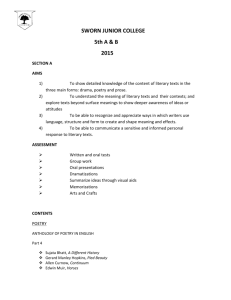

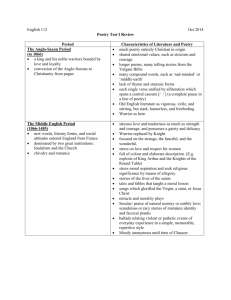

History of English Literature ENG-402

advertisement