Roethke's My Papa's Waltz: Ambiguity & Interpretation

advertisement

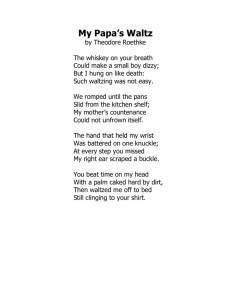

The Ambiguity of Connotation and Structure: Ambivalent Result In “My Papa’s Waltz” (1948), Theodore Roethke paints a picture of a father-son romp around the kitchen that is at the same time both rough in its play, and tender in its memory. Roethke uses simple words to create ambiguous phrases that can be read and understood in these two different ways. The imagery in the poem is full of confusion as to what the actual meaning is. The poem is also semiautobiographical, so Roethke is creating these images from his childhood memories. In describing a purpose of poetry, he said himself that “poetry is the discovery of the legend of one’s youth” (Blessing 18). But legends are a mix of actual physical truths combined with story telling that paints a picture showing the way we would like to remember the past. The fact that poetry discovers the legend means that the story within the poem has both hard truths and fanciful memories. Roethke’s creates this legend using ambiguity of language combined with the poem’s structure and connotation. The structural frame of “My Papa’s Waltz” creates confusion in meaning among the stanzas. The poem is not uniform. Few structural points are similar in the four stanzas. Each stanza is one complete sentence, has an ABAB rhyme scheme, and is written in “iambic trimeter” (Fong). The iambic trimeter creates a waltzing beat that flows through the poem. However, there is a variance in this pattern with five lines having an extra beat in them. This variance, or misstep, could have been written for two very different reasons. One reason could be that there is a sense of carefree feeling in the waltz. The father doesn’t have to be in perfect step to enjoy dancing with his son. He is playing with his son. The other reason could relate to the whiskey mentioned in the first stanza. The father could be drunk or tipsy and is taking extra steps in dancing due to the lack of sobriety. The most reasonable answer may be found in further exploring the structure. Butler2 The rhyme scheme plays a part in the missteps of the poem, too. The first two stanzas contain slant rhyme and straight rhyme, while the last two stanzas contain only straight rhyme. This slant rhyme is observed with “dizzy” and “easy,” and with “pans” and “countenance.” The explanations for the slant rhyme create another ambiguity. First, “dizzy” and “easy,” being slant rhyme, could be emphasis on the action of these words. It could create a sense of drunkenness, or that of a sense of carefree fun. This delves into the words connotations, which will be discussed later. Second, the pattern of two slant rhymed stanzas followed by two straight rhymed stanzas creates the possibility for two interpretations of this pattern. The slant rhyme creates a sense of strain and unevenness in the work. At the same time, the slant rhyme could mean that there is a resourcefulness that the writer exploits, using words that necessarily would not pair. With straight rhyme, the writer can create a sense of resolve. The writer has a more concrete sense of the work and can translate it in the straight rhyme. On the other hand, the straight rhyme can show a sense of chaos. Human nature uses structure as a coping mechanism. When things inwardly become hectic or chaotic in one’s life, human nature tends to strive for the outward appearance of neatness and structure. The chaos in the poem is created through the meaning and connotations of the words, and the straight rhyme is the writer’s attempt to create structure out of chaos. The ambiguity that arises from connotations of the words that starts from the very first stanza. “The whiskey on your breath/ could make a small boy dizzy;/ but I hung on like death:/ such waltzing was not easy.” The first two lines create a double meaning. The “whiskey on your breath” could mean that the father was an alcoholic but Butler3 it could mean that the father had just a sip of whiskey. The sip of whiskey could have made the child dizzy because any child thinks alcohol smells strong. This creates an uneasiness with the father and son relationship. What are we supposed to believe is the true meaning? The second two lines create another sense of uneasiness. First, the son is waltzing with the father, which creates a sense of fun. Yet, this son is only tall enough to reach his dad's belt buckle. With a huge dad like this, the son would have to cling to his dad using every tiny muscle available to him as he was being twirled around the room. This is the son's memory. From the son's perspective the interactions are a bit overwhelming. The father is having fun with his son and is unknowingly creating a minor sense of fear in the child. The game was played too harshly for the young boy, as seen with the words “hung on like death” and “not easy.” It was a memory that might have been fun to a certain point, but was taken over-the-top by the father. The second stanza confirms the fact that the father might have taken things too far. “We romped until the pans/ slid from the kitchen shelf;/ my mother’s countenance/ could not unfrown itself.” The “romp” suggests a playful behavior between the father and son. The force created by the romp was so strong that it was making a mess of the kitchen. This suggests that the interaction could have been too much for a small boy. Clearly, the mother is not very happy with the interaction. The “mother’s countenance” would not be “unfrown[ed]”. Two images are visible with the mother’s reaction. First, the mother is only dismayed that her kitchen is being destroyed. Second, the mother is not only dismayed that her kitchen is being torn apart, but she is not fully enjoying the rough-housing between the father and son. She is not stopping the interaction, which suggests that she is approving that the father is playing with the son. Yet, the fact that she is frowning suggests that she might know, as all mothers seem to know, that roughhousing always starts out laughing, but someone ends up crying. Butler4 The mother’s intuition is only confirmed in the third stanza. “The hand that held my wrist/ was battered on one knuckle;/ at every step you missed/ my right ear scraped a buckle.” The buckle scraping the child’s illustrates that the child is a young child, and that the father, in some way, is neglecting the child. The child is clearly encountering pain at the father’s hand, and yet the father continues the waltz. Clearly, the father does nothing to stop the game as soon as the child is encountering pain. This suggests a sort of negligence. One might view the act as abusive, especially with the preceding lines, “the hand that held my wrist/ was battered on one knuckle.” The “battered” knuckle on “the hand” could suggest that the father was in some type of scuffle and might have used the hand as weapon. However, , we must consider Roethke’s background and relationship with his father. Roethke’s father was a gardener, and Otto “built his own house …just in front of the greenhouse, so that he would always be nearby to tend his flowers” (Butterworth). Otto’s job was very physically tasking so it is acceptable for a laborer to have a battered knuckle from a hard day’s work. This removes the idea that the battered knuckle was a result of violence, or suggestive of abuse. It is, rather, Roethke’s acknowledgment of his father’s rough demeanor that he carries over with him from his work. This roughness leads us to “the hand,” which is referred to in the third person. This suggests that the child was either in admiration of his dad's powerful hand, or perhaps in fear of it. The fear can be drawn from the fact that Otto was “a hard taskmaster, demanding perfection” (Butterworth). Roethke sometimes failed to live up to his father’s expectations and would be demoralized for his failure. However, there is a strong sense of admiration. This is drawn from “the life-giving quality in Otto” (Butterworth). Roethke’s father did hard work, work he loved. Roethke respected his father for his work and would often be in the garden helping his father. A Butler5 child would try to stay away from a fearful thing, not join in tasks with the object of fear. Rather than fear, the hand symbolizes the admirable quality the father has with his craft. The interaction continues to be a rough-housing waltz. The fourth stanza creates the final image of both rough-housing and love. “You beat time on my head/ with a palm caked hard by dirt,/ then waltzed me off to bed/ still clinging to your shirt.” As referred to earlier, the hand is still just a labor-roughened hand and is now clearly demonstrated as a gardener’s hand. Although, the image of the “beat time on my head” phrase could create this sense of abuse again. The dad could tap time, or pat time if he was being gentle. He would “beat time” if the son's head was supposed to symbolize a drum. Though, in this poem, it makes more sense that the rough-housing continued, and the "beat time" suggests the vigor of the cadence of the dance. Then the father, like a good parent, takes the child “off to bed/ still clinging to your shirt.” The “clinging” can be two things. It can refer to the past waltzing and that the child was in fear that he would be tossed around and was desperately trying to cling on. On the other hand, it can mean that the child loved his father and Roethke uses this last line to ensure we know this. After reflecting on all the images that showed roughness in the play, and the ambiguity that may have been minor traumatizing actions by the father, the father is still shown in a loving image towards his son. All of these ambiguities arise from differences in meaning that can be taken from the text. The text contains duality that can be interpreted as both positive and negative. The parts taken individually can support either claim and is supported through the poem's structure, words, and phrases. The poem taken as a whole, on the other hand, is an image of a powerful dad, roughhousing with his child, frowned on but accepted by his mother, that leaves us with a snapshot of Butler6 a loving and tender moment between a dad playing with his child. The child remembers the roughness in his memory, but he has a fondness for the interaction. Citation: Blessing, R. A. (1974). Theodore Roethke's Dynamic Vision. London, Indiana University Press. Butterworth, K. (1980). "Theodore (Huebner) Roethke." American Poets Since World War II 5. Fong, B. (1990). "Roethke's 'My Papa's Waltz'." College Literature 17(1): 79-82.