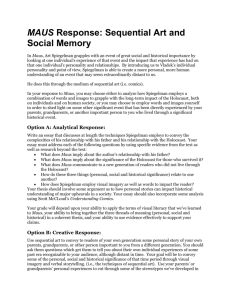

The Holocaust Experience in Maus Of Mice, Men, Cultural Violence

advertisement

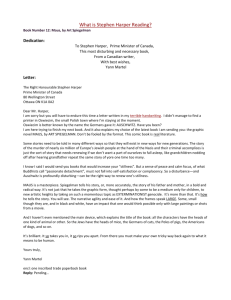

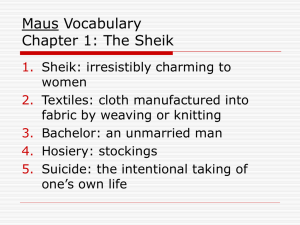

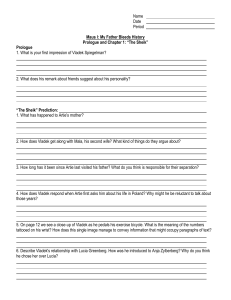

The Holocaust Experience in Maus: Of Mice, Men, Cultural Violence and Identity. “To die, it’s easy. But you have to struggle for life” - Art Spiegelman, Maus. Amongst the most crucial issues of the previous century, the discourses on violence: the definitions of enemies and victims; its effect on our conduct and the perceptions of war and genocide, seem to have redefined our ideas of identity and stereotype. Historians and contemporary writers have long sought to identify and lay bare the numerous connections between the German discourse on nationalism, Aryan identity and Nazism, and the Jewish discourse on identity and Holocaust, and how these two ideas, even though antithetical to each other, formed a complex reciprocal relationship which achieved an unfortunate apogee in concepts of Anti-Semitism, which produced psychologically pathological version of antiJudaism that gripped not only Hitler’s Germany, but almost the entire continent for years to come. Jewish-American literature created by writers such as Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Howard Jacobson and others show and record these struggles and their effects on contemporary Jewish thought and amidst this complex intellectual engagement, lies Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. (Brown, Michael, Studies in American Jewish Literature: Asserting Identity in a Post-Holocaust Age, 1993.) Joshua Brown, in his essay ‘Of Mice and Memory’, describes Maus as a ‘digest sized comic book using mice, cats, pigs, and other animals to portray a history of the Holocaust’. The use of coded animal identities for the ethnic and national groups, strikingly similar to that of Animal Farm by Orwell, often works at the level of cruel and obscene metaphor to demonstrate how the Jews were treated and how they reacted, like helpless rats who were hunted, hated and degraded to the lowest standards of living. The portrayal of Jews as Maus (the German word for mouse) also required Spiegelman to portray the Nazis as Cats. Since Nazis were being defeated and destroyed by the Americans in the Second World War, it automatically meant that Spiegelman would have to use the animal Dog for them. Maus is not a fictional comic strip, nor is it an illustrated novel: yet it is an important historical work that offers historians and oral historians in particular, a unique approach to narrative construction and interpretation. This text in two volumes, considers the lives and stories of some people who survived the Holocaust- as did the narrator Artie’s father Vladek; and some who did notincluding an older brother Richieu who died during the war; wand some who seem to have survived only provisionally, as his mother Anja, who killed herself much later. There is also a strong evidence of conflict over narrative control between the father and the son, often taking the form of hurtful and contentious struggle. Andreas Huyssen discusses whether this second generation Holocaust narrative risks aestheticizing violence and concludes that Maus’ multiple frames “draw the narrator as a witness to witness, as both a listener and carrier of the father’s testimony of violence”. Thus, Maus transcends beyond a story about the control of the narrative and becomes a text about how to hear the story of violence. The author essentially wrote himself into a family, whose trauma he did not face and hence, became implicated to in the future when he used the visual terrain to envision the graphic depiction of the Holocaust through Maus. The power of Maus derives from the evocative accent of his father’s words and the fact that Spiegelman is a rebel in selecting animal allegory to narrate his familial link to the Holocaust past. The most significant form of violence explored in Maus is probably that of ‘cultural violence’, apart from the killings and torture that fashioned the Holocaust experience. Cultural violence explores assaults against those aspects which are symbolic to our existence and exemplified by religion and ideology, language and art, empirical science and formal science. (Galtung, Johan; Cultural Violence, 1990.) This form of violence often justifies and legitimizes direct and/or structural violence, by deeming a certain culture subservient to another. However, it is important to note that culture itself can be violent, when used as a social construct or a monolith which is imposed upon people, thus preventing them from acting from a position of agency. One way cultural violence works, according to Galtung, is by changing the moral colour of an act from red (wrong) to green (right), or at least yellow (acceptable). The extermination of Jews, in many ways, became and was acceptable in the German civil society, despite later historians’ attempts of salvaging the German citizens by showing that they were unaware of the goingson of the concentration camps. These efforts connect to another way in which cultural violence functions: by making reality opaque. To some extent, the authenticity of these statements can be proven, as under Hitler’s regime there were special authorities who were put in charge of propaganda and kept the world convinced about the ‘happy life’ Jews led in the concentration camp. In Maus, the explicit use of framing; of competing narratives layering past and present, visual and verbal; and of cartoon stereotype: these all come together not only to produce a more open, ethical, history of cultural violence, but even further, to illuminate the very material dangers to particular people of narrating violence, of telling- and hearing- tales of orchestrated violence. (Mandaville, Alison; Comics Narrative, Gender, and the Father Tale in Art Spiegelman’s Maus, 2009.) With modernity, there emerged the concept of ‘Self’ and ‘Other’ under the archetype of Nationalism. Under Hitler’s ideology, a steep gradient was thus created: exalting the value of the ‘Self’- the blue eyed blonde haired male and dehumanizing the ‘Other’- the vermin or rat like Jews. This form of structural violence informs itself from prevalent cultural notions, and Spiegelman, in many instances of the book, utilizes the graphic advantage to bring forth the same. Although Maus focuses on Vladek’s story, Spiegelman succeeds, through succinct narration and dialogue, in keeping is aware of the changing social and political climate of Sosnowiec, and from there the larger context of Poland and the Third Reich. Feminists work on Holocaust memory has explored the gendered violence during those times. Anja and her missing story functions as one of the dominant tropes of Holocaust representation, which refocuses on the idea that Maus may just be a search for individual identity or cultural survival through the missing mother tale, or a similarly self reflexive journey through the suspect father’s tale. The carefully situated Jewish mother’s death serves here as a metaphor for the emergence in the Jewish community of a new understanding of “the Holocaust” in the late 1960s. Maus draws its literary power from this negativity. By choosing to grapple with Holocaust, despite the absence of his mother-and brotherSpiegelman create an analogy between the story of his family and the larger context that Maus is placed in: the enormous magnitude of lost human lives during these historical events. Violence consolidates itself the moment violent structures are institutionalized and the violent culture is internalized. It perpetuates itself in a repetitive, ritualistic manner, almost like a vendetta. Vladek continues to live his life much like he did when he was in the concentration camp and during the early days of the Nazi invasions when he would scrounge for sugar, food, clothes and other essentials for himself and others. The suffering endured by Vladek, as if the Nazi persecution never ended, depicts how structures of violence can continue to effect human psyche despite their apparent removal. The source of this continued punishment can be traced to ‘survivor’s guilt’, another outcome of structural violence wherein it renders the survivor guilty for outliving families and friend. Perhaps, Vladek sought to recreate his preHolocaust family- Anja and Richieu. Mala and Art, who have seemingly replaced them, are not enough. “I am tired of talking, Richieu”, he tells Art at the end. Borrowing from Hannah Arendt, who claimed that “the development of a Jewish culture, in other words, or the lack of it, will from now on not depend upon circumstances beyond the control of Jewish people, but upon their own will.”, indeed, Vladek decided to live with the identity imposed on him by the Holocaust, probably in the hope to bring his original family back to life, at least in his head. The ingenuity of Maus lies in the fact that, it may be a biography, but it is a comic strip biography. It is a tale of detection for the violence of narrative itself, for the stories and images- including those of nation and gender- that allow and even generate a holocaust. For as the comic form makes materially evident, these are stories and images that haunt narratives of survival, and so, through the material form of comics, they can be tangibly retraced through the survivor’s tale. Bibliography: Spiegelman, Art; Maus I & Maus II Spiegelman, Art & Rothberg, Michael, “We were talking Jewish”: Art Spiegelman’s Maus as a Holocaust Production, 1994. Loewenstein, Andrea F.; Confronting Stereotypes: Maus in Crown Heights, 1998. Mandaville, Alison; Comics Narrative, Gender, and the Father Tale in Art Spiegelman’s Maus, 2009. Brown, Michael, Studies in American Jewish Literature: Asserting Identity in a PostHolocaust Age, 1993. Arendt, Hannah. The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age, 1978. Brown, Joshua; Of Mice and Memory, 1988. Galtung, Johan; Cultural Violence, 1990. Foley, Barbara; Fact, Fiction, Fascism: Testimony and Mimesis in Holocaust Narratives, 1982. Beller, Steven; A Very Short Introduction to Anti-Semitism, Oxford.