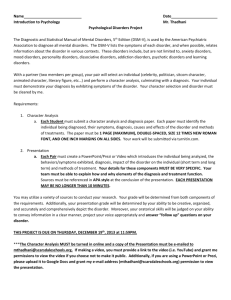

Booklet: Information

advertisement

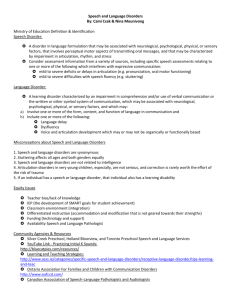

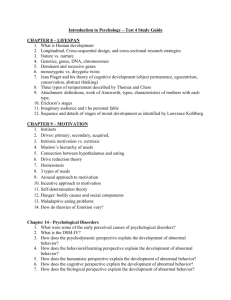

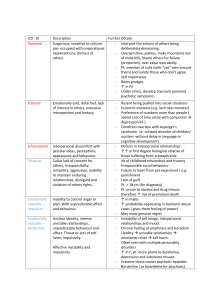

Diagnosis of Dysfunctional Behaviour The Theories/Studies 1. DSMI/ICD – Categories of Dysfunctional Behaviour 2. Rosenhan and Seligman (1995) – Definitions of dysfunctional Behaviour 3. Ford and Wediger (1989) – Sex Biases in Diagnosis of Disorders This section examines how dysfunctional behaviour is categorised and defined in order to help practitioners identify behaviours and consequently enable patients to get the help that is necessary. However, it highlights the reductionist nature of categorizing, and illustrates how taking holistic approach which takes into consideration individual differences and cultural diversity needs to be considered. The study then draws attention to how culture is affected when diagnosing by demonstrating that biases occur because of preconceived ideas about the nature of men and women, which ultimately affects the reliability of the methods used. 1.DSM / ICD - Categories of Dysfunctional Behaviour. Background: The definition of a mental disorder is important for investigation to enable a practitioner to identify and treat a particular disorder but it also helps for health care as well as for health care and the insurance industry (especially health insurance and pension insurance). The following elements are of particular importance for the definition of a mental disorder: Personal harm and suffering Abnormality (statistical, social, individual) Limitations or disabilities in what a person can perform Danger for others or the individual him/herself In most instances more than one of these elements has to occur at the same time and over a prolonged period of time. In order therefore, to standardize the description and interpretation of mental disorders, diagnosis and classification systems were set up. At present there are two established classification systems for mental disorders: The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the classification system of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Aim: To compare the two ways of categorising dysfunctional behaviour Approach/Perspective: Type of Data: Qualitative The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM-IV) This was compiled by over 1000 mental health professionals who collaborated to produce a practical guide to clinical diagnosis and help improve reliability of mental health diagnosis not just in US but around world This resulted in a simpler classification using criteria sets. The DSM is a diagnostic tool designed to enable practitioners to identify a particular disorder and therefore treat the disorder. It is updated regularly, with the current version being DSM-IV. It is complex with a range of Axis (variables to consider, alongside features of mental health there is social, physical and environmental issues also. This classification system of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), consists of five axes of disorders. The five axes of DSM-IV are: Axis I - Clinical Disorders (all mental disorders except Personality Disorders and Mental Retardation) Axis II - Personality Disorders and Mental Retardation Axis III – Etc.. The are 16 main categories of clinical disorders (Axis I) according to DSM-IV the ones we are concerned with are: 5.Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders 6.Mood Disorders 7.Anxiety Disorders Here there is some acknowledgement of individual differences as no individual is the same and thus, the features of their illness may not be the same. Also this manual attempts to highlight ethnic diversity and how a clinician from one culture may find it more difficult diagnosing someone from another culture. The classification of disorders can change with time; for example, until 1973 homosexuality was perceived as a mental disorder. As society became more enlightened it was removed from the DSM-II and replaced by the category ‘sexual orientation disturbance’. Again this changed to ‘ego-dystonic homosexuality’ in the DSM-III in 1980. In the DSM-III-Revised in 1987 a category of ‘sexual disorder not otherwise specified’ was introduced, and this has continued in the DSM-IV. The criteria here include ‘persistent and marked distress about one’s sexual orientation’. So it would appear now that society is not labelling homosexuality as a disorder, but that distress about one’s sexuality may lead to a disorder or to a diagnosis of a disorder. Newer disorders such as eating disorders are included as they become more identifiable in society. Bulimia was introduced as a disorder in DSM-III in 1980. Binge-eating disorder (BED) was introduced in 1994 into the 4th edition of DSM. The criteria for disorders such as anorexia can change over time; denial of having the disorder is now a criterion included in DSM-IV, and the body mass index (BMI) for anorexia was changed to allow for cross-cultural consistency. International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) This manual is published by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and is used in many countries throughout the world in diagnosing both physical and mental conditions. It was set up to track and diagnose diseases and mental health issues world-wide and consists of 10 main groups, the most notable for us are: F2 Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders F3 Mood [affective] disorders F6 Disorders of personality and behaviour in adult persons. In addition, there is a group of “unspecified mental disorders”. The ICD-10 was used in 40 countries to see if it improved psychiatric diagnosis across cultures, however, it is only a snap shot of dysfunctional behaviour and definitions and criteria must continue to be revised. Version 10 of the ICD was first published in 1992, and was a revision of previous versions. The ICD-8 was used as the basis for much cross-cultural collaboration in the 1980s, with the aim of refining the definitions for disorders in the 10th version. This allowed for inconsistencies and ambiguities to be removed and resulted in the clear set of criteria now found in ICD-10. The draft in 1987 was used in 40 countries to see if this improved psychiatric diagnoses across cultures. Of course ICD-10 is only a snapshot of the field of dysfunctional behaviour, and as cultures change so revision of definitions and criteria must continue to take place. ICD-11 should be drafted by 2008 Thus the major difference between ICD-10 and DSM-IV is that DSM a multi-axial tool. Clinicians have to consider if a disorder is from Axis 1 (clinical disorders) and/or Axis 2 (personality disorders). Then the general medical condition of the patient is considered, plus any social and environmental problems. This makes DSM more holistic in relation to diagnosing than the reductionist approach of the criteria based ICD. Many clinicians would use the two diagnostic tools side by side. 2. Rosenhan and Seligman (1995) Definitions of Dysfunctional Behaviour. Background: Culture refers to all ways of thinking, feeling and acting that people learn from other members of society. Different cultures will shown cross-cultural differences in beliefs, traditions, norms etc. and may have different views on defining and classifying abnormality. For example, in the West Indies it is perfectly acceptable to admit to hearing voices, it is considered a religious experience, people pray and God answers them. In Britain, hearing voices is considered a symptom of schizophrenia. Subculture: - This refers to a social group within a society e.g. gender, social class, age and ethnic groups. The dominant culture within a society is likely to be seen as the norm and subcultures as abnormal. The frequency of mental disorders can vary in relation to subcultures. For example, schizophrenia is between twice and eight times more prevalent in lower socio-economic groups in society. Rack (1984) found that African Caribbean’s in Britain are sometimes diagnosed as mentally ill, on the basis of behaviour which is perfectly normal within their subculture (hearing voices and smoking marijuana (cannabis psychosis)). Women are also more likely than men to be diagnosed with clinical depression. Some mental disorders have been found to be specific to certain cultures. The term given to these disorders is Culture Bound Syndromes (CBS), for example PMT and Anorexia Nervosa are particularly Western disorders. Abnormality is difficult to define. Views of abnormality change across cultures vary within cultures over time and vary from group to group (e.g. Chavs and Goths) within the same society (cultural relativism). It is essential to examine views of abnormality as they form the basis for defining and identifying psychological disorders. How do we decide what is ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’, and whether the behaviour constitutes a psychological disorder (e.g. depression, schizophrenia, phobias, post traumatic stress disorders, eating disorders etc.) Rosenhan and Seligman (1995) Frequency Aim: How can we define abnormality or normality? Approach/Perspective: Type of Data: Way 1: Statistical Infrequency A norm is a standard or rule that regulates behaviour in a social setting e.g. it is the norm in our society to be polite and say please and thank you. Norms are socially acceptable or ‘normal’ standards of behaviour. Abnormality is defined as moving away from the norm, non-compliance with society’s norms and values. In statistical terms human behaviour is abnormal if it falls outside the range that is typical for most people, in other words the average is ‘normal’. Things such as height, weight and intelligence fall within fairly broad areas. People outside these areas might be considered abnormally tall or short, fat or thin, clever or unintelligent etc. In statistical terms they Normal Distribution of IQ are abnormal because their behaviour has 120 moved away from the norm. 100 Example: - The Normal Distribution Curve 80 for IQ -This is calculated using 60 psychometric intelligence tests. The norm 40 for IQ is 100. Anything between 70 and 130 20 is considered normal for IQ, an IQ of less 0 0 50 100 150 200 than 70 or more than 130 is statistically IQ Score infrequent and therefore considered abnormal Mark on the graph the norm or average IQ score and the cut off points for abnormality (e.g. 100, 70 and 130). Limitations: The cut off points are rather arbitrary. How can someone with an IQ of 70 be considered normal, whilst a person with an IQ of 1 point difference (69) be considered abnormal? It ignores desirability of behaviour, in terms of IQ we might accept that someone has an abnormally low IQ, but we would probably all wish to have a high IQ and wouldn’t label that as abnormal. Some disorders, for example depression, are statistically very frequent, but still classified as abnormal. Way 2: Deviation from Social Norms Every society or culture has standards of acceptable behaviour/norms. Behaviour that deviates, (moves away) from these norms is considered abnormal. Social norms are approved and expected ways of behaving in a particular society or social situation. For example, in all societies there are social norms governing dress for different ages, gender and occasion Cultural and historical relativism: - what is statistically frequent and acceptable in one culture and time period is not necessarily the norm in another. For example, arranged marriages are statistically frequent in India, Marijuana smoking is statistically frequent in Jamaica. However, it is difficult to use on its own, as this might encompass behaviours such as exceptionally high IQ, or stamp collecting. So it is quite limited. Other behaviours might be quite common, such as depression diagnoses but it could be argued that this illness is dysfunctional. There has to be more to it than just numbers. Way 3: Failure to Function Adequately Perhaps a more useful definition is that if a person is not functioning in a way that enables them to live independently in society then they are “dysfunctional”. There are several ways a person might not be functioning well. These might be dysfunctional behaviours such as obsessions in obsessive compulsive disorder, where a person cannot leave the house due to the rituals they need to undertake before they can leave. If a person is distressed by their behaviour, not being able to go out of the house is distressing for agoraphobics. If the person observing the patient is uncomfortable this could be dysfunctional behaviour, such as when a person is talking to themselves whilst sitting next to you on the bus. Unpredictable behaviour, where a person might have dramatic mood swings or sudden impulses can also be seen as dysfunctional. Irrational behaviour, where a person might think they are being followed, or people are talking about them could also lead to a failure to function adequately. This failure to function adequately might be the most useful definition of the four. However, there are problems with this, in that the context of the behaviour might influence our view on it. We probably all talk to ourselves at times. Maybe a person who has been involved in a fire will obsessively check appliances before leaving the house. It can be quite a subjective view as to whether a person is not functioning adequately. Way 4: Deviation from Ideal Mental Health So far we have outlined definitions of abnormality. This definition instead attempts to define normality, and assumes that absence of normality indicates abnormality. However, normality is as difficult to define as abnormality. Jahoda (1958) approached this problem by identifying various factors that were necessary for ‘optimal living’ (maximising enjoyment for life). The presence of these factors indicates psychological health and well-being. Jahoda’s 6 elements of Optimal Living 1.Positive view of self: Well adjusted individuals have high self-esteem and self acceptance. 2.Personal Growth and Development: This refers to developing talents and abilities to the full. 3.Autonomy: The ability to act independently and make your own decisions. 4.Accurate view of reality: Seeing the world as it really is without distortions (lack of paranoia). 5.Positive Relationships: Normal people can form close, satisfying relationships with other people, both giving and receiving affection. They do not make excessive demands to satisfy their own needs. Mentally ill people may be selfcentred and look for affection, but are never able to find it. 6.Master of your own environment: Normal people can meet demands within different situations and are able to adapt to changing circumstances. 3. Ford and Widiger (1989) Biases in Diagnosis-Sex bias in the diagnosis of disorders Background: Boverman (1970)found that mental health professionals used different adjectives to describe normal male and female (submissive and concerned with appearance) which makes any female not fitting with this to be abnormal! This stereotypical view of genders is one way in which diagnosis can be biased. Aim: To find out if clinicians were stereotyping genders when diagnosing disorders Approach/Perspective (if any): Individual differences Type of Data: Quantitative Method: Self-Report where health practitioners were given scenarios and asked to make diagnoses based on the information. The independent variable was the gender of the patient in the case study and the dependent variable the diagnosis made by the clinician Details: 354 clinical psychologists from 1127 randomly selected from the National Register, with a mean 15.6 years clinical experience. 266 psychologists responded to the case histories. An independent design as each participant was given either a male, female or sexunspecified case study. Participants were randomly provided with one of nine case histories. Case studies of patients with anti-social personality disorder (ASPD) or histrionic personality disorder (HPD) or an equal balance of symptoms from both disorders were given to each therapist. Each case study was male, female or sexunspecified. Therapists were asked to diagnose the illness in each case study by rating on a 7-point scale the extent to which the patient appeared to have each of nine disorders 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Dystheymic (form of mild depression) Adjustment (stress-related disorder due to social/emotional issues) Alcohol abuse Cycothymic disorder (type of depression resulting in frequent mood disorders) Narcissistic (a personality disorder in which people have inflated sense of self and little regard for other’s feeling’s. Underpins lack of self-esteem) Histrionic (personality disorder whereby suffer shows excessive emotionality and attention seeking. Can include inappropriate seductive bahvaiour) Passive-aggressive (personality trait manifested negatively, eg. learned helplessness) Antisocial (behavioural pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others that begins in childhood or early adolescence and continues into adulthood) Borderline personality disorder (a condition in which a person makes impulsive actions, and has an unstable mood and chaotic relationships) Results; Sex-unspecified case histories were diagnosed most often with borderline personality disorder. ASPD was correctly diagnosed 42% of the time in males and 15% of the time in females. Females with ASPD were misdiagnosed with HPD 46% of the time, whereas males were only misdiagnosed with HPD 15% of the time. HPD was correctly diagnosed in 76% of females and 44% of males. Conclusions: Practitioners are biased by stereotypical views of genders as there was a clear tendency to diagnose females with HPD (histrionic personality disorder) even when their case histories were of ASPD (antisocial personality disorder). There was also a tendency not to diagnose males with HPD, although this was not as great as the misdiagnosis of women Summary: Diagnosis of Dysfunctional Behaviour It is clear that diagnosing and categorising dysfunctional behaviour is not an exact science. Diagnosing often depends on how society views any particular disorder at any one time, and the biases inherent in that society. There are dysfunctional behaviours that cause distress to patients and their families, and which can be treated to facilitate a better quality of life.