EATING DISORDERS

advertisement

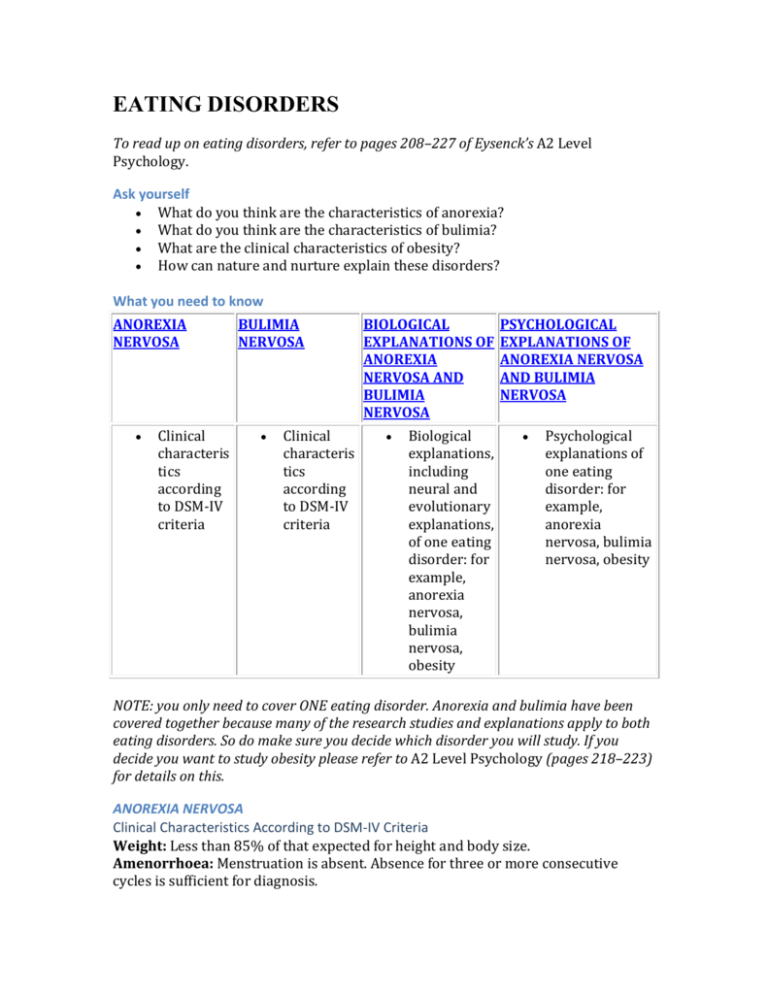

EATING DISORDERS To read up on eating disorders, refer to pages 208–227 of Eysenck’s A2 Level Psychology. Ask yourself What do you think are the characteristics of anorexia? What do you think are the characteristics of bulimia? What are the clinical characteristics of obesity? How can nature and nurture explain these disorders? What you need to know ANOREXIA NERVOSA Clinical characteris tics according to DSM-IV criteria BULIMIA NERVOSA Clinical characteris tics according to DSM-IV criteria BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA AND BULIMIA NERVOSA Biological explanations, including neural and evolutionary explanations, of one eating disorder: for example, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, obesity PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA AND BULIMIA NERVOSA Psychological explanations of one eating disorder: for example, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, obesity NOTE: you only need to cover ONE eating disorder. Anorexia and bulimia have been covered together because many of the research studies and explanations apply to both eating disorders. So do make sure you decide which disorder you will study. If you decide you want to study obesity please refer to A2 Level Psychology (pages 218–223) for details on this. ANOREXIA NERVOSA Clinical Characteristics According to DSM-IV Criteria Weight: Less than 85% of that expected for height and body size. Amenorrhoea: Menstruation is absent. Absence for three or more consecutive cycles is sufficient for diagnosis. Body-image distortion: Anorexics have a distorted idealised body image, and perception of their own body weight is also distorted as they fail to recognise their emaciation. Also, they overemphasise its importance to their self-esteem and minimise the dangers of being underweight. Anxiety: An intense fear of becoming fat, which is even more irrational given that they are considerably underweight. Physiological symptoms: Lowered body temperature, reduced bone mineral density, low blood pressure, slowed heart rate, irregular heart rhythms, hair loss and lanugo (soft downy hair on face, back, and arms). Anorexia is particularly prevalent among certain individuals. Over 90% are female, onset is usually during adolescence, and it is more common in middle-class than working-class individuals. It is more common in people from Western cultures, but is on the increase in populations in which it used to be rare (e.g. Black Americans) because of the pervasiveness of Westernisation into subcultures and Eastern cultures. BULIMIA NERVOSA Clinical Characteristics According to DSM-IV Criteria: Binge: When more food is eaten within a 2-hour period than most people would consume in that time, and the bulimic is not in control of their behaviour. Purge: Compensatory behaviours, such as vomiting, laxatives, exercise, or skipping meals to prevent weight being gained from the binge. Frequency: Binge eating and compensatory behaviour must occur twice a week or more, over a 3-month period, for diagnosis. Body image: Bulimics have a distorted idealised body image, and perception of their own body weight is also distorted as they fail to recognise that their weight falls within the normal range. Also, they overemphasise the importance of body image to their self-esteem. Physiological symptoms: Calluses on fingers due to vomiting, erosion of teeth enamel, lacerations in the lining of the mouth, and electrolyte imbalance, which can lead to cardiac arrest. Bulimia is prevalent in females and onset tends to be in their 20s. It is more common in people from Western cultures and is more common in middle-class than working class individuals. BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA AND BULIMIA NERVOSA Genetic Factors RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR GENETIC FACTORS Holland, Sicotte, and Treasure (1988, see A2 Level Psychology page 211) studied anorexia in monozygotic (MZ, identical) and dizygotic (DZ, fraternal) twins. A difference was sought between MZ and DZ twins, because MZ are 100% genetically identical whereas DZ have only 50% of their genes in common. Thus, there should be a higher concordance rate for MZ than DZ twins if there is a genetic basis to anorexia nervosa. A significant difference was found as there was a much higher concordance rate of anorexia for MZ (56%—9 of 16) than DZ (7%—1 of 14) twins. Further findings were that in three cases in which the non-diagnosed twin did not have anorexia they were diagnosed with other psychiatric illnesses and two had minor eating disorders. Fairburn and Harrison’s (2003, see A2 Level Psychology page 212) findings show a concordance rate of about 55% for MZ twins and 5% for DZ twins for anorexia. Wade et al.’s (2008, see A2 Level Psychology page 212) research into the link between temperament and anorexia supports a genetic basis because temperament is known to be genetically controlled. They found that perfectionism, a high need for order, and sensitivity to praise and reward were linked to anorexia. Whilst such traits could be the result of family experience and culture, the researchers feel these shared risk factors must be, in part at least, genetic. Kendler et al.’s (1991, see A2 Level Psychology page 211) study on bulimia found concordances of 23% for MZ and 9% for DZ twins. This supports a genetic basis to bulimia. Monteleone et al.’s (2007, see A2 Level Psychology page 213) findings suggest that a gene involved in serotonin transmission, whilst not actually causing bulimia, does seem to be involved in the predisposition to bulimia. Nisoli et al. (2007, see A2 Level Psychology page 213) established that in a group of over 100 Italian participants suffering from anorexia, bulimia, or obesity that a gene previously associated with other psychopathologies such as alcohol and drug abuse, the TaqA1 allele, is present in those vulnerable to eating disorders. RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST GENETIC FACTORS The evidence for a genetic basis ignores the role of environmental factors or nurture in causing anorexia or bulimia. The environment certainly plays a role, because the concordance rate was for MZ twins are not even close to 100%, which they would be if eating disorders were exclusively due to genetic factors. Key environmental factors include the fact that MZ twins often experience a more similar environment and are treated more similarly than DZ twins because they look and behave more alike (Loehlin & Nichols, 1976, see A2 Level Psychology page 211). However, nurture doesn’t fully account for the considerable difference found between MZ and DZ twins. The recent dramatic increase in sufferers from eating disorders cannot be explained in genetic terms because there have been no major genetic changes over the past 20–30 years. Garner and Fairburn (1988, see A2 Level Psychology page 210) reported figures from an eating disorder centre in Canada. The number of patients treated for bulimia nervosa increased from 15 in 1979 to over 140 in 1986. The large differences in the incidence of eating disorders across cultures (Comer, 2001, see A2 Level Psychology page 211) can also not be accounted for by genetic factors. Wade et al.’s (2007 see A2 Level Psychology page 212) research on Australian female twins showed that the families of anorexics and bulimics made frequent comments about weight and shape whilst they were growing up; and higher levels of paternal protection were associated with anorexia than with bulimia whilst higher levels of parental expectation were associated with bulimia than with anorexia. Thus, this shows the role of nurture and so is evidence that anorexia is not just due to genetics. Research into male anorexics is quite rare but one study into this suggests a psychological basis and so challenges a purely genetic explanation. Chambry and Eilles (2006, see A2 Level Psychology page 212) found that there is a higher frequency of homosexual behaviour than in female anorexics and so they have linked a vulnerable sexual identity to male anorexia. Fairburn and Harrison’s (2003, see A2 Level Psychology page 212) findings show a concordance rate of 35% and 30% for MZ and DZ twins respectively for bulimia, which does not suggest a strong genetic basis for bulimia, as if this was the case the concordance for MZ twins with identical genes should be considerably higher than that for DZ who only share 50% of their genes. EVALUATION OF RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO GENETIC FACTORS Twin studies provide strong genetic evidence. As the MZ twins are genetically identical whilst DZ twins are no more alike than ordinary siblings, this supports the involvement of genetic factors. If these were not important, and instead nurture was the key determinant, then there should be no difference in the concordance rates between MZ and DZ twins. Methodological weaknesses of concordance studies. The evidence from twin studies must be considered cautiously because diagnosis of the second twin may be biased by the knowledge that the first twin has been diagnosed. Reliability. The concordance rates for anorexia are relatively consistent across studies, which supports the reliability of the research and consequently the validity of a genetic basis to anorexia. The concordances for bulimia are not so reliable given that the difference between MZ and DZ twins is 14% in Kendler et al.’s (1991) study and yet only 5% in Fairburn and Harrison’s (2003) study and so the lack of reliability suggests there is not such a strong genetic basis for bulimia as for anorexia. Not 100% concordance rates. Whilst exactly 100% concordances are unlikely, as even in MZ twins with 100% the same genes there may be some genetic variation due to epigenetics (i.e. the interaction of nurture in the switching on or off of the genes), the research shows that the concordances are not even close to 100%, which we would expect in identical twins if genes were the main cause of eating disorders. The fact that there are no 100% concordance rates suggests that other factors must be involved. Small samples. The data on much of the genetics research is from clinic samples, which are obviously not representative of the general population, particularly because such samples tend to be quite small (often fewer than 10) because of the difficulty of finding twins where one or both have an eating disorder, which means that population validity is limited. Environmental factors. The fact that concordance rates increase with genetic relatedness may be explained by the fact that this is because they are also likely to spend more time together, which means environmental factors may be influential. Predispose not cause. As the disorder is not wholly genetic this leads to the conclusion that genes alone do not cause eating disorders; instead they predispose, i.e. place the individual at a greater risk for developing the disorder. See the diathesis–stress model in the “So what does this mean?” concluding section to biological explanations for a more comprehensive account of how genes predispose, rather than cause, the disorders. A common genetic basis. Nisoli et al.’s (2007) findings that there is a common gene associated with a number of psychopathologies has strength in that a specific gene, the TaqA1 is identified and this may have useful implications in terms of gene therapy. However, there is a lack of explanatory power because it does not explain why one person develops a drug abuse problem and the other an eating disorder. Biochemical Factors RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR BIOCHEMICAL FACTORS Bachner-Melman et al. (2007, see A2 Level Psychology page 224) have established that three genes associated with anorexia are also associated with the personality trait perfectionism as measured on the Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS), and that these genes have neural effects on dopamine receptors and receptors for other neurochemicals such as growth factor. Thus, genes and biochemistry may interact. Carrasco et al. (2000, see A2 Level Psychology page 211) found that bulimics tend to have low serotonin activity. Bingeing on starchy foods containing carbohydrates can increase serotonin levels in the brain and improve mood, and so may explain why bulimics have the urge to binge eat. Research has also linked anorexia to high levels of serotonin. High levels of serotonin suppress appetite and increase anxiety and obsessive behaviour, which of course are characteristics of anorexia. Restricting food may be a form of “self-help” because serotonin levels will drop as a result of less food. Molecular genetic research is focusing on serotonin-related genes as serotonin is known to be important in regulating eating and mood, and so this suggest that genes and biochemicals interact in the aetiology of eating disorders. RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST BIOCHEMICAL FACTORS Patients with bulimia nervosa do not focus specifically on foods containing carbohydrates when they binge (Barlow & Durand, 1995, see A2 Level Psychology page 211). EVALUATION OF RESEARCH INTO BIOCHEMICAL FACTORS Cause, effect, or correlate? The biochemical imbalances are difficult to interpret, as it is difficult to determine if they are a cause or a consequence of having the disorder. For example, low levels of serotonin in anorexia may be due to insufficient food, or a consequence of the binge–purge cycle in bulimics, and so biochemical imbalance may be an effect rather than a cause of the disorder. It is only possible to conclude that biochemical imbalances are associated with eating disorders rather than a being a cause. Brain Structural Abnormality RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR BRAIN STRUCTURAL ABNORMALITY Hypothalamus dysfunction may be an explanation as this part of the brain is involved in the control of hunger. In fact the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) and the lateral hypothalamus (LH) are known as the “stop/start” mechanisms for hunger. They maintain weight homeostasis because the LH or “start switch” produces feelings of hunger and the VMH or “stop switch” suppresses feelings of hunger. Anorexics may have an abnormality in the LH, which produces feelings of hunger, and bulimics and obese individuals may have an abnormality in the VMH, which suppresses hunger. EVALUATION OF RESEARCH INTO BRAIN STRUCTURAL ABNORMALITY Cause, effect, or correlate? Causation is also an issue with the brain structural abnormality explanation because we cannot be sure if the abnormality is a cause or consequence of the disorder. This means causation cannot be established and so it is only possible to conclude that brain structural abnormalities are associated with eating disorders rather than being a cause. OVERALL EVALUATION OF BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS Scientific and objective evidence. The biochemical levels and brain structural abnormality provide objective evidence because such measures are not very open to opinion or bias. Thus, the evidence for the biological explanations has scientific validity, which means we can have more confidence in the findings. Deterministic. The biological explanations can be criticised as biologically deterministic because they ignore the free will and ability of individuals to control their own behaviour. The explanations suggest that if someone has particular genes or biochemical imbalances they will inevitably have an eating disorder, which ignores the individual’s motivation to resist or overcome eating disorder. Reductionist. The biological explanations try to explain behaviour using only one factor (biology) and so they are reductionist, which means they are too simplistic and as a consequence the explanations lack conviction. For example, the explanation that hypothalamus dysfunction may explain eating disorders is oversimplified as motivation and cognition can override this to some extent. Do not account for social and psychological factors. The biological explanations cannot account for the psychological aspects of eating disorders, such as the distorted body image and intense fear of weight gain. This is because the explanations ignore nurture, i.e. psychological and social factors. For example, eating may be due to motivational rather than physical factors. Similarly, biological explanations cannot explain the recent rapid rise in eating disorders. Social and cultural factors are more likely to explain this rise. Evolutionary Explanations Evolution predicts that if a behaviour exists over time then it must in some way be adaptive (i.e. increase chances of survival) to have stayed in the gene pool. If it was not adaptive it would have been weeded out through natural selection (the process by which genes advantageous to survival are selected into the gene pool. This suggests that anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity are in some way adaptive. Evolutionary explanations of food preferences have been covered above so do refer back to this section as it provides insight into the evolutionary explanations of eating disorder. EVIDENCE FOR EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATIONS OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA Inclusive fitness refers to the idea that behaviour may have evolved because it benefits the group rather than the individual. The group members would be related and so relatives would thrive at the expense of the individual. The individual would be less likely to reproduce and so instead would achieve reproductive fitness because the genes shared with the relatives would be more likely to survive. This may explain anorexia as if one member of the group ate very little then this would leave more food available for other group members and this would be advantageous, particularly in hard times when food became scarce. Another evolutionary hypothesis relates to rank theory, which is the idea that the human struggle for survival results in a great deal of conflict. The anorectic behaviour is a sign of accepting defeat after some sort of conflict and so assuming a low position in the rank (Gatward, 2007, see A2 Level Psychology page 214). The anorexia signals that the individual is weak and no longer a threat. EVIDENCE AGAINST EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATIONS OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA It seems highly implausible that anorexia is adaptive. It seems more maladaptive now so surely it would have been even more so in the more harsh conditions of our hunter-gatherer world? The anorexic would be weak and so a liability to the group. It seems unlikely that the gain in food to the group would outweigh the time and care needed to support the anorexic when very close to death. Similarly, starving oneself seems an extreme way of showing submission, which again suggests the hypothesis lacks validity. EVIDENCE FOR EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATIONS OF BULIMIA NERVOSA The binge aspect of bulimia can be explained as adaptive because our huntergatherer ancestors could not be sure when they would next eat as this depended on the success of the hunt, and foods gathered would perish very quickly. Individuals that could feast when food was plentiful and store this as body fat would be better able to survive in times of famine. Clearly this would increase chances of survival and, particularly in the case of females, it would increase chances of reproduction as pregnancy and lactation require fat reserves. Then a mutation could have linked the gene for bingeing with one that causes the stomach to empty quickly if it became very full, thus producing the purging behaviours. EVIDENCE AGAINST EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATIONS OF BULIMIA NERVOSA Bulimia like anorexia seems more maladaptive than adaptive. The purging aspect could never be a healthy behaviour and so could not be called successful. If genetic mutation caused the purging behaviour then it is not due to evolution, which only accounts for behaviour evolving because it is adaptive. Maybe all aspects of bulimia are due to genetic mutation rather than evolution of the disorder as an adaptive behaviour. EVALUATION OF EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATIONS Maladaptive rather than adaptive. Evolutionary explanations seem highly implausible. The idea that eating disorders are somehow beneficial in some way is counter-intuitive to the extremely maladaptive nature of them. Mental disorders are often very disturbing to the patient and may severely disrupt their everyday functioning, thus we shouldn’t exaggerate any adaptive value they may have.Why should a disorder be adaptive? It seems a real contradiction in terms. The eating disorders would limit survival and reproduction. Conjecture—evolutionary stories? Deciding what was adaptive in our evolutionary past is highly speculative. Consequently, they have been criticised as evolutionary stories because we have no way of establishing if they are true or not. Post hoc and so lack scientific validity. We cannot research our evolutionary past and so the evolutionary explanations are post-hoc (made up after the event) hypotheses. The evidence we do have from fossils is very limited especially in terms of human behaviour. They cannot tell us if bulimia or anorexia were adaptive for our evolutionary ancestors. Thus, whilst evolution itself is fact, the evolutionary explanations of human behaviour are not, they are just speculation and cannot be verified or falsified. Karl Popper identifies falsification as a key criterion of science and so on this basis the explanations lack scientific validity. Reductionist and deterministic. Evolutionary theories are reductionist as they focus on one factor only (the gene) when other emotional, social, cognitive, behavioural, and developmental factors are highly relevant to the aetiology of eating disorders. They are oversimplified accounts at best. They are also deterministic as they suggest that the genes control behaviour, which ignores the free will of the individual. See the overall evaluation of biological explanations for further elaboration of these criticisms. Psychological explanations. The psychological explanations of eating disorders are counter-perspectives and are ignored by evolution. Moreover, they may account for why adaptive behaviours have become distorted. For example, bingeing may have evolved as an adaptive response but sociopsychological factors may explain why today such food consumption creates anxiety and so is followed by purging. Nature/nurture. The evolutionary explanations overemphasise the role of nature and ignore nurture. It is not a question of nature or nurture, as indisputably an interactionist perspective must be taken. However, as the evolutionary explanations ignore nurture this is a key weakness. Genetic transmission may not be adaptive. Eating disorders may not have been weeded out because they are recessive, i.e. a person may carry the gene but not exhibit the disorder, which only manifests when both parents carry recessive alleles. Thus, it is naturally selected not because of increased fitness but because it is difficult to eliminate, as recessive genes do not affect the individual’s reproductive fitness. Another explanation is that nature did not create perfect organisms. “Bottlenecks” in human evolution (when the population was very small) meant genetic mutations could not be weeded out in the usual way. Both of these possibilities, recessive alleles and “bottlenecks”, suggest the disorders have been transmitted in spite of being maladaptive and so challenge the evolutionary explanation that eating disorders are adaptive. SO WHAT DOES THIS MEAN? It is hard to separate out the influence of nature and nurture or environment in the development of eating disorders. It is oversimplified and reductionist to consider only one factor, biology, as a basis for anorexia or bulimia. The compromise position of the diathesis–stress model is more convincing than biological explanations alone. According to this, the genes (nature) load the gun, but it is the environment (nurture) that pulls the trigger. This means an individual may inherit a vulnerability to a disorder (particular genes that cause biochemical and brain structural abnormality: the diathesis), which places the individual at greater risk of developing the disorder. But it is not inevitable that the disorder will develop because it depends on the interaction of the diathesis with psycho-social stressors. Thus, psychological and biological explanations, (i.e. a multi-perspective) are needed to fully explain eating disorders. OVER TO YOU 1. Outline and evaluate biological explanations of one eating disorder. (25 marks) 2(a). Outline the clinical characteristics of one eating disorder. (5 marks) 2(b). Critically consider the biological explanations of one eating disorder. (20 marks) PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA AND BULIMIA NERVOSA Psychodynamic Explanations RESEARCH/THEORY The psychodynamic approach suggests unconscious conflicts from childhood may be the basis of eating disorder. The fact that the disorder is mostly found in adolescent girls suggests that anorexia might be due to fear of increasing sexual desires; denying oneself food is a way of repressing these sexual desires. Another fear may be pregnancy, where eating may be seen as a form of oral impregnation. Starvation is a way to avoid becoming pregnant because one of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa is amenorrhoea (the absence of menstruation). Another psychodynamic explanation suggests anorexia is a way to arrest sexual development because the anorexic has an unconscious desire to remain pre-pubescent. Their weight loss prevents them from developing the body shape associated with adult females, and thus allows them to preserve the illusion that they are still children. Family systems theory (Minuchin et al., 1978, see A2 Level Psychology page 215) suggests that the families of anorexics are characterised by conflict, overprotectiveness, rigidity, and enmeshment, meaning that none of the members of the family has a clear identity because everything is done together. The enmeshed family is smothering and can lead to a lack of identity. The child rebels against the family by refusing to eat. It is an attempt to gain independence and take control. Family conflicts have also been identified in families with a child showing signs of bulimia or anorexia. The number of negative interactions outweighs the positive interactions. It is also suggested that the anorexia is a result of parental conflicts because these are reduced by the need to attend to the anorexic child. Bruch (1991, see A2 Level Psychology page 215) proposed that eating disorders are due to the individual’s struggle for identity and autonomy. There is conflict with the mother because she has never been able to identify and successfully meet the needs of the sufferer. This is linked to food being used as a comfort. Anorexia is a rejection of food as a reward as it is not used for comfort, whereas bulimia involves using food as a reward to oneself. This also suggests that the eating disorder is a way to take control. RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST PSYCHODYNAMIC THEORY Hsu (1990, see A2 Level Psychology page 215) reported that families with an anorexic child tend to deny or ignore conflicts and to blame other people for their problems. The problem is that these parental conflicts may be more a result of having an anorexic child than a cause of anorexia. EVALUATION OF PSYCHDYNAMIC EXPLANATIONS Conflict—cause or consequence? Family conflicts may be more a result of having a family member suffering with an eating disorder, and so may be an effect rather than a cause. Furthermore, many families have conflicts but this does not necessarily result in abnormality, nor does it explain why the disorders occur in women more than men. Generalisability. This is an issue because the psychodynamic explanations based on sexual development only relate to adolescent girls. Anorexia is more common in adolescent girls is not exclusive to them, so explanations cannot explain anorexia in boys or adults. Psychodynamic explanations are subjective (not objective). They are based on clinical interviews and case studies, which are vulnerable to researcher bias. Because they are theory rather than evidence, this means they are opinion rather than fact: they have not been tested rigorously and objectively. Psychodynamic concepts are vague and hard to define so they cannot be operationalised. This means they cannot be tested empirically and so can neither be falsified nor verified. Nobody can prove they are right, but they also cannot be proven to be wrong. This means the explanations lack scientific validity because Popper identified falsifiability as an important criterion of science. Cognitive Explanations RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR COGNITIVE EXPLANATIONS People with eating disorders have a distorted view of their own body image and what an ideal body image should look like. They place too much importance on their weight and its role in their well being. They usually overestimate their body size. Cooper and Taylor (1988, see A2 Level Psychology page 216) reported an overestimation in patients with bulimia. People with eating disorder also have a desired body size that is smaller than it is for healthy women. Bulimics perceive their body size to be larger than do control individuals of the same size, and they also mistakenly believe that eating a small snack has a noticeable effect on their body size (McKenzie, Williamson, & Cubic, 1993, see A2 Level Psychology page 216). Eating disorders are characterised by obsessive thinking about food and weight gain. Recent research has also linked the disorder to perfectionism, which involves the individual having impossibly high standards for themselves. Individuals high in perfectionism may strive to achieve an unrealistically slim body shape. The mothers of girls with disordered eating often have perfectionist tendencies (Pike & Rodin, 1991, see A2 Level Psychology page 216). EVALUATION OF COGNITIVE EXPLANATIONS Scientific evidence. The research evidence on cognitive factors is scientific as it is based on the experimental method. For example, the research on body size distortion has been tested experimentally because eating disorder patients are compared against control groups and their body image distortion is measurable. This means the research has scientific validity. Cognitive dysfunction—cause or consequence? The cognitive explanations can only explain eating disorders so far, as they do not explain what caused the breakdown in information processing in the first place. Moreover, they may be an effect rather than a cause of the disorder, in which case they are a characteristic, rather than a causal factor. Cultural Explanations RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR CULTURAL EXPLANATIONS Social learning theory explains that eating disorders develop as a result of observation and imitation of role models. Such role models are seen as successful and so the observer experiences vicarious reinforcement (i.e. observes others experiencing rewards) and desires the same rewards for themselves so that they can experience direct reinforcement through operant conditioning. Evidence to support this is Barlow and Durand’s (1995, see A2 Level Psychology page 217) findings that more than half of Miss America contestants are 15% or more below their expected body weight, which of course is one of the diagnostic criteria for anorexia. Nasser (1986, see A2 Level Psychology page 217) compared Egyptian women studying in Cairo and London; none of those studying in Cairo developed eating disorders, but 12% of those studying in London did. This shows the influence of Western standards of idealised body images and that eating disorders are linked to cultural norms and role models. The fact that eating disorders are considerably more common in Western than Eastern cultures has led to them being classed as a culture-bound syndrome. For example, about one woman in 200 suffers from anorexia nervosa in Western Europe and the United States. In Hong Kong, in contrast, only one person out of more than 2000 Chinese people sampled had anorexia (Sing, 1994, see A2 Level Psychology page 217). RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST CULTURAL EXPALNATIONS Most of the distorted beliefs held by anorexic and bulimic patients are merely exaggerated versions of the beliefs held by society at large (Cooper, 1994, see A2 Level Psychology< pages 217–218). This means that the cultural explanation fails to clearly discriminate between those who go on to develop an eating disorder and those who do not, despite sharing similar concerns about weight and body size. EVALUATION OF CULTURAL EXPLANATIONS Cultural factors do not account for variations in vulnerability to eating disorder. The great majority of young women are exposed to cultural pressures towards slimness yet do not develop eating disorders, and so these factors lack explanatory power as they do not explain why some people are more influenced by these factors than others. Operant conditioning does not account for differences in the perception of reinforcement. This can of course account for why some find weight loss more rewarding than others. Operant conditioning does not account for such differences because it ignores cognitive factors, which are considered unscientific and not worthy of study as they are not observable or measurable. Yet cognitive factors seem to be a causal factor, given the cognitive distortions shown and the obsessive thinking many people with eating disorders display. Social learning theory accounts for cognition and appears to be valid (correct). Social learning theory is more sophisticated than the traditional learning theories because it accounts for cognition in its explanation that we can learn through vicarious reinforcement and imitation, as this involves expectations and thought about which role model should be imitated and what rewards can be expected. Moreover, it accounts for eating disorders as a cultural phenomenon, as role models and social learning differ across cultures. Research on cultural variations provides support for the validity of social learning theory, as do patients’ accounts of their susceptibility to the idealised body images shown in magazines. Deterministic. The behavioural explanations can be criticised as environmentally deterministic because they imply that the environment shapes behaviour, which ignores the free will of the individual to reject the influence of the environment. Reductionism. The behavioural explanations are also reductionist because they only consider nurture. They are too simplistic as they do not consider other explanations for eating disorders such as biological and cognitive factors. SO WHAT DOES THIS MEAN? The strength of the psychological explanations is that they cover a number of factors. However, any one of these explanations on their own is reductionist as they only consider one level of explanation. The strong evidence for a genetic basis shows that psychological factors alone cannot account for eating disorders and so a multi-dimensional approach is needed to fully account for eating disorders. The compromise position of the diathesis–stress model best accounts for the influence of nature (genes) and nurture (environment) and so is the most comprehensive account of anorexia or bulimia. This means an individual may inherit a vulnerability to disorder, (particular genes that cause biochemical and brain structural abnormality: the diathesis), which places the individual at greater risk of developing the disorder. But it is not inevitable that the disorder will develop because it depends on the interaction of the diathesis with psycho-social stressors. Thus, an interactionist and idiographic (individual) approach is needed, which means that the factors may interact in different ways to explain the development of the disorders in different individuals rather than there being one multi-factorial explanation that accounts for development in all anorexics and bulimics. Such a nomothetic approach, i.e. trying to provide a universal explanation, is oversimplified. OVER TO YOU 1. Outline and evaluate psychological explanations of one eating disorder. (25 marks) 2(a). Outline the clinical characteristics of one eating disorder. (5 marks) 2(b). Critically consider the psychological explanations of one eating disorder. (20 marks)