Wind Power Legitimacy in the Netherlands

advertisement

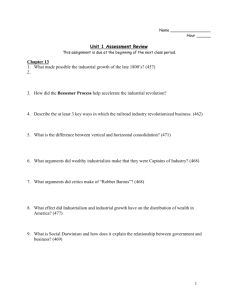

Utrecht University Wind Power Legitimacy in the Netherlands Bachelor Thesis Sosef, M.N. (3508943) Word count: 3594 1/24/2014 Supervisor: prof. dr. M. Hekkert Summary For an innovation to be successful it does not only rely on its physical attributes. It also needs integration in the environment in which it is developed. This environment is also called the Technological Innovation System which consists of several functions. One of these is Legitimacy. A high legitimacy aids the integration in the environment and is influenced through the actions of organizations and individuals that frame the technology in a particular way to influence how others see the technology. In this research legitimacy in the Dutch wind power discourse has been examined through analysis of newspaper articles. The resulting database is used to answer how legitimacy changed and which actors where involved in this. It is found that legitimacy for wind power decreased from slightly more positive to slightly more negative and that this is accompanied by a change in dominant frames which is likely the result of a group of actors with the strongest support for these frames. Samenvatting Een innovatie heeft meer nodig dan zijn fysieke eigenschappen om succesvol te worden. Het moet ook voldoende integratie in de omgeving vinden waarin het ontwikkeld word. Deze omgevind wordt ook wel het Technologische Innovatie Systeem genoemd bestaande uit verschillende functies. Een van deze functies is Legitimiteit. Een hogere legitimiteit helpt bij de integratie in de omgeving en wordt beinvloed door de acties van organisaties en individuen die de innovatie op en bepaalde manier omschrijven. Hiermee proberen ze andere actoren te overtuigen van hun standpunten door het gebruik van frames. In dit onderzoek is de legitimiteit voor wind energie in de nederlandse redevoering onderzocht door het analyseren van kranten artikelen. De database die hieruit voortvloeide is gebruikt om the kijken hoe de legitimiteit is veranderd en welke actoren daarbij betrokken waren. Het is gebleken dat de legitimiteit voor wind energie in nederland gedaald is van lichtelijk positief naar lichtelijk negatief en dat dit vergezeld is door een verschuiving in de dominante frames. Deze verschuiving is waarschijnlijk het gevolg van een select aantal actoren dat sterke steun toonde voor deze frames en in meer of mindere mate succesvol was dit over te brengen naar de andere actoren. 2 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Theory.......................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Technological Innovation Systems ............................................................................................ 5 2.2 Discourse Theory and the Creation of Legitimacy..................................................................... 5 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Research design and Method .................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Gathering and analyzing data .................................................................................................... 7 4. Results ......................................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Data overview............................................................................................................................ 8 4.2 Actors examined ........................................................................................................................ 9 4.3 The creation of Legitimacy? .................................................................................................... 16 5. Conclusion & Discussion ............................................................................................................ 18 6. Bibliography............................................................................................................................... 19 7. Appendix.................................................................................................................................... 22 8.1 Tabel met labels en hun categorieen ...................................................................................... 22 8.2 Actor contribution ................................................................................................................... 23 8.3 Distribution of positive and negative arguments over time ................................................... 25 8.4 Actors arguments by category throughout the years. ................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 3 1. Introduction In the quest for sustainability the search for renewable energy sources has attracted enormous attention, both in the scientific and business environment. One of these new sustainable energy sources is wind power. Wind power provides a sustainable source of energy but not a very consistent one due to the variations in wind speed. Despite this fact, it could play an important part in our future energy system. For this reason the Dutch government has set the goal to have a total power capacity of 10.450 megawatt for on- and offshore wind energy in 2020. Promising as may be, the adoption of wind power is still low compared to the goals set in policy as the installed capacity is only roughly 2260 megawatt at this moment (Negro, Alkemade, & Hekkert, 2012; Rijksoverheid, 2013). To understand why, it is important to comprehend that an innovation does not depend solely on its physical features for success. Rather, innovations need sufficient and balanced integration in the business environment, regulation environment and the wider society to succeed (F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). This integration has not been very successful for wind power as developments are lagging and resistance has increased over the years (Breukers & Wolsink, 2007) despite the efforts of policy makers to stimulate it. Innovations thus depend heavily on their environment in which they are developed for their diffusion speed and direction, their application and chances on successful adoption (Bergek, Jacobsson, & Sandén, 2008; Negro et al., 2012). This environment is often referred to more or less the same way as Technological System or Technological Innovation System (TIS). TIS focusses on the innovative activities in the environment and is made up of several components and functions that influence the integration in the environment (Bergek et al., 2008). One of these functions describes the creation of legitimacy as a socio-political process through the actions of organizations and individuals as important for successful adoption because it aids the integration with the environment (Bergek et al., 2008; Frank W. Geels, Pieters, & Snelders, 2007; Hekkert & Negro, 2009). This gives power to the ability to create legitimacy because it gives control over the integration in the environment. This is done through articulating positive discourses around new technologies (F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). These discourses are “collections of interrelated texts that cohere in some way to produce both meanings and effects in the real world” ((Maguire & Hardy, 2009). Discourses act as public stages for the contested process in which actors aim to influence attitudes, feelings and opinions of other relevant actor to their own advantage. The groups that compete with each other use frames to portray the technology in a particular way and in turn influence the main discourse (F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). Partially responsible for the slow development of wind power is the failure of policy makers to gain insights in the motivations of the opposition. Assumed to be fueled by Nimbyism, the not-in-my-backyard type of arguments, the opposition has largely been disregarded, implying that their arguments are inherently less valid that those of proponents arguing for a greater good (Breukers & Wolsink, 2007). Understanding how in the discourse these processes take place over time in and which actors participate in it, can give useful insights into the Legitimacy function of the TIS. An increased understanding of this can identify causes for resistance which can help to increase the effectiveness of policy makers. Investigating the discourse around wind power in the Netherlands can thus increase our understanding in its integration and adoption process. This has not yet been done through the focus of legitimacy. Therefore, the main question of this research is: How did the legitimacy in the Dutch wind power discourse change since 2004 and what is the role of the actors therein? To answer this 4 question a database of relevant newspaper articles will be made and analyzed using Discourse Analysis. Newspapers are suited for this because they can give an indication of the perceived importance of wind power in the public sphere, the actors involved in the system and how legitimacy is created through texts. Discourse Analysis denies that there is an external reality waiting to be described. Rather, it sees reality as a construct of the way in which actors depict an object through frames in order to comprehend it. In this way the discourse forms a version of the object which comes to constitute it (Bryman, 2008). 2. Theory This chapter will start with a brief introduction into the Technological Innovation Systems (TIS) theory with a focus on one of its functions; Legitimacy. Following this will be an examination of Discourse theory explaining framing, some important propositions and with help of the five dimensions of legitimacy creation we will see how frames can be evaluated for their chances on success. 2.1 Technological Innovation Systems In the literature there are multiple definitions for technological innovation systems (TIS). Carlsson and Stankiewicz (1991) defined TIS as “a dynamic network of agents interacting in a specific economic/industrial area under a particular institutional infrastructure and involved in the generation, diffusion, and utilization of technology”. This theory derived from the Innovation System theory and also embraced the idea that the environment with its societal structure, actors and institutions determine technological change. This implies that every technology has its own unique TIS which, if favourable, enables it to diffuse more successfully (Hekkert & Negro, 2009). The components of a TIS are the actors, networks and institutions that help develop and diffuse a particular technology and the technology itself (Bergek et al., 2008). Determining whether or not a TIS is in favour or against a technology on more that only the outcome of possible success can be a challenge. The concept of system functions has been developed to provide a tool for this assessment which defines these functions as “… a contribution of a component or a set of components to a system’s performance.” (Hekkert & Negro, 2009). There is no definitive list of these functions in the literature but there are many similarities between them. In this research to following list of system functions will be adhered: Entrepreneurial Activities, Knowledge Development (Learning), Knowledge Diffusion through Networks, Guidance of the Search, Market Formation, Recourse Mobilisation and Creation of Legitimacy/Counteract Resistance to Change (Hekkert & Negro, 2009). Of special importance to this research is the Legitimacy function. According to Hekkert and Negro (2009) a new technology needs to embed itself in an incumbent regime or even overthrow it in order to be successful. Actors with interests in the technologies’ diffusion can oppose or propose it through the undermining or creation of legitimacy (Hekkert & Negro, 2009; Wieczorek et al., 2013). According to Bergek et al. (2008) the creation of legitimacy is a socio-political process through actions by various organizations and individuals. 2.2 Discourse Theory and the Creation of Legitimacy As mentioned in the introduction, discourse theory states that texts are integral to the creation of meaning, but do so only through interrelated collections of texts called discourses. These discourses are dynamic as more texts are produced, distributed and consumed over time (Maguire & Hardy, 2009). In order to support new technologies, actors aim to create legitimacy for them through 5 the production of texts which positively frame them. On the other hand opponents of this new technology try to undermine its legitimacy by framing it negatively. In the resulting framing struggle actors contest to influence the interpretations of reality among others on public stages at which they seek to strengthen their own frame and weaken those of their opponents (Fiss & Hirsch, 2005; F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). The actors in the discourse are typically labeled as either proponents or opponents resulting in an antagonistic dichotomy which is a reoccurring pattern around new technologies. This division is an effect of, inter alia, the increasing role of mass media which can easily use the contesting pro- and opponents for dramatic story lines (Rip & Talma, 1998). When frames acquire a broad enough support in the environment they can evolve into so called master frames, essentially becoming the discourse itself. Thus, discourses are more shared and generals way of thinking about a technology and frames are more specific because they focus on the meaning and interpretation of specific issues (F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). The power of discourses also arises from the fact that it unites individual actors in the system which allows for more coordination (Lovell, 2008). It is important to understand that in any discourse only a limited number of frames can be understood as meaningful, legitimate and powerful at any given point in time (Sengers, Raven, & Van Venrooij, 2010). The interaction between discourses and frames is an ongoing process in which the discourse sets the general terms and structures for a frames acceptance. However, salient frames can in turn influence the ways of talking and thinking in a discourse. This is closely intertwined with the concept of Legitimacy which is defined as “(…) a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions” (F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). The more a frame fits with the general assumptions of this system, the discourse, the more chance for it to become salient. Legitimacy is not a given fact; it is created through the actions of individuals and organizations in the discourse. Creating expectations and visions, and aligning with regulations and policy is central to the creation of legitimacy. However, legitimacy is also derived from the accumulation of actors that adhere a specific frame or discourse (Bergek et al., 2008). The support of investors, policy makers and the wider public is important for the technology to integrate in the environment. Legitimacy can gain the support of these important actors and secures the provision of recourses, protection or support for the technology (F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). Skilfully using the discourse as a cultural tool is an important ability for actors that wish to be successful at creating legitimacy for their frame (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001). 3. Methodology 3.1 Research design and Method In order to answer the research question in an appropriate manner the single case study with an explorative character has been used as a research design. This research strategy focuses on understanding the dynamics, in this case of legitimacy creation, present within a single setting over the years (Eisenhardt, 1989). This choice has been made because case studies are suited for exploratory research and provide rich content (F.W. Geels & Verhees, 2011). The unit of analysis in this research is the Dutch discourse about wind power focused on onshore projects. The distinction between onshore and offshore has been made because the onshore discourse sets itself apart by 6 conflicting national and local interests, involves a wide range of actors including a lot of individuals and is fueled by a good amount of projects already in existence. The offshore discourse on the other hand, involves fewer actors as it is more for the big players and is mostly a national matter in terms of approval and realization. In order to ensure the research remained in scope several boundaries have been made. Namely, only texts published from 2004 until the present (3-12-2013) in national and regional newspapers are included in the data search. Appropriate scientific literature has been sought in scientific databases using Scopus and Google Scholar. To focus this search, starting literature as provided by the supervisor, has been used in combination with keyword searches related to energy transitions, wind power, discourse analysis, cultural legitimacy and corporate political activity. Relevant articles are used to create a theoretical framework with which the research question can be answered. Relevant articles were also used for finding new literature by the use of snowballing and the cited-by function. 3.2 Gathering and analyzing data To acquire data about the Dutch wind power discourse, newspaper database LexisNexis has been used with the following search term: atleast2(windenergie) and park! and atleast2(windmolen or windturbine)) and Date(geq(31/12/2003) and leq(3/12/2013). This gives sufficient articles between 2004 and the present through the power search option with duplicate options on. This search term ensures that the articles cover the topic in sufficient depth and filters out those that merely mention wind power. The newspaper articles acquired through this search are carefully analyzed through coding in Nvivo. Selecting one statement at a time, labels are used and categorized to determine if the attitude against wind power is positive or negative, and who said what and where about wind power, using which type of arguments. These attitude labels fit with the proponent/opponent dichotomy found in discourses and will help determine if legitimacy for the wind power technology changed. Obstacles for the diffusion of wind power have been labeled because these are often used as a supportive condition of the argument made by the author (e.g. having a positive attitude but acknowledging that certain obstacles need to be overcome). A distinction between the onshore and offshore discourse has been applied so we can filter out the arguments from the onshore discourse. The specifics of these labels e.g. the actors name and the type of the argument were not set in stone as this allowed for additional labels to emerge during the research when it was deemed appropriate. The complete list of labels and their categories can be found with a short description in appendix 8.1 and the final list of label categories is presented in Table 1 below. A combination of these labels should give a good idea about the opinion of the author. E.g. the combination of Positive, Economic, Policy (Diffusion Obstacle) and Wind Power Industry would mean that a wind power business has a positive attitude against wind power because it provides economic benefits but points out that current policy is hampering its development. Type Date Newspaper Author Attitude Category 2004 […] 2013 Regional, National Energy Companies, Environmental Organizations, Individual Stakeholders, Local Municipalities & Policy Makers, Other, Politics, Provincial Policy Makers, Research and Consultancy, Wind Power Industry, Wind Power Lobby Groups Positive, Negative 7 Argument Diffusion Obstacle Alternative, Cooperation, Economic, Emotional, Environmental, Location, Necessity, Policy, Production of Sustainable Energy, Technological Economic, Location, Policy Table 1 The final database has been used to give insights into the framing struggle in the onshore wind power discourse by displaying the positive and negative arguments by type for each author over the years. This has been used to see which frames make up the discourse and who advocates it. 4. Results This chapter will start with an overview of the total contribution of arguments made per category and per actor over the years. This provides the opportunity to identify changes in the composition of the discourse over the years and different frame. Following, a closer look at the type of positive and negative arguments made by each actor in each year gives more detailed information about the frames they support in the discourse. Finally, a table will give an overview of the changes found in the actor examination. 4.1 Data overview In Chart 1 the contribution to the total arguments made ordered by category by all the actors is presented for each year. A change in the predominantly used arguments can be seen over the years so a shift in frames has occurred. In the early years (2004-2005) most arguments are focused on Technological, Production of Sustainable Energy, Location and Location (Diffusion Obstacle) and are predominantly positive (see chart 8.3 in appendix for attitude). In the last years (2011-2013) these arguments are barely visible anymore as the focus on Production of Sustainable Energy and Location (Diffusion Obstacle) arguments almost disappeared and the focus on Technological and Location arguments shrank considerable. The arguments are now focused on Alternative, Cooperation and especially Economic, Emotional and Policy (diffusion obstacle) and are overall slightly negative (see chart 8.3 in appendix for attitude). Herein we can identify two frames in which the proponents and opponents focus on different issues of wind power to influence legitimacy on those areas. These frames are: Frame 1: Focuses positive arguments on Production of Sustainable Energy, Location and Location (Diffusion Obstacle) and negative arguments on Technological. Frame 2: Focuses negative arguments on Emotional, Economic, and Alternative and positive arguments on Cooperation and Policy (Diffusion Obstacle). 8 To see what caused this shift, looking at the contribution to the total arguments made per actor in each year gives further insights. If the shift would be accommodated by a similar change in contributing actors it would be a clear sign where to look for the cause. However, such a change in actors is not clearly visible as all actors retain a relatively steady contribution to the discourse (see chart 8.1 in appendix 8.3). Thus, the accumulation of actors that support a specific frame is not the cause of the shift and it must come from a change in the arguments made by the actors instead. Total percentage of arguments per type 13 : Policy* (Diffusion Obstacle) 100% 12 : Location* (Diffucion Obstacle) 90% 11 : Economic* (Diffusion Obstacle) 80% 10 : Technological 70% 9 : Production of Sustainable Energy 60% 8 : Policy 50% 7 : Necessity 40% 6 : Location 5 : Environmental 30% 4 : Emotional 20% 3 : Economic 10% 2 : Cooperation 0% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 1 : Alternative Chart 1 4.2 Actors examined In this section each actor will be closer examined to see what contribution they have in the shift of frames. Each graph shows the contribution of positive argument per category to the total above the y-axis and the contribution of and negative arguments per category below the y-axis. The legend for the arguments is placed at the bottom of each page for readability. These findings are then summarized in a narrative in which the main contributors of the frames will be pointed out and a better understanding of the changes in legitimacy for both frames is given. 9 Energy Companies 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% Chart 2 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total This actor’s main focus lies with Production of Sustainable Energy, Economic and Technological arguments and has a predominantly positive attitude throughout the years. This means that the actor believes there are opportunities for economic benefits and that Wind Power is a suitable candidate for the production of sustainable energy. However, even though there are positive Technological arguments made, most of them are negative; mostly expressing concerns about the variation in electricity production due to unpredictable variance in wind speed. This concern is also expressed in some of the arguments for alternatives in the later years. Looking over time it becomes evident that the types of arguments changed from a focus on Technological and Production of Sustainable Energy fitting with Frame 1 to a focus on Alternative, Economic and Location fitting more with Frame 2. This actor’s main interest lies with the production and/or supply of energy. Wind power can thus be of good use as it provides green electricity, which sells at a higher price than grey electricity. But concerns about the varying output are present. Environmental Organizations 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 3 This actor’s focus changed from Environmental, Location, Production of Sustainable Energy and Technological arguments, fitting mostly with Frame 1, to a more narrow focus on Economic and Emotional arguments fitting more with Frame 2. This means that this actor believes wind power is 10 economically viable but has concerns about visual and noise impact in the later years. A comparable contribution of positive and negative attitudes is visible in both the early and later years. This actor’s main interest lies with the conservation of the environment in a sustainable manner. Wind power can thus be of good use for this actor but as it also disturbs nature due to the production of noise and the possible hazard for birds the overall attitude is mixed. Individual Stakeholders 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 4 The focus of this actor’s arguments remained relatively the same over time with mostly Emotional, Economic, Technological and Alternative arguments. A slight shift in focus can be seen in the last years as more Economic arguments are made. Overall this actor fits well with Frame 2. A shift in attitude can be seen from predominantly positive to negative. This means that this actor mostly has concerns about noise and visual nuisance and about the economic aspects of wind power technology, mostly the fact that it costs to must tax money for society. This actor is mostly made up of local residents of which the main interest lies with themselves. Most of them do not want to cope with the visual or audible nuisance of wind power in their vicinity. Although, some acknowledge the economic benefits of compensation plans, but those plans and actors are the exception rather than the rule. Local Municipalities & Policy Makers 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 5 11 This actor shows a clear shift in the focus of arguments over time. In the early years the focus lies on Location, Location (Diffusion Obstacle), Production of Sustainable Energy and Cooperation arguments fitting with Frame 1. This means that this actor is optimistic about the opportunity to produce sustainable energy, trusts that suitable locations are present and is positive about cooperating with different stakeholders. While the Location argument remained important, the later years show a shift in the focus of arguments to predominantly Emotional and Policy (Diffusion Obstacle) arguments fitting with Frame 2. A change in attitude can also be seen from predominantly positive to predominantly negative. This means that the trust in finding a suitable location for wind turbines has become more doubtful and that concerns about noise and visual nuisance have increased considerably. Policy is also recognized as an obstacle for the development of wind power in the later years. The main interest of this actor is to implement appropriate policy for wind power. Some municipalities have more plans for wind power that others which sometimes conflicts with adjacent municipalities or higher authorities resulting in conflicting policy, one of the main contributors to the category Policy (Diffusion Obstacle). The fact that this actor is also responsible for assigning locations for wind turbines explains the Location arguments. Other 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 6 This actor lacks a real focus on any of the two frames in the early years, although Technological and Production of Sustainable Energy arguments fitting with Frame 1 make a noteworthy contribution. However some signs of Frame 2 are also visible here in the form of Economic and Policy (Diffusion Obstacle) arguments. In the later years the contribution of Emotional and Economic arguments increases fitting with Frame 2 but so does the contribution of Technological and Production of Sustainable Energy arguments, fitting with Frame 1. A comparable contribution of positive and negative attitudes is visible over time. This means that this actor has concerns about the technology which is mostly expressed with the argument that a variation in wind speeds is a difficulty for the infrastructure. The actor also questions the economic feasibility but is positive about the amount of sustainable energy it can produce. As this is a collection of small incoherent actors like journalists, National Defense and unknown actors. As such, a clear interest for this actor is not present. 12 Politics 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 7 This actor shows a shift in the focus of arguments over the years. In the early years arguments focus on Necessity, Policy, Policy (Diffusion Obstacle) and Location (Diffusion Obstacle). This means that the actor is of the opinion that wind power is a necessity in order to increase or sustainable energy production. The reasoning behind this necessity mostly is the simple fact that the Dutch government needs to comply with European sustainability goals. Some concern about wind power policy also becomes apparent as it is recognized as a diffusion obstacle. This focus fits partially with Frame 1. In the later years the focus changed to Emotional, Economic, Necessity and Cooperation arguments, fitting with Frame 2. A change from a predominantly positive to a more negative attitude is also visible although most of the negative arguments are emotional. This means that concerns for visual and noise nuisance have become more important, mostly resulting from the fact that local politics are articulating the concerns about individual stakeholders. The main interest of this actor is to make and implement appropriate policy and policy goals for wind power. Because the Dutch government needs to comply with European sustainability goals this actor wants to speed up the development of wind power, resulting in the Necessity arguments. In the later years the Dutch government implemented laws that allowed them to have the final say in wind power initiatives that exceeded 100MW in capacity. There were some mentions that this caused more harm than good as for like blindly perusing policy goals does not lead to the best implementations of wind power leading to some of the negative Emotional arguments. 13 Provincial Policy Makers 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 8 This actor shows a focus on Location and, Location (Diffusion Obstacle) arguments throughout the years while Necessity and Production of Sustainable Energy arguments also maintain a steady but smaller contribution fitting largely with Frame 1. While the attitude is predominantly positive a clear shift in the arguments over time is not visible. Although a mention of the considerable contribution of Emotional arguments in the year 2012 fitting with Frame 2 is in place. This means that the actor is of the opinion that suitable locations are available and that wind power is necessary to fulfill policy goals. The main interests for this actor is implementing appropriate policy for wind power, and to comply with the overall policy goals of the Dutch government it is tasked to find suitable locations for wind turbines, explaining the Location arguments throughout the years and justifies these plans with the notion of the amount of sustainable energy that could be produced. Research and Consultancy 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 9 This actor shows a slight shift in focus from Technological, Economic and Production of Sustainable Energy arguments, which fits mostly to Frame 1 and a little to Frame 2, to a focus on Emotional, Cooperation and Technological arguments in the later years fitting with both Frame 1 and Frame 2. In the early years most arguments were promisis or doubts about the technology of wind power and predictions of feasibility. This technological doubt persists until the later years. Noteworthy is the 14 contribution of Economic arguments visible throughout the years except in the later ones which does not fit whith the shift to Frame 2. The attitude of the arguments shows significant flucuations throught the years but in total is equally divided. This actor does not have a clear interest as some of the researchers were in favor and others against wind power, both using conflicting predictions about costs, feasibility and the amount of the produced sustainable energy. Wind Power Industry 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 10 This actor shows a shift in focus from Production of Sustainable Energy and Emotional arguments, slightly fitting to Frame 1, to a focus on mainly Cooperation and in lesser extent Economic, Production of Sustainable Energy, Environmental, Location and Location (Diffusion Obstacle) which fits a little less with Frame 1. The Policy (Diffusion Obstacle) argument maintains a steady and considerable contribution throughout the years fitting with Frame 2. Noteworthy is the attitude which is almost exclusively positive as could be expected from this actor. This interest of this actor is clear, aiding the development of wind power. This actor consists of wind power business owners, individual farmers with wind power initiatives and others active in the wind power industry. From the argument it becomes clear that the industry is looking for cooperation with other stakeholders, mostly to take away the resistance most individual stakeholders have. One of the main arguments for wind power of this actor is the amount of sustainable energy that can be produced, often expressed in number of households that could be provided of electricity. 15 Wind Power Lobby Groups 100% 75% 50% 25% 0% -25% -50% -75% -100% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Chart 11 This actor makes no clear shift in the focus of arguments as Economic and Emotional arguments maintain a dominant contribution throughout the years fitting with Frame 2. A slight change in focus from Production of Sustainable Energy fitting with Frame 1, to Policy and Policy (Diffusion Obstacle) which fits Frame 2 is visible. The attitude fluctuates fast but steadily to a predominant negative attitude in the later years (also fits Frame 2). This actor consists of several proponents and opponents for wind power that are organized in lobby groups that range from permanent and very professional groups to temporary more amateur groups consisting of individual stakeholders. This actor partially represents individual stakeholder explaining the large amount of negative Economic and Emotional arguments. But there are also groups that favor wind power which articulate this through arguments of Production of Sustainable Energy. Policy (Diffusion Obstacle) is also an important aspect for this actor. 4.3 Changes in discourse and wind power legitimacy The examination of the separated actors breaks down the shift in the discourse into a more detailed view of the research period. We can see that some actors adhere one of the two frames to a great extent while others show support for a mix arguments from both of them. Based upon this distinction we can divide the actors into roughly three groups; those that show support for Frame 1 to a great extent (green shading in table 2), those that show support for Frame 2 to a great extent (red shading in table 2) and those that show a mix of support for both of the frames (no shading in table 2). In table 2 the actors are categorized into these groups for both the early and the later years showing the main supporters for both frames in these periods. Including is the overall attitude of the actor for wind power in both periods on the basis of positive +, indifferent +/- and negative - to see where legitimacy for wind power changed the most. The change in attitude over time is indicated in front of to the actors name by a ↑ for change to a more positive attitude, a ↓ for a change to a more negative attitude a — for no change in attitude. 16 Actor Early years support and attitude Later years support and attitude — Energy Companies F1 + F1 and F2 +/F2 and little F1 + F1 and some F2 + Some F1 +/Some F1 + F1 + F1 and some F2 +/Some F1 and some F2 + F2 and some F1 +/- + F2 +/F2 and little F1 Some F1 and some F2 Some F1 and some F2 +/Some F2 and Some F1 F1 and some F2 +/F1 and F2 +/F2 and Some F1 + F2 - — Environmental Organizations ↓ Individual Stakeholders ↓ Local Municipalities and Policy Makers — Other ↓ Politics ↓ Provincial Policy Makers — Research and Consultancy — Wind Power Industry ↓Wind Power Lobby Groups Table 2 From this table it becomes clear that Individual Stakeholders and Wind Power Lobby Groups are the main supporters of Frame 2 throughout the years and have both developed a strong negative attitude which contributes to the shift of frames in the discourse and the overall decrease of legitimacy. The actors Environmental Organizations, Local Municipalities and Policy Makers, Research and Consultancy and Wind Power Industry show support for both frames in the early years and drop some of the arguments for Frame 1 leaving more support for Frame 2 in the later years. Of these actors only Local Municipalities and Policy Makers changed in attitude from positive to negative. These actors contribute to the shift of frames and the change in legitimacy in the discourse, albeit to a lesser extent than the main supporters. The actors Energy Company and Provincial Policy Makers are the strongest supporters of Frame 1 with the actors Other and Politics following closely. Provincial Policy Makers stay more or less loyal to the frame 1 throughout the years but do adopt some arguments of Frame 2 in the later years and stay indifferent in attitude. Energy Companies adopt a whole different set of arguments in the later years which does not fit with any of the two frames in this research and stay positive in attitude. Other and Politics both adopt arguments from Frame 2 while the former stays indifferent and the latter changes from a positive attitude to a negative one. Table 2 clearly shows a weakened support for Frame 1 in the later years mostly replaced by support for Frame 2 as almost all actors adopted arguments that fit Frame 2 in the later years. The main supporters of Frame 1 stay mostly loyal as Provincial Policy Makers are the only ones that still show support for Frame 1 in the later years and as Energy Companies do not adopt Frame 2 at all but develop their own mix of arguments. An increased negative attitude is also visible with many actors except Energy Companies and the Wind Power Industry which remained positive and Environmental Organizations, Other and Research and Consultancy that remained indifferent. All other actors showed at least some increase in negative attitude over the years. 17 5. Conclusion & Discussion If wind power has to make a relevant contribution to the future of the sustainable energy production in the Netherlands the cause for its lagging development has to be found and solved. This research contributes to solving this problem through the investigation of the wind power discourse to gain insights into a particular function of the wind power TIS, Legitimacy. Legitimacy aids a successful integration in the environment in which an innovation develops. In this research legitimacy is measured by labeling newspaper articles to see inter alia, if the discourse is more positive or negative about wind power. The resulting database strengthened the understanding of discourse dynamics like framing struggles and provides the insights to answer the following question: How did the legitimacy in the Dutch wind power discourse change since 2004 and what is the role of the actors therein? In short, legitimacy in the whole Dutch wind power discourse decreased from slightly positive to slightly negative since 2004. A shift in the main frames accompanies this change for which a select group of actors seems responsible. Two groups of actors are identified as the main supporters for the two frames. Provincial Policy Makers and Energy Companies show the strong support for Frame 1 in both periods. Individual Stakeholders and Wind Power Lobby Groups show the strong support for Frame 2 in both periods. The other actors seem to be more open to persuasion than these two groups as in terms of arguments they are hovering somewhere between the two frames throughout the years. In the framing struggle the supporters of Frame 2 have shown to be more successful because almost all of the actors adapted arguments fitting with Frame 2 to a greater or lesser extent in the later years. The focus on different aspects of the wind power technology brought about by this change in frames is likely to be of influence on the decrease of legitimacy as the main arguments (Emotional and Economic) that are focused by Frame 2 in the later years are predominantly used in a negative manner throughout the years where as the main arguments of Frame 1 (Production of Sustainable Energy and Location) are used more positive (see chart 8.2 in appendix 8.2 for the total amount of positive and negative arguments made per type per actor). With this answer this research can help smoothing the development of- and policy for wind power in the Netherlands as the main causes for resistance have been identified. The industry for instance, can target the emotional arguments of individual stakeholders to reduce their concerns in that area. One of the shortcomings of this research is that the change in dominant frames cannot be exclusively held responsible for the change in legitimacy. Changes in wind power technology for instance could also have an influence. However no major changes in technology have been observed in this research other than the increase in wind turbine masts and rotor blades to enable higher production capacity. Although this may have fueled emotional arguments of individual stakeholders fearing the arrival of these big machines some also argued that the noise and visual impact they resulted in were minimal. Also it does not investigate how legitimacy is exactly created or undermined. Further research can use the five dimensions of legitimacy creation proposed by F.W. Geels and Verhees (2011) which are based on the work of Benford and Snow (2000). With these it is possible to investigate how likely different frames are to become salient and why. 18 6. Acknowledgments I would like to thank my super visors for feedbac 19 7. Bibliography Benford, R., & Snow, D. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual review of sociology, 26(2000), 611–639. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/223459 Bergek, A., Jacobsson, S., & Sandén, B. a. (2008). “Legitimation” and “development of positive externalities”: two key processes in the formation phase of technological innovation systems. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 20(5), 575–592. doi:10.1080/09537320802292768 Breukers, S., & Wolsink, M. (2007). Wind energy policies in the Netherlands: Institutional capacitybuilding for ecological modernisation. Environmental Politics, 16(1), 92–112. doi:10.1080/09644010601073838 Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods. Social research methods (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Carlsson, B., & Stankiewicz, R. (1991). On the nature, function and composition of technological systems. Journal of evolutionary economics, 93–118. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01224915 Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review, 14(4), 532–550. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/258557 Fiss, P. C., & Hirsch, P. M. (2005). The Discourse of Globalization: Framing and Sensemaking of an Emerging Concept. American Sociological Review, 70(1), 29–52. doi:10.1177/000312240507000103 Geels, F.W., & Verhees, B. (2011). Cultural legitimacy and framing struggles in innovation journeys: A cultural-performative perspective and a case study of Dutch nuclear energy (1945–1986). Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(6), 910–930. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2010.12.004 Geels, Frank W., Pieters, T., & Snelders, S. (2007). Cultural Enthusiasm, Resistance and the Societal Embedding of New Technologies: Psychotropic Drugs in the 20th Century. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 19(2), 145–165. doi:10.1080/09537320601168052 Hekkert, M. P., & Negro, S. O. (2009). Functions of innovation systems as a framework to understand sustainable technological change: Empirical evidence for earlier claims. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 76(4), 584–594. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2008.04.013 Lounsbury, M., & Glynn, M. A. (2001). Cultural entrepreneurship: stories, legitimacy, and the acquisition of resources. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6-7), 545–564. doi:10.1002/smj.188 Lovell, H. (2008). Discourse and innovation journeys: the case of low energy housing in the UK. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 20(5), 613–632. doi:10.1080/09537320802292883 Maguire, S., & Hardy, C. (2009). Discourse and Deinstitutionalization: the Decline of DDT. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 148–178. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2009.36461993 20 Negro, S. O., Alkemade, F., & Hekkert, M. P. (2012). Why does renewable energy diffuse so slowly? A review of innovation system problems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16(6), 3836–3846. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.03.043 Rijksoverheid. (2013). Duurzame Energie - Windenergie. Retrieved November 29, 2013, from http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/duurzame-energie/windenergie Rip, A., & Talma, A. (1998). Antagonistic patterns and new technologies. In Getting New Technologies Together (pp. 299–322). Berlin/New York. Retrieved from http://doc.utwente.nl/34704/1/K358____.PDF Sengers, F., Raven, R. P. J. M., & Van Venrooij, a. (2010). From riches to rags: Biofuels, media discourses, and resistance to sustainable energy technologies. Energy Policy, 38(9), 5013–5027. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.04.030 Wieczorek, A. J., Negro, S. O., Harmsen, R., Heimeriks, G. J., Luo, L., & Hekkert, M. P. (2013). A review of the European offshore wind innovation system. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 26, 294–306. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.05.045 21 8. Appendix 8.1 Tabel met labels en hun categorieen Type Category Discription Date 2004 […] 2013 Newspaper Regional National Author Energy Companies Environmental Organizations Individual Stakeholders Local Municipalities & Policy Makers Other Politics Provincial Policy Makers Research and Consultancy Wind Power Industry Wind Power Lobby Groups Attitude Positive Negative Argument Alternative Cooperation Economic Emotional Environmental Location Necessity Policy, Production of Sustainable Energy Technological Diffusion Economic obstacle Location Policy 22 8.2 Actor contribution Actor contribution to total arguments per year 100% 10 : Wind Power Lobby Groups and Foundations 9 : Wind Power Industry 90% 8 : Research and Consultancy 80% 7 : Provincial Policy Makers 70% 6 : Politic 60% 50% 5 : Other 40% 4 : Local Municipalities & Policy Makers 30% 20% 3 : Individual Stakeholders (Experience effects of Wind Power plans) 10% 2 : Environmental Organizations 0% 1 : Energy Companies 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Chart 8.1 23 Total percentage of positive and negative arguments per category per actor 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% -20% -40% -60% -80% Politics Wind Power Lobby Groups and Foundations Wind Power Industry Research and Consultancy neg arg per year Provincial Policy Makers neg arg per year Other neg arg per year Local Municipalities & Policy Makers neg arg per year Individual Stakholders neg arg per year Environmental neg arg per year Energy Companies neg arg per year 24 Chart 8.2 8.3 Distribution of positive and negative arguments over time Percentage of positive and negative arguments sorted by category 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% -20% -40% -60% -80% 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Year Chart 8.3 25