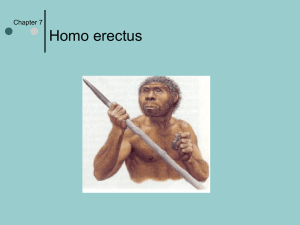

Homo Erectus

advertisement

Homo Erectus By 1.8 million years ago, some of the early transitional humans had evolved into a new, fully human species in Africa. Most paleoanthropologists refer to them as Homo erectus (literally "upright human"). However, a few researchers split them into two species--Homo ergaster (literally "working human") and Homo erectus. The ergaster fossils were presumably somewhat earlier and have been found for the most part in Africa. The erectus discoveries have been found widespread in Africa, Asia, and Europe. In this tutorial, ergaster and erectus will be considered one species--Homo erectus. Homo erectus were very successful in creating cultural technologies that allowed them to adapt to new environmental opportunities. They were true pioneers in developing human culture and in moving out of Africa to populate tropical and subtropical zones elsewhere in the Old World. This territorial expansion most likely began around 1.8-1.7 million years ago, coinciding with progressively cooler global temperatures. Surprisingly, however, Homo erectus remained little changed anatomically until about 800,000-700,000 years ago. After that time, there apparently were evolutionary developments in features of the head that would become characteristic of modern humans. By half a million years ago, some Homo erectus were able to move into the seasonally cold temperate zones of Asia and Europe. This migration was made possible by greater intelligence and new cultural technologies, probably including better hunting skills and the ability to create fire. The Homo erectus skeletal evidence at the "Peking Man" site of Zhoukoudian is especially important because it is from a population of men, women, and children rather than just a single individual. There was considerable sexual dimorphism and individual variability. The human remains were associated with large quantities of animal bones that apparently were mostly food refuse, though many of them had been chewed by large carnivores. A few of the bones had been burned in a way that suggests cooking. In addition, more than 100,000 stone, bone, antler, and horn tools were excavated. The cave was intermittently occupied by late Homo erectus for around 300,000 years, beginning around 750,000 years ago. In 1960, Louis and Mary Leakey found a 1.25 million year old Homo erectus partial cranium at Olduvai Gorge. Subsequently, more Homo erectus fossils were discovered there and at other sites in East, South, and Northwest Africa. The oldest known Homo erectus date to nearly 2 million years ago in East Africa. This strongly suggests that Homo erectus originated there. In 1984, Richard Leakey's team working at Nariokotome on the western side of Lake Turkana found a nearly complete Homo erectus skeleton of a 12 year old boy dating to 1.6 million years ago. It was named the "Turkana Boy." Three surprisingly early Homo erectus skulls were found during the 1990's on the fringes of Eastern Europe at Dmanisi in the Republic of Georgia. They date to 1.75 million years ago and look very much like the earliest Homo erectus from Africa--i.e., those that have been classified by some researchers as Homo ergaster. This discovery lends credence to the 1.8 and 1.6 million year old dates for Homo erectus from Java and to an early rather than late Homo erectus expansion out of Africa. Homo erectus-like bones were also discovered during the 1990's from several other sites in Western Europe and Africa that date 800,000-400,000 years ago. This partly reflects the fact that the picture of human evolution looks somewhat dissimilar in different regions of the World. It is now becoming clear that our evolution was not as straight forward as it once was commonly thought. Humans in some areas lagged behind. Anatomy Below the neck, Homo erectus were anatomically much like modern humans. Their arm and leg bones were essentially the same as modern people in shape and relative proportions. This strongly supports the view that they were equal to us in their ability to walk and run bipedally. However, their leg bones were apparently denser than ours. This may be partly a result of developmental adjustment differences. Unlike us, these early humans did not spend much of their lives sitting behind desks or on a sofa watching TV. They were probably much more active throughout the day seeking food. Their legs would have made Homo erectus efficient long distance runners like modern humans. It has been suggested that this capability would have allowed them to run down small and even medium size game animals on the savannas of Africa. If this was the case, it is also likely that they were largely hairless by this time. Bodies with little hair are more efficient at remaining cool via the evaporation of sweat during times of heavy exertion. Most other mammals primarily cool their bodies by panting. Because panting is less able to keep running animals from over heating, human hunters have a decisive advantage when chasing them over long distances. It also has been suggested that the pelvis in early Homo erectus may have been a bit narrower than in modern humans, which would require the infant brain to be smaller at birth and to then undergo considerable growth in childhood. However, we must be careful to not make too much of these differences because the number of existing specimens is low and there were minor regional variations as well. This becomes apparent especially when comparing Homo erectus from Asia and Africa. With the evolution of Homo erectus, there was a significant increase in body size compared to earlier hominids. Past estimates of Homo erectus stature frequently were in the 5-5½ feet (1.5-1.7 m.) range for adult males and around 100-110 pounds (45-50 kg.). The discovery of the "Turkana Boy" in 1984 brought this into question. This is not only the most complete specimen of this species so far discovered, but it is one of the earliest. The boy was only about 8-12 years old when he died but already 5 feet 3 inches (1.6 m.) tall. If he had lived to adulthood, he very likely would have grown to 6 feet (1.8 m.). As the number of nearly complete Homo erectus skeletons increases in the future, a clearer understanding of the range of their stature and body shape will likely emerge. Homo erectus heads were strikingly different from ours in shape. They had relatively strong muscles on the back of their necks. Their foreheads were shallow, sloping back from very prominent bony brow ridges (i.e., supraorbital tori ). Compared to modern humans, the Homo erectus brain case was more elongated from front to back and less spherical. As a consequence, the frontal and temporal lobes of their brains were narrower, suggesting that they would have had somewhat lower mental ability.