inward augmentation

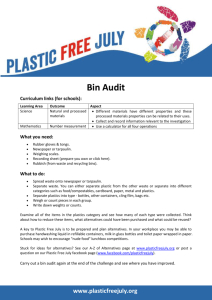

advertisement