Teacher expectations and student attributes ABSTRACT

advertisement

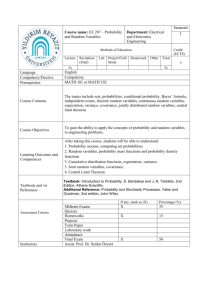

Teacher expectations and student attributes 1 ABSTRACT Background: Teacher expectations have been a fruitful area of psychological research for forty years. Researchers have concentrated on expectations at the individual level, (i.e., expectations for individual students) rather than at the class level. Studies of class level expectations have begun to identify specific factors that make a difference for students. Aims: This study compared types of assessments high and low expectation teachers made of their students’ attributes with teacher expectation and student achievement. Sample: Participants were six high and three low expectation teachers and their 220 students. Methods: Participants were asked to rate their students on characteristics related to attitudes to schoolwork, relationships with others, and home support for school. Results: Contrasting patterns were found for high and low expectation teachers. For high expectation teachers correlations between expectations and all student factors were significant and positive while for low expectation teachers the correlations that were significant were negative. Correlations between student achievement and all student factors were also positive and significant for high expectation teachers while for low expectation teachers only one positive correlation was found. Conclusions: This study adds weight to the argument that class level expectations are important for student learning. Teacher expectation factors appear to relate to differing personal attributes and hence may lead to variance in the instructional and socioemotional climate of the classroom. Teacher expectations and student attributes 2 Teacher expectations and perceptions of student attributes: Is there a relationship? Teacher expectation research began with the seminal work of Robert Rosenthal (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). His aptly named Pygmalion experiment appeared to demonstrate that when teachers expected their students to perform at high levels, they did. This phenomenon became known as the self-fulfilling prophecy effect. Rosenthal suggested that when teachers believed some of their students were very able teachers interacted with them in ways which promoted their academic development. However he did not measure teacher behaviours at the time. Although the methodology that Rosenthal used and his reporting of results were criticized by many (e.g. Snow, 1969; Thorndike, 1968), none questioned the existence or importance of teacher expectations. Teacher behaviours with high and low expectation students Rosenthal’s work led to a plethora of investigations by researchers who began investigating discrepant behaviours teachers might employ with students for whom they had high or low expectations which in turn may result in a self-fulfilling prophecy effect. In a classic study Brophy and Good (1970) observed teacher behaviour in four first grade classrooms with the aim of identifying any discriminatory teacher behaviours with high and low expectation students. They reported evidence teacher behaviours could become behavioural mechanisms for indicating teacher expectations and in turn result in selffulfilling prophecies. For example, they reported teachers required high standards of performance from students for whom they had high expectations and frequently praised such behaviour when it occurred. In contrast teachers accepted poor standards of work from students for whom they had low expectations and far less frequently praised their good performance even though this occurred less often than for students for whom they had high expectations. Later in a review of several other such studies Brophy (1983) isolated 17 Teacher expectations and student attributes 3 teacher behaviours that were utilized differentially with high and low expectation students. For example he reported teachers waited less time for low expectation students to respond to questions than they did for highs, they praised highs more frequently for success than lows, and they rewarded incorrect answers or inappropriate behaviours of lows but not highs. Further, Cooper and Good (1983) showed that teachers tended to interact with highs in public and lows in private. These differential behaviours were used to explain the self-fulfilling prophecy effect of teachers with their individual students. A further implication of teachers’ expectations is that when teachers have high expectations for some students and low for others that this may lead to a halo effect in which teachers also perceive there to be differences in student characteristics. St George (1983) investigated the relationship between teacher perceptions of student characteristics and expectations for student performance. Using a free response approach, five teachers were initially asked to describe the characteristics of 12 previously-taught children. Gender, ethnicity and ability were varied for the students for whom teachers were asked to provide descriptions. Using the teachers’ descriptions 15 seven-point rating scales were developed into a teacher questionnaire in which order and the ends of the positive/negative scale were varied. The pupil attributes were: perseverance, independence, reaction to new work, interest in school work, task concentration, participation in class, confidence, reading, use of English, parent attitudes, home environment, level of disruptiveness, relationships with peers, physical attractiveness and neatness of appearance. Independent raters then unanimously agreed on the positive and negative ends of the scales. Point biserial correlation coefficients were calculated in order to determine relationships between teachers’ perceptions of student attributes and the students’ ethnic group. The results revealed that Maori students in New Zealand were perceived more negatively by their teachers than were New Zealand European students (St. George, 1983) and their teachers also held lower expectations for their achievement. The Teacher expectations and student attributes 4 Maori students in comparison with the New Zealand European counterparts were viewed as coming from home backgrounds that were less favourable for academic development in terms of parent support for education and encouragement for learning in the home. Maori students were further considered to lack interest in schooling and to have limited academic work skills. This study appeared to show a relationship between teachers’ expectations and teacher perceptions of students’ attributes. Teacher factors and the expectation construct More than two decades ago, however, it was recognized that some teachers had considerable expectation effects on their students while most had only small effects (Brophy, 1983). It was further suggested that teachers’ expectations for their classes may well have far more effect on students than the well-researched effects of teachers on individual students (Brophy, 1985). A meta-analysis of 31 teacher behaviours across 136 studies of teacher expectation effects on individual students (Harris & Rosenthal, 1985) showed that those which were of greatest importance in communicating teachers’ expectations were factors such as creating a warm socioemotional climate and including more challenging material in lessons. A positive climate was defined as one in which there were generally positive attitudes, statements or behaviours targeted at students. Including more challenging material was defined as input and was related to teachers who presented more material to students during a lesson and more difficult material. These teacher behaviours which were arguably at the class level, rather than behaviours toward individual students, were of more import in terms of teacher expectation effects than the frequently investigated teacher behaviours towards individual students such as wait time, providing corrective feedback and smiling more at some students. It appeared that teachers’ expectations for their classes of students were worthy of investigation. Yet this area of teacher expectation research continues to be sparsely examined. Teacher expectations and student attributes 5 Indeed following a profusion of teacher expectation studies during the 1970s and 1980s research in this important area declined during the 1990s leading Brophy (1998) to comment that at that time there were only a handful of scholars still actively studying the expectancy construct (Weinstein, Babad and Jussim). Interestingly both Weinstein (Weinstein, 2002; Weinstein & McKown, 1998) and Babad (Babad, 1996, 1998) have turned their focus away from teachers’ expectations of individual students and onto the characteristics of particular teachers, how those characteristics relate to their expectations and implications for students. Studies that investigate teacher expectations of individual students ask the question, what is it about students that mean their teacher may have high or low expectations for them? In contrast studies that examine expectations at a class level, ask the question, what is it about teachers that mean they may have high or low expectations for their students? The current study investigates expectations at a class level, that is, it explores the notion that teachers who have high expectations for all their students differ from teachers who have low expectations for all their students in important ways. In an experimental study Babad and his colleagues (Babad, Inbar, & Rosenthal, 1982) examined the effects of teacher type on how their expectations were operationalized with their students. They identified teachers they called high and low bias. High bias teachers were those who were readily swayed by (false) information about student achievement. As a consequence of the (false) information they received about some students, they interacted with the students in ways which confirmed their expectations rather than acting in accord with the student performance that was actually evident. Low bias teachers, on the other hand were not so readily swayed by the information they were given and continued to interact with students in accordance with the behaviours students exhibited. In later studies (Babad, Bernieri, & Rosenthal, 1989, 1991; Babad & Taylor, 1992) teachers and Grade 5 students viewed 10-second video clips of high bias Israeli teachers interacting with or talking about a Teacher expectations and student attributes 6 high or low expectation student. In these video clips the sound was turned down or the people viewing the videos did not understand Hebrew. Both teachers and ten-year old students were able to identify if the student the high bias teacher was interacting with or talking about was a high or low expectation student. High bias teachers made their expectations of students more salient than did low bias teachers. Teachers who discriminate to a greater or lesser extent between high and low ability students have also been categorized. Brattesani, Weinstein and Marshall (1984) identified such teachers who they called high and low differentiating. High differentiating teachers were those who provided distinctly different work for those students for whom they had high or low expectations and who constantly provided students with messages about their abilities. Low differentiating teachers, on the other hand, did not make ability differences salient in their classrooms. In five separate studies Weinstein and her colleagues gained information from students on the Teacher Treatment Inventory related to how teachers treated high and low ability students (Brattesani et al., 1984; Kuklinski & Weinstein, 2000; Weinstein, Marshall, Sharp, & Botkin, 1987; Weinstein, Marshall, Brattesani, & Middlestadt, 1982; Weinstein & Middlestadt, 1979). Following extensive observations, the results of questionnaires and interviews with students, Weinstein was able to determine specific teacher practices that appeared to be associated with high and low differentiating teachers. For example, high differentiating teachers espoused an entity view of intelligence, they placed children in relatively fixed ability groupings, emphasized performance goals and extrinsic rewards, and frequently implemented negative behaviour management strategies. Hence these teachers viewed ability as fixed; students were viewed as either having ability or not and teachers considered there was little they could do to alter student achievement. Students often sat in ability groups which tended to be stable; there was little room for students to move between groups as their performance altered. Student interaction was discouraged by the Teacher expectations and student attributes 7 teacher. High differentiating teachers frequently contrasted their high and low achievers and made achievement differences known to the students; students were publicly awarded or decried for their performance relative to others and provided with extrinsic rewards such as stars and stickers. Weinstein provided many examples of high differentiating teachers publicly humiliating some students and of managing student behaviour negatively (Weinstein, 2002). In contrast low differentiating teachers held incremental notions of intelligence, used interest based groupings and promoted peer support within these, stressed mastery goals and intrinsic motivation, and developed positive relationships with their students. These teachers took responsibility for student learning; they considered all students could learn given appropriate support by the teacher. They viewed student mistakes as opportunities for learning and as a reflection of their teaching, that is, that they needed to find different ways to teach a concept to students when they had difficulty. Students were seated in mixed ability groupings and were actively encouraged to help each other. Indeed although these teachers also awarded students with points these were given for group efforts and group support and cooperation, rather than for individual efforts. In these classes the emphasis was on individual progress and the achievement in relation to individual goals. Low differentiating teachers formed positive relationships with their students and in turn encouraged their students to form positive relationships with each other. In classes of high differentiating teachers, expectations explained 14% of the variance in student end of year achievement whereas in classes of low differentiating teachers only 3% of the variance in student end of year achievement could be explained by teachers’ expectations (Brattesani et al., 1984). This is a marked difference and points to teacher factors playing a considerable part in the portrayal of teacher expectations. High and low expectation teachers Teacher expectations and student attributes 8 Recently Rubie-Davies and her colleagues (Rubie-Davies, Hattie, Townsend, & Hamilton, 2007) have demonstrated that some teachers have expectations at the class level, that is their expectations (high or low) are for all students. This conception of expectations had not previously been investigated. One month into the academic year, a group of teachers (n = 24) were asked to decide the reading level they expected each of their students to achieve by the end of the year on a seven-point scale from very much below average to very much above average. Teacher expectations were then compared with student achievement at the beginning of the year on the same seven-point scale based on running record results collected by the researcher. Results were aggregated across each class. Of the original sample of 24 teachers, six teachers were found to have expectations for end of year performance that were significantly above their students’ achievement at the beginning of the year while three teachers had expectations that were significantly below students’ performance at the time. Students with high expectation teachers (HiEx) made much greater progress in reading over one year (mean effect size across all classes: d = 1.01) than students of low expectation teachers (LoEx) (mean effect size across all classes, d = .05). Student self-perceptions in the classes of high and low expectation teachers were also measured. Using appropriate subscales of the SDQ-1 (Marsh, 1990) it was found that while the self-perceptions in maths and reading of students with HiEx teachers improved across the year of the study, those of students with LoEx teachers declined considerably. Moreover, students seemed to be aware of their teachers’ expectations because when asked to rate on the same five-point scale the statements: my teacher thinks I am good at reading; my teacher thinks I am good at maths the same pattern was evident as for the academic self-perceptions (Rubie-Davies, 2006). In a further study HiEx and LoEx teachers were interviewed and contrasting patterns were shown in their pedagogical beliefs and self-reported teaching practices (Rubie-Davies, Teacher expectations and student attributes 9 in press). Classroom observations confirmed the interview findings of teachers’ self-reported practices (Rubie-Davies, 2007). Briefly, HiEx teachers had students working in mixed ability groups, promoted student autonomy in learning activities, carefully explained new concepts, provided students with clear feedback, managed behaviour positively and asked large numbers of open questions. LoEx teachers maintained within-class ability groups, directed student learning experiences, frequently gave procedural directions, reacted negatively to student misbehaviour, and asked mostly closed questions. It appears there are particular types of teachers who make a large difference to student learning depending on their expectations. Other teachers have more moderate effects. Brophy (1985) claimed two decades ago that whole class teacher expectation effects were likely to be greater than expectation effects for individual students and yet class level expectations have still only been investigated in a small number of studies. The current study Research into whole class expectation effects has concentrated on investigating student achievement and perceptions, and teachers’ beliefs and practices; there do not appear to be any studies that have explored the relationship between teachers’ expectations at the class level and how teachers perceive their students’ attributes. As noted earlier one study (St. George, 1983) did find a relationship between teachers’ expectations and perceptions of Maori and New Zealand European students. Hence it is of interest to determine whether teachers who have high expectations for all their students’ academic progress have similarly positive perceptions of their students’ attitudes to school work and of family support for education. The aim of the current study was to further extend understanding of the characteristics of high and low expectation teachers by examining how they perceived a range of student attributes. Whether high expectation teachers would have positive perceptions of their students and their attributes and low expectation teachers the opposite Teacher expectations and student attributes 10 was of interest. How teachers perceive students is important since perceptions can lead to altering pedagogy in line with beliefs about students (Rubie-Davies, Hattie, & Hamilton, 2006). If teachers’ class level expectations align with their perceptions of students this may have important consequences for student learning. The research questions were: How do teachers’ expectations relate to perceptions of student attitudes to schooling and, how do teacher perceptions of students’ attitudes to schooling relate to student achievement? Method Participants. The participants in this study were the six primary school HiEx teachers and the three LoEx teachers who had participated in previous investigations (Rubie-Davies, 2006, 2007, in press). As outlined above these were teachers whose expectations were either significantly above (HiEx) or significantly below (LoEx) the reading achievement of their students as demonstrated by running record results. Further analyses at the ability group level (high, average and low) showed that expectations were indeed for all students of both HiEx and LoEx teachers (Rubie-Davies, 2006). The students of high expectation teachers made substantial progress across the year of the initial study (effect size gains across the six classrooms were d = .50, .73, .86, 1.27, 1.28, 1.44) while those with low expectation teachers made considerably less progress (d = .20, -.02, -.03). It is of note that the reading achievement of the students with high expectation teachers on a 1-7 scale was significantly below that of students with low expectation teachers at the beginning of the year (M = 3.52 (HiEx) and 4.69 (LoEx), p < .001). Table 1 provides details of the high and low expectation teachers on which this study is based. One interesting revelation from this table is that the two high expectation teachers in low decile schools had more teaching experience than any other teachers. In contrast there was a trend for the low expectation teachers to have less experience than the highs. Teacher expectations and student attributes 11 __________________________ Insert Table 1 about here __________________________ Measures. The six HiEx teachers (135 students) and three LoEx teachers (75 students) who participated in the current study rated students’ attitudes to their schoolwork, their relationships with others and their home support. The scale developed by the researcher was based on the scale used by St. George (1983). However, some changes were made in order to reflect current teacher terminology and understandings. For example, ‘cognitive engagement’ replaced ‘task concentration’ and ‘peer relationships’ replaced ‘relations with classmates’. The following characteristics were included in the scale: perseverance, independence, reaction to new work, interest in school work, cognitive engagement, participation in class, motivation, confidence, self-esteem, classroom behaviour, peer relationships, teacher relationships, parent attitudes to school, home environment, homework completion. Procedure. The teachers completed their ratings of their students onto a computer using the Smartadata program (Davies, 2007) which automatically uploaded the data into the author’s database thus avoiding any potential data entry errors. Using a 7 point Likert scale where, for example, 1=well below average; 3=a little below average; 6=moderately above average, each teacher rated every student in his/her class on the characteristics listed above. Teachers could assign a particular rating to specific students and across their class as many times as they thought appropriate for their students; there were no restrictions on allocating ratings. This method gave teachers freedom in assigning their ratings and was then used to establish any associations between teachers’ expectations (high or low) and positive or negative perceptions of student attitudes. The results of the teacher ratings were then aggregated by teacher type (HiEx or LoEx teacher) in order to perform the statistical analyses outlined below. Teacher expectations and student attributes 12 Results Teacher expectations and perceptions of students Relationships between teachers’ expectations and their perceptions of students’ attitudes and characteristics were calculated using Pearson correlations (see Table 2). Correlations between student achievement and teachers’ perceptions of student attitudes are also included in Table 2. For HiEx teachers, there was a statistically significant and positive correlation between teachers’ perceptions of all student attitudes and their expectations (p<.001 for all variables). Teacher perceptions of perseverance, independence, reaction to new work, interest in school work, participation in class, motivation, confidence, self-esteem, classroom behaviour, relationships with peers, relationships with the teacher, parent attitudes to school, home environment and completion of homework were moderately correlated with teachers’ expectations for their students. The correlation between teacher perceptions of student engagement and teachers’ expectations was strong. The high expectation teachers had very positive views of their students that reflected their positive expectations. The pattern was quite different for LoEx teachers. There were fewer significant correlations between teachers’ perceptions of student attitudes and teachers’ expectations. Where there was a statistically significant correlation this was small and negative. Teacher expectations were correlated negatively with interest in school work, motivation, classroom behaviour, peer relationships, teacher relationships and homework completion. This means that while teachers’ expectations for their students were low their perceptions of some student attributes were not similarly low. Hence the expectations of this group of teachers did not relate to their perceptions of some student characteristics. The teachers appeared to believe that their students tried hard (interest in school work and motivation), behaved in class Teacher expectations and student attributes 13 (classroom behaviour) and related well to others (peer relationships and teacher relationships) even though their expectations for student achievement were low. _____________________________________________ Insert Table 2 about here ______________________________________________ Student achievement and teacher perceptions Similarly in the classes of HiEx teachers, there were positive and statistically significant correlations between student achievement and teacher perceptions of student attributes (p<.001 for all variables). These correlations were moderate for perseverance, independence, reaction to new work, interest in school work, cognitive engagement, participation in class, motivation, confidence, self-esteem, parent attitudes to school, home environment and small for classroom behaviour, relationships with peers, relationships with teachers, homework completion. It seems high expectation teachers perceived student attributes positively and in line with achievement. In other words the more successful students were the more positively high expectation teachers viewed their attributes. For LoEx teachers the only statistically significant correlation was small and was between student achievement and teachers’ perceptions of student motivation. Hence low expectation teachers perceived that student achievement was related to student motivation. There were no other student attributes that were associated with student achievement for this group of teachers. Discussion This study builds the argument that high and low expectation teachers have distinguishing characteristics. There was a differing relationship between teachers’ expectations and perceptions of students’ attributes depending on whether teachers were high or low expectation. For high expectation teachers the association between expectations and perceptions of student characteristics was positive and strong. Positive relationships might be Teacher expectations and student attributes 14 anticipated since positive student attitudes are often associated with success at school (Patrick, Anderman, & Ryan, 2002). When teachers recognize such attributes in their students they are more likely to foster positive student attitudes and social relationships leading to enhanced motivation, engagement and success in school (Ryan & Patrick, 2001). Students in the classes of high expectation teachers made large gains in learning over one year and improved their self-perceptions (Rubie-Davies, 2006); it is possible that their learning was enhanced because teachers viewed their attributes positively as well as having high expectations for them. The association for low expectation teachers between their expectations and their perceptions of student attributes was weaker and negative. This suggests low expectation teachers viewed the relationship between their expectations for student achievement and perceptions of student characteristics differently. While their perceptions of student progress were below what might have been anticipated they did not necessarily view student attributes negatively. However, in the unsupportive classroom environments found in low expectation classrooms (Rubie-Davies, 2007, in press) students may be receiving confusing messages from teachers. Teachers may be providing positive messages about some student characteristics but negative messages about their expectations for student achievement. While the teachers’ expectations of their students were low it seems they did give them credit for trying hard, behaving well in class and relating well to others. Implications of teacher expectations and perceptions of students High expectation teachers build positive learning and socioemotional environments in their classrooms (Rubie-Davies, 2005, 2007). It appears their perceptions of student attitudes are also overwhelmingly positive. High expectation teachers are affirmative in their assessments of students’ attitudes to schoolwork, student relationships with others and the support students receive from their families. There is an increasing awareness of the role of teacher caring in fostering student achievement (Patrick et al., 2002; Wentzel, 1997). It would Teacher expectations and student attributes 15 seem that not only do high expectation teachers develop a positive classroom community but that their attitudes towards their students show that they view student characteristics optimistically. This suggests a level of teacher care and respect for students. Low expectation teachers on the other hand viewed student achievement negatively. Their expectations for student achievement were below actual attainment. However they perceived student interest in school work, motivation, behaviour in class and completion of homework more positively. These are attitudes that pertain to student effort. One implication could be that while low expectation teachers view achievement as low they perceive that students are trying hard. This would suggest an entity view of intelligence, a perspective which researchers are increasingly showing is detrimental to student learning and achievement (Dweck, Mangels, & Good, 2004; Weinstein, 2002). When teachers hold an entity view of intelligence they tend to believe that they can have little impact on student learning; what students can learn is pre-determined. On the other hand teachers who have an incremental notion of intelligence believe that all children can learn given appropriate support and opportunity to learn (Dweck, 2000). Students appear to be well aware of their teachers’ expectations and attitudes towards them since they can provide specific examples and critical incidents that demonstrate their understanding of teacher messages (Weinstein, 1993). It would seem possible therefore that students with high expectation teachers are aware of their teachers’ positive views not only of their achievement but also of their behaviour, interest and motivation in class. When students are consistently being given encouraging messages from their teachers this may be one explanation for why student self-perception improved across a year in the classes of high expectation teachers (Rubie-Davies, 2006). On the other hand students with low expectation teachers may be aware of the very different messages their teachers portray which may affect their self-perceptions negatively rather than positively. Teacher expectations and student attributes 16 Understanding relationships between student achievement and attributes There was a similar pattern for relationships between student achievement in reading and how teachers perceived students’ qualities. Again for high expectation teachers this association was strong. There was a positive correlation between all teacher perceptions of student attitudes and students’ achievement. For low expectation teachers, the relationship was very weak. Only cognitive engagement was associated by them with actual achievement and even then the correlation was low. It appears mostly that low expectation teachers do not perceive a relationship between students’ achievement and personal characteristics. They may have less understanding of their students than high expectation teachers. It may be that low expectation teachers held inaccurate judgments of their students’ attainment since their expectations were well below student achievement. It is less likely that low expectation teachers would perceive that student achievement would decline after being in their classes for a year. It would seem probable that teachers would perceive a relationship between students’ attitudes to schoolwork, completion of homework and student achievement; this was found for high expectation teachers but not for lows. However, teachers were not asked about why they set their expectations at particular levels or why they rated student attributes as they did and so this is a limitation of the study. Conclusions and future directions The current research is important in advancing knowledge about high and low expectation teachers. It seems that expectations for intact classes may indeed be a more powerful mediator of self-fulfilling prophecy effect than expectations for individuals within classes (Brophy, 1985), but the focus has remained on expectations for individuals. Research has sought to determine student characteristics that lead teachers to interact in particular ways towards particular students. However, Babad, (1998), Weinstein (2002) and now RubieDavies and colleagues (Rubie-Davies et al., 2007) have shown that a future direction for Teacher expectations and student attributes 17 teacher expectation research is to more closely examine what it is about particular types of teachers (rather than students) that lead to differential interaction patterns with whole classes of students. It would seem that some teachers have important positive effects on student learning while other teachers may impact student learning to a lesser extent or, indeed, negatively. It is of note that a recent study (McKown & Weinstein, in press) has shown that high differentiating teachers have much lower expectations for African-American and Hispanic students than they do for White students with similar achievement. Low differentiating teachers’ expectations were based on student achievement, not ethnicity. This is further evidence that teacher rather than student characteristics are important and worthy of future research. While the current study included only a small number of teachers it does provide further evidence of the need to shift attention in teacher expectation investigations to whole class scenarios. Further expectation studies at the class level with larger numbers of participants will facilitate the generalizabilty of results. Such research is important as it could lead to increased understandings of differing types of teachers and allow interventions which foster the beliefs and practices of high expectation teachers among all teachers. This could in turn lead to improved learning opportunities for students in supportive classroom environments. Questions about the implications of teacher expectations, particularly at the class level, are debates about equality in education, about enhancing student learning. In endeavouring to unravel the attributes of high expectation teachers that make positive differences for students the aim is to ensure high quality teaching for all students. Teacher expectations and student attributes 18 References Babad, E. (1996). How high is "high inference"? Within classroom differences in students' perceptions of classroom interaction. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 31, 1-9. Babad, E. (1998). Preferential affect: The crux of the teacher expectancy issue. In J. Brophy (Ed.), Advances in research on teaching: Expectations in the classroom (Vol. 7, pp. 183-214). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Babad, E., Bernieri, F., & Rosenthal, R. (1989). Nonverbal communication and leakage in the behavior of biased and unbiased teachers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 89-94. Babad, E., Bernieri, F., & Rosenthal, R. (1991). Students as judges of teachers' verbal and nonverbal behavior. American Educational Research Journal, 28, 211-234. Babad, E., Inbar, J., & Rosenthal, R. (1982). Pygmalion, Galatea and the Golem: Investigations of biased and unbiased teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 459-474. Babad, E., & Taylor, P. B. (1992). Transparency of teacher expectancies across language, cultural boundaries. Journal of Educational Research, 86, 120-125. Brattesani, K. A., Weinstein, R. S., & Marshall, H. H. (1984). Student perceptions of differential teacher treatment as moderators of teacher expectation effects. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 236-247. Brophy, J. E. (1983). Research on the self-fulfilling prophecy and teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75, 631-661. Brophy, J. E. (1985). Teacher-student interaction. In J. B. Dusek (Ed.), Teacher expectancies (pp. 303 - 328). Hillsdale, N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum. Brophy, J. E. (1998). Introduction. In J. E. Brophy (Ed.), Advances in Research on Teaching (Vol. 7, pp. ix-xvii). Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press Inc. Brophy, J. E., & Good, T. L. (1970). Teachers' communication of differential expectations for children's classroom performance: Some behavioral data. Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 365-374. Cooper, H. M., & Good, T. L. (1983). Pygmalion grows up: Studies in the expectation communication process. New York: Longman. Davies, J. I. (2007). Smartadata (Personal Edition) [Computer software]. Auckland: Smartadata Ltd. Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self theories: Their role in motivation, personality and development. Philadelphia: Psychology Press. Dweck, C. S., Mangels, J. A., & Good, C. (2004). Motivational effects on attention, cognition, and performance. In D. Y. Dai & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Motivation, emotion, and cognition: integrative perspectives on intellectual functioning and development (pp. 41-56). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Harris, M. J., & Rosenthal, R. (1985). Mediation of interpersonal expectancy effects: 31 meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 97, 363-386. Kuklinski, M. R., & Weinstein, R. S. (2000). Classroom and grade level differences in the stability of teacher expectations and perceived differential treatment. Learning Environments Research, 3, 1-34. Marsh, H. W. (1990). Self Description Questionnaire - 1 manual. Campbelltown, N.S.W., Australia: University of Western Sydney. McKown, C., & Weinstein, R. S. (2008). Teacher expectations, classroom context and the achievement gap. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 235-261. Teacher expectations and student attributes 19 Patrick, H., Anderman, L. H., & Ryan, A. M. (2002). Social motivation and the classroom social environment. In C. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 85-108). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectation and pupils' intellectual development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2005, December). Exploring class level teacher expectations and pedagogical beliefs. Paper presented at the New Zealand Association for Research in Education Annual Conference, Dunedin, New Zealand. Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2006). Teacher expectations and student self-perceptions: Exploring relationships. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 537-552. Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2007). Classroom interactions: Exploring the practices of high and low expectation teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 289-306. Rubie-Davies, C. M. (in press). Teacher beliefs and expectations: Relationships with student learning. In C. M. Rubie-Davies & C. Rawlinson (Eds.), Challenging thinking about teaching and learning. Haupaugge, NY: Nova. Rubie-Davies, C. M., Hattie, J., & Hamilton, R. (2006). Expecting the best for students: Teacher expectations and academic outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 429-444. Rubie-Davies, C. M., Hattie, J., Townsend, M. A. R., & Hamilton, R. J. (2007). Aiming high: Teachers and their students. In V. N. Galwye (Ed.), Progress in Educational Psychology Research (pp. 65-91). Hauppauge, NY: Nova. Ryan, A. M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents' motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 437-460. Snow, R. E. (1969). Unfinished Pygmalion [Review of Pygmalion in the classroom]. Contemporary Psychology, 14, 197-199. St. George, A. (1983). Teacher expectations and perceptions of Polynesian and Pakeha pupils and the relationship to classroom behaviour and school achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 53, 48-59. Thorndike, R. L. (1968). Review of the book "Pygmalion in the classroom". American Educational Research Journal, 5, 708-711. Weinstein, R. S. (1993). Children's knowledge of differential treatment in school: Implications for motivation. In T. M. Tomlinson (Ed.), Motivating students to learn: Overcoming barriers to high achievement (pp. 197-224). Berkeley, CA: McCutchan. Weinstein, R. S. (2002). Reaching higher: The power of expectations in schooling. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Weinstein, R. S., Marshall, H., Sharp, L., & Botkin, M. (1987). Pygmalion and the student: Age and classroom differences in children's awareness of teacher expectations. Child Development, 58, 1079-1093. Weinstein, R. S., Marshall, H. H., Brattesani, K. A., & Middlestadt, S. E. (1982). Student perceptions of differential teacher treatment in open and traditional classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 678-692. Weinstein, R. S., & McKown, C. (1998). Expectancy effects in "context": Listening to the voices of students and teachers. In J. Brophy (Ed.), Advances in Research on Teaching. Expectations in the Classroom (Vol. 7, pp. 215-242). Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press. Weinstein, R. S., & Middlestadt, S. E. (1979). Student perceptions of teacher interactions with male high and low achievers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 421-431. Wentzel, K. R. (1997). Student motivation in middle school: The role of perceived pedagogical caring. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 411-419. Teacher expectations and student attributes 20 Table 1 Demographic Details for High and Low Expectation Teachers Teacher Expectation Socioeconomic Area Class Level Teaching Service HiEx Low Junior 25 HiEx High Senior 1 HiEx High Junior 5 HiEx High Junior 7 HiEx High Senior 6 HiEx Low Junior 25 LoEx Low Senior 4 LoEx High Senior 8 LoEx High Junior 7 Group Teacher expectations and student attributes 21 Table 2 Correlations Between Teacher Expectation, Student Achievement and Perception of Student Characteristics High Expectation Teachers Low Expectation Teachers Student Teacher Student Teacher Student Characteristics Expectation Achievement Expectation Achievement Perseverance .62*** .42*** -.17 .12 Independence .64*** .50*** -.07 .21 Reaction to new work .66*** .49*** -.11 .13 Interest in school .60*** .43*** -.23* .08 .70*** .56*** .03 .25* Participation in class .68*** .49*** -.11 .14 Motivation .64*** .44*** -.33** .02 Confidence .65*** .55*** -.11 .11 Self-esteem .65*** .51*** .08 .21 Classroom behaviour .40*** .28*** -.39*** -.12 Relationships with .44*** .32*** -.29** -.08 .56*** .38*** -.33** -.08 .57*** .42*** -.11 .14 work Cognitive Engagement peers Relationships with teachers Parent attitudes Teacher expectations and student attributes 22 Home environment .61*** .46*** .18 .17 Homework .55*** .39*** -.31** .06 completion