Lesson Plan (Aztec) - Art History Teaching Resources

advertisement

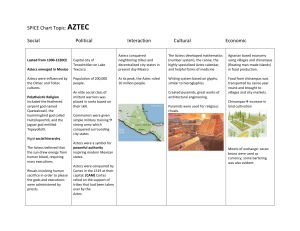

Aztec Art of Meso America In Aztec art, we face some of the same issues and ideas as we did in Africa, namely that there is a rich existing culture for us to examine, and also the effects of Europeans invaders (this time the Spanish conquistadors). KEYWORDS: Aztec (middle Am): The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology. - Aztecs were the last of the great native Mesoamerican civilizations - the term was applied to them in 19th century, previously describing dominant people of the central Mexico, they saw themselves as the Mexica - Tenochtitlan – the capital of Aztecs – is a nowadays Mexico City - the city was founded in 1345 on the island of the lake Texcoco; from there Aztecs began their expansion and consolidation of the empire - Motecuhzoma II was the last independent ruler of the empire (island counted over 200 000 people) - Spanish under Hernando Cortes entered the city by November 1519. By 1521 the Spanish took over the city. - Many artworks and structures were destroyed in search for gold → almost non golden and silver Aztec object survive as all the found ones were melted down Mesoamerica: Mesoamerica is a region and culture area in the Americas, extending approximately from central Mexico to Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, within which a number of pre-Columbian societies flourished before the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. Basically – CENTRAL AMERICA. Indigenous: the original peoples of a region; “Pre-Columbian” = The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents (we’re just looking at this period post-1333, so the time immediately before Columbus’ discovery & invasion precipitated multiple invasions). AZTEC EMPIRE SLIDE: MAP OF AZTEC EMPIRE The greatness and power achieved by the Aztec empire occurred in the Late Postclassic period, the final stage of ancient Mexico that spanned the 13th to the early 16th centuries. This era had its counterpart in 15th-century Europe in the intellectual movement in the sciences and the arts known as the Renaissance. The Aztecs ended up imposing their political ideals and dominance on longtime allies and other neighboring peoples, founding an imposing empire in the process. In 1325 the Aztecs founded their capital, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, in central Mesoamerica, a geographic area featuring lakes and mountains. This was the 1 political, religious, and cultural center of the Aztec empire. From this city, it extended its supremacy over an immense territory. SLIDE: The Founding of Tenochtitlan, Page from Codex Mendoza. Aztec, 1545. Ink and color on paper. This is the first page of the Codex Mendoza. The Codex Mendoza is an Aztec codex, created about twenty years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico with the intent that it be seen by Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. It contains a history of the Aztec rulers and their conquests, a list of the tribute paid by the conquered, and a description of daily Aztec life, in traditional Aztec pictograms with Spanish explanations and commentary. The codex is named after Antonio de Mendoza, then the viceroy of New Spain, who may have commissioned it. It shows the capital city of Tenochtitlan divided into four quadrants, with the leaders of the city housed in each quadrant. Drawn by an Aztec scribe for a Spanish viceroy Eagle in a cactus, the place symbol for Tenochtitlan is in the center: founding legend said that the city should be built on the place where a cactus grows out of a stone with an eagle inside it The city was divided by water into 4 sections The central quadrangular space housed the most important ritual buildings. First among them was the Templo Mayor, the double pyramid dedicated to the worship of Huitzilopochtli (Who-wheat – zillo – pocktli) the patron of war, and Tlaloc, the god of rain. The ritual architectural complex was expanded whenever an Aztec governor ascended to the throne, so that by the end of the 15th century, the fame of its monumentality and greatness had spread throughout Mesoamerica. Mesoamerican maps and some European had East at the top top section (East) has a house – reference to the great twin pyramid house is set in opposition to the skull rack which was also a prominent feature in the ritual precinct the sacrificial victims climbed the tall stairs to the temple, where priests threw them on stones and quickly pulled their beating hearts – this was supposed to assure survival of the sun; then the body was rolled down the stairs and dismembered at the bottom : the skull rack was formed of the skulls of these victims 51 year names run as a border around the page SLIDE: AZTEC CALENDAR The Aztecs used glyphs, or pictographs, to record history, geographic environments, and mythic tales. The range of surfaces on which glyphs were written included stone, ceramics, and textiles, as well as books, known as codices, mainly drafted on agave- 2 fiber paper and deerskin. The tlacuilos or painter-scribes drew the essential signs that indicated the basic elements of the story, and supplementary information was learned by heart. The numbering system was based on groups of 20, with a method of circles or dots that each had the value of one. There were two parallel calendars in Mesoamerica. One was a solar, agricultural calendar of 360 working days, to which were added five unlucky days called nemontemi. The tonalamatl was the divinatory 260-day ritual calendar, handled by the priests. Every 52 years, the two cycles began on the same day, marking the equivalent of the turn of one of our centuries. To celebrate this event, the Aztecs burned two bundles of reeds, xiuhmopilli, symbolizing the dead years, and lit a new fire that would burn for 52 more years. * Slide: the great Calendar Stone, Aztec, ca. 1500, 12 feet across 24 tons - it was saved from being recycled as building material late in the 18th century - despite the name it does not function as any sort of useful calendar but works rather as a record of calendrical cataclysm - it represents an expanded cosmic scheme - basic representation is of solar diadem, encircled with fire serpents and framing the 20 day names - the serpents have stylized flames on their backs, their faces meet at the bottom - at the center is the outline of the day sign, Ollin, or Movement, within which are described 4 dates - 4 dates commemorate the 4 Suns, or previous eras, known by the day names on which their destruction took place - On Four Wind, upper left, np. the world and its inhabitants were destroyed by great winds - others are 4 Jaguar, 4 Rain, and 4 Water - according to the Aztecs, the current world would end in cataclysm on Four Movement (earthquake) - the band, round disk with triangular projects denoting rays, is the symbol of Sun - at the very center is the frontal face of a female earth monster, bordered by clawed extremities that grasp human hearts - thus the stone represents the Sun fallen on Earth → the complete cataclysm - it was probably set on the ground and anointed with sacrificial blood to keep away the apocalypse SLIDE: Feather headdress Aztec society was made up of two completely differentiated social classes: the pipiltin, or nobility, and the macehualtin, or commoners. The nobility were allowed to accumulate and display wealth, including precious objects— especially jade, feathers, and fur—and elegant clothing made of cotton. They lived in palatial buildings, practiced polygamy, held public office, were exempt from manual labor, and received tributary payment. Commoners were the bulk of the population and were responsible for all heavy labor such as agriculture and transport. They lived in simple huts, dressed in rough clothing 3 made of ixtle fiber, were required to be monogamous, and were prohibited, on pain of death, from accumulating, much less exhibiting, wealth. Artisans and merchants were also commoners, but the state exempted them from farm work. In exchange, they had to pay as tribute the objects they produced with their hands or those they brought from far-off territories. SLIDE: Aztec gold jewelry The search for gold had brought Christopher Columbus, albeit mistakenly, to the coast of America in 1492, having miscalculated the circumference of the globe by about 25 percent. Columbus, a master mariner then in the service of Spain, and an avid reader, was searching for Japan, the island of "endless gold," about which he had read with great excitement in Marco Polo's Travels. Convinced that fabled island of endless gold was not far from the small island on which he had landed, Columbus went ashore and, unfurling royal standards, claimed it for his sponsors, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain—thereby initiating what would become the vast Spanish empire in America. In 1519, Hernán Cortés and a band of European adventurers disembarked on the coast of Mexico, similarly excited by the promise of gold, thus beginning the conquest of the Aztec empire. This process culminated in the bloody taking of Mexico-Tenochtitlan on August 13, 1521, and the defeat of Motecuhzoma II. The Aztec king Motecuhzoma (Montezuma II), whose capital city was Tenochtitlan, in the central highlands. Wishing to prevent the arrival of the Spaniards in his city, he sent emissaries to Cortés with extravagant gifts: a gold disk the size of a cartwheel; a silver disk of the same size; diadems, earrings, and figures of gold and mosaic; armbands of silver; multistrand necklaces with hundreds of gold beads and red and green stone; hollow gold ornaments cast in complex shapes; shields and helmets covered in turquoise mosaic; brilliant feather fans and headpieces; elaborate garments and costumes—all were among the exotic and wonderfully strange objects the Spaniards received as tribute. Cortés sent the gifts to Spain, and in the spring of 1520 the treasure was presented to the newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, king of Spain. Great excitement greeted the wondrous objects and learned men commented upon them. No opinion is better known or valued than that of Albrecht Dürer, who saw the treasure in Brussels in August 1521. In the diary of his journey to the Netherlands (1520–21), he wrote of the gifts "brought to the King from the new golden land: a whole golden sun, a whole yard wide, likewise a whole silver moon, also equally big, likewise two chambers full of … wonderful things for various uses, that are much more beautiful to behold than things of which miracles are made." Unfortunately, such learned interest and appreciation were of modest duration, and none of the works from this hoard is known to have survived. The cartwheels of gold and silver and all the pieces of precious metal were melted down, and objects of more ephemeral materials discarded. Only a few pieces of jewelry survived, a small reminder of the glory and fame of ancient Mexico. * Slide: Feather Headdress of Moctezuma, Aztec, before 1519 4 - feather headdress thought to be given by Motecuhzoma to Cortes, shipped to emperor Charles V of Spain - extremely fragile and very few featherworks survive - extremely precious: the iridescent feathers in this headdress are taken from a rare quetzal bird, of which the adult male has only two in his tail - the feathers were gathered into bunches and sewn to the frame - featherworkers were estimed craftsmen at the court 1. Sculpture of Huastec Goddess, stone statue, Mexico 900-1521 AD - - - - A statue of a woman, from what is now northern Mexico, but which around 1400, was the land of the Huastec people. We now know about the Aztecs, and how the great Aztec Empire was conquered by the Spaniards in the 1520s. We hear much less about the people that the Aztecs themselves had conquered to build their empire. One of the most interesting people subjugated by the Aztecs were their northern neighbours, the Huastecs. We know that the Huastecs lived on Mexico's northern Gulf coast, in the area around modern Veracruz (Olmec), and that between the tenth and the fifteenth centuries they had a flourishing city culture. But around 1400, this prosperous world was overwhelmed by the aggressive Aztec state in the south, and the Huastec ruling class was effectively liquidated. There's very little now that would enable us to reconstruct the world and the ideas of the Huastecs. There is no trace of any writing, and all we have to go on is Aztec accounts of the people they conquered, as transmitted through the Spanish after they in their turn had liquidated the Aztecs. So if we want the Huastec to speak to us directly, we have to go to the objects they left behind. These are their only documents, and among the most eloquent of them are groups of highly distinctive stone statues. Statue is about five feet (1.5m) high, so more-or-less life-size, but she's not at all lifelike. Carved out of a very thin piece of sandstone, less than six inches (15 cm) thick. She's really just a series of geometric shapes. Her small head is unexpectedly animated, she appears to be looking up and to the side towards something, and her lips are open, as though she may even be speaking. She may be a mother goddess. We know virtually nothing about the Huastec mother goddess, but we do know that for the conquering Aztecs she was the same being as their own mother goddess, Tlazolteotl (Tee-lazo-teo-tl). Tlazolteotl literally means, in the Aztec language, 'filth goddess' - transforming organic waste and excrement into healthy new life, guaranteeing the great cycle of natural regeneration (children are born, this is a messy business). Another of her names is 'eater of filth' - she consumes dirt and purifies it. So, if we can read our goddess in the same light as the Aztecs, that's perhaps, disconcertingly, why her mouth is open and her eyes are rolling upwards. 5 Her most striking feature is a huge, fan-shaped head-dress. It's about ten times the size of her head, and although part of it's broken off, you can see that, like the rest of her, it's conceived as an assemblage of geometric shapes. A head-dress like this must have been a totally unambiguous statement of who this figure was. Maddeningly, it's a statement that we cannot read now with any confidence but it is certainly a symbol of status. 2. Double-Headed Serpent, mosaic figurine, Mexico 1400-1600 AD In the course of the Spanish Conquest, Aztec culture was almost completely obliterated. Virtually all the accounts of the Aztec Empire were written by the Spaniards who overthrew it, and so they have to be read with considerable scepticism. It's all the more important, then, to be able to examine what we can consider as the unadulterated Aztec sources, the things made by them that have survived. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Aztecs had of course no idea that they were on the brink of destruction. The serpent is made up of about two thousand tiny pieces of turquoise, set on to a curved wooden frame, about a foot and a half (45 cm) wide. The snake's in profile. It's got one body, shared by two heads, and the body curls up and down in a 'W' shape, to finish at each end in a savage, snarling, head. The body of the snake's entirely in turquoise, but when you come to the snouts and the gums, a brilliant red shell has been used, and then the teeth are picked out in white shell, culminating in huge, terrifying fangs. The bright red shell used on the mouth and the nose is from the 'Spondylus princeps', the thorny oyster, which was a really highly prized shell in ancient Mexico because of this fabulous scarlet red colour, and also because it involved diving to great depths dangerous deep-sea diving - to harvest it as well. Scientists have established that turquoise in Aztec Mexico was transported over huge distances. Some pieces were mined over a thousand miles (1,600 km) from the capital, Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City. Goods like turquoise, shells, and resin, were traded across the whole of Central America, but it's more likely that the components of our serpent were forcibly exacted as tribute - compulsory levies from the peoples whom the Aztecs had conquered. This empire had been created only in the 1430s, less than a century before the Spaniards arrived, and it was maintained by aggressive military power, and tribute of gold, slaves and turquoise, sent regularly - and reluctantly - to Tenochtitlan by the subject provinces. The wealth generated by this trade and tribute allowed the Aztecs to build roads and causeways, canals and aqueducts, as well as major cities - urban landscapes that astonished the Spaniards as they marched in amazement through the Empire: Turquoise was also a key element royal regalia of the Aztec rulers The two-headed serpent was almost certainly worn or carried in a religious ceremony 6 The snake was important for the Aztecs as a symbolism of regeneration and resurrection. The tiny, carefully-angled, turquoise pieces are not far off the colour of the bluegreen tail-feathers of the quetzal bird, and they've been cut and bevelled to shimmer and flash just like the quetzal's iridescent feathers. This double-headed serpent may in fact be a representation of the god Quetzalcoatl who had these feathers Thesis Handout 7