Analysis of "Where Is Here?" by Joyce Carol Oates

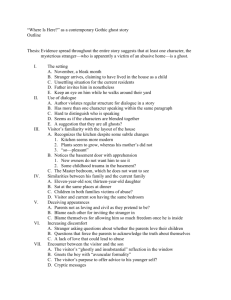

advertisement

1 Joyce Carol Oates’ “Where Is Here?” as a contemporary Gothic ghost story According to the editors of the Prentice-Hall Literature text entitled The American Experience, author Joyce Carol Oates’ discovery of the stories of Ann Radcliff and Edgar Allen Poe “sparked her interest in Gothic fiction” (324). These Gothic elements typically include “bleak or remote settings, macabre or violent incidents, characters in psychological and/or physical torment, supernatural or otherworldly elements, and strong language full of dangerous meanings” (291) . Oates herself is quoted as saying that “Horror is a fact of life. As a writer I’m fascinated by all facets of life” (324). What, exactly, does Oates mean when she says that horror is a fact of life? Do all people fear something, whether rational or not? Why does horror fascinate her enough to write about it? Is it a means for her to confront her own fears, coming to terms with them by giving them names and “faces” as other horror writers also do? Does she use this genre to indirectly address larger social concerns? Is she simply paying tribute to earlier Gothic writers by using elements from the genre or is this the most effective style for her to convey her ideas and duplicate Poe’s notion of the “single effect”? Finally, what is the point behind her short story entitled “Where Is Here?” Who is the mysterious stranger who arrives late in the evening? Why is he there? What lies behind his odd behavior and enigmatic questions and comments? What relationship, if any, does he have with the new family in his old home? How does his arrival and departure affect the family and why? And why does Oates use Gothic elements to create this narrative? Evidence spread throughout the entire story suggests that at least one character, the mysterious stranger--who is apparently a victim in an abusive home, is a ghost. But whose? A former inhabitant who has returned to his childhood “haunts”? The ghost of what the young boy currently living in the house will become? And if the latter, why is the grown ghost of the young boy there? Is he hoping to warn the child of some impending doom? However, Oates does not directly address any of these questions in the story, instead forcing the reader to test his own hypothesis, using many of the details (the “givens”) and the speculations noted below to arrive at the “mathematical proof.” In the story’s exposition, Oates introduces a family of four who have been living “without incident in their house in a quiet residential neighborhood” for an undisclosed number of years (325). Then one evening in November, arguably one of the bleaker months of the year, a stranger arrives, explaining he had lived in that house as a child. Adding to the feeling of uncertainty and discomfort for the reader and the family, the father invites the stranger into their home, by no means a typical response in that type of situation. Who openly invites a stranger into his home on a bleak, dark November evening? The stranger passes on the offer, saying instead, “I think I’ll just poke around outside for a while, if you don’t mind. That might be sufficient” (325). Still, the tone has been set for how this stranger will affect the family negatively. The wife speaks “uneasily” as she encourages her husband to “go out there with him” (325). And the husband moves “stealthily” (325) to each window, keeping an eye on the stranger, who has a “slight limp” and who could be “anyone, after all. Any kind of thief, or mentally disturbed person, or even a murderer. Ringing our doorbell like that with no warning….” (326). Interestingly, Oates defies the usual writing conventions with the dialogue in her story. Instead of beginning a new paragraph when a new of different character speaks, Oates has 2 more than one character speak in the same paragraph. Why? Is this merely her style or does she want the reader to see all of the characters as indistinct entities? And if so, for what purpose? Who truly is real in this story? Or are they all ghosts, a la M. Night Shyamalan’s film The Sixth Sense, souls who will ultimately learn the truth of their existence? Oates hints at the possibility of at least one ghost during a conversation between the stranger and the mother. Asking about the stranger’s own mother, she says, “Is your mother still living, Mr…?” To which their guest replies, “Oh, no, not at all…..We’ve all been dead--they’ve all been dead--a long time” (329). With one contraction--we’ve--the narrator hints at the truth: The visitor is a ghost, a fact that is further substantiated when Oates describes the stranger’s handshake as “cool and damp and tentative” (326). Cool and damp because he has been out in the cool November evening, or is it the cool, damp, and uncertain touch of a non-corporeal entity? There is little doubt that the visitor did spend part of his childhood in the house, as evidenced by even the most minute details he can recall when he enters each room. He first comments on the changes in the kitchen that is “‘so modernized’--he almost didn’t recognize it” (326). He notes the size of the windows being different, seeming to shrink, perhaps, as he grew? What seemed much larger to the eyes of a child has diminished for the adult stranger. However, in traditional Gothic fashion, Oates has the stranger’s pleasant nostalgic reveries at times give way to an undefined sense of dread and to hints of an unhappy past. He tells the mother that her kitchen is “so--pleasant” (327), more pleasant, it seems, than the kitchen his own mother kept, a kitchen that was “A--controlled sort of place” (327) where plants on the windowsill never seemed to bloom (or perhaps always died?). Oates seems to suggest that the boy may have been abused by his parents in this “controlled” house. Why else would he react as he does when he says, “That is the door leading down to the basement, isn’t it?” (327). The author notes that the visitor “spoke strangely, staring at the door” (327). Had he been locked in the basement as punishment? Had he met with a fatal accident in the basement or at least a fall that has caused him now to limp? Furthermore, why do the new owners not want to show him that part of the house? In a bizarre supernatural twist the new owners could be the ghosts of the visitor’s parents, and somehow he has returned to his childhood home as the adult spirit of his former self for a specific purpose. It can be no coincidence that he remembers living in the house, along with his parents and his sister, when he was eleven, and that the current family also includes two children: a girl, who is thirteen; and a boy, who is eleven. When the stranger notices the window seat, he says it was “one of [his] happy places! At least when Father wasn’t home” (328). Sometimes, he confides to the new owners, his mother would join him “If she was in the mood, and we’d plot together--oh, all sorts of fantastical things” (328). These lines suggest that both mother and son (and probably his sister as well) were the victims of the domineering father. And later, the visitor shows a great interest in seeing the son’s room upstairs--coincidentally his old room--but “the ‘master’ bedroom, in particular, he decidedly did not want to see” (329). Curiously, Oates uses quotation marks around the word master, perhaps suggesting not only an abusive father but also an abusive husband. Why else would the visitor consciously avoid that room? Similarly, is this also the case with the family currently living in the house? The parents seem to be very fond of each other and of their children. However, looks can be deceiving, as people mask their true selves. Throughout the story the reader sees cracks begin to appear in the thin veneer of civility the parents pretend to maintain, as the husband and wife blame each 3 other for inviting the stranger into their home and allowing him the freedom they have granted him as he explores each room. They even silently chide themselves (and blame each other?) for not asking him to leave before he begins to go upstairs: “So purposefully, indeed almost defiantly, did he limp his way to the stairs, neither the father nor the mother knew how to dissuade him. It was as if a force of nature, benign at the outset, now uncontrollable, had swept its way into the house!” (329). Clearly the parents’ discomfort continues to grow, quite possibly because of the liberties the visitor is taking and because they are too timid to intervene. And perhaps this visitor’s memories and comments force them to acknowledge some horrible truth about themselves. At one point the visitor asks why the couple had two children. “The father stared at him as if he hadn’t heard correctly. ‘Why?’ he asked. ‘Yes. Why?’ the stranger repeated… ‘But you love them--of course….Of course, of course,’ the stranger murmured, tugging at his necktie and loosening his collar, ‘otherwise it would all come to an end’” (330). Implied here is that a lack of love would result in a violent or fatal end, as may have happened to his sister and him, and perhaps his father as well. Oates states early in the story that the visitor’s mother was a widow when she moved from the house. Perhaps she killed her husband to escape his abuse. There is one more very uncomfortable encounter when the visitor talks with their son before the parents finally muster enough courage to kick the stranger out of the house. He first examines the boy’s room--his old room--commenting on how nothing has changed, with the exception, perhaps, of his substantial form. When he looks out the window, “his reflection bobbed in the glass, ghostly and insubstantial” (330). He then shakes the boy’s hand with an “avuncular formality” (330). The stranger is certainly not the boy’s uncle, as Oates suggests with the word avuncular. However, as the grown version of the boy or as a boy who had a similar childhood, he could offer the boy some “avuncular” advice, or a warning. However, his “advice” is very cryptic, only adding to the mystery surrounding him and his visit. Before meeting the son, the stranger spoke of how his mother used to share riddles and philosophical questions with him. The ones he remembers all deal with time, infinity, mortality, and man’s purpose and place in life: “What creature walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at midday, three legs in the evening?” (Man); What is round and flat, measuring mere inches in one direction, and infinity in the other?” (a watch); “Out of what does our life arise?” “Out of what does our consciousness arise?” “Why are we here?” “Where is here?” (328). The father confesses with “surprising passion” that he hates riddles (328-29), a passion that startles the mother. But is this just one small glimpse of the violent person that the father truly is? Nonetheless, these riddles may be significant to the stranger who has lived and died and will remain in his current limbo state forever. Unless he can return to his home and warn them about the consequences of their actions? Perhaps this is why he shows the son how to represent infinity with a square and a series of triangles on a sheet of paper. He claims the boy can “take it to school tomorrow and surprise [his] teacher!” (330). He offers no explanation beyond that for his drawing, but it seems to show his obsession with time as he “spoke with increased fervor; spittle gleamed in the corners of his mouth” (331). Clearly, he is hoping that at least the son sees some significance in his drawing of infinity. Why else would Oates include this scene along with the riddles about mortality and time? This uncomfortable scene serves as the coup de grace, finally shaking the parents from their passive nature, as they ask the stranger to leave. He consents, but oddly, as one last 4 favor he asks permission to sit on the basement stairs, in the dark, for just a few minutes. Perhaps the basement was not a means of punishment for him as a child but instead a refuge from his abusive father. Regardless, the parents deny his request and shut and lock the door behind the visitor. However, the couple and the house itself have undergone a change because of his appearance. The lights have begun to flicker, the wallpaper and carpet are now dingier, and the husband and wife are beginning to lose their tempers. Almost as if they are showing their true selves, the ghosts of their former selves who still inhabit this now-decaying house. The reader now sees more evidence of the anger and violence of the husband, who at one point when surprised by his wife’s touch “violently jerked his arm and thrust her away” (332). Oates then writes that “The mother entered the kitchen walking slowly as if she’d been struck a blow. In fact, a bruise the size of a pear would materialize on her forearm by morning” (332). Given the Gothic nature of the story, it is not too illogical to assume this is a bruise from an earlier time, a time when the mother was still being abuse by her husband before he died. Out of anger at the end of the story, she reminds her husband the he was the one who invited to stranger into their home. Arguably he was the one who forced both of them to finally acknowledge what truly did happen when they were all still alive in that house years ago, all of the anger, all of the abuse, and perhaps even death. And now because of the stranger’s visit, they are reminded of this hellish limbo they must endure for an eternity. Joyce Carol Oates certainly seems to offer enough evidence in this Gothic tale for the reader to arrive at this conclusion. She skillfully creates a bleak setting including actual and implied violent incidents and characters in psychological torment, not only the supernatural ghostly visitor but also the couple who are reminded of who they truly were and what they are now. Oates says that “Horror is a fact of life” only one of many facets of life. With horror, Oates seems to be addressing a larger social issue in this story, which can serve as an indictment of violent relationships and having to live with the consequences of your actions, just as these people have been relegated to their own hell for an eternity to reflect on their actions.