vinfo-18-rococo-18th..

advertisement

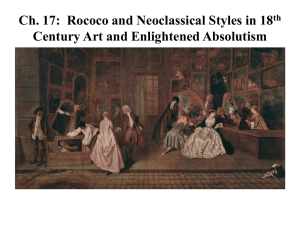

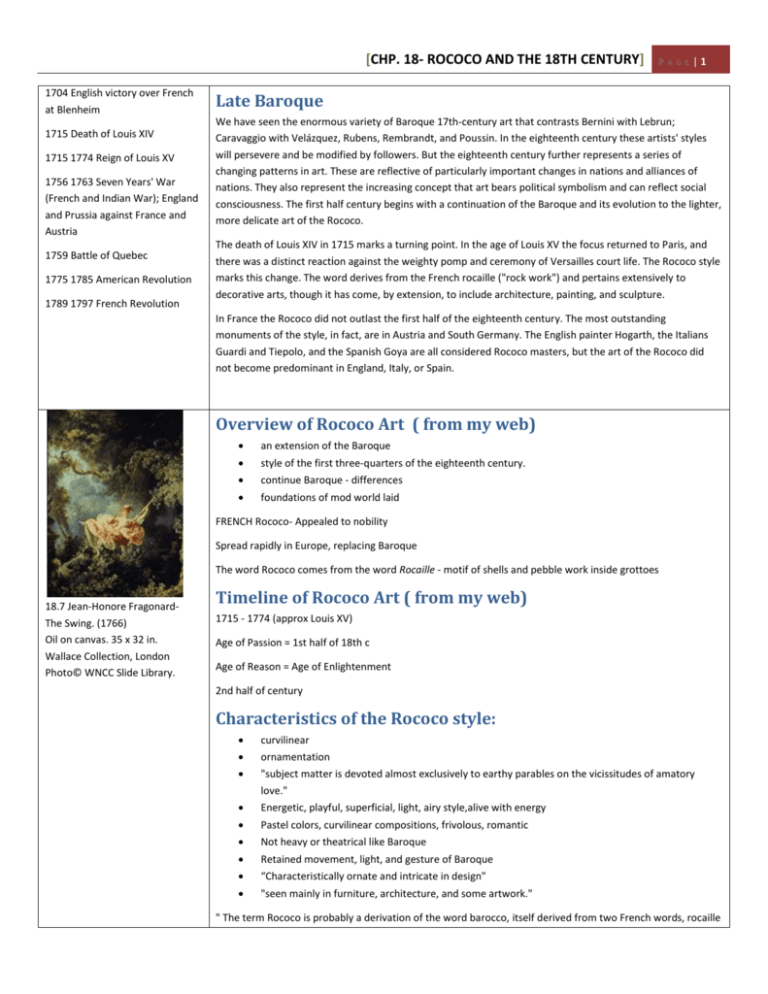

[CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] 1704 English victory over French at Blenheim 1715 Death of Louis XIV 1715 1774 Reign of Louis XV 1756 1763 Seven Years' War (French and Indian War); England and Prussia against France and Austria 1759 Battle of Quebec 1775 1785 American Revolution 1789 1797 French Revolution P A G E |1 Late Baroque We have seen the enormous variety of Baroque 17th-century art that contrasts Bernini with Lebrun; Caravaggio with Velázquez, Rubens, Rembrandt, and Poussin. In the eighteenth century these artists' styles will persevere and be modified by followers. But the eighteenth century further represents a series of changing patterns in art. These are reflective of particularly important changes in nations and alliances of nations. They also represent the increasing concept that art bears political symbolism and can reflect social consciousness. The first half century begins with a continuation of the Baroque and its evolution to the lighter, more delicate art of the Rococo. The death of Louis XIV in 1715 marks a turning point. In the age of Louis XV the focus returned to Paris, and there was a distinct reaction against the weighty pomp and ceremony of Versailles court life. The Rococo style marks this change. The word derives from the French rocaille ("rock work") and pertains extensively to decorative arts, though it has come, by extension, to include architecture, painting, and sculpture. In France the Rococo did not outlast the first half of the eighteenth century. The most outstanding monuments of the style, in fact, are in Austria and South Germany. The English painter Hogarth, the Italians Guardi and Tiepolo, and the Spanish Goya are all considered Rococo masters, but the art of the Rococo did not become predominant in England, Italy, or Spain. Overview of Rococo Art ( from my web) an extension of the Baroque style of the first three-quarters of the eighteenth century. continue Baroque - differences foundations of mod world laid FRENCH Rococo- Appealed to nobility Spread rapidly in Europe, replacing Baroque The word Rococo comes from the word Rocaille - motif of shells and pebble work inside grottoes 18.7 Jean-Honore FragonardThe Swing. (1766) Oil on canvas. 35 x 32 in. Wallace Collection, London Photo© WNCC Slide Library. Timeline of Rococo Art ( from my web) 1715 - 1774 (approx Louis XV) Age of Passion = 1st half of 18th c Age of Reason = Age of Enlightenment 2nd half of century Characteristics of the Rococo style: curvilinear ornamentation "subject matter is devoted almost exclusively to earthy parables on the vicissitudes of amatory love." Energetic, playful, superficial, light, airy style,alive with energy Pastel colors, curvilinear compositions, frivolous, romantic Not heavy or theatrical like Baroque Retained movement, light, and gesture of Baroque “Characteristically ornate and intricate in design" "seen mainly in furniture, architecture, and some artwork." " The term Rococo is probably a derivation of the word barocco, itself derived from two French words, rocaille [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |2 (rock) and coquille (shell), which were frequent motifs in the decorative arts of this period. " In contrast to the Baroque style, which was frequently employed to express religious themes on a grand scale, in bright colors, the Rococo tended to be used in a secular context on a smaller scale, expressed in subtle pastel colors.” ++ [he eighteenth century is far too complicated to be defined by period designations. Clearly the Baroque came to an end here, and the Rococo belongs to the eighteenth century alone. It is also the age of new discoveries of all sorts and of changes that will further define the modern world This urban style is associated with the Parisian salons and characterized by works of a smaller, intimate scale. The mood and subject matter are often light and frivolous. Amatory love is a dominant theme, usually depicted through mythical episodes and settings. The roots of Romanticism, the Gothic Revival, and the Neoclassical world are found in the eighteenth century. In this period the age of exploration turns to the age of exploitation, and to explosion on a worldwide stage. Revolutions in America and France stand at the beginnings of a modern world, entirely changed from the imperial past. Rococo art was the art of a particular social class—the aristocracy—and it was an art devoted solely to pleasure. Louis Vav had set the stage for this art when he centralized the rule of his country, bringing all the nobles to Versailles (Figure 19-67) from their country estates, thus transforming them from semi-independent administrators to dependent courtiers. All were dependent on the will of the king and their fortunes depended on their ability to please. While the older courtiers played the pompous game of flattery at Versailles, the younger ones became increasingly restive with the seriousness and formality of the whole affair. Having no real function to perform for society, they devoted themselves to the pursuit of pleasure, and they developed it into a fine art. Women came to play a central role in this pursuit, as well as in eighteenth-century society and art patronage. The Rococo style itself is often considered to be feminine in contrast to the masculine style of Louis XIV. Typical of the period is the figurine of Madame de Pompadour (Figure 20-7) the mistress of Louis XV and a dominant figure in the court life of her time. Compare it to the portrait of Louis XIV (Figure 20-3). The figurine of Madame de Pompadour has none of the pompous formality of that of Louis. She is shown as Venus, the goddess of love. The scale is small, and the mood is delicately playful and charming, rather than reflecting the grandeur sought by Louis XIV. This young woman had been put in training since her infancy to become mistress of the king after a gypsy predicted she would have that fate. At a masked ball held at Versailles in 1745 the king, dressed as a yew tree, met her for the first time. Within a few months, she had become his official mistress, a position she held for twenty years. She wielded considerable power behind the throne and was a generous supporter of artists and writers. Even after he had turned to other women, she remained the [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |3 king's best friend and closest confidante. She saw her role as the provider of constant distractions for the king and she did it superbly. A portrait of Madame de Pompadour painted by Boucher shows her in a casual moment, looking up from a book she had been reading. The portrait was done in the pastel colors favored by Rococo artists. You might wish to compare the pastel portrait of the Cardinal de Polignac by Rosalba Carriers (Figure 20-29) with the Rubens' Baroque portrait of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (Figure 19-43) done one hundred years earlier to illustrate the change to more informal portraiture during the eighteenth century. The shift from the formal to the informal noted in portraiture is echoed in the architectural change as can be seen from the comparison of grandiose buildings like Versailles Palace (Figure 19-65) with more intimate buildings of the Rococo. Although the Rococo style began in France, during the course of the eighteenth century it spread to many of the courts of Europe. Perhaps the most outstanding examples of Rococo architecture were built in Germany, with the gem being the Amalienburg (Figure 20-9) built in the park of the Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. The scale is small and the emphasis was on intimacy and convenience. The exterior of the building utilizes the bombe curving facade that adds a delicate grace to the building. The delicacy and gaiety of the Rococo style makes itself felt most obviously in the interiors of the building. The dining room, with its reflecting mirrors and delicate curvilinear decoration (Figure 20-14), can be compared to the majestic and somewhat overwhelming Galerie des Glaces, or Hall of Mirrors from Versailles (Figure 19-68). The Rococo preferred asymmetry and delicate silver to the symmetry and heavy gilding used in so much Baroque decoration. The charming salon from the Hotel de Soubise in Paris shown in Figure 20-2 is typical of the rooms that members of eighteenth-century French society loved to frequent. These rooms were the center of small but brilliant social gatherings where wit and grace were prized above all virtues. As the authors of the text say, WThe Rococo is essentially an interior style; it is a style of predominately small art." As architecture became smaller in scale, the sculpture and painting intended to decorate it became smaller and more intimate as well. Classical themes continued to be popular, but they took on a different meaning. No longer was homage paid to the great deities, but rather to smaller ones. The seventeenth-century group of Apollo and the Muses (Figure 19-73) made for a grotto in the gardens of Versailles, consisting of life-sized figures, a stately, impressive grouping that symbolizes the arts and their inspiration. The typical Rococo statuette shown in Figure 20-6 shows a satyr and a nymph playing on a see-saw, hardly an inspirational subject, but really quite delightful. Classical scenes of conflict like Pierro Puget's seventeenth-century version of Milo of Crotona in Figure 19-72 gave way to gentle themes like Falconet's Venus of the Doves in Figure 20-7, which, as we have seen, was a portrait of one of Louis XV's mistresses, Madame de Pompadour. The Rococo Style Rococo art was the art of a particular social class—the aristocracy—and it was an art devoted solely to pleasure. Louis Vav had set the stage for this art when he centralized the rule of his country, bringing all the nobles to Versailles (Figure 19-67) from their country estates, thus transforming them from semi-independent administrators to dependent courtiers. All were dependent on the will of the king and their fortunes depended on their ability to please. While the older courtiers played the pompous game of flattery at Versailles, the younger ones became increasingly restive with the seriousness and formality of the whole affair. Having no real function to perform for society, they devoted themselves to the pursuit of pleasure, and they developed it into a fine art. Women came to play a central role in this pursuit, as well as in eighteenth-century society and art patronage. The Rococo style itself is often considered to be feminine in contrast to the masculine style of Louis XIV. Typical of the period is the figurine of Madame de Pompadour (Figure 20-7) the mistress of Louis XV and a dominant [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |4 figure in the court life of her time. Compare it to the portrait of Louis XIV (Figure 20-3). The figurine of Madame de Pompadour has none of the pompous formality of that of Louis. She is shown as Venus, the goddess of love. The scale is small, and the mood is delicately playful and charming, rather than reflecting the grandeur sought by Louis XIV. This young woman had been put in training since her infancy to become mistress of the king after a gypsy predicted she would have that fate. At a masked ball held at Versailles in 1745 the king, dressed as a yew tree, met her for the first time. Within a few months, she had become his official mistress, a position she held for twenty years. She wielded considerable power behind the throne and was a generous supporter of artists and writers. Even after he had turned to other women, she remained the king's best friend and closest confidante. She saw her role as the provider of constant distractions for the king and she did it superbly. A portrait of Madame de Pompadour painted by Boucher shows her in a casual moment, looking up from a book she had been reading. The portrait was done in the pastel colors favored by Rococo artists. You might wish to compare the pastel portrait of the Cardinal de Polignac by Rosalba Carriers (Figure 20-29) with the Rubens' Baroque portrait of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (Figure 19-43) done one hundred years earlier to illustrate the change to more informal portraiture during the eighteenth century. The shift from the formal to the informal noted in portraiture is echoed in the architectural change as can be seen from the comparison of grandiose buildings like Versailles Palace (Figure 19-65) with more intimate buildings of the Rococo. Although the Rococo style began in France, during the course of the eighteenth century it spread to many of the courts of Europe. Perhaps the most outstanding examples of Rococo architecture were built in Germany, with the gem being the Amalienburg (Figure 20-9) built in the park of the Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. The scale is small and the emphasis was on intimacy and convenience. The exterior of the building utilizes the bombe curving facade that adds a delicate grace to the building. The delicacy and gaiety of the Rococo style makes itself felt most obviously in the interiors of the building. The dining room, with its reflecting mirrors and delicate curvilinear decoration (Figure 20-14), can be compared to the majestic and somewhat overwhelming Galerie des Glaces, or Hall of Mirrors from Versailles (Figure 19-68). The Rococo preferred asymmetry and delicate silver to the symmetry and heavy gilding used in so much Baroque decoration. The charming salon from the Hotel de Soubise in Paris shown in Figure 20-2 is typical of the rooms that members of eighteenth-century French society loved to frequent. These rooms were the center of small but brilliant social gatherings where wit and grace were prized above all virtues. As the authors of the text say, WThe Rococo is essentially an interior style; it is a style of predominately small art." As architecture became smaller in scale, the sculpture and painting intended to decorate it became smaller and more intimate as well. Classical themes continued to be popular, but they took on a different meaning. No longer was homage paid to the great deities, but rather to smaller ones. The seventeenth-century group of Apollo and the Muses (Figure 19-73) made for a grotto in the gardens of Versailles, consisting of life-sized figures, a stately, impressive grouping that symbolizes the arts and their inspiration. The typical Rococo statuette shown in Figure 20-6 shows a satyr and a nymph playing on a see-saw, hardly an inspirational subject, but really quite delightful. Classical scenes of conflict like Pierro Puget's seventeenth-century version of Milo of Crotona in Figure 19-72 gave way to gentle themes like Falconet's Venus of the Doves in Figure 20-7, which, as we have seen, was a portrait of one of Louis XV's mistresses, Madame de Pompadour. Poussin's moralistic landscape paintings, like the one in Figure 19-61, which shows the burial of the classical hero of Phocion, gave way to landscapes of pure pleasure, like the Return from Cythera shown in Figure 2G16. Elegant aristocrats are shown preparing to return from an outing on the fabled island of Cythera, the Greek island of love. Venus' statue is shown on the right wreathed in flowers, while fat cupids circle the elegantly decorated boat on the left. These paintings of aristocratic parties were known as "Fetes galantes." This work was painted by the greatest master of the fete galante, Antoine Watteau. Although he is the most famous painter of the eighteenth-century aristocracy, he was himself from the lower classes. It was only with the greatest difficulty that his parents managed to give him the education he needed to become a painter. He got to know the guard at the Luxembourg Palace in Paris who he persuaded to let him in to see the paintings that Rubens had done for Maria de' Medici. He studied the Flemish master and many feel improved on his coloring. He even went further than had Rubens in loosening his brushwork and his glancing, shimmering lights are [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |5 forerunners of the Impressionist brushstroke. L'Indifferent (Figure 20-15) demonstrates his exquisite handling of the brush, the glancing white lights that make the satin ripple and glow, and the marvelous sense of airy atmosphere he gets in the background. Watteau's successors never quite matched his taste and subtlety. The most famous painter of the mid-eighteenth century was Francois Boucher, the favorite of Madame de Pompadour. Boucher became her chief stage designer and master decorator. In his paintings the female figure triumphs, women, alluringly undressed, are everywhere, as you see in the image of Cupid a Captive (Figure 20-5). Pierre Schneider feels that the ladies Boucher represents cannot altogether disguise their real occupation, for a trace of vulgarity lurks beneath their elegance. The nymphs and divinities are opera girls (a bit like the show girls of our time) in disguise. One of his contemporaries observed that "Boucher had not seen the graces in the right sort of places." Boucher served as teacher to the last of the great Rococo painters, Jean Honore Fragonard, whose painting The Sunng is shown in Figure 20-4. His brilliant but impatient pupil won the prix de Rome on his first try in 1752. Boucher had some apprehension about how Fragonard would react to Rome and warned him, "If you take Michelangelo and Raphael seriously, you are a lost fellow." While in Rome he became more interested in the work of Baroque painters like Pietro da Cortona, whose painterly approach was more like his own. On his return from Rome, he joined the Academy and tried doing noble pictures, but they were dismal failures. Instead he decided to do the more saleable frivolous subjects. This painting is certainly frivolous, for it shows a young man enjoying a special view of the young woman on the swing. The following story explains the somewhat singular composition. A rich personage had called in the painter called Doyen, and pointing to a young woman with whom he was clearly on terms of intimacy, he explained to the artist that he would like him to depict her soaring high on a swing pushed by a bishop while he himself would be reclining in the grass, savoring the spicy spectacle of her flying skirt. Doyen was taken aback, not so much by the nature of the request as by the fact that it should be addressed to him, a painter of religious scenes. He referred the man to Fragonard, with the result that you see. Fragonard's style was well adapted to such scenes—his lightness and mobility tell the story with a frivolity and superficiality that seems to sum up his age. Although the Rococo was essentially a secular style, a number of German architects made great use of it in a series of spectacular eighteenth-century churches built in Bavaria, such as Neumann's pilgrimage church of Vierzehnheiligen, which commemorated the fourteen saints who had appeared miraculously to a local shepherd (Figure 20-15). The Bavarian pilgrimage churches owe more to the Italian buildings of Borromini and Guarini than to the French, and in many ways they can be considered as a mixture of Baroque and Rococo. The undulating facade of the exterior owes much to the Italians, but the interior (Figure 20-16) is more delicate than the Italian examples. There seem to be no straight lines, and even the entire plan is made up of interlocking ovals (Figure 20-18). The German decorators sometimes got carried away with details such as the shrine in the center that almost seems like a candy confection. The Asam brothers created a series of churches that combined incredibly rich decoration with a dramatic type of illusionistic theater. In the Assumption of the Virgin from the monastery church at Rohr (Figure 20-19) we see a German version of the sacred theater so well presented by Bernini almost a hundred years earlier (Figure 19-12). The stone figure of the virgin seems weightless as it is borne aloft by the angels. Here we see a final statement of the triumphant Catholicism put forth by the Council of Trent. The triumph of the Virgin Mary is reasserted in both palpably physical and transcendently spiritual terms. These Bavarian churches were often painted with ceiling frescoes, many of which emulated the work of Tiepolo, the last of the great Italian painters to have an international impact. One of his ceilings illustrated in Figure 20-14 is from the villa of an Italian family, and shows their apotheosis. He travelled to many of the courts of Europe, painting frescoes that recalled the great Italian Baroque ceilings but with a much lighter touch. Neumann and Tiepolo collaborated to create the masterpiece in the Bishop's palace or Residenz at Wurzburg. Neumann designed the building and the magnificent staircase while Tiepolo did the ceiling above using the theme of the four continents. [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |6 Suggested Images: Figures 19-12, 19-43, 19-61, 19-65, 19-68, 19-72, 19-73, 20-1, 20-2, 20-3, 20-4, 20-5, 20-6, 20-7, 20-8, 20-9, 20-10, 20-12, 20-14, 20-15, 20-16, 20-17, 20-18, 20-19, 20-20, 20-29 Quoted: 2 The Art of the 18th Century Bourgeoisie The aristocrats who commissioned the charming Rococo decorations were not the only eighteenth-century patrons of the arts. During the eighteenth century wealthy members of the bourgeoisie came to take an ever more important role in both politics and society, and the works of art they bought were not those favored by the aristocracy. The greatest painter of the eighteenth-century bourgeoisie was Jean Baptiste Chardin, who is remembered for still lifes and for scenes such as the one illustrated in Figure 20-26. Chardin's quiet compositions are closest to those of the great seventeenth-century Dutch Master Vermeer (Figure 19-54), who also painted for bourgeoise patrons. Chardin's colors are a bit warmer than Vermeer's, but the work of both artists breathe a serenity that sets them off from the work of other contemporary painters. Both found great pleasure in the quiet beauty of simple things, and both imbued the commonplace with an uncommon dignity. In Chardin's simple but monumental composition of Grace at Table (Figure 20-26) Chardin has organized all the elements of his composition into a stable monumental pyramid, yet the woman looks completely natural and at ease as she bends over the table, setting food before the children. The composition contains a number of his favorite colors and textures; the whites of clean linens, the warmth of garments, and above all the soft glow of copper. The theme of simple piety and homey virtues reflects the values of the middle class. This simple composition is quite different from all the fancies of the contemporary Rococo. It is hard to imagine that Chardin was working in the same period and in the same country as Boucher and Fragonard. The simple piety of Chardin becomes moralistic preaching in the works of Jean Baptiste Greuze (Figure 20-37). This work, called The Wicked Son Punished, is part of a series devoted to the prodigal son. The dramatic poses and histrionic gestures are undoubtedly influenced by the exaggerated gestures of the theater, which was extremely popular in the eighteenth century. Compare this scene with the quiet but deeply moving joy with which Rembrandt's aged father welcomes home his wandering son (Figure 19-50). By contrast Greuze shows the son's punishment, for the son comes home to find the father dead and the rest of the family in hysterics. The work gives a moral sermon, and although most of us tend to recoil a bit from this sort of over-done moralism, it was quite possibly a necessary antidote to the excesses of Rococo eroticism. When Louis XVI, who was moral to the point of prudishness, came to the throne in 1774 he ordered Boucher's erotic paintings destroyed. Greuze became the painter of the day, for his work was considered to inspire virtue. Moralistic art existed in eighteenth-century England as well, but it was of a somewhat less hypocritical nature than much of Greuze's productions. For example, consider the work of William Hogarth, whose moralism was always spiced with satire. His work, like Figure 20-36, shows the influence of the eighteenth-century theater, just as did that of Greuze. This is one of the scenes from his famous series known as Marriage a La Mode, dealing with a common eighteenth-century situation: the marriage of a bourgeois girl to an aristocrat because her parents are after his title and he is after their money. This episode shows the breakfast scene in which both husband and wife are exhausted after a long night in someone else's company. In another episode a young girl is taken to a quack for treatment for the venereal disease she has contracted from the dissolute husband, while in another the husband returns home to find his wife's lover fleeing out the window and kills him. Such genre paintings are closely related to the comedies of rnanners so popular in eighteenthcentury theater. Moralistic messages were also delivered in the Neoclassic guise that became popular later in the eighteenth century. Angelica Kauffmann's painting of Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi (Figure 20-39), illustrates the popular mode of presenting a model of virtue or exemplum virtutis from the literature of Greece and Rome. Although presenting a classical theme, Kauffmann's style showed the stylistic legacy of the Rococo, a legacy that was resolutely rejected by Jacques Louis David, whose Oath of the Horatii (Figure 20-40) is the most famous example of a classical model of virtue. This painting, completed in 1784, and illustrating the willing sacrifice of three young men for the integrity of the Roman Republic, was interpreted by the French bourgeoisie as a call to revolution, and David became the painter of the French Revolution. The austere style of the Oath of the Horatii, with its shallow space, its rigorous linearity, its carefully modelled figures and precisely painted archeological details, was to set the model for Neoclassic academic painters of the nineteenth century. While many of them turned out cold and pompous compositions, David was able to use the rigors of the style to create such dramatic and compelling images as The Death of Marat (Figure 20-41). Using a starkly simplified composition, he presents us with the reality of the murder of the revolutionary hero Marat, stabbed in his bath by Charlotte Corday, who had become convinced that the excesses of the Revolution must be stopped. David's skills as a portraitist were in great demand during the period of the Directoire and the Empire. For many of these portraits he drew on the tradition of naturalism that had developed in late eighteenth-century portraiture. The work of Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun is an excellent example of this [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |7 trend. In her self-portrait (Figure 20-23) she presents herself calmly and naturally, and we seem to have caught her as she glances up from her work, looking at us as though we were the sitter she is painting. Portraits were by far the most important production of eighteenth-century English artists who were in demand by both aristocrats and wealthy merchants. The tradition of portraiture begun by the seventeenth-century Fleming Anthony Van Dyck still flourished in England. Van Dyck, a pupil of Rubens, had brought an elegant version of Baroque portraiture to England in the early seventeenth century. His portrait of King Charles I is shown in Figure 19-44. Van Dyck's rich texture, loose brushwork, and his elegance were reinterpreted by artists like Gainsborough in the eighteenth century (Figure 20-22). This work is very close to the delicacy and elegant artificiality of the contemporary French Rococo, but without the erotic overtones. Although Gainsborough made his living by painting portraits, he much preferred to paint landscapes, and when he could he set his figures in delicate freely painted landscapes, as he did here. Figure 20-30 shows a very different kind of eighteenth-century English portrait, the dramatic rugged military portrait of Lord Heathfield by Gainsborough's chief rival, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds is best known for his portraits, and like Gainsborough, he preferred to paint in another genre. As the President of the newly founded Royal Academy, he advocated history painting as the most noble, and wrote that one should paint in the "generals manner of the Italians rather than emphasizing realistic details as did the Dutch. His own efforts in this area are not considered nearly as interesting as are his portraits. Benjamin West, an American artist working in London did, however, do a number of very fine history paintings in the grand manner advocated by The Royal Academy. As a matter of fact, he succeeded Reynolds as its president. In his depiction of The Death of General Wolfe (Figure 20-38) West combines heroic sentiment and dramatic Baroque compositional structure with realistic details of the contemporary military costume. While West's innovations would influence much of nineteenth-century history painting, the work of his contemporary Joseph Wright of Derby would be more influential in the scientific world. His painting of A Philosopher Giving a Lecture at the Orrery (in which a lamp is put in place of the sun) (Figure 20-28) was but one of a number he did depicting the scientific research of his time. He used lighting techniques similar to the seventeenth-century Caravaggisti to add drama of this lecture that teaches the orbits of the planets around the sun. His work is an important example of the Enlightenment fascination with discovering the laws of the real world. The American love of the real can be seen in the Portrait of Paul Revere by John Singleton Copley (Figure 20-20). Here we find a somewhat austere and direct portrayal of his sitter without the niceties added by his European contemporaries. One of the greatest of the eighteenth-century portraitists worked in sculpture rather than painting: Jean Antoine Houdon. He portrayed some of the most influential men of his age, including Jean Jacques Rousseau, the young Marquis de Lafayette who had returned from America where he had helped to fight for the young Republic, Thomas Jefferson, the old Ben Franklin, and George Washington. He depicted them all in contemporary dress. However, the stoic morality of ancient Rome was an important model to these men for the reshaping of their own times. Artists like Houdon reflected the influence of their ideas in works like the one on Figure 20-24, which shows the philosopher Voltaire dressed in the toga of a Roman senator. However, unlike many later artists who worked in the Neoclassic style, Houdon never lost the immediacy of life, for the old Voltaire is depicted with tremendous vitality. Suggested Images: Figures 19-44, 19-50, 19-54, 20-20, 20-21, 20-22, 20-23, 20-24, 20-26, 20-28, 20-30, 20-31, 20-32, 20-36, 20-37, 20-38, 20-39, 20-40, 20-41, 20-44, 20-50 3~ Architectural Uses of the Past English artists did not contribute a great deal to the development of European visual art during the Renaissance. However, in the early seventeenth century a young architect, Inigo Jones, introduced a vital architectural tradition to England with the building of the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall (Figure 19-74). Jones had utilized many of the motifs and proportions of the Venetian Renaissance architects. Although Jones was strongly influenced by Palladio, the Banqueting Hall shares many features with Sansovino's State Library in Venice (Figure 17-50). Notice how Jones uses similar engaged columns on the facade, a clear and logical structuring of the parts, with emphasis on the horizontal structure of the building, relieved only by the graceful decorative swags at the top of the building. Sansovino had used that motif most effectively, just as he had used a balustrade around the top. Jones did not, however, add statues along the top of the balustrade as had been common on Italian villas. Palladio exerted a lasting influence on Jones through his books on architecture, which served as a source for motifs as well as proportions. Sir Christopher Wren also used many Renaissance details on his masterpiece, St. Paul's cathedral in London (Figure 19-75), but many features, such as the towers, seem to show the more Baroque influence of Borromini. The lower portion of the building is more restrained and classical than the [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |8 upper section, with the doubled columns of the portico recalling Perrault's facade of the Louvre. Yet these two very different stylistic tendencies are harmonized by Wren. The restrained Palladian tradition introduced by Jones and the more Baroque approach of Wren are both represented in English architecture of the eighteenth century. The Baroque tradition is represented by the great palace of Blenheim (Figure 20-11), built in the early eighteenth century by Sir John Vanbrugh. As Kenneth Clark points out, Vanbrugh was an amateur, a fact used by some critics to explain the somewhat incongruous elements he combines in this massive building. Voltaire commented that "if only the rooms had been as wide as the walls were thick, the palace might have been convenient enough." Much more convenient was the group of houses shown in Figure 20-42, the Royal Crescent at Bath, which is a beautiful eighteenth-century example of city planning. This group of what would today be called attached town houses or condominiums was laid out around a generops expanse of the common green. The simple classical lines of this building combine elegance and grace of structure with a rare sense of the relation of an individual building to the surrounding space. Of a similar spirit is the eighteenth-century villa in Figure 20-1, known as Chiswick house, which had been built near London about 1725. The simple symmetry of this building, the cubic shape crowned by the dome, and the simple classic porch are all reminiscent of Palladio's Villa Rotonda (Figure 17-51). Chiswick House is typical of the so-called Palladian style that became so popular in eighteenth-century England. The building with its clear symmetrical structure and mathematical proportions seemed a fit setting for the gentlemen of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, men who shared the belief in the power of reason, in the human scale, and in individual dignity set forth so clearly by the Italian Renaissance. Monticello (Figure 20-42), was designed and built some 50 years later by one of the most famous American representatives of the Enlightenment, Thomas Jefferson. Working only from an architectural treatise by Palladio, this talented amateur architect designed a villa for himself that would set the architectural tradition for the mansions of the ante-bellum south. Jefferson felt that classical buildings were important democratic symbols for the new republic, and he used a more massive neoclassical style for his design of the state capitol at Richmond, Virginia. Jefferson had seen the Roman temple at Nimes (Figure 6-46), and reflected its influence in the capitol building he designed at Richmond. The Roman Pantheon (Figure 6-56) served as the model for the library he designed for the University of Virginia in Charlottesville (Figure 20-32). Jefferson was influential in setting the style for official government buildings like Latrobe's capitol building that was constructed in Washington, D.C. (Figure 20-22) in the early years of the nineteenth century. The influence of the more massive Roman classical style reflects the young republic's attempt to identify with the virtues of Roman republicanism. The Americans may also have been influenced by the French architect Soufflot's brand of monumental classicism shown in Figure 20-36. The building, called the Pantheon, is in Paris, and was used by French revolutionaries as a temple to divine reason, a variation of the function of the original Roman Pantheon as a temple to all the gods. The Roman city of Pompeii, which had been completely covered by lava flows in the first century, was excavated in the 1730s and 1740s and the newly discovered motifs offered a whole new repertoire to architects and interior decorators. In the second half of the eighteenth century such classical motifs became popular for interior decoration, particularly in England. Osterley Park House, designed by Robert Adam, is an excellent example of the new style. One room of the house, called the Etruscan Room, is illustrated in Figure 20-37. The ceiling uses the raised stucco technique so popular with the Romans, while the motifs used for the wall decoration—affronted griffins, vases, garlands, and putti, are all taken over from the decorative motifs uncovered in Pompeii. The spare decorative style with its empty spaces and delicate rinceaux patterns was known as the Pompeiian style. How different is the relative austerity of this room from the German Rococo extravaganza from the Amalienburg (Figure 20-14) which was done about the same time. The admiration for classical antiquity became virtually a passion for many eighteenthcentury gentlemen, and it became very fashionable to have bits and pieces from excavations of ancient sites. It also became very fashionable to have classical ruins on the grounds of one's country house. Since the Romans left more walls and military encampments in England than they had left temples, the gentlemen built their own ruins, like the one shown in Figure 20-41. This little building is only a facade and was especially constructed as "aged" ruins. An important aspect of Romantic architecture was the revival of medieval gothic forms; this is called the Gothick Revival. Gothick "follies," or phoney ruins are like the one shown in Figure 20-40. Strawberry Hill (Figure 20-39) is a building that was built by Sir Horace Walpole as a Gothick castle. He used this as his country house. The house formed the setting for recreations of an earlier period, and as a playful escape from his heavy governmental responsibilities. One senses that the eighteenth-century Enlightenment love of classical clarity and logic here has come very close to the eighteenth-century Rococo love of fantasy and play. This view of the past was popularized by the eighteenth-century Roman etcher Piranesi. His famous view of Rome, which looks nostalgically back at the Xglory that was Rome," evokes a spirit that we associate with Romanticism. In another series, the Carceri (Figure 20-33) Piranesi evokes massive [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E |9 Roman ruins in the creation of an oppressive series of prisons. While the Baroque spirit tended to be outgoing and bursting with energy, the Romantic spirit was more brooding and often tried to escape into another age. It is a spirit in opposition to the optimism of both the Baroque and the eighteenth-century rationalism of the Enlightenment. The seeds of twentieth-century International Style architecture, with its concept that "form follows function," and its honest, economical, and elegant use of materials, are found in such eighteenth-century works as the Cookbrookdale bridge (Figure 20-19). Nineteenth-century engineers and architects will further develop these tendencies. In addition the revival of architectural styles begun in the eighteenth century continued in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. After a period of domination by austere building in the International Style, revival styles are again emerging. You might wish to give your students the assignment of seeing how many buildings in their area they can find that obviously use architectural forms from the past. Suggested Images: Figures 6-46, 6-56,17-50,17-51,19-74, 19-75, 2G1, 20-11, 20-14, 20-19, 20-21, 20-22, 20-32, 20-33, 20-36, 20-37, 20-38, 20-39, 20-40, 2W1, 20-42, 20-44, 20-45, 20-46 Rococo Painting Rococo art, which flourished in France and Germany in the early 18th century, was in many respects a continuation of the baroque, particularly in the use of light and shadow and compositional movement. Rococo, however, is a lighter, more playful style, highly suited to the decoration of, for example, the Parisian hôtels (city residences of the nobility). Among rococo painters, Jean-Antoine Watteau is known for his ethereal pictures of elegantly dressed lovers disporting themselves at fêtes galantes (fashionable outdoor gatherings); such pastoral fantasies were much emulated by other French artists. Highly popular also were mythological and pastoral scenes, including lighthearted and graceful depictions of women, by François Boucher and Jean Honoré Fragonard. J. B. S. Chardin, however, took a different view, portraying women in his genre scenes as good mothers and household managers; he also was outstanding in rendering still-life. The rococo style in Germany is exemplified by the work of the Italian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who spent some time in Würzburg, Germany; his huge illusionistic ceiling frescoes (1743-1752) decorate the staircase hall and the Kaisersaal (the main reception hall) of the Residenz, the episcopal palace in Würzburg. Paralleling the rococo tradition of the continent were the works of three major artists of 18th-century England. William Hogarth was known for his moralistic narrative paintings and engravings satirizing contemporary social follies, as in his famous series (first painted and then engraved) Marriage à la Mode (1745), which traces the ruinous course of marriage for money. Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds, following the tradition established by van Dyck, concentrated on portraits of the English aristocracy. The verve and grace of these paintings and their astute psychological interpretations raise them from mere society portraiture to an incomparable record of period manners, costumes, and landscape moods. See Rococo Style. Part 5: Unit Exam Essay Questions (from previous Art 261 tests) (from AAT4) Discuss Enlightenment philosophy. How is it reflected in the arts? Use examples in your text. Using examples from your text, compare Rococo with Baroque. Consider style, context, and subject matter. Discuss the role of irony and satire in the art of William Hogarth. Compare American painting of the eighteenth century with that of England and France. Use the examples in your text. Discuss the iconography of Benjamin West's Death of General Wolfe, considering his portrayal of contemporary events. (from other) Discuss Enlightenment philosophy. How is it reflected in the arts? Use examples in your text. Using examples from your text, compare Rococo with Baroque. Consider style, context, and subject matter. Discuss the role of irony and satire in the paintings of Watteau. Compare American painting of the eighteenth century with that of England and France. Use the examples in your text. Discuss the contemporary and the historical features of the iconography of West's The Death of General Wolfe. Learning Goals (AAT4) After reading Chapter 18, you should be able to do the following: Identify the works and define the terms featured in this chapter [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] Define the stylistic traits of Rococo Discuss chinoiserie in eighteenth-century art Discuss the development of the salons Explain the significance of the Enlightenment Describe the beginnings of art history as a discipline Trace the spread of the Rococo style in Europe Discuss the role of satire in Hogarth's prints Explain what is meant by "Bourgeois Realism" Describe the Rococo style in America Label the North American settlements on a map of the east coast of the United States Discuss the revival of architectural styles in the eighteenth century Describe the emergence of American painting, discussing its relationship to European art Chapter Outline (AAT4) ROCOCO AND THE 18th CENTURY Age of Enlightenment Science: Priestley; Halley; Leibniz Music: Vivaldi; Bach; Haydn; Mozart Literary satire: Voltaire; Swift Sturm und Drang in Germany: Goethe The encyclopédistes: Diderot Political philosophers: Locke; Rousseau Seven Years' War (1756–1763) American Revolution (1776) The U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights French Revolution (1789) Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette guillotined (1793) Art patronage moves from Versailles to the Paris salon Revival styles: Chinoiserie; discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum Winckelmann and the beginning of art history Painters in France: Watteau; Boucher; Fragonard; Rigaud; Vigée-Lebrun; Labille-Guiard; Chardin; Carriera Painters in England: Wright; Gainsborough; Hogarth; Kauffmann Painters in America: Copley; West German architects: Neumann; Pöppelmann; Zimmermann Tiepolo in the Kaisersaal Architects in England: Lord Burlington; Adam; Walpole Art Theory: Winckelmann; Kant; Hege Summary and Study Guide Late 1700’s to Mid 1800s P A G E | 10 [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E | 11 The Age of Enlightenment (from my web) Characteristic of Enlightenment: Voltaire Denis Diderot - Encyclopedia systematic gathering and ordering of data from natural world, leads to understanding of oneself & the world power of knowledge & education to improve human life and the renewed interest in naturalism leads to both: revival of classicism beginning of Romantic (Goethe) moral painting : details of accurate observations from life: Chardin, Hogarth Scientific Experiments in the Enlightenment (from my web) Art Theory and the Beginnings of Art History (from my web) The Rococo, Enlightenment, Neoclassicism and Romanticism (AP Art History) Terms be able to identify these by sight, explain these in relation to art, and know an example of each in relation to a work of art Rococo archeology Enlightenment Johan Joachim Winckelmann philosophes Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Art in Painting and salon Sculpture by Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1755) Encyclopédie by Denis Diderot (1713‐1784) History of Ancient Art by Johann Joachim Winckelmann the Grand Tour (1764) Industrial Revolution Napoleon Bonaparte (1769‐1821) fête galante Romanticism Poussinistes age of revolutions (American, French, and Greek) Rubénistes Crenellation [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E | 12 Madame de Pompadour the great rivals: Ingres vs. Delacroix Prix de Rome the Salon Neoclassicism Delacroix’s trip to North Africa and journals excavations at Herculaneum (begun in 1738) and Pompeii Hudson River School (begun in 1748) Art Works know these works by sight, title, date, medium, scale, and location (original location also if moved) and be able to explain and analyze these in relation to any concept, term, element, or principle The Oil on canvas, otta Vigée‐Lebrun, Self‐Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas th, Breakfast Scene, from Marriage à la Mode, c.1745, oil on canvas 5’ 5/8”. Derby, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture at the Orrery (in which a lamp is put in place of the sun), c.1763¬1765, oil on canvas n Singleton Copley, Portrait of Paul Revere, c.1768‐1770, oil on canvas lottesville, , George Washington, 1832‐1841, marble es‐Louis David, , England, b.1725 Blake, Ancient of Days, frontispiece of Europe: A Prophecy, 1794, hand colored etching Francis Devouring His Children, 1819‐1823, detail of a detached fresco on canva 818‐1819, oil on le, 1830, oil on canvas –La Marseillaise, Arc de Triomphe, Paris, 1833‐1836, limestone [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E | 13 Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, oil on canvas the Missouri, c.1845, oil on canvas Delacroix, ca. 1855. ylvania, July 1863. Modern print* (*Nadar and O’Sullivan took their pictures and produced the negatives in the year listed, the print from this negative however was made more recently by some other dude.) AAT4 Key Terms chancel that part of a Christian church, reserved for the clergy and choir, in which the altar is placed. chinoiserie a Western style popular in the eighteenth century, reflecting Chinese motifs or qualities. fleur-de-lys (a) a white iris, the royal emblem of France; (b) a stylized representation of an iris, common in artistic design and heraldry. hôtel in eighteenth-century France, a city mansion belonging to a person of rank. impasto the thick application of paint, usually oil or acrylic, to a canvas or panel. krater a wide-mouthed bowl for mixing wine and water in ancient Greece. molding a continuous contoured surface, either recessed or projecting, used for decorative effect on an architectural surface. pagoda a multistoried Buddhist reliquary tower, tapering toward the top and characterized by projecting eaves. stucco (a) a type of cement used to coat the walls of a building; (b) a fine plaster used for moldings and other architectural decorations. trompe l'oeil illusionistic painting that "deceives the eye" with its appearance of reality. Chronology Art Works know these works by sight, title, date, medium, scale, and location (original location also if moved) and be able to explain and analyze these in relation to any concept, term, element, or principle Summary and Study Guide “The Eighteenth Century” “Rococo” “Rococo, an extension of the Baroque, was a style of the first three-quarters of the eighteenth century. Characteristically ornate and intricate in design, it is seen mainly in furniture, architecture, and some artwork. The term Rococo is probably a derivation of the word barocco, itself derived from two French words, rocaille (rock) and coquille (shell), which were frequent motifs in the decorative arts of this period. In contrast to the Baroque style, which was frequently employed to express religious themes on a grand scale, in bright colors, the Rococo tended to be used in a secular context on a smaller scale, expressed in subtle pastel colors.” “Jean-Antoine Watteau” “The work of the French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) illustrates the decorative and sometimes lighthearted treatment of the Rococo. In his heritage, Watteau was Flemish, and the influence of Rubens can be seen in his work. (Watteau's French nationality came about because of a treaty signed a few years before he was born according to which the part of Flanders in which he lived became French territory.) His mastery of gesture and light and color are apparent in his paintings L'Indifferent (1720-1721) and Gersaint's Signboard (1720¬1721). In [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] P A G E | 14 L'Indifferent, Watteau portrays a dancer, possibly performing the minuet, a popular couples dance of the period. In Gersaint's Signboard, the characters do not interact with the viewer but with one another. In a rather lighthearted fashion, Watteau presents a picture of an everyday scene in the life of high-society France, as the elegant members of that class shop for paintings with which to decorate their homes. Perhaps Watteau's best-known painting is A Pilgrimage to Cythera (1717). As is characteristic of much of his work, the figures are in small groups, their scale small in the landscape, which, although somewhat idealized through the artist's brush, retains a naturalistic ambience.” “Francois Boucher” “Watteau's successor was Francois Boucher (1703-1770), who had as a patron Madame de Pompadour. His favorite theme and subject was the female nude, which he depicted in a Classical manner, as seen in Cupid a Captive (1754). Here he has modeled his figures three dimen¬sionally, and they form a triangle in the center of the painting. The ornamentation and intricate style of the Rococo era are seen in com¬bination with the traditional Baroque manner of composition, with the landscape receding through slanting planes and strong diagonals. Whether nude or clothed, his female figures were typically depicted in subtle shades of pink, accenting the form rather than the substance of the character. Boucher's portrait of Marquise de Pompadour (1759), mistress and advisor to King Louis XV, reflects his ability to manipulate color and to portray the intricate details of a costume that is layers thick, as well as to capture the ambience of a time that many have considered superficial and frivolous.” “Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin” “The style and themes expressed by artists such as Boucher that appealed to the interests and tastes of the aristocrats were considered by much of the middle class to be frivolous, and the work of artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin (1699-1779) was found to be more appealing. Chardin tended to focus his skills on the depiction of still lifes and everyday scenes from the lives of the middle class, as seen in Grace at Table (1740). His paintings are calm and serene compared to those of Boucher.” “Chardin also enjoyed portraying children, as in his painting The House of Cards (1741). The sense of intensity between the standing cards and the boy's concentration as he builds his "house" is reinforced by the artist's use of light to highlight the boy's face, the cards, and an open drawer, forming a triangle. Chardin's attention to the relationship between form and value lends a sense of strength and dignity to his paintings.” “England” “William Hogarth” “During the seventeenth century, there were few notable English painters, and until the time of William Hogarth (1697-1764), the English aristocracy typically engaged such artists as Holbein and Rubens to produce works of art. Though Hogarth's work was likely influenced by the art of the French Rococo, his painting was charac¬teristically English in reflecting the age of satire in which he lived. He was fond of doing series, such as his Marriage d la Mode, which portrayed the marital travails of a young viscount. The Breakfast Scene (1745) from that series portrays the disheveled young couple on the morning after a late night out, and it is apparent that all is not well. A servant exits the room, for example, carrying unpaid invoices, while the young nobleman sits slumped in a chair, pockets empty from gambling. The decor of the room itself is a parody of the style of the time, and there are numerous details in the image that challenged the standards of eighteenth-century English society.” “Thomas Gainsborough” “Though Hogarth's genre paintings were quite popular, it was the portrait at which English painters excelled. Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), known for his landscapes as well as his portraits, treats the portrait differently in his paintings The Honourable Mrs. Graham (1775) and Mrs. Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1785). In the former portrait, Gainsborough has portrayed Mrs. Graham next to a solid column, her dress and expression indicating her social status. Mrs. Sheridan, however, is placed in a rural landscape setting, enveloped by an airy atmosphere.” “Joshua Reynolds” “A contemporary of Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), also known as a portraitist, was skilled in conveying the character of his subjects, as in his portrait of Lord Heathfield (1787).” Discussion topics for this chapter. Discuss Enlightenment philosophy. How is it reflected in the arts? Use examples in your text. Using examples from your text, compare Rococo with Baroque. Consider style, context, and subject matter. Discuss the role of irony and satire in the paintings of Watteau. Other topics to consider: [CHP. 18- ROCOCO AND THE 18TH CENTURY] Compare American painting of the eighteenth century with that of England and France. Use the examples in your text. Discuss the contemporary and the historical features of the iconography of West's The Death of General Wolfe. P A G E | 15