Thursday, June 20, 2013 National Research Council Symposium

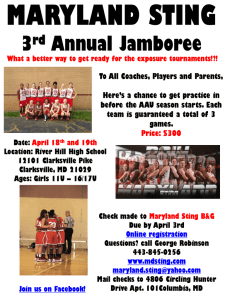

advertisement

Thursday, June 20, 2013 National Research Council Symposium “Defining Maryland as the STEM Capital” Remarks of USM Chancellor William “Brit” Kirwan Good afternoon. It is a pleasure to be with you today. The topic we will address— Defining Maryland as the STEM Capital—is incredibly timely. As the national economy begins to gather momentum and recover from the protracted period of recession, it is simply a truism that innovation, discover, and technology—the elements that define the STEM disciplines—will be the drivers. The possibility exists to position Maryland at the forefront of this next wave of growth, with our research universities leading the way. There is no question we have a number of strengths to support this, but we must recognize our challenges and act aggressively to overcome them. First—on the plus side—we all recognize that Maryland is in a very favorable position. Just last month, the New York Times published an article noting that—according to the U.S. Census Bureau—Maryland is the third best educated state in the nation, behind only Massachusetts and Colorado in terms the highest share of bachelor’s degree holders. And in terms of advanced degrees, Maryland ranks second to Massachusetts. Several major private companies have a significant Maryland presence: Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Verizon, and others. We have one of the largest clusters of biotechnology companies in the U.S. And we are home to more than 50 federal agencies and research facilities: the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), National Security Agency (NSA), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and many others. All of these elements have combined to give Maryland an enormous research enterprise. In fact, Maryland ranks second in total federal obligations for R&D—and first on a per-capita basis. The state is third in R&D intensity and fourth in R&D performed at universities and colleges. Between the USM’s three research universities—College Park, Baltimore, and Baltimore County—and Johns Hopkins University, we can claim $3.5 billion in annual academic R&D. 2 That’s the good news. Here’s the bad news: Maryland ranks 28th in economic gain from R&D. As a state we are simply not doing enough to promote opportunities for licensing and commercialization of intellectual property, coming up short in providing proof-of-concept funding and seed funding, and not aggressively linking university research labs with technology-based companies. These same shortcomings are highlighted in the Milken Institute’s State Technology and Science Index 2012, which tracks and evaluates every state's tech and science capabilities and their success at converting those assets into companies and highpaying jobs. Overall, Maryland ranks second in the nation, doing well in almost every category: second in Research and Development Inputs, second in Human Capital Investment, second in Technology and Science Workforce, and fourth in Technology concentration and dynamism. The only area where Maryland does not rank in the top five is the category of Risk Capital and Entrepreneurial Infrastructure, which specifically measures the success rate of converting research into commercially viable products and services. This is an area the report noted that Maryland has “consistently underperformed.” Or consider the Kauffman Foundation study noting that about half of the nation’s tech startups were established in the same state where the founders received their education. But for Maryland, that numbers down around 15 percent. This goes hand-in-hand with a Boston Federal Reserve study showing Maryland slipping out of the top ten and all the way down to 27th in terms of its ability to keep its graduates in state. We simply must keep more of our graduate—and their startups—here. So those are the challenges we are facing. And I do want to note that working together, leaders in Annapolis, the business community, and our public and private universities, have been attaching this challenge aggressively. Two years ago, with strong support from both the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins, Governor Martin O’Malley and the General Assembly launched the $84 million Maryland Venture Fund to support startups and help fill the existing venture capital gap. Last year the same team supported the creation of the Maryland Innovation Initiative to help move discoveries from academia into the marketplace more quickly. These two state programs will work in tandem—providing the “push” from the lab and the “pull” of the marketplace—allowing Maryland to take better advantage of its technical and scientific talent. The USM’s new strategic plan made advancing Maryland's competitiveness in the innovation economy a key goal. To advance that goal the Board of Regents established the Committee on Economic Development and Technology Commercialization—the first new standing committee created in over a decade—to provide oversight and support for campus based technology transfer and commercialization activities. In order to encourage and reward a more 3 entrepreneurial culture within our faculty, the Board also expanded the criteria for promotion and tenure to include activities involving the creation of intellectual property and technology transfer. And we initiated a new, extensive partnership between our two largest research institutions, the University of Maryland, College Park (UMCP) and the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB). This collaborative relationship—University of Maryland: MPowering the State—is designed to leverage the resources of these two significant and complimentary research universities to advance the quality for the two institutions, expand their research portfolios and boost technology transfer, and commercialization of intellectual property. While less than a year old, this new collaborative relationship is already producing significant results. Finally, under MPowering the State, we have launched University of Maryland Ventures (UMV), which brings under one administrative structure a single director for the technology transfer and commercialization activities on the two campuses. Each campus had components of a successful tech transfer operation but neither had the full suite of services. Now we have that. Essentially what we are doing with all these efforts is improving the state’s science and tech ecosystem in a manner that will allow Maryland’s innovation economy to thrive. I am sure many of you have read The Rainforest: The Secret to Building the Next Silicon Valley by Victor Hwang and Greg Horowitt. In this book, the authors look to explain the nature of innovation ecosystems: human networks that generate extraordinary creativity and output. They argue that these ecosystems—or “Rainforests”—can only thrive when certain cultural behaviors unlock human potential. Theses ecosystem are not so much “created”—you cannot replicate Silicon Valley—as they are grown, nurtured, and sustained. As Victor Hwang puts it, “talent, ideas, and capital are the nutrients moving through this biological system, and the system becomes more productive the faster these nutrients are allowed to flow.” In a moment I will be asking our panelists for some of the ideas they may have to enhance Maryland’s science and technology ecosystem, but I’d like to get the conversation started by noting a few ideas of my own. But first, let me make two quick points: First, even through Maryland lags in commercializing research, it is still a huge part of the state’s economy. Even if we had no tech transfer at all, our success still funds professors, students, and our universities, grows the economy, and makes Maryland more competitive overall. Second, the biggest tech transfer event happens every year and has nothing to do with patents; we call it “graduation”. The USM alone awarded a record number of degrees this year—34,500—including two-thirds of all degrees awarded in the STEM fields. 4 Now . . . let me quickly share a few thoughts on ways to nurture our science and tech ecosystem Given that commercialization efforts for many new technologies often die on the vine for lack of funding to conduct a market study or pay for patent costs, it might make sense to change the SBIR program to empower researcher to deploy up to 5 percent of a federal research contract or grant for such commercialization purposes. This would not be a requirement, just an option. It would not increase the costs of the grants. Researchers would be held accountable for use of the 5 percent as part of the normal reporting process, so no new bureaucracy would need to be developed. And, unlike the very small federal technology commercialization initiatives—i6 challenge was only $5 million nationwide—this would be applied to literally billions of federal research grants and contracts. The National Commission of Innovation and Entrepreneurship has hinted at such a transformative and scalable program, but I am not aware of any formal suggestion to OMB. Universities currently allow faculty to consult with industry, but often times industry does not know which faculty have the expertise they are looking for, and often faculty don’t know how to go about finding corporations interested in their knowledge. In addition, the faculty members usually can’t bring back any work to the university or support grad student with the consulting work. In the UK and Australia, universities have flipped this model around and have formal consulting practices where the university organizes a faculty consulting practice, making knowledge transfer more efficient and providing support for grad students in the process. Some American universities, such as Purdue, are experimenting with this model and Maryland universities should also examine allowing universities to create formal consulting practices for industry: A Knowledge Transfer Program. Right now, a myriad of laws and missions prevent federal labs from being entrepreneurial. For example, federal labs in Maryland do somewhere around $12 billion annually in internal research and NIH is the world’s largest bio-medical institution. But you don’t see start ups in Bethesda. We need Congress to create a federal lab technology intermediary—similar to TEDCO on the state level—that would be a quasi-governmental technology intermediary or entrepreneur in residence that could take on the business of tech transfer. Finally, I would suggest that Maryland is ripe for a much more significant global research presence. We could bring more international firms to the Baltimore/Washington region given our robust R&D, the proximity of foreign embassies, and our international airports. As we move into our panel discussion, we will learn more about where Maryland stands and what new and innovative approaches can strengthen our position. Thank you. ###