Just shoot me article

advertisement

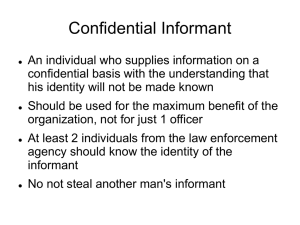

Just shoot me Author: Leonie Lamont Publication: Sydney Morning Herald Date: 05/02/2005 Section: News and Features Words: 1566 Page: 27 Source: SMH The two lives of an undercover policeman blurred into one wretched existence. Leonie Lamont reports. 'THE truly frightening thing is my life did not have to turn out like this. The NSW Police Service did not have to do much to leave me with some quality of life. As it is, I have none." So writes Andrew Curran. Cast back 15 years, and a 22-year-old from the bush joins the NSW police. Cast back 10 years when Curran has gone into undercover work. Picture his wife, a consultant, trying to ignore her colleagues' disdain at her low-life husband. His mother is embarrassed to walk down the street with him. Staff at his children's kindergarten wonder about this ratty-looking man picking up the kids. Cast back five years, and police driving on a late night patrol find Curran sitting in a gutter. When they inquire if they can help, he asks them to shoot him, and relieve his suffering. Look back three years and see him medically discharged, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, and picture the shattered family going into witness protection. This week, Curran folded his four-year-long negligence claim against the NSW Police Service, unable to cope with the eight-week trial ahead of him. The court entered a verdict for the police, but in documents prepared for his court case, Curran sheds light on the grim world of covert police work. Curran had been a uniformed policeman for six years before getting a taste for undercover work via a special operations group targeting drugs in Kings Cross in 1995. "It was exciting and rewarding ... I developed an intense hatred of drug dealers, seeing young teenagers prostitute themselves ... it was soul destroying," he wrote. Through his protected country upbringing he had not been exposed to drugs and had never taken them. But during an early operation a criminal under investigation handed him a bong. As the man left the room, his undercover partner frantically eyeballed him to smoke the stuff. Curran put the bong to his lips and sucked - but nothing happened. "The operative was whispering 'shotgun, shotgun'. I didn't know what he was on about." He didn't know he had to plug a small draft hole with his finger. It was new territory, not just for him but for his family. "I went from like I look now, fairly clean-cut, to looking like a junkie. My wife had to tell people she met whatever my covert name was at the time, and whatever my covert occupation was. "My wife worked for a consulting firm ... and you've got this absolutely ratty looking bloke coming up saying, 'Hi, I'm her husband'. The pressure on her was enormous," he told the Herald this week. When Curran applied for the undercover course, the couple had no appreciation of how engulfing the work would turn out to be. "During the course, a major component related to alcohol consumption. We were required to drink a lot of alcohol, most days to about 2 or 3am, so our performance while tired, intoxicated or hungover could be monitored," Curran wrote. Alcohol was to prove a mainstay, and by 1998, undercover in a murder investigation, he wrote that he spent most of his time drunk to cope with his fear: "1998 was the first time I realised I was a mess ... I was hyper-vigilant, intense anger, intense depression to the point that I locked my firearm at work because I was afraid I would use it on myself ... I was drinking very, very heavily. I couldn't do undercover operations unless I was drunk. "I didn't know who I was any more. I didn't know if I was a cop or a crook. "Combine the marijuana smoking with the enormous intake of alcohol, and I was spending large parts of my working life bombed out of my brain. I would be driving crooks around town or driving to score drugs and I would be so smashed I didn't know if I was Arthur or Martha. "This [drug taking] was another aspect that was accepted by supervisors and another area where I had to do it - but if I got caught I was on my own. "There is no way an operative can avoid drug usage, no way. The service knows this and they turn a blind eye." It's been years since Curran pumped up AC/DC in his car on the way to undercover meetings "to get the adrenaline going and to stem the fear". Afterwards he'd play Pachelbel's Canon. These days, he pretends not to be at home if anyone knocks on the door. Feeling threatened in public places, he hates shopping centres and is wary of people walking towards him, or behind him. "I have a very real alcohol problem; my temper can snap at the slightest reason. A crowded atmosphere at the supermarket is too much," he writes. "I cannot handle crowds or strangers, where I can't have a wall behind my back. I don't sleep any more." It has taken him years, he said, to try to find the person he used to be. His time undercover wreaked havoc on his moral values, and personality. "When I started in undercover work I hated drug dealers, hated drugs. By the time I left I seriously viewed drug dealers as people who were just supplying a service, and those who chose to use, used them at their own peril. Your outlook on life completely changes. It has taken me a long time to get back to where I was, the person I was, before 1995." He is not alone among undercover police who have emerged with their lives destroyed and serious drug and alcohol problems. He says most marriages end in divorce, and only knows of himself and one other undercover colleague whose marriages, though strained, have endured. His sense of betrayal, and a backdrop of the police service's insouciance towards its covert officers, are evident throughout his court affidavit. During his early days, working undercover for one of the metropolitan regional crime squads, "one thing was painfully obvious ... this was undercover work on the cheap", he wrote. He felt continually exposed. "The attitude of the hierarchy was that we were only doing low to mid-level drug deals, so we did not need covert premises ... the department didn't [want] to spend $250 a week for covert premises." In later years, he wrote, there were feelings of being betrayed by police Internal Affairs. "There was a 1998 warning from IA: 'Warn your operatives to be careful.' [But they] refused to elaborate. Was IA investigating one of the operatives? Had the operative been given up, did a group of criminals know ... where one of our homes were? IA refused to give further information. The stress levels in the office went through the roof. "It turned out that Internal Affairs knew that two corrupt officers had told a major drug dealer that one of their number was an undercover. "IA knew that operative was burnt three weeks prior to this meeting, and they were prepared to expose him to mortal danger in order to protect their investigation ... for months I was going to jobs wondering if I had been given up ..." Friendships with former colleagues were discouraged, and there was no form of debriefing, he wrote. "Very rarely did we go and have a few beers and discuss the job. We were never encouraged to talk about how we felt. It was just the culture. You were an operative and were expected to cope. If I couldn't cope, I could leave. These were highly professional and motivated detectives. The aspects of the damage stress can do were absolutely foreign to them. They were not trained to recognise or deal with the stress I had to deal with ... I do not know how many times I was told, 'If you don't like it, there are 500 people out there who want your job'. "We were supposed to receive psychological assessment and counselling every six months. I did not receive any counselling at all. The only time I saw a psychologist was in 1995 when I applied for the course for undercover, and in 1997 when Iapplied for undercover branch. "You handled the stress or you were sacked. It was simple. " Against his psychologist's advice, he works full-time in an industry far removed from police and security work. He is no longer under witness protection. There are good days, and bad. "Alcohol [still] controls me, I don't control it. It's a battle I fight on a daily basis. I'm getting better at it but I don't always win, " he said this week. "I have five stitches on this hand, from a couple of months ago. It was the first party we have had at our house for a decade, and I got drunk and lost the plot ... smashing bottles ... and that's one of the things with [post-traumatic stress disorder], there are these really irrational flashes of uncontrollable rage ... It's very difficult for everyone around you who cares about you."