Nubia museum head links Boston, Egypt

advertisement

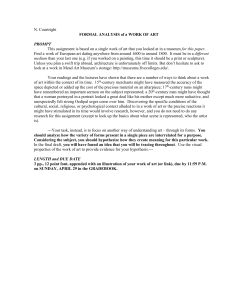

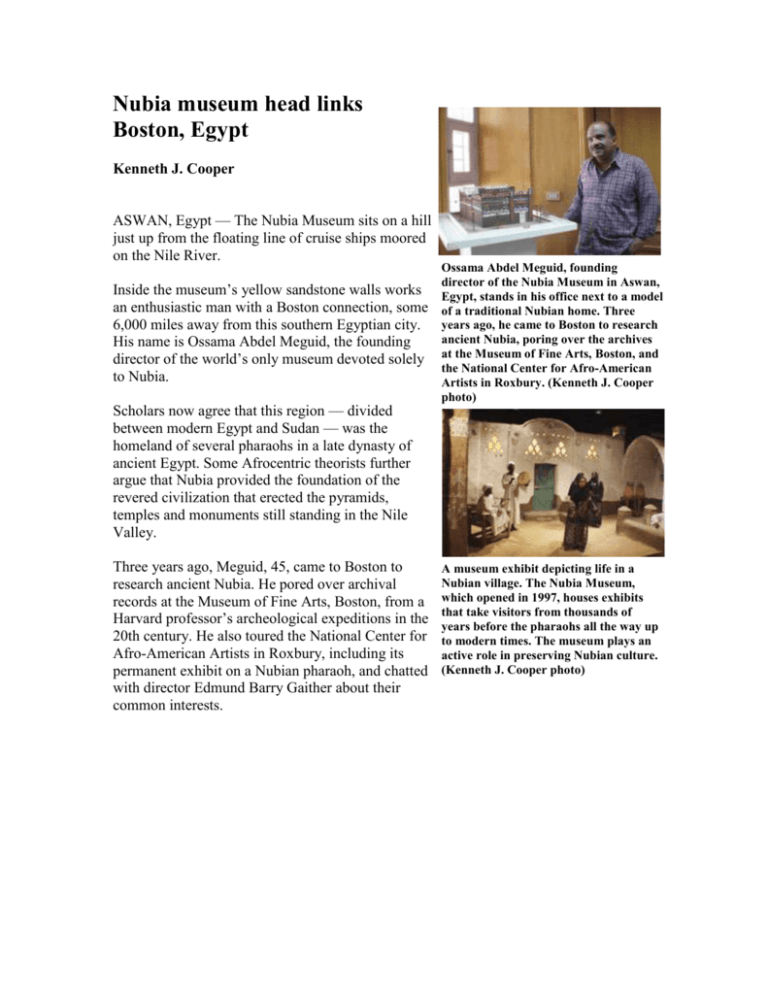

Nubia museum head links Boston, Egypt Kenneth J. Cooper ASWAN, Egypt — The Nubia Museum sits on a hill just up from the floating line of cruise ships moored on the Nile River. Inside the museum’s yellow sandstone walls works an enthusiastic man with a Boston connection, some 6,000 miles away from this southern Egyptian city. His name is Ossama Abdel Meguid, the founding director of the world’s only museum devoted solely to Nubia. Scholars now agree that this region — divided between modern Egypt and Sudan — was the homeland of several pharaohs in a late dynasty of ancient Egypt. Some Afrocentric theorists further argue that Nubia provided the foundation of the revered civilization that erected the pyramids, temples and monuments still standing in the Nile Valley. Three years ago, Meguid, 45, came to Boston to research ancient Nubia. He pored over archival records at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from a Harvard professor’s archeological expeditions in the 20th century. He also toured the National Center for Afro-American Artists in Roxbury, including its permanent exhibit on a Nubian pharaoh, and chatted with director Edmund Barry Gaither about their common interests. Ossama Abdel Meguid, founding director of the Nubia Museum in Aswan, Egypt, stands in his office next to a model of a traditional Nubian home. Three years ago, he came to Boston to research ancient Nubia, poring over the archives at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the National Center for Afro-American Artists in Roxbury. (Kenneth J. Cooper photo) A museum exhibit depicting life in a Nubian village. The Nubia Museum, which opened in 1997, houses exhibits that take visitors from thousands of years before the pharaohs all the way up to modern times. The museum plays an active role in preserving Nubian culture. (Kenneth J. Cooper photo) Meguid’s main mission as a Fulbright Scholar at the MFA for five months in 2005 and 2006 was to study the archives of George Reisner, a Harvard professor who conducted the first archeological survey of Nubia in 1907 and 1908 then spent four decades conducting digs in the main Nubian sites. “The Museum of Fine Arts has the best archive of Nubian archeology,” Meguid said during a recentinterview in his office. He paused, then added immodestly: “After us.” Usually, the international exchange program sponsored by the State Department places Fulbright Scholars like Meguid at universities. The Museum of Fine Arts welcomed the rare presence of one. “We wouldn’t normally have accepted a Fulbright Scholar because we’re not a university. [But] I knew Ossama. I knew how serious a scholar he would be,” explained Rita Freed, the John F. Cogan, Jr. and Mary L. Cornell Chair of Art of the Ancient World at the MFA. “He was an absolute delight to have,” she continued. “He instantly became one of the museum family.” The archives that Meguid researched, Freed said, include Reisner’s diaries, maps and photographs of ancient tombs in more than 1,000 cemeteries he excavated south of the Nile’s first cataract, or rapids, which lies just below Aswan. “This is the only place he could consult those materials, and we have the objects [Reisner found], thanks to a division with the Egyptian Museum” in Cairo, she said. “We have the finest collection of Nubian artifacts outside of Sudan … There are only a few places in the world you can see Nubian art, period.” While at the MFA, Meguid gave a lecture about the Nubia Museum and contemporary Nubian culture. He did so wearing traditional robe called a gallabiya and a turban, Freed said. The Nubia Museum, which opened in 1997 with funding from the government of Egypt and technical assistance from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, houses exhibits that take visitors from thousands of years before the pharaohs to modern times. On display, for instance, are ancient statues of Nubian pharaohs Taharka, Shabaka and Aspelta. On its landscaped grounds are outdoor exhibits, unusual for a museum. One is a mock cave whose walls are embedded with pre-historic rock carvings and paintings of African wildlife. There is also a traditional Nubian house, with images painted on outside walls built from mud with a technique that may have given adobe construction its name. The museum plays an active role in preserving Nubian culture. The part of ancient Nubia that is across the border in northern Sudan still exists, but little of the other part that was in southern Egypt does. It was submerged when the Aswan High Dam was completed south of the city in 1964, forcing the relocation of 50,000 Nubians and severing a people from their ancient homeland. The prehistoric images in rock found in the outdoor cave were rescued before the waters of Lake Nasser, the world’s largest artificial lake, inundated Nubia. Besides documenting the known history of Nubia, Meguid said other purposes of the museum are to show that the ancient land is submerged and that “Nubians sacrificed their homeland … for the rest of Egypt.” Freed said the museum “does a lot to keep the old Nubian customs, Nubian language and Nubian identity alive … so that Nubia remains a living tradition, not something that lives in the memories of grandparents.” The museum hosts Nubian performances, for example. “We are a community museum, and we interact with the community,” Meguid said. Community service was one of the topics that Gaither said he had discussed with Meguid at the National Center for Afro-American Artists. “I felt that we both believed in museums as living expressions of community—supporting cultural and artistic production, studying and preserving those traditions, passing them along to the younger generation, and where appropriate, helping people earn a living,” Gaither said in an e-mail. A replica of the burial chamber of Nubian pharaoh Aspelta is at the Roxbury museum, a permanent exhibit that Meguid recalled from his visit. That exhibit not only links Nubia and Boston, and Meguid and Gaither, but also bestows the National Center with a distinction of its own. “Sometimes people ask why we undertook such a project — no other American black museums have,” Gaither said. “And we reply that if we want to say to young black people that they descend from kings and queens, their logical reply might be, ‘Show me the evidence.’ Museums are in the business of providing historical evidence of civilizations.”