Reducing the Regulation of Stock Food and Pet Food RIS

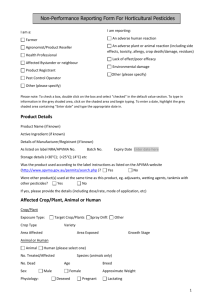

advertisement