File - Madame Myers, McKinleyville High School

advertisement

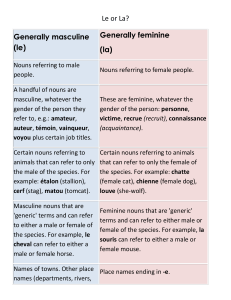

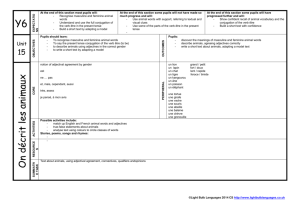

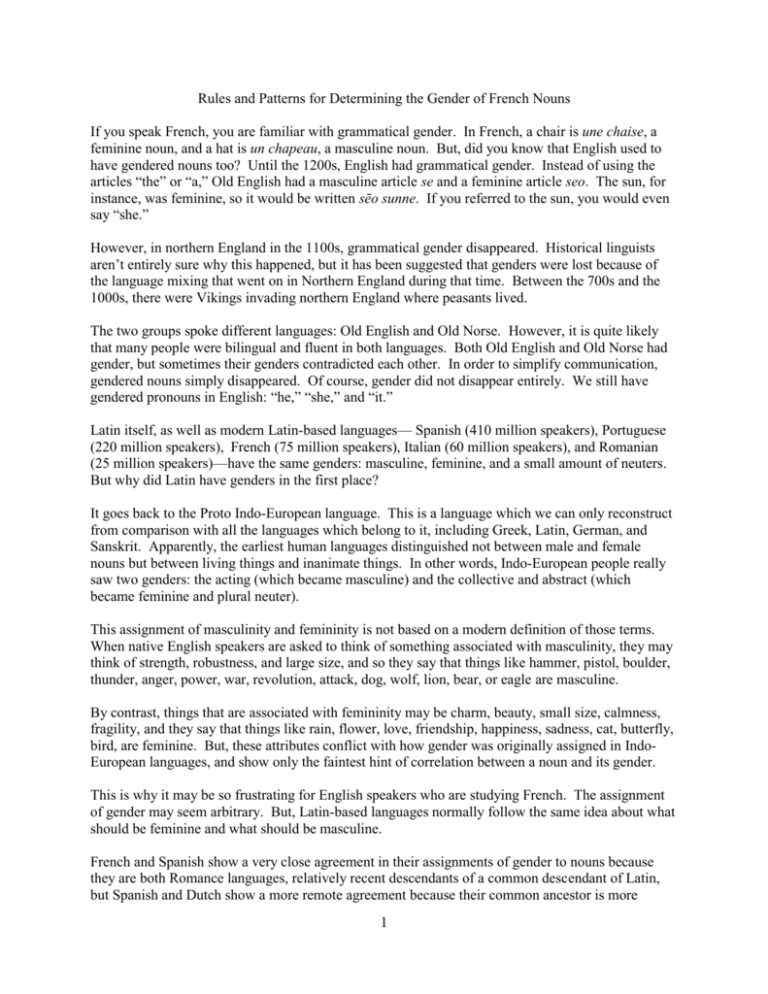

Rules and Patterns for Determining the Gender of French Nouns If you speak French, you are familiar with grammatical gender. In French, a chair is une chaise, a feminine noun, and a hat is un chapeau, a masculine noun. But, did you know that English used to have gendered nouns too? Until the 1200s, English had grammatical gender. Instead of using the articles “the” or “a,” Old English had a masculine article se and a feminine article seo. The sun, for instance, was feminine, so it would be written sēo sunne. If you referred to the sun, you would even say “she.” However, in northern England in the 1100s, grammatical gender disappeared. Historical linguists aren’t entirely sure why this happened, but it has been suggested that genders were lost because of the language mixing that went on in Northern England during that time. Between the 700s and the 1000s, there were Vikings invading northern England where peasants lived. The two groups spoke different languages: Old English and Old Norse. However, it is quite likely that many people were bilingual and fluent in both languages. Both Old English and Old Norse had gender, but sometimes their genders contradicted each other. In order to simplify communication, gendered nouns simply disappeared. Of course, gender did not disappear entirely. We still have gendered pronouns in English: “he,” “she,” and “it.” Latin itself, as well as modern Latin-based languages–– Spanish (410 million speakers), Portuguese (220 million speakers), French (75 million speakers), Italian (60 million speakers), and Romanian (25 million speakers)––have the same genders: masculine, feminine, and a small amount of neuters. But why did Latin have genders in the first place? It goes back to the Proto Indo-European language. This is a language which we can only reconstruct from comparison with all the languages which belong to it, including Greek, Latin, German, and Sanskrit. Apparently, the earliest human languages distinguished not between male and female nouns but between living things and inanimate things. In other words, Indo-European people really saw two genders: the acting (which became masculine) and the collective and abstract (which became feminine and plural neuter). This assignment of masculinity and femininity is not based on a modern definition of those terms. When native English speakers are asked to think of something associated with masculinity, they may think of strength, robustness, and large size, and so they say that things like hammer, pistol, boulder, thunder, anger, power, war, revolution, attack, dog, wolf, lion, bear, or eagle are masculine. By contrast, things that are associated with femininity may be charm, beauty, small size, calmness, fragility, and they say that things like rain, flower, love, friendship, happiness, sadness, cat, butterfly, bird, are feminine. But, these attributes conflict with how gender was originally assigned in IndoEuropean languages, and show only the faintest hint of correlation between a noun and its gender. This is why it may be so frustrating for English speakers who are studying French. The assignment of gender may seem arbitrary. But, Latin-based languages normally follow the same idea about what should be feminine and what should be masculine. French and Spanish show a very close agreement in their assignments of gender to nouns because they are both Romance languages, relatively recent descendants of a common descendant of Latin, but Spanish and Dutch show a more remote agreement because their common ancestor is more 1 ancient. Similarly, Spanish and Russian (a Slavic language) show an even more remote agreement, because their common ancestor language dates from even further back in the past. Interestingly, many words in Latin-based languages have the same gender. As long as the words share the same ancestral cognate, you can assume they are the same gender. However, when the word origins are different, the genders may be different as well. For example, the word for “book” in Latin is liber (masculine). In French, it is le livre (masculine), and in Spanish, it is el libro (masculine). But, have you ever wondered why there are two different genders for the French word livre? There is a number of French nouns which are identical in pronunciation (and often spelling as well) but which have different meanings depending on whether they are masculine or feminine. In Latin, the word for “pound” is libram, from libra, meaning “balance,” “pound,” “scales,” or “weights.” In French, it is la livre (feminine), and in Spanish, it is la libra (feminine). This is where the abbreviation “lb” for pound––as in 16 ounces––comes from. By contrast, the words for “thank you” are different because of their dissimilar origins. In Latin, one would say gratias to show gratitude. In Spanish, it’s gracias. But where did the French get merci? It’s from Latin mercedem, meaning “salary” or “reward” and, later, “price,” “favor,” or “mercy” given to someone when sparing them, as in Dieu merci, meaning “the grace of God” or “God willing.” Now, let’s move on from the historical explanations of genders to a more practical study of them. As your proficiency in the French grows, you’ll probably reach a point where you stop learning words with the article le or la alongside of them. And, there will inevitably be times when you can’t quite remember the gender of a word and could do with some kind of best guess. The information that follows gives some general patterns that will help you decide whether a word is masculine or feminine. Besides just memorizing noun endings, you can also spot masculine nouns by certain categories. For the most part, nouns included in the following categories are masculine: Names of trees: chêne (oak tree), olivier (olive tree), pommier (apple tree) Names of metals: or (gold), acier (steel), fer (iron) Names of metric units: mètre (a meter), kilo (a kilo), centimètre (centimeter) Names of colors: le rouge (red), le vert (green), le bleu (blue) Names of languages: le chinois (Chinese), l’allemand (German), le français (French) Nouns of English origin: tennis (tennis), parking (parking lot), football (soccer) The articles (le and l’) are in front of colors and languages above, because, without them, the French words would be adjectives instead of nouns. A number of more logical categories also help you spot those feminine nouns. For the most part, nouns included in the following categories are feminine: Names of sciences and school subjects: chimie (chemistry), histoire (history), and médecine (medical sciences). In particular, sciences and subjects ending in -graphie––like photographie (photography), géographie (geography), and chorégraphie (choreography) — are feminine. Names of automobiles: une Renault (a Renault), une Porsche (a Porsche), une Fiat (a Fiat) Names of businesses: boulangerie (bread shop), parfumerie (perfume shop), charcuterie (deli) 2 Common rules and patterns for deciding if a French noun is masculine or feminine. Generally masculine Nouns referring to male people A handful of nouns are masculine, whatever the gender of the person they refer to, e.g., amateur, auteur, témoin (witness), vainqueur (conqeror), voyou (hooligan, delinquant), plus certain job titles. Generally feminine Nouns referring to female people Certain nouns referring to animals that can refer to only the male of the species, e.g., étalon (stallion), cerf (stag), matou (tomcat). Certain nouns referring to animals that can refer to only the female of the species, e.g., chatte (female cat), chienne (female dog), louve (she-wolf). These are feminine, whatever the gender of the person: personne, victime, recrue (recruit), and connaissance (acquaintance). Masculine nouns that are generic terms and can refer to either a male or female of the species, e.g., le cheval can refer to either a male or female horse. Feminine nouns that are generic terms and can refer to either male or female of the species, e.g., la souris can refer to either a male or female mouse. Place names ending in -e. Common exception: la Names of towns. Other place names Franche-Comté (French department). (departments, rivers, countries) not ending in -e. Sometimes, town names, especially if they look or Common exceptions: le Mexique, le Combodge, sound feminine (e.g., Marseilles ending in -es), le Rhône, le Finistère (French department), le can be treated as feminine. This is quite rare, Zimbabwe (-e pronounced). though. Most other endings consisting of the formula Words ending in consonants vowel + consonant + e: -ine, -ise, -alle, -elle, -esse, -ette, etc. Nouns ending in -eur, generally derived from a verb, denoting people or machines carrying out an activity: aspirateur, facteur, ordinateur Figurative nouns ending in -eur, usually derived from an adjective: rougeur (redness), largeur (width), pâleur (paleness), couleur (color), horreur (horror), rumeur (rumor) Compound nouns of the form verb-noun: portemonnaie (wallet), pare-brise (windshield), tirebouchon (corkscrew) –– Below are some suffixes that usually indicate masculine nouns: -age Exceptions: la cage, une image, la nage, la page, la plage, la rage -b -ble Exceptions: une cible, une étable, une fable, une table -c Exception: la fac (apocope* of la faculté) -cle Exception: une boucle -d -de Exceptions: la bride, la merde, la méthode, la pinède; -ade, -nde, -ude endings -é Exceptions: la clé, la psyché; sé, té, and tié endings -eau Exceptions: l'eau, la peau -ège Exception: la Norvège -et -eur Note: this applies mainly to names of professions and mechanical/scientific things. 3 -f Exceptions: la soif, la clef, la nef -i Exceptions: la foi, la fourmi, la loi, la paroi -ing -isme -k -l -m Exception: la faim -me Exceptions: une alarme, une âme, une arme, la cime, la coutume, la crème, l'écume, une énigme, une estime, une ferme, une firme, une forme, une larme, une plume, une rame, une rime, mme ending -ment Exception: une jument -n Exceptions: la façon, la fin, la leçon, la main, la maman, la rançon; -son and -ion endings -o Exceptions: la dactylo, la dynamo, la libido, la météo, la moto, la steno (most of these areapocopes of longer feminine words) -oir -one -ou -p -r Exceptions: la chair, la cour, la cuiller, la mer, la tour (see feminine -eur) -s Exceptions: la brebis, la fois, une oasis, la souris, la vis -ste Exceptions: la liste, la modiste, la piste; names for people like un(e) artiste,or un(e) nudiste -t Exceptions: la dent, la dot, la forêt, la jument, la mort, la nuit, la part, la plupart -tre Exceptions: la fenêtre, une huître, la lettre, la montre, la rencontre, la vitre -u Exceptions: l'eau, la peau, la tribu, la vertu -x Exceptions: la croix, la noix, la paix, la toux, la voix * It is very common in French for long words to be abbreviated by dropping one or more syllables at the end, and then, in some instances, adding an -o. There are some apocopes which are so old that they are normal register, but most are informal or familiar, so use them with caution. Here are some suffixes that usually indicate feminine nouns: -ace -ade Exceptions: le grade, le jade, le stade -ale Exceptions: un châle, un pétale, un scandale -ance -be Exceptions: un cube, un globe, un microbe, un tube, un verbe -ce Exceptions: un artifice, un armistice, un appendice, le bénéfice, le caprice, le commerce, le dentifrice, le divorce, un exercice, un office, un orifice, un précipice, un prince, un sacrifice, un service, le silence, le solstice, le supplice, un vice -cé Exception: un crustacé -e Note: most countries and names that end in e are feminine. -ee Exception: un pedigree -ée Exceptions: un apogée, un lycée, un musée, un périgée, un trophée -esse -eur Note: this applies mainly to abstract qualities and emotions, except le bonheur, l'extérieur, l'honneur, l'intérieur, le malheur, le meilleur. Also see -eur in the masculine endings above. -fe Exception: le golfe -ie Exceptions: un incendie, le foie, le génie, le parapluie, le sosie -ière Exceptions: l'arrière, le cimetière, le derrière 4 -ine Exceptions: le capitaine, le domaine, le moine, le magazine, le patrimoine -ion Exceptions: un avion, un bastion, un billion, un camion, un cation, un dominion, un espion, un ion, un lampion, un lion, un million, le morpion, un pion, un scion, un scorpion, un trillion -ique Exceptions: un graphique, un périphérique -ire Exceptions: un auditoire, un commentaire, un dictionnaire, un directoire, un horaire, un itinéraire, l'ivoire, un laboratoire, un navire, un pourboire, le purgatoire, le répertoire, le salaire, le sommaire, le sourire, le territoire, le vocabulaire -ise -ite Exceptions: l'anthracite, un ermite, le granite, le graphite, le mérite, l'opposite, le plébiscite, un rite, un satellite, un site, un termite -lle Exceptions: le braille, un gorille, un intervalle, un mille, un portefeuille, le vaudeville, le vermicelle, le violoncelle -mme Exceptions: un dilemme, un gramme, un programme -nde Exception: le monde -nne -ole Exceptions: le contrôle, le monopole, le rôle, le symbole -rre Exceptions: le beurre, le parterre, le tonnerre, le verre -se Exceptions: un carosse, un colosse, le gypse, l'inverse, un malaise, un pamplemousse, un parebrise, le suspense -sé Exceptions: un exposé, un opposé -sion -son Exceptions: un blason, un blouson -té Exceptions: un arrêté, le comité, le comté, le côté, un député, un été, le pâté, le traité -tié -tion Exception: le bastion -ude Exceptions: le coude, un interlude, le prélude -ue Exception: un abaque -ule Exceptions: le préambule, le scrupule, le tentacule, le testicule, le véhicule, le ventricule, le vestibule -ure Exceptions: le centaure, le cyanure, le dinosaure, le murmure Where there is a conflict, rules to do with a word’s construction or function generally override rules to do with the word’s sound or ending. For example, pare-brise ends in the normally feminine ending -ise, but is of the verb-noun form, so it is masculine. The words trompette and clarinette have feminine endings, but when used to denote a person (“trumpet player” or “clarinette player”), they are masculine. 5