full paper

advertisement

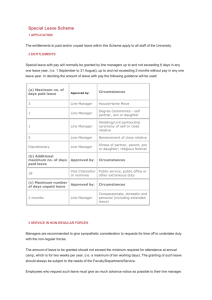

Wage share and corporate policies in personnel management: A firm-level study Byung-Hee Lee1 and Deok Soon Hwang2 1. Introduction The share of labor in national income has been declining in most developed countries since the 1980s. Many explanations has been suggested to account for the decline in the labor share. They include technological progress, globalization, institutional and policy changes and so on. This paper will address the role of corporate policies in personnel management. Korea has been experiencing big changes in labor market towards flexibilization since the 1997 Asian financial crisis. At the same time the labor share, adjusted for self-employment income, declined by about 10 percentages points in Korea. Increase in non-regular workers and outsourcing are some of the leading examples of HR policies that businesses adopted as a way to pursue higher short-term profitability. This study analyzes the impact of such changes in corporate HR policies on labor income share. In this context, this paper investigates a functional income distribution at the firm level. It is within individual firms that divide between labor and capital of economic gains is ultimately decided. A firm-level analysis is also relatively free from the problem of composition bias that arises by the shift in employment from labor intensive sectors to capital intensive sectors. Moreover it also does not require separation of labor income and capital income from the mixed income of the self-employed (Siegenthaler and Stucki, 2014). The data used in this study is panel data. The panel nature of data enables us to resolve the issue of endogeneity. 1 2 Senior Research Fellow, Korea Labor Institute, e-mail address: lbh@kli.re.kr Senior Research Fellow, Korea Labor Institute, e-mail address: deoksoonh@gmail.com -1- I explores the determinants on the wage share on the firm level. The role of technical progress (measured by capital-labor ratio and R&D), imperfect market competition, union density will be examined. Especial concern in the paper is the corporate policies in personnel management. I focus the effect of both the ratio of nonregular work and subcontracting. 2. Literature Review The causes of changes in the labor income are often identified as changes in the industrial structure, technological change, globalization, the degree of monopoly in the product market, labor and management's bargaining power, and the increase in the financialization. Empirical study results vary as to the impact of each factor, which lead to divergent policy implications. The Neoclassical economics tend to look to capital-augmenting technical change and globalization as the main causes of the decline in labor income share in recent decades. Bentolila and Saint-Paul (2003) concludes that the decline in labor share is attributed to capital accumulation and capital-augmenting technical progress. Arpaia et al. (2009) points to technological factors, such as capital-augmenting technological development and complementarity between capital and skilled labor. OECD (2012) also concludes that 80% of the fall in the within-industries labor share of OECD members between 1990-2007 is attributable to technological development and increase in capital intensity. The European Commission (2007) demonstrated that skill-biased technological development is the main cause of labor income share decline, followed by globalization. If the fall in labor income share is mainly due to such structural changes, it leaves little room for policy intervention. What policymakers can do is to run macroeconomic policies in a way that promotes capital accumulation and technological advancement and emphasizes training and education for low-skilled workers who are most negatively affected by the drop in labor income share (caused by structural changes) (Sang-Heon Lee, 2014). In contrast, Michal Kalacki and post-Keynesian economists place more weight on policies and institutions. Stockhammer (2013) and ILO (2012) highlight the role of institutional changes such -2- as financialization of the economy and weakening of the labor market institutions and welfare state. In developed countries, the impact is larger in the order of financial globalization, institutional changes, globalization and technological changes. In developing countries, it is in the order of financialization, globalization and institutional changes while technological changes actually offset the decline in labor income share because of the catch-up effect. Dunhaupt (2013) demonstrates that financialization of the economy is the main cause of the fall in labor income share in OECD members. The spread of shareholder value-maximizing management ends up putting pressure on wage, by focusing on short-term profits and lower labor cost and increasing financial income such as dividends and interest. Almost all studies used cross-country or industrial data, rarely firm-level data. Siegenthaler and Stucki (2014) uses panel data on Swiss companies' innovation activities collected across four waves between 2001-2010 and find that the main factor deceasing labor share is the increase in the share of workers using ICT in the firm. Growiec (2012) uses the quarterly panel data of the private sector in Poland between 1995-2008 to identify the determinants of labor income share. He takes into account such factors as ownership structure, labor market conditions, market structure and age of the company. This study firm-level panel data to analyze the impact of each of the following factors on labor market share: technological factors (capital intensity, innovation), level of competition in the product market, union density, use of non-regular workers, and outsourcing. 3. Data for analysis The data used in this study combines data from Workplace Panel Survey (WPS) conducted by the Korea Labor Institute with accounting data. Every two years from 2005 to 2011, the WPS surveyed about 2,000 workplaces with 30 or more full-time workers in all industries with the exception of the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector and the mining sector. All data from the first to the fourth waves are currently available from this survey for which the fourth wave panel retention -3- rate was 62.5% and where lost samples were replaced with workplaces of a similar size that is in a similar industry sector. The analysis in this study only utilizes data on private sector workplaces. This study analyzes corporations in the private sector. For the figures of capital, this study uses accounting data on the year-end balance of tangible assets, which represent the sum of the value of land, buildings, machinery and vehicles. For the figures of intermediate input, accounting data on the cost of sales in used. All variables representing production input and final output are deflated with the Production Price Index. Whereas the WPS conducts survey at the establishment level, financial information used in this study comes from the level of firms. This discrepancy is reconciles through the standardization of data. For firms with multiple establishments, the proportion of workers in a certain establishment out of the total workers in the firm is multiplied with the variables to convert the financial information to establishment-level. Meanwhile, the per capital variables (including per capita value-added) are all results of dividing each variable with the total number of employees. Employment types in the WPS are classified as follows. Total employees is defined as the sum of regular and non-regular workers. Non-regular workers are either directly or indirectly employed. Directly-employed non-regular workers include fixed-term contract workers and part-timers. Indirectly-employed workers include temporary agency workers who are dispatched to workplaces under the Act on the Protection of Temporary Agency Workers, in-house subcontract and contract company workers who are hired by subcontractors but who provide labor in the workplace of the principal contractor who are not entitled to the Act on the Protection of Temporary Agency Workers, and independent contractors who provide commissioned labor as self-employed individuals. The firm-level measure of the labor share does not face with the problem of having to separate labor income from self-employed's mixed income. The labor income share is calculated as the percentage of labor cost out of the value-added at factor cost (i.e. sum of operating surplus, financial costs and labor cost). Samples with operating loss are excluded as they show overblown labor income share. In the end, an unbalanced panel of 4 years is created consisting of 1,579 -4- establishments of only corporations in the private sector. The trend in labor income share in this study is compared with that of Financial Statement Analysis (FSA) conducted by Bank of Korea (see [Figure 1]). FSA does not allow for understanding of the time-series trends of the labor income share because of frequent changes in corporate accounting standards and survey scope. It expanded the population for sample design in 2007 to include all corporations subject to corporate income tax, including small businesses. Figure 1 shows an identical level of labor income share between the two surveys in 2007, then lower level for the WPS in 2009 and 2011. However the trends are similar. It dropped in 2009 as corporate financial situation deteriorated following the global financial crisis then rebounded in 2011, but remains lower than the pre-crisis level. Figure 1. Trends in the labor share on the firm level (Unit: %) 72 70 68 66 WPS 64 FSA (2007-10) FSA (2009-12) 62 60 58 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Note: There is a time-series interruption in 2009 in the statistics of FSA due to change in the survey method. Source: Workplace Panel Survey and Financial Statement Analysis. 4. Empirical Methodology The determinants of the labor share will be analyzed using the estimation equation in Bentolila -5- and Saint-Paul (2003). They assumes a production function where the elasticity of substitution remains constant. 𝑄𝑖 = [𝛼(𝐴𝑖 𝐾𝑖 )𝜀 + (1 − 𝛼)(𝐵𝑖 𝐿𝑖 )𝜖 ]1−𝜀 In this equation, 𝑄𝑖 is the output of firm i, and 𝐾𝑖 and 𝐿𝑖 are input of capital and labor respectively. 𝐴𝑖 is capital-augmenting technical change and 𝐵𝑖 is labor-augmenting technical change. ε is the parameter whose relationship with the elasticity of substitution σ is represented as σ ≡ 1/(1 − ε). α is the distribution parameter. In a perfectly competitive market, labor demand will be determined at the point where the price of labor is equivalent to the value of the marginal product of labor. In this context, the labor income share can be calculated as follows. (1−α)(𝐵 𝐿 )𝜖 𝑖 𝑖 𝐿𝑆𝑖 = 𝛼(𝐴 𝐾 )𝜀 +(1−𝛼)(𝐵 𝐿 )𝜖 𝑖 𝑖 𝑖 𝑖 In this equation, the closer ε is to 0, the production function converges to the Cobb-Douglas production function, while the labor income share converges to 1 − α. They use capital/output ratio in the equation, but this study uses capital/labor ratio in accordance with the EU Commission (2007). When capital intensity is 𝑘𝑖 = 𝐾𝑖 /𝐿𝑖 and technical parameter ratio is 𝑇𝑖 = 𝐴𝑖 /𝐵𝑖 , the labor share is equal to: (1−α) 𝐿𝑆𝑖 = 𝛼(𝑘 𝑇𝐾 )𝜀+(1−𝛼) ≡ g(𝑘𝑖 , 𝑇𝑖 ). 𝑖 𝑖 The equation above shows that the labor share is determined by capital intensity, technical parameter ratio and elasticity of substitution between labor and capital. How much capital intensity and technical parameter ratio respectively affect labor share depends on the elasticity of substitution. When labor and capital are substitutive ( ε < 0 or σ > 1 ), increase in capital intensity reduces labor income share. But if they are complementary ( ε > 0 or σ < 1 ), it increases the labor income share. If it is the Cobb-Douglas production function (ε = 0 or σ = 1), labor income share remains unchanged despite increase in capital intensity. Meanwhile, the technical parameter ratio 𝑇𝑖 changes depending on the nature of technical change. If labor and -6- capital are substitutive, capital-augmenting technical change increase 𝑇𝑖 and reduces labor income share. But labor-augmenting technical change has the opposite effect: it reduces 𝑇𝑖 and increases labor income share. The above assumes that the labor income share is determined by capital intensity and technological factors such as technical parameter ratio. But if the product market and labor market are not perfectly competitive, the institutions that affect competition in the product market and relative bargaining power in the labor market also affect the labor income share. When firms are in imperfect competition in the product market, price is determined at a higher level than the marginal production cost. If the ratio between product price (𝑝𝑖 ) and marginal cost (𝑀𝐶𝑖 ) is the mark-up rate (𝜇𝑖 = 𝑝𝑖 /𝑀𝐶𝑖 ), when firms seek maximum profit in an imperfectly competitive market, the labor income share is determined as follows: 𝐿𝑆𝑖 = g(𝑘𝑖 , 𝑇𝑖 )/𝜇𝑖 . That is, the mark-up rate and labor income share have a negative correlation. And the impact of bargaining power of labor to management on labor income share depends on the bargaining model. In a right-to-manage model where labor and management negotiate only the wage, and where the management has the full authority to make employment decisions, the impact would depend on the elasticity of substitution between production factors. That is, when workers' bargaining power increases and succeeds in improving wage, hiring would decrease. But the labor income share could either rise or fall depending on the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor. But in an efficient bargaining model where labor and management negotiate for both wage and employment, workers' bargaining power is bigger and thus hiring does not decrease with higher wage. If workers' relative bargaining power is 𝜃𝑖 , the labor income share is determined as: 𝐿𝑆𝑖 = 𝜃𝑖 + (1 − 𝜃𝑖 )g(𝑘𝑖 , 𝑇𝑖 ). This means that increase in workers' bargaining power brings up the labor income share regardless of elasticity of substitution. The estimation model in this paper is as follows: 𝑗 ln𝐿𝑆𝑖𝑡 = 𝛽𝑜 + 𝛽1 𝑙𝑛𝑘𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽2 𝑇𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽3 𝜇𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽4 𝜃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽5 𝜃𝑖𝑡 + ∑𝑗 𝛽𝑗 𝑋𝑖𝑡 + 𝜂𝑖 + 𝜆𝑡 + 𝜖𝑖𝑡 As for the factors that affect labor income share, capital intensity, technological factors, and the -7- extent of competition in the product and labor markets, have been included in accordance with the previous studies. As for the capital intensity, it was represented using the year-end value of real per capita tangible assets in the accounting data. WPS lacks quantitative information on R&D. As for technological factors, this study uses qualitative information on innovation types. Each innovation type is given the following dummies: "process improvement with only production engineering without R&D," "R&D implemented only when necessary, to the extent of introducing new technologies developed by other companies," and "leading innovation with R&D." As for the extent of competition in the product market, dummy variables are generated by using 1 for very weak or weak competition for the main product and 0 for others. The extent of competition in the labor market is measured using the union density rate. To measure the impact of corporate policies in personnel management on the labor income share, the main topic of interest of this study, the corresponding variable (𝑆𝑖𝑡 ) was added to explanatory variables in the equation. The proportion of non-regular workers is calculated by the number of non-regular workers by the number of all workers. As for outsourcing, the value of 1 is given to the principal company in subcontracting transactions for the firm's main product (that only contracts out) and 0 for others. In the estimation model above, 𝜂𝑖 represents the unobservable heterogeneity of the firm. If such unobserved factor exists, it could lead to the problem of endogeneity where correlation exists between the variable of this study's interest and the error term, resulting in overestimation of the effect of the variable of interest. Unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity is normally estimated using panel regression analysis. But fixed-effect model is not only limited to surviving firms but uses information on within-firm variations only (Siegenthaler and Stucki, 2014). Thus it is not able to account for the inter-firm differences in such structural and strategic factors as production techniques, market circumstances and use of labor. This study attempted to control for the inter-firm heterogeneity by including the labor income share of the previous term in the pooled OLS estimation. Including previous term's labor income share not only controls for part of the endogeneity due to missing variables but also the -8- endogeneity caused by reverse causation. If a firm's behavior is affected by past labor income share, previous term's dependent variables can control for the changes in corporate strategy according to the labor income share. But this does not fully address the problem of endogeneity. Labor income share, investment and choice in technical factors such as R&D can still be associated with firms' unobserved heterogeneity. Unobserved demand shock or productivity change can affect labor income share and explanatory variables, creating false correlation. Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) focuses on firms' practice of first adjusting the intermediate input when faced with an unobserved exogenous shock. Intermediate goods are not included in calculation of the value-added, and thus have no direct impact on the share of labor or capital. The ratio of intermediate input controls for the variable heterogeneity and helps reduce the simultaneity bias. In this study, the share of manufacturing cost out of value-added is included in the estimation model. In accordance to the analysis by Growiec (2012) concluding that the characteristics of the business establishment also affect the labor income share, the log value of total employees, age of the establishment and industry (manufacturing or not) are included. Year dummy has also been added to control for the effect of economic cycles. Basic statistics as of 2011 for these variables are presented in <Table 1>. As of 2011, business establishments that use non-regular workers account for 68.5% of the total, and their labor income share, at 64.7%, is lower than that of the establishments that do not have non-regular employees (69.5%). Those that use non-regular labor are found to be relatively high in capital intensity, R&D intensity, number of employees, union organization rate, share of principal companies and company age, with less competition in the market. Meanwhile, 14.7% of total business establishments were found to be principal companies that only contract out in subcontracting transactions. By type of subcontracting, principal companies have much lower labor income share than subcontractors or those who do not engage in subcontracting transactions. -9- Table 1. Sample Characteristics of 2011 Non-regular workers In use Mean Outsorucing Not in use (SD) Mean (SD) Principal Mean (SD) Others Mean (SD) Labor income share 0.647 (0.232) 0.695 (0.220) 0.597 (0.247) 0.673 (0.224) Log (per capita capital) 4.074 (2.034) 3.761 (2.247) 4.715 (1.874) 3.847 (2.120) No R&D 0.077 (2.034) 0.116 (0.321) 0.029 (0.169) 0.100 (0.300) Process improvement with no R&D 0.200 (0.267) 0.164 (0.371) 0.117 (0.322) 0.201 (0.401) R&D only when needed 0.230 (0.400) 0.215 (0.412) 0.248 (0.434) 0.221 (0.415) Leading innovation with R&D 0.494 (0.421) 0.505 (0.501) 0.606 (0.490) 0.479 (0.500) Weak competition in market 0.046 (0.209) 0.041 (0.199) 0.051 (0.221) 0.043 (0.203) Union density rate 0.222 (0.316) 0.151 (0.292) 0.278 (0.331) 0.186 (0.304) Non-regular workers (%) 0.226 (0.237) Principal (contracting out) 0.170 (0.376) 0.099 (0.299) Log (# of employees) 5.575 (1.214) 4.757 (1.195) 5.809 (1.276) 5.232 (1.245) Company age 25.49 (16.00) 22.32 (13.19) 28.78 (16.15) 23.75 (14.96) Manufacturing 0.616 (0.487) 0.683 (0.466) 0.708 (0.456) 0.625 (0.484) Sample size % of applicable companies 0 0.196 (0.227) 0.148 (0.221) 1 0 636 293 137 792 0.685 0.315 0.147 0.853 5. Estimation Result <Table 2> shows estimation results of determinants on labor income share. Column (1) includes intermediate input to control for firms' time-variant heterogeneity, while Column (2) additionally includes previous term's labor income share. Column (1) shows, firstly, capital intensity has a significant negative effect on labor share. According to the discussion above, this result implies that labor has substitutive relationship with capital. Secondly, when labor and capital are mutually substitutive, the impact on labor income share depends on the nature of technical change. Although it was not presented separately, the "innovation-leading" companies stating that innovation is the key to their competition strategy - 10 - have a significant positive correlation with capital intensity. Innovation-leading type is likely to cause capital-augmenting technical change. The hypothesis that capital-augmenting technical change will pull down the labor income share if labor and capital are substitutive is supported in the result. Innovation-leading type has a significantly lower labor income share than other types. Thirdly, firms with less market competition have significantly lower labor income share than others. In a product market with imperfect competition, firms are likely to set the price at higher than the production cost. Fourthly, it was also found that the higher the union density rate, the higher the labor income share. This is so despite the substitutive relationship between labor and capital because employment does not go down as wage rises, or goes down only by a minimal extent. Meanwhile, in terms of the impact from corporate HR policies, the topic of interest of this study, it was found that the higher the proportion of non-regular workers, the lower the labor share. The definition of "non-regular workers" in this study also includes indirectly-employed workers, but their cash and value-in-kind compensation is not included in the firms' payroll. Although nonregular workers' productivity and wage cannot be compared, it can be interpreted that the use of non-regular labor reduces the labor income share not because it ends up distributing more of the value-added to regular workers but because it helps increase the share of capital income. In terms of principal companies' labor income share, it is significantly lower than subcontractors or those that do not engage in subcontracting. If subcontracting has unfair conditions, more of the benefits will belong to principal companies, but the fact that labor income share is lower even when other factors are controlled for indicates that more of them are accrued to capital income rather than the rent distribution within the principal company. As for impact of other control variables, it was found that the larger the company size, the lower the labor income share. Although it was not possible to discern any difference between new businesses and continuing establishments due to limitations of panel data, the age of company does not appear to have a significant impact. In terms of the year effect, labor income share was much lower in 2009 compared to 2005, and was also significantly lower in 2011. Estimation Result of column (2) where the previous term's log labor income share has been - 11 - added to control for endogeneity shows that although the significant of the estimation coefficients fell, the sign is largely similar. The estimation result where the impact of previous term's labor income share was found to be large implies that the unobserved firm characteristics are large. Table 2. Estimation of determinant of labor share in the firm level (Pooled OLS) (1) (2) Log(capital intensity) -0.089 (0.004) Process improvement without R&D -0.042 (0.035) -0.036 (0.038) R&D only when needed -0.039 (0.034) -0.026 (0.036) Leading innovation with R&D -0.084 (0.033) ** -0.062 (0.035) * Market competition is weak -0.149 (0.034) *** -0.054 (0.036) 0.136 (0.028) *** -0.009 (0.028) Non-regular workers % -0.173 (0.039) *** -0.095 (0.040) ** Principal (contracting out) -0.041 (0.020) ** -0.025 (0.021) Share of manufacturing cost 0.001 (0.003) 0.008 (0.003) ** Share of manufacturing cost, squared 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) -0.024 (0.007) Age of workplace 0.000 (0.001) Manufacturing 0.018 (0.017) 2007 0.007 (0.022) 2009 -0.079 (0.022) *** -0.107 (0.020) *** 2011 -0.051 (0.022) ** -0.004 (0.020) 0.083 (0.048) * Union density rate Log (# of employees) Constant Lag of dependent variable *** *** -0.029 (0.005) *** -0.009 (0.007) 0.000 (0.001) -0.049 (0.018) *** 0.093 (0.050) * 0.693 (0.017) *** Adj R-squared 0.135 0.517 N 3,621 2,110 Notes: 1) The reference group has the following characteristics: weak market competition, not a principal company (i.e., subcontractor or no subcontracting), service sector, 2005. 2) Standard errors are in parentheses. 3) * significant at 10% level; ** significant at 5% level; *** significant at 1% level. - 12 - To control for the unobserved firm characteristics, a number of different models have been additionally estimated. The results are presented in <Table 3> for comparison. Results of the random effect model that uses both inter-firm and intra-firm information are similar to those of the pooled OLS, but quite different from those of the fixed-effect model where only intra-firm information is used. In the fixed-effect model, impact of the variables of interest is not significant, except for that of R&D/innovation. But the fixed-effect model is preferred because the Hausman test cannot reject the null hypothesis that the covariance between unobserved firm characteristics and explanatory variables is 0. This also shows the importance of controlling for endogeneity. But if it is important to account for the structural and strategic differences between firms, pooled OLS or random effect model results would be better suitable in identifying the determinants of labor income share. In terms of the effect of corporate policies in personnel management, pooled OLS or random effect model shows that 10%p increase in non-regular workers reduces labor income share by 0.9%. And a principal company's labor income share is 0.03%p lower than that of subcontractors or those that do not engage in contracting. Table 3. Estimation of determinant of labor share in the firm level (Pooled OLS, REM & FEM model) (2) (3) (4) Pooled OLS REM FEM Log(capital intensity) -0.029 (0.005) *** -0.065 (0.005) *** 0.008 (0.008) Process improvement without R&D -0.036 (0.038) -0.062 (0.029) ** -0.061 (0.032) * R&D only when needed -0.026 (0.036) -0.047 (0.028) * -0.045 (0.031) Leading innovation with R&D -0.062 (0.035) * -0.083 (0.027) *** -0.069 (0.030) ** Market competition is weak -0.054 (0.036) -0.086 (0.030) *** -0.026 (0.032) Union density rate -0.009 (0.028) Non-regular worker % -0.095 (0.040) ** -0.089 (0.034) *** 0.046 (0.041) Principal (contracting out) -0.025 (0.021) -0.032 (0.016) ** -0.017 (0.017) Share of manufacturing cost 0.008 (0.003) ** - 13 - 0.040 (0.032) 0.023 (0.004) *** -0.047 (0.061) 0.074 (0.006) *** Share of manufacturing cost, squared Log (# of employees) Age of firms 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) *** -0.001 (0.000) *** 0.008 (0.015) -0.004 (0.015) -0.009 (0.007) 0.000 (0.001) Manufacturing -0.049 (0.018) *** 2007 2009 -0.107 (0.020) *** -0.096 (0.015) *** -0.129 (0.016) *** 2011 -0.004 (0.020) -0.070 (0.016) *** -0.108 (0.016) *** -0.169 (0.034) *** -0.637 (0.049) *** Constant 0.093 (0.050) * Lag of dependent variable 0.693 (0.017) *** Adj R-squared 0.517 Wald chi2 296.66 *** F value N 21.52 *** 2,110 3,621 3,621 Notes: 1) The reference group has the following characteristics: weak market competition, not a principal company (i.e., subcontractor or no subcontracting), service sector, 2005. 2) Standard errors are in parentheses. 3) * significant at 10% level; ** significant at 5% level; *** significant at 1% level. 6. Summary and Policy Implications This paper analyzed the determinants of labor income share at the firm level. Main results are summarized as follows. Labor income share in a firm is determined not only by technical factor but also other factors such as the degree of monopoly in the product market, employees' bargaining power and corporate labor strategy. Capital intensity and R&D have a negative effect on labor income share. In comparison, the weaker the competition in the product market, the lower the labor income share, and the higher the union density rate, the higher the labor income share. And the higher the non-regular employee share, the lower the labor income share. Principal companies that only contract out are found to have a lower labor income share. Based on such analysis, this paper focuses on the following implications. First, the analysis result that higher share of non-regular employees leads to lower labor income - 14 - share implies that even if pecuniary gain is created from utilizing non-regular labor, it is accrued to capital income, not to under regular workers. It also means that there should be policy efforts to ensure fair distribution of the fruits of production between labor and capital, going beyond simply trying to ease inequality in the labor income. Second, , the analysis result that labor share for principal company in subcontracting transactions is higher than others even when various factors are controlled for shows that the benefits of subcontracting transactions are attributed to the principal company's capital income. This implies that efforts to improve unfair subcontracting transactions must be undertaken to ensure fair distribution. References Arpaia, A., E. Pérez and K. Pichelmann (2009), "Understanding Labour Income Share Dynamics in Europe", Economic Papers 379, Directorate General Economic and Monetary Affairs, European Commission. Bentolila, S. and G. Saint-Paul (2003), "Explaining movements in the labor share", Contributions to Macroeconomics, 3(1), 1–3. Dunhaupt, P. (2013), “The effect of financialization on labor’s share of income”, Working Paper No. 17/2013, Berlin: Institute for International Political Economy, Berlin School of Economics and Law. European Commission (2007), "The labour income share in the European Union", Employment in Europe, 237– 272. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Growiec, J. (2012), "Determinants of the Labor Share: Evidence from a Panel of Firms", Eastern European Economics, 50(5), 23-65. ILO (2012), Global Wage Report 2012/13: Wages and Equitable Growth, Geneva: ILO. Levinsohn, J. and A. Petrin (2003), "Estimating Production Functions Using Inputs to Control for Unobservables," Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317-341. OECD (2012), "Labour Losing to Capital: What Explains the Declining Labour Share?", Employment Outlook, Paris: OECD. - 15 - Siegenthaler, M. and T. Stucki (2014). "Dividing the Pie: the Determinants of Labor’s Share of Income on the Firm Level", KOF Working Paper No. 352. Stockhammer, E. (2013), "Why Have Wage Shares Fallen? An analysis of the Determinants of Functional Income Distribution", Mark Lavoie and Engelbert Stockhammer, Wage-led Growth: An Equitable Strategy for Economic Recovery, Palgrave macmillan and the ILO. - 16 -