23 November 2012 - SALLE DU CONSEIL

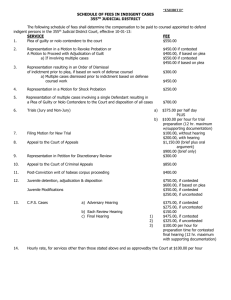

advertisement