Jeungok Choi, PhD, MPH, RN is an Assistant Professor at the

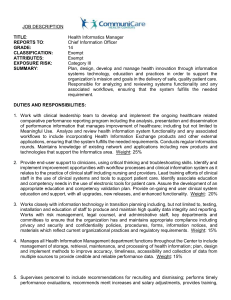

advertisement

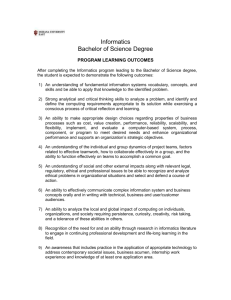

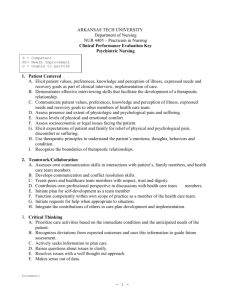

COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 1 Comparative Assessment of Informatics Competencies in Three Undergraduate Programs By Jeungok Choi, PhD, MPH, RN Citation: Choi, J. (June 2012). Comparative Assessment of Informatics Competencies in Three Undergraduate Programs. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics (OJNI), vol. 16 (2), Available at http://ojni.org/issues/?p=XXX Abstract This study was conducted to determine and compare the informatics competencies of students in three undergraduate tracks: Traditional Pre-Licensure, Registered Nurse (RN) to Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN), and Accelerated BSN. Data were collected from 131 students in fall 2011 using a 30-item Self-Assessment of Nursing Informatics Competencies Scale. Scale scores indicated that RN to BSN (mean=3.21) and Accelerated BSN (mean=3.01) students were competent in informatics, but not Traditional Pre-Licensure students (mean=2.82). Comparison of competency scores by track reveal that RN to BSN and Traditional Pre-Licensure students differed significantly in overall informatics competency (F(2, 92)=4.31, p=.02). This difference may reflect students’ different levels of clinical nursing experience and the learning format of each track. All students perceived they lacked competence in two subscale areas, “Applied computer skills” and “Clinical informatics role.” These findings provide insight about the strengths and weakness of the informatics competencies of nursing students and warrant attention from nurse educators when designing nursing curricula. Keywords: nursing informatics competencies, Self-Assessment of Nursing Informatics Competencies Scale, SANICS, undergraduate nursing students, RN to BSN, Accelerated BSN, Traditional Pre-Licensure COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 2 To ensure that nursing graduates are competent in the era of electronic healthcare delivery, it is essential to integrate informatics into clinical nursing curricula. Before nurse educators present informatics-related nursing content to the students, it is important to assess nursing students’ current level of informatics competencies (Gassert, 2008; Hebda & Calderone, 2010). Incorporating this assessment to gauge informatics competency is essential for student learning. The assessment provides feedback that can be used to adjust teaching methods or content of the informatics curriculum to students’ various needs. Despite the importance of assessing informatics competencies, few studies to date have reported informatics competencies of nursing students in two specific types of undergraduate programs, the Registered Nurse (RN) to Baccalaureate or Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) and Accelerated BSN programs. The RN to BSN program provides a baccalaureate nursing degree to licensed RNs with an associate degree (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2011a), and the Accelerated BSN program offers the BSN degree to students already holding a bachelor's degree in a non-nursing discipline (AACN, 2011b). To increase the proportion of baccalaureate-prepared nurses in the workforce to 80% by 2020, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine (2011), many nursing schools have added baccalaureate programs. Consequently, RN to BSN and Accelerated BSN programs are growing fast, contributing a significant portion of nurses to the current nursing workforce. Despite the growing number of students in these programs, however, only a few studies have reported their informatics competencies (Desjardins, Cook, Jenkins, & Bakken, 2005; Elder & Koehn, 2009; McDowell & Ma, 2007), and most studies combined students from these groups and reported the findings in an aggregate form (Elder & Koehn, 2009; McDowell & Ma, 2007). To date, no studies have compared informatics competencies of nursing students in the three baccalaureate programs: Traditional Pre-Licensure, RN to BSN, and Accelerated BSN. Students in these programs have different educational backgrounds and nursing practice experience; thus, they might have different preparation levels in informatics. For example, students in the Traditional Pre-Licensure program are generally younger than RNs who return to COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 3 nursing school to earn a BSN, and although they lack the nursing experience of RNs, they typically are more proficient with computers and computer applications. Accelerated BSN students have a baccalaureate or higher degree in another field and varied background knowledge of computers and computer applications. These students are similar to Traditional Pre-Licensure students in having little or no nursing experience, but many have been exposed to computers from their previous degrees and job experiences. Because nursing students across the undergraduate BSN options have such unique educational and nursing practice backgrounds, their knowledge of and capabilities related to nursing informatics competencies form a proverbial "mixed bag." Thus, the nursing curriculum needs to reflect this variation while advancing the students toward proficiency in informatics competencies. The purpose of this study was to determine and compare the informatics competencies of students in three undergraduate tracks (Traditional Pre-Licensure, RN to BSN, and Accelerated BSN). Baccalaureate Nursing Students’ Informatics Competencies According to Staggers and Gassert (2000), informatics competency is defined as the integration of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in the performance of various nursing informatics activities within prescribed four levels of nursing practice, beginning nurse, experienced nurse, informatics nurse specialist, and informatics innovator. Informatics competencies and recommended interventions to improve these competencies of baccalaureate nursing students have been well studied.. Overall, baccalaureate nursing students are competent (Desjardins, Cook, Jenkins, & Bakken, 2005) or have moderate informatics and technology knowledge, attitudes, and skills (Fetter, 2009; McDowell & Ma, 2007). Looking back to the 1990s, a study to assess computer literacy found baccalaureate nursing students’ had “some” experience in using microcomputers, personal computers, and WordPerfect as well as some keyboard skills (Gassert & McDowell, 1995). And in more recent studies, baccalaureate nursing students’ self-rated COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 4 competencies remained at a basic level, e.g., confidence in Internet searches, word processing, using email, and systems operations (Desjardins et al., 2005; Fetter, 2009; McDowell & Ma, 2007). Students rated themselves lowest on care documentation and planning, valuing informatics knowledge, skills development, and data entry competencies (Fetter, 2009). After formal training and hardware provision was given, modest improvements were found in basic computer knowledge and skills, but fewer gains in advanced skills and information literacy for nursing students at the baccalaureate (McDowell & Ma, 2007) and post- baccalaureate (Cole & Kelsey, 2004) levels. In two surveys of nurse executives and deans and directors of undergraduate and graduate programs, the nursing executives reported that new graduate nurses needed to be familiar with nursing-specific software such as computerized medicationadministration systems (McCannon & O'Neal, 2003) and recommended improving incorporation of these skills into nursing curricula (McNeil et al., 2003). Although nursing students nationwide reported positive attitudes toward technology, they reported little formal education in using technology applications (Maag, 2006). Furthermore, first-year baccalaureate nursing students rated themselves higher on their computer skills than their actual performance of those skills, suggesting that actual competency levels are lower than self-reported levels (Elder & Koehn, 2009). Most of these findings, however, were based on mixed groups of baccalaureate students from Traditional Pre-Licensure, RN to BSN, and Accelerated BSN programs (Elder & Koehn, 2009; McDowell & Ma, 2007), or only Accelerated BSN students (Desjardins et al., 2005). In summary, the review reveals that baccalaureate nursing students have competent (Desjardins, Cook, Jenkins, & Bakken, 2005) or moderate informatics and technology knowledge, attitudes, and skills (Cole & Kelsey, 2004; Fetter, 2009; McDowell & Ma, 2007). COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 5 These studies, however, included mixed groups of baccalaureate students from Traditional PreLicensure, RN to BSN, or Accelerated BSN students and reported the findings in an aggregate form. To date, no studies have compared informatics competencies of nursing students in the three baccalaureate programs. Thus, this study was undertaken to compare the informatics competencies of students in three undergraduate tracks (Traditional Pre-Licensure, RN to BSN, and Accelerated BSN). Methods Sample and Setting A convenience sample of 131 students at a northeastern state university enrolled at the school of nursing was used in the study. Students were aligned with one of three baccalaureate tracks: 78 Traditional Pre-Licensure students, 32 RN to BSN students, and 21Accelerated BSN students. Data Collection Data were collected on students’ informatics competencies by survey from September 2011 to January 2012. Competencies were assessed using the 30-item Self-Assessment of Nursing Informatics Competencies Scale (SANICS; Yoon, Yen, & Bakken, 2009). The SANICS was developed based on a set of informatics competency statements for beginning and experienced nurses (Staggers, Gassert, & Curran, 2001; Staggers, Gassert, & Curran, 2002), with additional items related to standardized terminologies, evidence-based practice, and wireless communications (Yoon et al., 2009). Each item is self-rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not competent) to 5 (expert). The SANICS has five subscales: “Clinical informatics role,” “Basic computer knowledge and skills,” “Applied computer skills: clinical informatics,” “Nursing informatics attitudes,” and “Wireless device skills.” The psychometric properties of the SANICS have been well established, with high internal consistency reliabilities ranging from .89 (wireless device skills) to .94 (basic computer knowledge and skills) (Yoon et al., 2009). Procedure COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 6 After receiving approval for the study by the author’s university institutional review board, a collection of student email addresses using LISTSERV was obtained from each track director. This list didn’t include specific identifiers, e.g., student names or individual email addresses. At the beginning of the semester, the students were introduced to the study and the SANICS via email. This email contained an embedded link to the Internet survey package, SurveyMonkey, which included the SANICS and demographic questions along with an online consent form. Students indicated consent to participate by returning the instrument via Internet to the SurveyMonkey secure site and checking off a box. Students were told the information was being collected for course evaluation and improvement purposes, and responses to the survey would have no effect on their current or future success in the course or program. In midNovember, students received a reminder email by LISTSERV to encourage study participation. Data Analysis Students’ informatics competencies and characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics (means and SDs). Differences in competencies by undergraduate track (Traditional vs. RN to BSN vs. Accelerated BSN) were analyzed by ANOVA. The internal consistency reliability of the SANICS was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale and its five subscales. SPSS, version 19.0 (Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses. Results Sample Characteristics The sample comprised 131 nursing students enrolled in the fall semester 2011 at one state university. The majority of students (59.5%) were in the Traditional Pre-Licensure track, 16.0% were in the Accelerated BSN track, and 24.4% were in the RN to BSN track. Of 283 students enrolled in the three tracks, 131 responded for a response rate of 46.3%. COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 7 The sample was predominantly female and from 20 to 30 years old (Table 1). Most respondents used a computer several times a day and had used computers >2 years (Table 1). The majority had worked in nursing <2 years (93.6% for Traditional Pre-Licensure, 76.2% for Accelerated BSN), except 43.8% of RN to BSN had worked 5 to 10 years. For details, see Table 1. Informatics Competencies The SANICS had high internal consistency reliabilities; Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was .95, and subscale alphas ranged from .93 for “Basic computer knowledge and skills” to .89 for “Clinical informatics role” and “Wireless device skills” (Table 2). With competence indicated by a minimum SANICS score of 3 (Yoon et al., 2009), RN to BSN and Accelerated BSN students were competent in informatics (mean=3.21, SD=.87 and mean 3.01, SD=.68, respectively), but not Traditional Pre-Licensure students (mean=2.82, SD=.55) (Table 2). Traditional Pre-Licensure students’ competency scores ranged from “Clinical informatics role” (mean=1.80, SD=.61) to “Basic computer knowledge and skills” (mean=3.32, SD=.61). Accelerated BSN and RN to BSN students reported their least competent area as “Applied computer skills” (mean=1.93, SD=.81 and mean=2.58, SD=1.08, respectively) and their most competent area as “Clinical informatics attitude” (mean=3.71, SD=.77 and mean=4.09, SD=.99, respectively). Comparison of Competency Scores by Undergraduate Track RN to BSN students reported the highest mean informatics competency score (mean=3.21, SD=.87), followed by Accelerated BSN (mean=3.01, SD=.68), and Traditional PreLicensure (mean=2.82, SD=.55) students. These scores differed significantly (ANOVA F(2, 92)=4.31, p=.02). Specifically, post hoc analysis indicates that RN to BSN students were significantly more competent (mean=3.21) than Traditional Pre-Licensure students (mean=2.82) (p=.02). When each subscale was considered, significant differences were found for three subscales, “Applied computer skills,” “Clinical informatics role,” and “Clinical informatics COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 8 attitude.” “Basic computer knowledge and skills” (p=.91) and “Wireless device skills” (p=.08) were not significant. Post hoc analysis shows the difference in all three subscale analyses lies between RN to BSN and Traditional Pre-Licensure students (all p<.001) (Table 2). Discussion Low Competence in Applied Computer Skills and Clinical Informatics Role RN to BSN and Accelerated BSN students were generally competent in informatics, but not Traditional Pre-Licensure students. Examination of participants’ SANICS subscale scores shows that, regardless of undergraduate track, students perceived they were competent in two areas, “Basic computer knowledge” and “Clinical informatics attitude.” The findings indicate that participating baccalaureate students were most confident in basic computer skills such as searching the Internet, word processing, systems-operations skills, as well as graphical and multimedia presentation, similar to previous reports (Desjardins et al., 2005; Fetter, 2009; Gassert & McDowell, 1995). Participants also fully recognized the value and positive impact of informatics on nurses and nursing practice, consistent with a nationwide survey of undergraduate and graduate nursing students (Maag, 2006). Students in all three baccalaureate tracks perceived that they lacked competence in “Applied computer skills” and “Clinical informatics role.” They were not confident in accessing or extracting information from clinical data sets (e.g., minimum data set) or as a clinician (nurse), participating in the selection process, designing, implementing, and evaluating systems, or seeking available resources to help ethical decisions in computing. These findings are not surprising considering the undergraduate students’ limited exposure to clinical nursing practice, but our findings indicate that these areas warrant attention in the design of informatics course curricula. One interesting finding is that RN to BSN and Accelerated BSN students perceived that they were competent in “Wireless device skills,” while the Traditional Pre-Licensure students did not. The findings indicate that Traditional Pre-Licensure students perceived themselves as not competent in locating and downloading resources and entering data using these wireless COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 9 devices. Interestingly, these students have been exposed to many technologies throughout primary and secondary school and were anticipated to be more likely to rate themselves as proficient in using wireless devices (personal digital assistants, smart phones). Comparison of Competency Scores among Students in Three Baccalaureate Tracks No significant differences were found in comparisons of either Traditional Pre-Licensure and Accelerated BSN or RN to BSN and Accelerated BSN. However, students in the RN to BSN track perceived themselves as more informatics competent than students in the Traditional PreLicensure track. These findings could not be compared to those in the literature because no relevant studies were found. However, our findings may reflect the greater nursing practice experience of RN to BSN students (62.6% had >5 years nursing experience), giving them greater exposure to informatics systems than Traditional Pre-Licensure students, of whom 74.4% had no nursing experience. These findings may also reflect the current online learning format of the RN to BSN track at our university, whereas the Traditional Pre-Licensure and Accelerated BSN tracks were taught in traditional classroom settings. The online learning format of the RN to BSN track is similar to the nationwide trend; more than 63.2% of 633 RN to BSN programs are offered at least partially online (AACN, 2011a). This learning format gives RN to BSN students greater exposure to computer use and applications than students in traditional classroom settings. When SANICS subscale scores were considered, RN to BSN and Traditional PreLicensure students differed significantly in three subscales: “Applied computer skills,” “Clinical informatics role,” and “Clinical informatics attitude.” For all three subscales, RN to BSN students perceived themselves more competent than the Traditional Pre-Licensure students. As discussed above, these findings may reflect students’ previous clinical nursing experience and the online learning format of their track. Further studies are needed to explore the differences in competencies for students in these three tracks. Future research is suggested to identify factors affecting competency (i.e., age, gender, nursing work experience, basic computer skills, or formal informatics education. etc.) in students in three undergraduate tracks. Identifying the predictors of informatics competency will help COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 10 develop appropriate strategies to prepare informatics competent graduates and further yield valuable insight for informatics curriculum development (Hwang & Park, 2011). Limitations This study had several limitations. First, an inherent limitation of any study in which the participants were volunteers and the response rate was low (46.3%), increasing the potential for non-response bias. Combined with convenience sampling, there is a potential for selection bias, which may threaten internal validity of the study. Second, the study generalizability was limited because participants were recruited from one northeastern university. Third, informatics competencies were measured by self-report, rather than actual informatics knowledge and skills. Thus, students’ actual informatics competencies might be lower due to over-reporting, as previously shown (Elder & Koehn, 2009). Further studies are suggested on informatics knowledge and skills, with direct measures of informatics competencies. Lastly, the sample distribution by programs is similar, but more Accelerated BSN students participated in this study compared to the AACN Enrollment data (AACN, 2011c) (16.0% vs. 5.3%). This may limit sample representativeness. Conclusion Establishing a baseline of informatics competencies in undergraduate nursing students is vital to planning informatics curricula and adequately preparing students to promote safe, evidence-based nursing care (Hebda & Calderone, 2010). The findings of this study indicate that RN to BSN and Accelerated BSN students were competent in informatics, but not Traditional Pre-Licensure students. Comparison of students in the three tracks reveal that RN to BSN and Traditional Pre-Licensure students differed significantly in overall informatics competency, which may reflect students’ experience in clinical nursing practice and the online learning format of each track. Students in all three tracks perceived that they were competent in “Basic computer knowledge” and “Clinical informatics attitude,” but not in “Applied computer skills” and “Clinical informatics role.” These findings on specific areas of informatics competency indicate topics for nurse educators to consider when designing an informatics curriculum. COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 11 References American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011b). Degree completion programs for registered nurses: RN to master's degree and RN to baccalaureate programs. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/DegreeComp.pdf American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011a). Accelerated baccalaureate and master’s degrees in nursing. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/mediarelations/AccelProgsGlance.pdf American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011c). The future of higher education in nursing American Association of Colleges of Nursing 2010 Annual Report. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/publications/annual-reports/AR2010.pdf Cole, I., & Kelsey, A. (2004). Computer and information literacy in post-qualifying education. Nurse Education in Practice, 4(3), 190-199. Desjardins, K., Cook, S., Jenkins, M., & Bakken, S. (2005). Effect of an informatics for evidence-based practice curriculum on nursing informatics competencies. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 74(11-12), 1012-1020. Elder, B. L., & Koehn, M. L. (2009). Assessment tool for nursing student computer competencies. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(3), 148-152. Fetter, M. S. (2009). Graduating nurses' self-evaluation of information technology competencies. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(2), 86-90. Gassert, C. A., & McDowell, D. (1995). Evaluating graduate and undergraduate nursing students' computer skills to determine the need to continue teaching computer literacy. Medinfo.MEDINFO, 8 Pt 2, 1370-1370. COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 12 Gassert, C. A. (2008). Technology and informatics competencies. Nursing Clinics of North America, 43(4), 507-521. Hwang, J. I., & Park, H. A. (2011). Factors associated with nurses' informatics competency. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 29(4), 256-262. Hebda, T., & Calderone, T. (2010). What nurse educators need to know about the TIGER initiative. Nurse Educator, 35(2), 56-60. Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of nursing: Focus on education. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing-Leading-Change-AdvancingHealth/Report-Brief-Education.aspx?page=1 Maag, M. (2006). Nursing students' attitudes toward technology: A national study. Nurse Educator, 31(3), 112-118. McCannon, M., & O'Neal, P. (2003). Results of a national survey indicating information technology skills needed by nurses at time of entry into the work force. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(8), 337-340. McDowell, D., & Ma, X. (2007). Computer literacy in baccalaureate nursing students during the last 8 years. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 25(1), 30-36. McNeil, B., Elfrink, V., Bickford, C., Pierce, S., Beyea, S., Averill, C., et al. (2003). Nursing information technology knowledge, skills, and preparation of student nurses, nursing faculty, and clinicians: A U.S. survey. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(8), 341-349. Staggers, N., & Gassert, C. (2000). Competencies for nursing informatics. In B. Carty (Ed.), Nursing informatics: Education for practice (pp. 17-34). New York: Springer. COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 13 Staggers, N., Gassert, C. A., & Curran, C. (2001). Informatics competencies for nurses at four levels of practice. Journal of Nursing Education, 40(7), 303-316. Staggers, N., Gassert, C., & Curran, C. (2002). A Delphi study to determine informatics competencies for nurses at four levels of practice. Nursing Research, 51(6), 383-390. Yoon, S., Yen, P., & Bakken, S. (2009). Psychometric properties of the Self-Assessment of Nursing Informatics Competencies Scale. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 146, 546-550. Table 1. Characteristics of Study Sample COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 14 Undergraduate Program Variables Gender Traditional RN-BSN Second BSN N % N % N % Female 74 96.1 30 93.8 21 100 Male 3 3.9 2 6.2 0 0 Race/Ethnicity Asian/Pacific Islander 6 7.7 4 12.5 1 4.8 Black, not Hispanic 2 2.6 1 3.1 0 0 Hispanic/Latino 2 2.6 1 3.1 1 4.8 White, not Hispanic 65 83.3 23 71.9 18 85.6 Other 3 3.8 3 9.4 1 4.8 Age 20-29 78 100 16 50.0 13 61.9 30-39 0 0 3 9.4 4 19.0 40-49 0 0 11 34.4 4 19.0 50 or older 0 0 2 6.3 0 0 Years of working in nursing Less than 2 years 73 93.6 4 12.4 16 76.2 2- 5 years 4 5.1 8 25.0 1 4.8 5-10 years 1 1.3 14 43.8 2 9.5 More than 10 years 0 0 6 18.8 2 9.5 Frequency of Computer Use Several times/day 77 98.7 27 84.4 21 100 Once/day 1 1.3 1 3.1 0 0 Several time/week 0 0 3 9.4 0 0 Several times/month 0 0 1 3.1 0 0 Length of computer use In the last six months 7 9.0 2 6.2 1 4.8 In the past two years 2 2.6 0 0 0 0 More than 2 years 69 88.5 30 93.8 20 95.2 COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 15 COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 16 Table 2. Summary of Competency Scores by Baccalaureate Track SANICS subscale Undergraduate Baccalaureate Track Traditional RN to BSN Accelerated BSN ANOVA* mean SD mean SD mean SD F p Total Scale (30 items, α=.95) 2.82 .55 3.21 .87 3.01 .68 4.31 .02 Basic computer knowledge and skills 3.32 .61 3.39 .91 3.36 .79 .09 .91 1.68 .73 2.58 1.08 1.93 .81 10.04 <.001 1.80 .61 2.89 .95 2.22 .79 18.73 <.001 3.31 .79 4.09 .99 3.71 .77 7.02 <.001 2.69 1.21 3.38 1.41 3.09 1.39 2.60 .08 (15 items, α=.93) Applied computer skills (4 items, α=.90) Clinical informatics role (5 items, α=.91) Clinical informatics attitude (4 items, α=.89) Wireless device skills (2 items, α=.89) *Comparison of Traditional Pre-Licensure vs. RN to BSN vs. Accelerated BSN α = Cronbach’s alpha COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF INFORMATICS COMPETENCIES 17 Author Bio: Jeungok Choi, PhD, MPH, RN is an Assistant Professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, School of Nursing. She had postdoctoral research training in Nursing and Biomedical Informatics at Columbia University School of Nursing sponsored by Reducing Health Disparities through Informatics Research Training Program (NINR T32). Her research focuses on web-based, pictograph-enhanced healthcare instructions for older adults with low literacy skills. She has completed several pilot studies for immigrant women and older adults with hip replacement surgery funded by Susan G. Komen for the Cure Massachusetts and Healey Endowment Grant University of Massachusetts, and is currently conducting two pilot projects which develop Web-based instructions for low literate older adults funded by American Nurses Foundation Association of Rehabilitation Nurses, and Sigma Theta Tau International, Inc. She currently teaches core DNP courses: Informatics for Nursing Practice, Intermediate Biostatistics, and Research Methodology in Nursing.