Principal Topic There is rapidly growing theoretical, empirical, and

advertisement

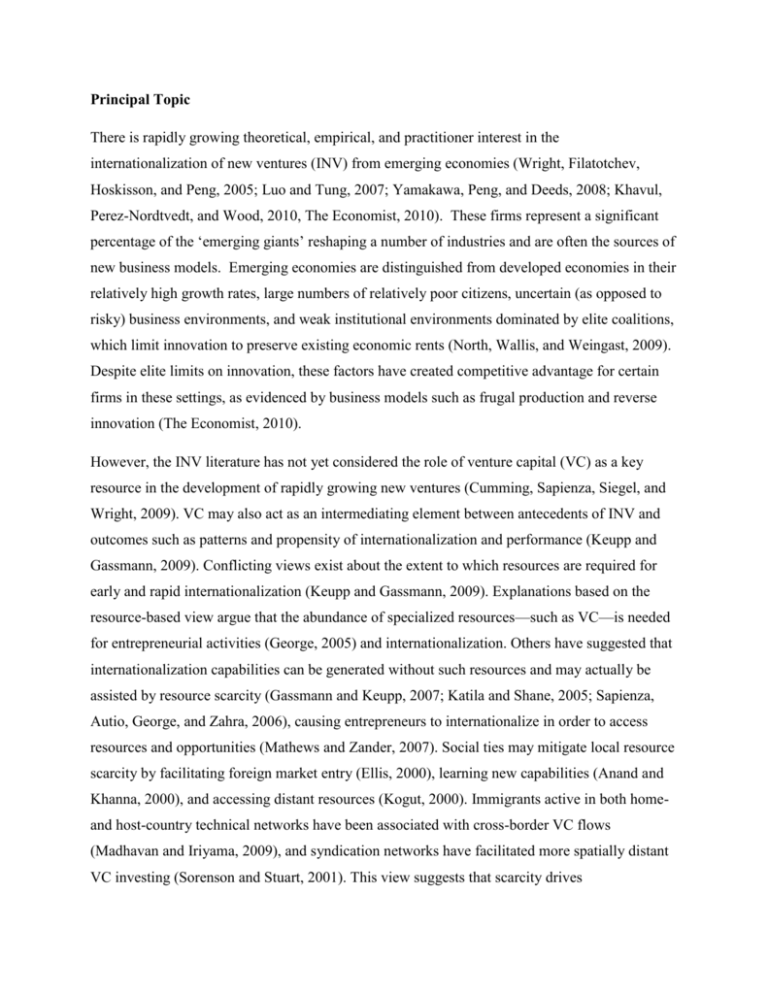

Principal Topic There is rapidly growing theoretical, empirical, and practitioner interest in the internationalization of new ventures (INV) from emerging economies (Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson, and Peng, 2005; Luo and Tung, 2007; Yamakawa, Peng, and Deeds, 2008; Khavul, Perez-Nordtvedt, and Wood, 2010, The Economist, 2010). These firms represent a significant percentage of the ‘emerging giants’ reshaping a number of industries and are often the sources of new business models. Emerging economies are distinguished from developed economies in their relatively high growth rates, large numbers of relatively poor citizens, uncertain (as opposed to risky) business environments, and weak institutional environments dominated by elite coalitions, which limit innovation to preserve existing economic rents (North, Wallis, and Weingast, 2009). Despite elite limits on innovation, these factors have created competitive advantage for certain firms in these settings, as evidenced by business models such as frugal production and reverse innovation (The Economist, 2010). However, the INV literature has not yet considered the role of venture capital (VC) as a key resource in the development of rapidly growing new ventures (Cumming, Sapienza, Siegel, and Wright, 2009). VC may also act as an intermediating element between antecedents of INV and outcomes such as patterns and propensity of internationalization and performance (Keupp and Gassmann, 2009). Conflicting views exist about the extent to which resources are required for early and rapid internationalization (Keupp and Gassmann, 2009). Explanations based on the resource-based view argue that the abundance of specialized resources—such as VC—is needed for entrepreneurial activities (George, 2005) and internationalization. Others have suggested that internationalization capabilities can be generated without such resources and may actually be assisted by resource scarcity (Gassmann and Keupp, 2007; Katila and Shane, 2005; Sapienza, Autio, George, and Zahra, 2006), causing entrepreneurs to internationalize in order to access resources and opportunities (Mathews and Zander, 2007). Social ties may mitigate local resource scarcity by facilitating foreign market entry (Ellis, 2000), learning new capabilities (Anand and Khanna, 2000), and accessing distant resources (Kogut, 2000). Immigrants active in both homeand host-country technical networks have been associated with cross-border VC flows (Madhavan and Iriyama, 2009), and syndication networks have facilitated more spatially distant VC investing (Sorenson and Stuart, 2001). This view suggests that scarcity drives internationalization and that poverty and uncertainty can be sources of competitive advantage, with important implications for INVs from emerging economies where resource scarcity is a fundamental attribute. As global economic conditions have shifted, innovation by local firms serving the ‘base of the pyramid’ (BoP) has become a source of competitive advantage (Hart and Christensen, 2002). The purpose of this paper is to explore the role of VC in the internationalization of new ventures from emerging economies in order to provide a more complete understanding of how weak institutional environments and poverty can create competitive advantage. Weak property rights protection has allowed ‘bandit’ or ‘guerilla’ innovation to emerge in a number of emerging markets. An emerging management paradigm based on findings from emerging markets has been articulated (Khanna and Palepu, 1997; Gulati, 2009; Immelt, Govindarajan and Trimble, 2009; Prahalad and Mashelkar, 2010). This paper aims to extend earlier process-based INV studies (Coviello, 2006; Mathews and Zander, 2007) by focusing on the central issue of resource scarcity and utilizing institutional theory. Institutional theory is the most appropriate lens through which strategic decisions in these settings can be studied (Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, and Wright, 2000), although it has not yet been widely applied to INV research (Cumming, Sapienza, Siegel, and Wright, 2009). Most INV research has focused to date on the US, UK, and Canada, lacks longitudinal data (Coviello and Jones, 2004), and does not consider that legal, institutional, and cultural factors may vary with time (Cumming et al., 2010), limiting the generalizability of these findings. Method Using longitudinal, quantitative and qualitative data from both primary and secondary sources, we develop three exploratory case studies of internationalizing new ventures from Russia, South Africa, and Peru. By comparing these three companies in three different countries, we can explore internationalizing new ventures along a diversity of characteristics, as shown in the table below: Table 1: Three companies in three countries – diversity along a variety of factors Industry Russia South Africa Peru Diversified business Medical devices Beverages group Legal origin French English French Firm size and age Large, established Small, established late Medium, established early 1990s 1990s late 1980s VC utilization Limited Extensive None Change in Extensive Moderate Limited institutional environment These cases are compared, from which a set of propositions are developed. Entrepreneurship is a process, rather than a static pattern, in which planned behavior changes over time in interaction with its external environment. Therefore, INV research is more likely to be robust if designed as a longitudinal study. The relative scarcity of quantitative data on entrepreneurial processes (Keupp and Gassmann, 2009) and the robustness of theory-building based on both qualitative and quantitative data (Edmondson and McManus, 2007) suggest that the use of comparative case analysis can be a source of research propositions in this immature field of study. Results and Implication We generate a set of propositions concerning the role of VC in INVs from emerging economies. These include: Proposition 1: If resource scarcity drives internationalization, then we can expect to see successful internationalization from emerging economies with lower levels of VC in comparison to INVs from economies with higher levels of VC. Proposition 2: In resource scarce emerging economies we can expect to find a higher reliance on social networks to facilitate internationalization. Proposition 3: The legal origin of home countries influences the effectiveness of INVs and their utilization of VC. Proposition 4: Changes in the institutional environments have an impact on VC’s role in the INV process in emerging economies.