Global Citizenship Essay

advertisement

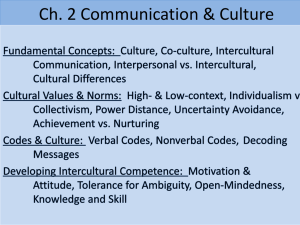

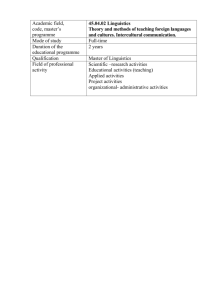

Adam Guss 11/28/13 Global Citizenship Essay Developing Cultural Adaptability To be an effective communicator in today’s globalized community, one has to understand that not everybody comes from the same background of values, beliefs, rituals, and the like as you do and thus do things differently. While this is by all means a true statement, it is only a small part of what the term “global citizenship” means. To be a global citizen, one not only has to understand other cultures, but also the impact your own culture has on perceptions of other ones. This implies deep understanding of one’s own culture in order to have something to compare other cultures to. Global citizenship is like the lens of a telescope: it helps one to see very interesting objects that are much different from what we know on Earth but it also distorts those objects. In order to understand those objects more fully, one has to know exactly what the specifications of the lens are. The trouble with global citizenship is that it is sometimes hard to see the exact relationship between the lens (one’s own culture) and the distant objects (other cultures). However, once seen, those distant objects can be very important to understanding more of our universe. Many different people have tried to define global citizenship. One of the best working definitions is that although global citizenship means something different to each person, in general, global citizenship is varying degrees of ability to interact with people from other cultures. This is what has been proposed by Milton Bennett. He says that “there… seemed to be six distinct kinds of experience spread across the continuum from ethnocentrism and ethnorelativism.” (Bennett 1) He defined each of these as (from the most ethnocentric view of other cultures to the most ethnorelativistic view) denial, defense, minimization, acceptance, adaptation, and integration. In class, we took a survey (the Intercultural Development Inventory or IDI) to determine where each of us were on this spectrum of ethnocentrism to ethnorelativism. On the whole, our class was right around minimization (the middle of the spectrum) but believed ourselves to be well into acceptance. This was an “orientation gap” of about 27 points. According to the IDI, a gap of seven points is significant. This is therefore a significant shift in our perceptions of ourselves and our actual intercultural skills. This adds an effect to the definition as well: there are degrees of ability to communicate across cultures but there are differences between how we think we communicate and how others (perhaps from the other cultures) perceive our communication. What I think this means for Honors students is that we want to live up to our calling as interculturally competent Honors students but are still just starting. One thing is for certain, it seems as if we are all interested in further developing our intercultural skills. One of the most important things that I noticed in most of the readings was how important it was for people to become interculturally competent enough to call themselves “global citizens”. So why is being a global citizen important in every day life? Sangeeta Gupta answered this question by writing “the development of a global mindset, cultural competency, and cultural adaptability are critical foundational skills that every leader needs to possess to maximize his or her own impact and productivity as well as that of the team.” (Gupta 157) In essence, if one wished to become successful in his or her field, being competent in communicating across cultures is paramount. Gupta also mentions how certain cultures stress relationships, time commitment, formality, and nonverbal communication at different degrees than other cultures. It is often difficult to develop the ability to see past one’s own culture’s values after many years though. If it is engrained into an adult to think that everybody should be on time, no matter what the situation, they often come off as appearing insensitive to people of other cultures. Fernando Reimers suggests that “schools and universities around the world are not adequately preparing ordinary citizens to understand the nature of global challenges.” (Reimers 24) To overcome such challenges, Reimers writes that global competency needs to be developed in students and children as soon as possible. He breaks down the development of this global competency into three dimensions of educational opportunities: the development of attitudes, values, and skills that reflect openness, interest, and positive disposition towards diverse cultures, the study of foreign languages, and the acquiring of academic knowledge in comparative fields and the ability to integrate crossdisciplinary materials when solving questions about globalization. If teachers and professors manage to integrate these sorts of opportunities into their curriculum, children will not only understand the nature of our globalized world at a younger age but will also be able to overcome challenges that spring up as a result of this modern world when the opportunity presents itself. If children are exposed to these opportunities at a young age, they will be set up for success in the globalized work force when they come of age. Being a part of the Honors program is going to be one of the most useful tool for developing my own global citizenship. I already feel like I have developed my intercultural competency more than I have in nearly nineteen years. During the summer, while reading about Deogratias’ flight from Burundi and his subsequent adaptation to the American style of living, I got my first taste of what it means to understand the plight of someone from a different culture. During discussions in and outside of class, this understanding was furthered by the acknowledgement of similar issues right in my own backyard. Many Somalian refugees come to Mankato and go to the same high school I went to and I never paid them a second thought. What I learned most from Strength in What Remains is that every person has a story and many of them are just looking for someone to help them to tell it. I hope I can have more experiences like the ones I participated in related to this book over the next four years to develop my intercultural skills further. While it is hard to define global citizenship or put a set level on the intercultural capabilities of a person, I think that it is safe to say that most people (including myself) want to further their understanding of other cultures. Some may want to do so for career reasons, some for academic reasons, and some to communicate effectively with family or friends. There are many paths one can take to develop this competency and all of them are just as effective as the effort put into them. The importance of developing global citizenship and intercultural competency though is worth every effort put into doing so as it will help a person become more successful in their job, more caring and empathetic towards people from other cultures, and better, more caring citizens overall. To bring this discussion back to the analogy of the telescope: while it may take some work to develop the lens of the telescope and then do the calculations required to understand those distant objects, it is important and necessary to do so for the sake of understanding the universe. Bibliography 1. Bennett, M. J. “Becoming Interculturally Competent.” Toward multiculturalism: A reader in multicultural education. 8 Jan. 2004. Web. 12 Nov. 2013. 2. Gupta, S. R. “Beyond Borders: Leading in Today’s Multicultural World.” Contemporary Leadership and Intercultural Competence: Exploring the Cross-Cultural Dynamics within Organizations. 2009. Web. 4 Nov. 2013. 3. Reimers, F. M. “Global Competency: Educating the World.” Harvard International Review. Winter 2009. Web. 4 Nov. 2013. 4. Kidder, Tracy. Strength in What Remains. New York: Random House, 2009. Print.