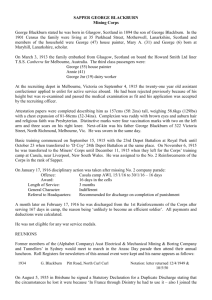

quotes

Citações (5)

1.

“In addition to judging the states of affairs the world contains, we may react to them. We form habits; we become committed to patterns of inference; we become affected, and form desires, attitudes and sentiments.

Such a reaction is ‘spread on’ the world, as Hume puts it in the Treatise, by talking and thinking as though the world contains states of affairs answering to such reactions.” (S. Blackburn, p. 470)

2.

“It is natural to put the projectivist thought, and Blackburn characteristically does put it, by saying that ethical commitments should not be understood as having truth-conditions. That would represent ethical remarks as statements about how things are, and according to projectivism they should be taken rather to express attitudes or sentiments. But quasi-realism is supposed to make room for all the trappings of realism, including the idea that the notion of truth applies after all to ethical remarks.” (J. McDowell, p. 153)

3.

“This only comes as a surprise if people feel: surely the projectivist denies that there is a right and wrong way to ‘spread’ attitudes on the world – no (‘real’) truth or falsity to generate a standard of correctness. But the fallacy is clear. The projective theory indeed denies that the standard of correctness derives from conformity to an antecedent reality. It does not follow that there is no other source for it. (…) A critic might say: ‘But can you really say that someone who is satisfied with a differently shaped sensibility, giving him different evaluations, is wrong, on this theory?’. The answer, of course, is that indeed I can. If his system is inferior, I will call it wrong, but not, of course, mean that it fails to conform to a cognized reality.” (S. Blackburn, pp. 479-480)

4.

“The problem about truth in ethics, viewed in this context, is not that it fails to be as the intuitionist realist supposes, so that establishing its availability requires a different metaphysical basis. The problem is that a question is raised whether our equipment for thinking ethically is suited only for mere attitudinizing – whether our ethical concepts are too sparse and crude for ethical thought to seem an exercise of reason, as it must if there is to be room in it for a substantial notion of truth.” (J. McDowell, p. 156)

5.

“The projectivist holds that our nature as moralists is well explained by regarding us as reacting to a reality which contains nothing in the way of values, duties, rights and so forth; a realist thinks it is well explained only by seeing us as able to perceive, cognize, intuit, an independent moral reality. He holds that the moral features of things are the parents of our sentiments, whereas the Humean holds that they are their children.” (S.

Blackburn, p. 471)

6.

“We have no point of vantage on the question what can be the case, that is, what can be a fact, external to the modes of thought and speech we know our way around in, with whatever understanding of what counts as better and worse execution of them our mastery of them can give us.” (J. McDowell, p. 164).

7.

“It seems to me that in McDowell’s development there is no room for a concept of moral truth which allows that a man who dissents from the herd may yet be right.” (S. Blackburn, p. 476)

Referências:

John McDowell, “Projection and Truth in Ethics”, in J. McDowell, Mind Value and Reality, Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1998.

Simon Blackburn, “Reply: rule-following and moral realism”, in A. Fisher e S. Kirchin (eds.), Arguing about Metaethics,

Routledge, 2006.