Rhetorical Analysis

advertisement

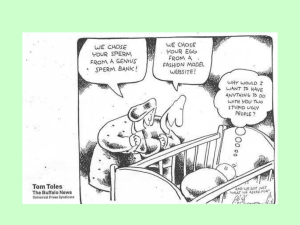

John Anderson Rhetorical Analysis Mr. Negley English 1010 3A Abortion has been a hot topic of controversy in our country for decades. Despite the Supreme Court’s stamp of approval in the 1973 case Roe v. Wade, the subject of woman’s rights and those of the embryo are still hotly debate. Since most people agree that human beings who have done nothing wrong should not have their lives terminated, most of the controversy rests around the subject of when exactly and embryo should be considered a human. While some believe that an embryo is human from conception, others argue that a bundle of embryonic cells cannot be placed on the same level as a 300 trillion cell human being. In an effort to formulate a more informed opinion on the subject of the beginning of human life, I have researched and discovered two articles with opposing viewpoints. The first, a submission to the website Patheos.com, is written by Bob Seidensticker, and argues that there is a spectrum to the humanity of a developing fetus, marked by developmental milestones like a beating heart or a functioning brain. On the other hand, Robert Reville makes the claim that an embryo is a human being from the moment of conception. My aim in this essay is not to choose who is correct, but rather to analyze which author more effectively utilizes rhetorical appeals to convince their audience of their argument. By using a more academic writing style, and by relying upon his own credibility, Reville is ultimately more successful than Seidensticker in his attempt to persuade his readers. William Reville has a PhD in Biochemistry, and is currently a professor of biochemistry at University College Cork in Ireland. Aside from editing several academic books, Reville wrote his own book entitled, “Understanding the Natural World” in 1999. Aside from writing books, Reville also writes scientific editorials for the Irish Times. One such piece, “Under the Microscope” deals with the topic of when human life actually begins. According to the selfpublished demographic statistics of the Irish Times the majority of the readers of the times, and therefore the demographic to whom the article is likely directed are white men and women who are educated, employed, and typically over the age of thirty. William Reville begins his article by stating the debate of exactly when a developing embryo becomes “human” is a serious topic that has potential to influence many more facets of life than the availability of abortion. He is quick to make the claim that the scientific evidence indicates that an embryo is a human from conception. He supports this claim by comparing embryonic development to human development in later stages of life such as puberty; no one claims a preadolescent is not yet worthy of being called a human. Reville utilizes his biochemistry background to present a very scientific and secular case for the humanity of an embryo by describing the process by which an embryo develops into a fetus and then a baby. Reville concludes the article by stating that if we determine that an embryo is in fact a human, it is entitled to the same protection and rights that any other human has. The first rhetorical appeal the Reville utilizes is a very scientific tone of voice in the article. For example, revile states, “The story of human life begins at conception when a sperm cell from the father fuses with an egg cell from the mother to produce a unique new entity called a zygote.” This single quote gives a very accurate sampling for the tone of the rest of the article. Reville uses this specific tone in order to build his own credibility. Being a PhD of biochemistry, Reville has a broad knowledge of the science behind human development, and this scientific approach makes the reader trust the author because we appeal to his supposed greater knowledge on the subject. Also, Reville uses bold text throughout the article to place emphasis on certain ideas. Terms such as “human” and “human life” are always bolded in the article. This is done quite intentionally. Because most of us have such a high level of respect and reverence for human life, and because the main argument of the article is that, if in fact an embryo is considered to be a human, we have a duty to protect human life. These bolded terms keep the reader focused on the value of human life, and therefore more inclined to agree that an embryo should be protected. Robert Seidensticker graduated from MIT with a doctorate in computer technology. He has worked for major companies such as IBM and Microsoft. Currently, Seidensticker supports himself through writing computer code independently. Seidensticker has also become a part time writer, and has posted hundreds of articles to the popular religion forum patheos.com. I selected one of his articles, entitled “Five Intuitive Pro-Choice Arguments” to contrast with Reville’s article. According to the website patheos.com, the majority of its readers are between the ages of 22 and 35, with a surprising 73 percent majority being female readers. Because the website features articles from atheism to fundamental Islam, the readers of the site are likely to be well versed with a variety of religious perspectives. Seidensticker starts his article by making the claim that the issue of the beginning of life is as complex as life itself. He argues in his beginning paragraphs that rather than a black and white dividing line, there is a spectrum to the humanity of the developing embry. Seidensticker then goes on to list his five reasons for his beliefs. The reasons he lists are organized by bolded titles, to make the article quick and easy to digest. After his argument, Seidensticker acknowledges that while it may be possible to scientifically claim that an embryo is in fact human, the fact of the matter is that we, as human beings, do not actually put the embryo on the same level as a fully formed human baby. Seidensticker first utilizes emotional appeals as opposed to a more logical approach. In his introduction, Seidensticker states that, “since emotion plays such a strong part of the discussion, I’ll set aside intellectual arguments and focus instead on emotional ones.” By avoiding the science of the topic of the beginning of life, Seidiensticker is able to focus on the much more easily manipulated. This way, Seidensticker can present an argument that cannot be easily refuted because emotions are subjective. Next, Seidensticker utilizes differentiated sections of text to create a very fast-paced article. Every two or three paragraphs, Seidensticker adds a section title in bold like, “1. Child vs. Embryos.” Seidensticker does this to move through the article very quickly by avoiding spending time on topic transitions. The use of this technique is that the article does not get bogged down in the details. Most people reading the article are not developmental scientists, and would therefore lose interest in an article that is overly explorative of the details of human development. Instead, Seidensticker is able to focus on his main arguments and keep his readers engaged and interested. Both articles present very different tones and styles of argument. Ultimately, Reville’s logical and scientific approach is more effective than the informal and causal writing style of Seidensticker. For example, while Seidensticker is saying things like, “I’ll set aside intellectual arguments and focus instead on emotional ones,” Reville is making statements such as, “I believe that a strong case, consistent with science, can be made for the full humanity of the embryo.” This clear dichotomy causes a reader to find Reville’s article to be more trustworthy and reliable due to a more professional nature. Again, this more logical approach is seen when Reville begins to explain the science of conception and the beginning of life stating, “The story of human life begins at conception when a sperm cell from the father fuses with an egg cell from the mother to produce a unique new entity called a zygote.” Scientific statements such as this are far more effective than Seidensticker’s obscure and random statements like, “Which would be more horrible to watch: a woman swallowing a pill of Plan B or a cow going through a slaughterhouse?” Clearly, Reville is much more on point in terms of effective argumentation. Another reason that Reville presents a more powerful argument than seidensticker is his own ethos. As stated at the bottom of his article, Reville is a “is associate professor of biochemistry and public awareness of science officer at UCC.” Reville’s background as a highly educated scientist gives credit to his scientific arguments about the beginning of life. On the other hand, Steidensticker makes no note of his credentials in his essay. This is likely because he is entirely lacking in applicable credibility. A little research reveals that Seidensticker was a big shot in the world of computer technology. While no doubt and intellectual man, his academic background is not such grant his argument and more validity than yours or mine would have. Originally, I set out to determine whether I felt abortion ought to be legalized or not, but throughout my investigation I realized that the real issue is not abortion, but rather when human life begins exactly. This issue is so critical because it applies to much more than abortion. If we accept that human life begins at conception, then one could argue that all women who can bear children should not be allowed to consume alcohol because of the risks it poses to the human developing in an unknown pregnancy. The debate of human life is impactful and much more far-reaching than its influence on the legalization of abortion.