Doctorate in Clinical Psychology Thesis Research Summary How do

advertisement

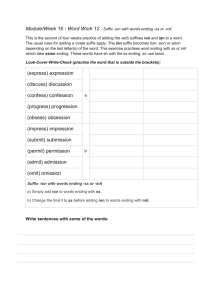

Doctorate in Clinical Psychology Thesis Research Summary How do clients experience ending in Cognitive Analytic Therapy? A qualitative analysis of what it means to end a time-limited therapy. Research team Peter Lydon, Trainee Clinical Psychologist, Lancaster University Doctorate in Clinical Psychology Dr. Ian Smith, Academic Supervisor, Lancaster University Doctorate in Clinical Psychology Dr. Claire Iveson, Field Supervisor, Merseycare NHS Trust Making the research possible The following study was only possible, and is gratefully indebted, to the nine people who were willing to discuss and share their experience of ending therapy (the ‘participants’). Similarly, a number of therapists and organisations offered significant help in publicising this study to individuals who might take part, and their help too is also hugely appreciated. Purpose of the research Ending therapy has been highlighted as an important but potentially complex stage of the therapeutic process for clients. The potential for feelings of loss, disappointment and abandonment have been discussed alongside the possibility of ending representing a time for pride and transformation. However, very little research has been conducted which explores the client’s perspective of ending therapy and the meanings which ending held. This research therefore sought to ask clients directly about how they experienced and made sense of their therapy ending. This research recruited only individuals who had received Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT), a form of time-limited therapy increasingly offered by the NHS which incorporates both psychodynamic and CBT principles. Carrying out the research Invitations and adverts were posted to publicise the study to a large number of potential participants. As a result, nine individuals (2 male, 7 female; ages 26-64) came forward to be interviewed about their experience of the end of their therapy. All participants had received between 12-26 generally weekly sessions of CAT for a variety of difficulties, e.g. depression and eating problems. All had had a planned ending, as opposed to having left therapy early or abruptly. The participants came from three cities in the United Kingdom, and had been seen by seven different CAT trained therapists across the sample. Interview transcripts were analysed using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), which allows the research team to listen to participants’ voices and also make interpretations based on their stories and accounts. Four themes were identified, as follows: Findings Theme 1: “It was like an achievement, and just really frightened at the same time”: Hope and fear in a happy ending Many participants about the significant fear and anxiety felt at the loss of therapy and the therapist. Participants voiced their fear about how they would deal with difficulties and problems, even life in general, without the support and care of their therapist. Most participants also worried that therapy’s gains, often significant, would be lost on ending, with meanings that therapy would come to represent a failed venture. Alongside anxiety, participants also commonly described a wish to end therapy ‘on a high’, where the focus in the closing stages of therapy was on the progress that had been made and reasons for hope. This gave an impression that participants had sometimes possibly not fully disclosed how anxious they had felt to the therapist, maybe to reassure their therapist that therapy had been successful Example quotes “There was a fear that I'm losing an ally here, somebody who's on my side, who's not going to be there any more, and I'm going to have to fight my own corner, what if I don't win? It was frightening.” “because it's too short, and sweet to be ingrained in to you… I was frightened coming away from it, thinking, 'what now? ” “...it's very scary, very scary…. my therapist was trying to drill in to me, 'look realise how big this has been…you've gone from this to this... that's a massive step in such a short time'. I don't think I got it at the time.” Theme 2: “The first time I felt I wasn't the centre of your world”: The sweet but sorrowful parting from a valued connection All participants talked proudly of having formed a special, affirming, trusting and rewarding bond with their therapist. Consequently, ending often meant a time of feeling a lot of gratitude to their therapist for their help towards achieving change and progress, as well as on a more personal level for making them feel genuinely cared for and valued. A number of the people who took part in the research valued being able to communicate these warm feelings to the therapist in a goodbye letter. In return, many also experienced great satisfaction on receiving encouragement and recognition from their therapist in the letter they received. However, the value of the relationships seemed to be linked to more difficult emotions often experienced alongside the pride and satisfaction. Ending could be experienced as a difficult and confusing process of stepping out and disentangling from the close therapeutic bond which had grown. Linked to this, participants here talked of feeling sadness, loss and even grief at the end of therapy, sometimes with a disappointment that there could not be an extended or on-going relationship or connection with the therapist. In a number of accounts, participants also discussed feelings of rejection, abandonment, confusion or anger associated with parting from the therapist. Here, individuals described a sense of knowing that therapy was going to end, but still on an emotional level registering these difficult feelings. Ending seemed sometimes to symbolise a shift in people seeing themselves no more as a valued and cared about person in the therapist’s eyes, but rather now a soon to be former and forgotten client. These could be upsetting thoughts for participants, and sometimes seemed to threaten to undermine the positive feelings held towards the therapy experience. Only one participant in this research discussed having talked about these feelings with their therapist, with this having been a very important part of that individual being able to make sense of those feeling. For others it seemed that these thoughts and feelings had not been shared. Example quotes “You talk to someone in such depth, and expose yourself in that way, and then that person is gone…I felt sad, and that there was an empty space I suppose where he was no longer filling” “ I said to (the therapist)… I wish we'd met in a different situation, we could have been friends then, but I suppose it was difficult, because it's 'Ok well I'm never going to see you again'...I was sad, it hurt a little bit, but at the same time what she did was a great thing for me.” “you do feel a little bit rejected, I did, like not part of it anymore…, and then you think 'Do they even care?…they're just fleeting thoughts, because obviously you're completely aware that it was therapy, you… blur the lines.” Theme 3 : “Therapy isn't an ending…it's the tools to give you a new beginning”: A mixture of changed relationships with problems after ending Ending therapy was often experienced by participants as an exciting opportunity to start to put in to practice new self-awareness and tools to tackle often long standing problems. Personal change and recovery was often framed by participants as on-going goal rather than something which could be achieved or finalised by the last therapy session. Towards change, some participants seemed to consciously and actively think about and employ lessons from therapy on a daily basis. These changed ways of thinking or acting often seemed on the surface fairly simple, for example avoiding becoming too busy and tired but also with profound impact. For others, recalling and applying what was learned from CAT seemed to be done more consciously at times of particular difficulty or crisis. Here some participants talked about trying to reconnect with ‘what would my therapist say to me?’ to help them cope with the stressful circumstance. However, a number of participants talked about how difficult they had found it to put in to practice the changes which they had begun to make in therapy. Without the weekly sessions and the therapist’s guidance and motivation, many individuals found it hard to keep the therapy and its lessons in mind. In some other accounts, participants’ on-going relationships with CAT on ending seemed to reflect more distancing from, even dismissal of the therapy. Here, individuals talked of quickly losing, hiding away, or forgetting about the materials and ideas which had been taken from therapy. This research wondered if feelings of abandonment or rejection on ending had at least in part contributed to individuals themselves then turning away from therapy after ending. Example quotes you are given, the ideas… to explain how you're feeling…but therapy isn't an ending, the letter isn't an ending, it's the tools to give you a new beginning “it's very easy to slip back after the therapy. It's very difficult to keep that focus… to do that by yourself… to try to keep on track, to try to move forward...very very difficult” “if there was somewhere I could go to practice it with other people…and to remind me of what I'd learned, I'd be quite confident to carry on, I think it'd give me more...ability to cope with my life” “I've never give her (the therapist) another thought, and I did find her useful, and I did enjoy the therapy sessions that we had together. I really felt as if I was getting something out of them... that therapy file needs to be dug out” Theme 4: “You're on borrowed time…so it would mean I don't waste time”: Gaining objective but feeling objectified in the time limited ending The time limited nature of CAT raised multiple meanings and emotions for participants. For most, the pre-defined number of sessions represented a source of focus, motivation and objective, seeming to spur individuals on to work to make the most of the therapy experience. It also seemed to help individuals to remember that time in therapy was finite, appearing to help participants to avoid a commonly perceived risk of coming to rely too heavily on the therapist. However, most accounts simultaneously reflected a strong sense of frustration at the lack of individual control and choice over timing of ending. A sense of therapy feeling rushed or pressured due to the imposed schedule was common in accounts. Some participants felt that their potential progress in therapy was cut short due to the imposed ending coming at a point while gains were still developing. Here, a sense of clients feeling objectified and not treated as individuals was apparent. This sense of pressure, as if being on a conveyor belt of clients, was often seen as related to the National Health Service (NHS) context of services. Example quotes “you're given a timeline… you know you're on borrowed time effectively, so … it would mean I don't waste time, I don't want to lie, so it does inform how you approach it.” “If you carried on even longer, which I felt it needed to be, there is one big danger…using it as a kind of prop...but without getting further forward.” “you're going to be talking about your childhood…and how it relates to now, it just isn't the time to get that out … it's just 'push, push, push, push, push' very very rushed” “I really don't think there should be an ending. I think the ending should come from the person who needs the therapy, rather than the powers that be that put the systems in place.” Conclusions and Implications This research has illuminated the potential gains, pitfalls, conflicting emotions and meanings which can be experienced in ending therapy. Implications included that conversations facilitated by therapists can be very helpful to help individuals to acknowledge and process possible difficult emotions related to ending therapy. While a pre-determined ending was described as introducing motivation and focus to engagement, participants’ responses suggested that negotiation and flexibility around how the ending was managed (e.g. spaced sessions towards ending) offered a greater sense of collaboration and individuation need. Endings were often discussed with reference to the process of change. Many participants considered achieving or maintaining personal change after ending therapy to be a difficult process, sometimes with a feeling that true change only began after therapy ended. The loss of the focus enjoyed during therapy was often discussed as making on-going change difficult. Groups of former CAT clients coming together to mutually support and maintain efforts towards change was suggested as one solution to make the process of change after ending more successful. Again, sincere thanks to all those who took part and helped in the recruitment process. Any correspondence can be addressed to Peter Lydon, c/o Clinical Psychology, Furness college, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YG or lancslydon@yahoo.co.uk