New Deal Placards

advertisement

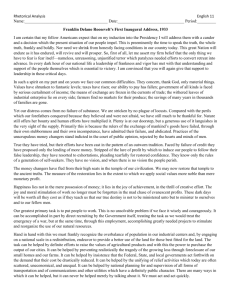

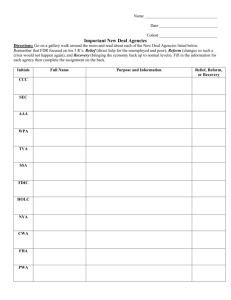

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC): The CCC was part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, and was designed to provide jobs for thousands of unemployed young men to work towards conservation on a national scale. When President Roosevelt took office in 1933 he faced a nation that was bankrupt in money and spirit. One of his first acts was to ask Congress for a large appropriation for emergency conservation work. This resulted in the passage, in March 1933, of the Emergency Work Act, or as it came to be called the "Civilian Conservation Corps." It was a program to recruit thousands of young men to work in forests, parks, lands and water in the preservation and use of basic natural resources. Men between the ages of 17 and 25 who were unmarried, out of school and unemployed were eligible for enrollment. They were paid $30.00 a month, $25 of which was sent home to their families or if they had no family, it was held in an account for the enrollee until they were discharged from the camp. The boost to the economy brought by these checks was felt throughout the country. There was a social impact. These young men were taken off the streets. They traveled far from home and performed useful work in a healthy environment. Over 110,000 illiterates learned to read and write. The men worked 40-hour, six-day weeks, in crews of 48. Each crew had a leader and assistant leader who were in charge in the barracks and on the job. “Bank Holiday” When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, one in four Americans was out of work nationally, but in some cities and some industries unemployment was well over 50 percent. Equally troubling were the bank panics. Between 1929 and 1931, 4,000 banks closed for good; by 1933 the number rose to more than 9,000, with $2.5 billion in lost deposits. Banks never have as much in their vaults as people have deposited, and if all depositors claim their money at once, the bank is ruined. Millions of Americans lost their money because they arrived at the bank too late to withdraw their savings. The panics raised troubling questions about credit, value, and the nature of capitalism itself. And they made clear the unpredictable relationship between public perception and general financial health—the extent to which the economy seemed to work as long as everyone believed that it would. To stop the run on banks, many states simply closed their banks the day before Roosevelt’s inauguration. Roosevelt himself declared a four-day “bank holiday” almost immediately upon taking office and made a national radio address on Sunday, March 12, 1933, to explain the banking problem. This excerpt from Roosevelt’s first “fireside chat” demonstrated the new president’s remarkable capacity to project his personal warmth and charm into the nation’s living rooms. Just days after taking office, FDR declared a national “banking holiday”. Only banks that were declared solvent by the government were allowed to reopen. The bank holiday aimed to restore faith in the nation’s banking industry. President Roosevelt’s First Fireside Chat (March 12, 1933) …First of all, let me state the simple fact that when you deposit money in a bank, the bank does not put the money into a safe deposit vault. It invests your money in many different forms of credit -- in bonds, in commercial paper, in mortgages and in many other kinds of loans. In other words, the bank puts your money to work to keep the wheels of industry and of agriculture turning around. A comparatively small part of the money that you put into the bank is kept in currency -- an amount which in normal times is wholly sufficient to cover the cash needs of the average citizen. In other words, the total amount of all the currency in the country is only a comparatively small proportion of the total deposits in all the banks of the country… Glass-Steagall Act: In June of 1933, The Banking Act brought significant reform to banking: it separated commercial from investment banking it increased the authority of the Federal Reserve to prevent member banks from engaging in excessive speculation it created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to federally guarantee deposits up to $2,500 Federal Emergency Relief Association (FERA) 1933: The economic collapse of 1929 known as the Great Depression caused widespread hardship throughout the United States. When President Franklin Roosevelt took office in January 1933, 15 million Americans were unemployed. Many had lost not only their jobs, but their also their savings and homes and were dependent on relief money from the government to survive. Businesses and banks had closed, production and sales of goods and services had been severely reduced. Most federal relief efforts had been mired for some time in a quagmire of political and legislative wrangling. Little aid or direction had actually reached the state level. "When Roosevelt appointed Hopkins as director of FERA, he called him to his office for a five-minute talk. The president told the Washington newcomer two things: give immediate and adequate relief to the unemployed, and pay no attention to politics or politicians. Hopkins did just that. Thirty minutes later, seated at a makeshift desk in a hallway . he began a program committed to action rather than debate, a program that would eventually put 15 million people to work. Even more important, FERA established the doctrine that adequate public relief was a right that citizens in need could expect to received from their government." (J. Hopkins p. 309) FERA had three primary objectives: 1) Adequacy of relief measures; 2) providing work for employable people on the relief rolls; and 3) diversification of relief programs. FERA accepted as elementary that all needy persons and their dependents should receive sufficient relief to prevent physical suffering and to maintain a minimum standard of living." (Williams p. 96) In a report to Congress in 1936, FERA indicated that while actual physical suffering was prevented, it was never fully possible to achieve living standards of minimum decency for the entire population in need of relief. Public Works Administration (PWA): Created by the National Industrial Recovery Act on June 16, 1933, the Public Works Administration (PWA) budgeted several billion dollars to be spent on the construction of public works as a means of providing employment, stabilizing purchasing power, improving public welfare, and contributing to a revival of American industry. Simply put, it was designed to spend "big bucks on big projects." More than any other New Deal program, the PWA epitomized the Rooseveltian notion of "priming the pump" to encourage economic growth. Between July 1933 and March 1939, the PWA funded the construction of more than 34,000 projects, including airports, electricity-generating dams, and aircraft carriers; and seventy percent of the new schools and one third of the hospitals built during that time The PWA spent over $6 billion, but did not succeed in returning the level of industrial activity to predepression levels. Nor did it significantly reduce the unemployment level or help jump-start a widespread creation of small businesses. FDR, personally opposed to deficit spending, refused to spend the sums necessary to accomplish these goals. Nonetheless, the historical legacy of the PWA is perhaps as important as its practical accomplishments at the time. It provided the federal government with its first systematic network for the distribution of funds to localities, ensured that conservation would remain an element in the national discussion, and provided federal administrators with a broad amount of badly needed experience in public policy planning. When FDR moved industry toward war production and abandoned his opposition to deficit spending, the PWA became irrelevant and was abolished in June 1941. Farm Credit Association (FCA): Homeowner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC): The Farm Credit Act of 1933 provides for organizations within the Farm Credit Administration. The Farm Credit Act of 1933 was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, to help farmers refinance mortgages over a longer time at below-market interest rates at regional and national banks. This helped farmers recover from the Dustbowl. The Emergency Farm Mortgage Act loaned funds to farmers in danger of losing their properties. The campaign refinanced 20% of farmer's mortgages. Continued high unemployment is unfortunately not the only bad piece of economic news that the nation has had to face this summer. It now appears as if the level of home foreclosures will continue at an alarming pace, with many economists now predicting that the number of Americans likely to lose their homes in 2010 will exceed one million — a figure that would surpass the more than 900,000 homes lost to foreclosure in 2009. With so many homes at risk, the current housing crisis certainly rivals that which struck the nation in the wake of the 1929 crash, when the housing industry all but collapsed. Indeed by the end of 1933, housing starts had fallen to one tenth of pre-1929 levels, and the number of urban homes that were either in delinquency or in foreclosure was running at a staggering fifty per cent. The New Deal response to this crisis was immediate and effective. In June of 1933, FDR signed the Homeowners Refinancing Act, which established the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), a new federal agency whose chief purpose was to refinance existing home mortgages that were in default and at risk of foreclosure. The HOLC also assisted mortgage lenders by providing them with additional capital and by refinancing problematic loans. By the close of 1935, when the program had come to an end, the HOLC had refinanced approximately twenty per cent of all the urban mortgages in the United States — over one million homes — and had lent out roughly $3.5 billon (an estimated $750 billion in today’s dolla rs). Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) 1933: The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was a United States federal law of the New Deal era which reduced agricultural production by paying farmers subsidies not to plant on part of their land and to kill off excess livestock. Its purpose was to reduce crop surplus and therefore effectively raise the value of crops. The money for these subsidies was generated through an exclusive tax on companies which processed farm products. The Act created a new agency, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to oversee the distribution of the subsidies. "The goal of the Agricultural Adjustment Act, restoring farm purchasing power of agricultural commodities or the fair exchange value of a commodity based upon price relative to the prewar 1909-14 level, was to be accomplished through a number of methods. These included the authorization by by the Secretary of Agriculture to secure voluntary reduction of the acreage in basic crops through agreements with producers and use of direct payments for participation in acreage control programs; to regulate marketing through voluntary agreements with processors, associations or producers, and other handlers of agricultural commodities or products; to license processors, association, and others handling agricultural commodities to eliminate unfair practices or charges; to determine the necessity for and the rate or processing taxes; and to use the proceeds of taxes and appropriate funds for the cost of adjustment operations, for the expansion of markets, and for the removal or agricultural surpluses." On January 6, 1936, the Supreme Court decided in United States v. Butler that the act was unconstitutional for levying this tax on the processors only to have it paid back to the farmers. Regulation of agriculture was deemed a state power. As such, the federal government could not force states to adopt the Agricultural Adjustment Act due to lack of jurisdiction. However, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 remedied these technical issues and the farm program continued. National Youth Administration (NYA): The National Youth Administration (NYA) was launched by executive order in June of 1935. Its goals were two-fold. The first was to prevent young people already enrolled in high school and college from dropping out due to financial hardship. This was accomplished by providing the students with grants in return for part-time work in libraries, cafeterias, as janitors, etc., with the twin objectives of developing the talents of young people while at same time keeping them out of the struggling labor market. The second goal was to provide training and/or employment of long-term value. By 1937, more than 400,000 youth were either employed or in job training programs under the auspices of local NYA offices. With the outbreak of the war in Europe in 1939 these figures increased significantly, with the vast majority of those in the program getting training as skilled machinists to work in the nation’s burgeoning defense industries. The productive labor of these NYA-trained workers helped turn the United States into the great “Arsenal of Democracy” that made it possible for us to win the war against fascism. Moreover, under the leadership of such enlightened figures as Aubrey Williams, the NYA also worked to specially address the problems of unemployment and access to education among African Americans. Williams created an Office of Minority Affairs headed by Mary McLeod Bethune, who would soon become one of the most effective and outspoken advocates for the employment and educational rights of blacks in the country. Overall, the NYA helped over 4.5 million young people find work, get vocational training, or afford a better education before the office was closed down in 1943. Equally important, it helped a struggling generation not only to maintain its dignity, but also to contribute to the growth and productivity of the American economy at a desperate time in our history. Indeed, even though the NYA was a federal program, it became enormously popular among the business community and offers us a fine example of what enlightened leadership can do in a moment of great crisis. Surely providing jobs and making education and vocational training more affordable for young people is an investment in our future that this generation of Americans — and all generations — deserve. With youth unemployment approaching 25 percent, and with the cost of higher education skyrocketing, perhaps it is time to offer this generation the hope and promise of another NYA. Security and Exchange Commission (SEC): The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is a federal agency that provides protection for investors and regulates the bulk of the securities industry - including U.S. stock exchanges, options markets, and other electronic exchanges and securities markets. It was created by The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 -- a law governing the secondary trading of securities in the U.S. The commission's division of enforcement investigates possible violations of federal securities-related laws and can take civil action with other law enforcement agencies when it comes to criminal cases. The stock market crash of 1929 The market crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression took a toll on the public's trust in capital markets. Investors looking to go from rags to riches turned to the stock market during the roaring 20s. According to the SEC , an estimated $50 billion in new securities were offered, and half became worthless. The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Thus, Congress passed The Securities Act of 1933 and The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (which created the SEC) in an effort to restore confidence in the markets. Publicly-traded companies were now obligated to disclose investment risks and provide full information about the state of their business. Brokers, dealers and exchanges were now legally required to put the interests of the investors first and treat them in a fair and honest manner. Congress established the SEC to enforce these laws for the sake of the investors and the future of market stability. Wagner Act: National Labor Relations Board (NLRB): The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), also known as the Wagner Act, passed through Congress in the summer of 1935 and became one of the most important legacies of the New Deal. Reversing years of federal opposition to organized labor, the statute guaranteed the right of employees to organize, form unions, and bargain collectively with their employers. It assured that workers would have a choice on whether to belong to a union or not, and promoted collective bargaining as the major way to insure peaceful industry-labor relations. The act also created a new National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to arbitrate deadlocked labor-management disputes, guarantee democratic union elections, and penalize unfair labor practices by employers. The law applied to all employers involved in interstate commerce other than airlines, railroads, agriculture, and government. The act contributed to a dramatic surge in union membership and made labor a force to be reckoned with both politically and economically. Women benefitted from this shift as well, and, by the end of the 1930s, 800,000 women belonged to unions, a threefold increase over 1929. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA): President Franklin Roosevelt needed innovative solutions if the New Deal was to lift the nation out of the depths of the Great Depression, and TVA was one of his most innovative ideas. Roosevelt envisioned TVA as a totally different kind of agency. He asked Congress to create “a corporation clothed with the power of government but possessed of the flexibility and initiative of a private enterprise.” On May 18, 1933, Congress passed the TVA Act. From the start, TVA established a unique problem-solving approach to fulfilling its mission: integrated resource management. Each issue TVA faced — whether it was power production, navigation, flood control, malaria prevention, reforestation, or erosion control — was studied in its broadest context. TVA weighed each issue in relation to the whole picture. From this beginning, TVA has held fast to its strategy of integrated solutions, even as the issues changed over the years. Even by Depression standards, the Tennessee Valley was in sad shape in 1933. Much of the land had been farmed too hard for too long, eroding and depleting the soil. Crop yields had fallen along with farm incomes. The best timber had been cut. TVA built dams to harness the region’s rivers. The dams controlled floods, improved navigation and generated electricity. TVA developed fertilizers, taught farmers how to improve crop yields and helped replant forests, control forest fires, and improve habitat for wildlife and fish. The most dramatic change in Valley life came from the electricity generated by TVA dams. Electric lights and modern appliances made life easier and farms more productive. Electricity also drew industries into the region, providing desperately needed jobs. The Social Security Act (1935): On August 14, 1935, Franklin Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act. During the Great Depression many older people were unemployed. Americans were living longer but retiring earlier; age discrimination made it difficult for elderly Americans to find employment. People who had worked hard all their life to support their families were living in poverty. Americans all over the country argued that they deserved compensation. Dr. Francis E. Townsend advocated that all Americans over the age of 60 should stop working and receive $200 per month from the federal government, and he gathered over 5 million supporters. As "Townsend Clubs" sprang up across the country, Franklin Roosevelt knew he had to do something to address the plight of unemployed, older Americans. As Governor of New York State FDR enacted a law to provide old-age pensions and was ready to extend it nationally. By Executive Order, Roosevelt created the Committee on Economic Security and their recommendations provided the basis for Congress' 1935 Social Security Act. Under the Act, Congress appropriated some funds for the program, but the rest of the money came from a payroll tax. Money was taken out of an employee's paycheck to help pay for Social Security, which in 1937 was about 2% of each paycheck. Older Americans, and later dependents and the disabled were given the money. Initially 60% of the workforce was covered by Social Security (by 1995, 95% of the workforce was covered). Ernest Ackerman was the first person to receive Social Security; he retired one day after the program began. For that one day the government withheld $.05 of his paycheck but later he got back a lump-sum payment of $.17. During the first few years of Social Security, eligible Americans received, on average, $58.06. Before Franklin Roosevelt's administration, it was unusual for the government to give people money, and some Americans were against Social Security. In two cases, the Supreme Court ruled on the Constitutionality of the Social Security Act, but ruled in both instances that Congress could legislate on this national issue. Social Security is one of the many things still in place today because of Franklin Roosevelt. Americans still pay into Social Security while they work so that they will receive money when they stop working. The National Labor Relations Act (1935): THE WAGNER ACT At the beginning of the New Deal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his Labor Secretary, Frances Perkins, steered a progressive middle course in labor relations. They and many of their advisers believed that if laws and regulations could be put in place that improved workplace conditions and increased wages, then workers would not need unions. This idea was a guiding principle in the National Industrial Recovery Act that sought to bring management, labor, and consumers together to create industrial codes that produced goods at a fair price, under fair working conditions, and resulted in a fair profit. But although the NIRA included a provision known as Section 7a that guaranteed workers the right of collective bargaining, factory owners regularly broke strikes or set up alternate “company unions” that they asserted satisfied the requirements of Section 7a. In an effort to resolve the growing labor crisis, a National Labor Relations Board was established in 1934, but it was administratively weak and had little enforcement power. When the NIRA was finally struck down by the Supreme Court in May 1935 based on the unconstitutionality of the industrial codes, only the weak Section 7a remained. Enter United States Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York. Wagner was a German immigrant who had come to the United States at the age of nine, he attended the New York City public schools, worked his way through college and law school, and became active in local Democratic politics. Wagner deeply believed in the New Deal’s goal to provide economic security to lower-income groups. He was an early supporter of public housing, public works programs, unemployment insurance, and the Social Security Act. As historian Anthony Badger has noted, “running through all Wagner’s thinking was not just concern for social justice but also a conviction that the American economy could not operate at its fullest capacity unless mass purchasing power was guaranteed by government spending, welfare benefits, and the protection of workers’ rights.” And so Wagner took up the cause to improve upon the foundation laid by Section 7a of the NIRA. The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 is the product of his efforts, and as a result, it is the law most closely associated with his name. The Wagner Act not only restated the Section 7a right of workers to collective bargaining, it established a new independent National Labor Relations Board with real enforcement powers to protect this right. Under the new law, employee union elections were certified by the NLRB and were based on majority rule and exclusive representation. The so-called “company unions” previously used by management to flout collective bargaining rights were outlawed, as were other unfair labor practice such as blacklisting, strike-breaking, and discriminatory firings. The NLR B was empowered to hold hearings and compel compliance by management. Because of the Wagner Act, union membership increased dramatically throughout the 1930s, and by 1940 there were nearly 9 million union members in the United States. The system of orderly industrial relations that the Wagner Act helped to create led to an era of unprecedented productivity, improved working conditions, and increased wages and benefits. Today, the Wagner Act stands as a testament to the reform efforts of the New Deal and to the tenacity of Senator Robert Wagner in guiding the bill through Congress so that it could be signed into law by President Roosevelt. Works Progress Administration (WPA): The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was a relief measure established in 1935 by executive order as the Works Progress Administration, and was redesigned in 1939 when it was transferred to the Federal Works Agency. Headed by Harry L. Hopkins and supplied with an initial congressional appropriation of $4,880,000,000, it offered work to the unemployed on an unprecedented scale by spending money on a wide variety of programs, including highways and building construction, slum clearance, reforestation, and rural rehabilitation. So gigantic an undertaking was inevitably attended by confusion, waste, and political favoritism, yet the 'pump-priming' effect stimulated private business during the depression years and inaugurated reforms that states had been unable to subsidize. Particularly novel were the special programs. The Federal Writers' Project prepared state and regional guide books, organized archives, indexed newspapers, and conducted useful sociological and historical investigations. The Federal Arts Project gave unemployed artists the opportunity to decorate hundreds of post offices, schools, and other public buildings with murals, canvases, and sculptures; musicians organized symphony orchestras and community singing. The Federal Theatre Project experimented with untried modes, and scores of stock companies toured the country with repertories of old and new plays, thus bringing drama to communities where it had been known only through the radio. By March, 1936, the WPA rolls had reached a total of more than 3,400,000 persons; after initial cuts in June 1939, it averaged 2,300,000 monthly; and by June 30, 1943, when it was officially terminated, the WPA had employed more than 8,500,000 different persons on 1,410,000 individual projects, and had spent about $11 billion. During its 8-year history, the WPA built 651,087 miles of highways, roads, and streets; and constructed, repaired, or improved 124,031 bridges, 125,110 public buildings, 8,192 parks, and 853 airport landing fields. WPA Posters & Art: National Industrial Recovery Act, U.S. labor legislation (1933) that was one of several measures passed by Congress and supported by Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt in an effort to help the nation recover from the Great Depression. The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was an unusual experiment in U.S. history, as it suspended antitrust laws and supported an alliance of industries. Under the NIRA, companies were required to write industrywide codes of fair competition that effectively fixed wages and prices, established production quotas, and placed restrictions on the entry of other companies into the alliances. These codes were a form of industry self-regulation and represented an attempt to regulate and plan the entire economy to promote stable growth and prevent another depression. Employees were given the right to organize unions and could not be required, as a condition of employment, to join or to refrain from joining a labour organization. Prior to this act, the courts had upheld the right of employers to go to great lengths to prevent the formation of unions. Companies could fire workers for joining unions, force them to sign a pledge not to join a union as a condition of employment, require them to belong to company unions, and spy on them to stop unionism before it got started. The law created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to promote compliance. The NRA was chiefly engaged in drawing up industrial codes for companies to adopt and was empowered to make voluntary agreements with companies regarding hours of work, rates of pay, and prices to charge for their products. More than 500 such codes were adopted by various industries, and companies that voluntarily complied could display a Blue Eagle emblem in their facilities, signifying NRA participation. The NIRA was declared unconstitutional in May 1935 when the Supreme Courtissued its unanimous decision in the case Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States. The court ruled that the NIRA assigned lawmaking powers to the NRA in violation of the Constitution’s allocation of such powers to Congress. Many of the labor provisions in the NIRA, however, were reenacted in later legislation.