrate naming therapy with a more global approach to the person’s difficulties. For example, the therapist might also work on compensatory strategies, such as gesture, drawing or a communication book. Therapy can also aim to change the behaviours of those in the aphasic person’s environment, so that communication can proceed despite the aphasia.