Notes on how to answer the questions

advertisement

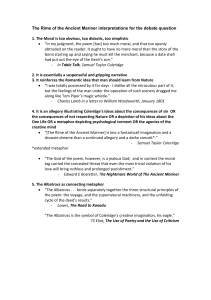

How to Answer the Questions in the Aspects of Narrative Exam (Unit 1, AS Level) Answering Section A the uneven question The questions in this section have a very specific focus. They are about how stories are told and they require candidates to write about the methods authors use in their storytelling. The best answers are produced by candidates who write confidently about the method in relation to the overarching story. This means briefly summarising the story and the discussing authorial methods in the light of it. The wording of the question helps you with this. For instance: Write about the ways Hosseini tells the story in Chapter 2. The following example shows how this can be done in a succinct way: Hosseini uses a retrospective, intradiagetic narrator, Amir, to tell the story within Chapter 2. Following on from the enigmatic, foreshadowing Chapter 1, this chapter is the first time we hear of Amir and Hassan’s childhood, showing us that the handling of time here has been taken back many years from June 2001. Amir tells us in the first personof their friendship, using imagery of nature and childhood to create a melancholic tone: “We would sit across from each other on a pair of high branches, naked feet dangling.” This reflects the innocence of the pair, free from the worldly conflicts that surrounded them. The following, shows how it should not been done: Hosseini uses lots of alliteration and personification to tell the story in Chapter 2. TOP TIPS You don’t get marks for throwing in a literary term, only for if you use it correctly and explain what its effect is. Everything you write about MUST connect to how the story is told. Focus on the larger features of narrative, such as voice or structure, rather than discussing the effect of individual words. If you are writing about an extract (part of a larger story) you must be able to say how the extract fits into the larger story and to write about the significance of its placement in the story as a whole. If a named form is being used, refer to it explicitly in your opening: “Auden’s ballad, Miss Gee . . .”. This takes you no time at all and immediately gains you a mark. Once you’ve established the story and form/genre you need to explore how the story is told/the narrative or poetic methods at work. You could approach the question chronologically or by point/aspect of narrative. But, whichever way you choose, you must closely examine how the story has been constructed and the effects of the writer’s choice of authorial methods. REVISION TIP For each poem/section and a selection of chapters from the novels, try writing a short opening paragraph identifying what the story is. Reference form/genre within this opening. Bullet point a valid approach for the whole essay. Practise writing several of these essays in timed conditions. Exemplar Mariner essay (Bd 6) Write about the ways Coleridge tells the story in Part 6 of The Rime of the Ancient In part 6 of „The Rime of the Ancient Mariner‟, the Mariner is being returned to his “own countrée” but as explained at the end of part 5, must still do penance. Thus, the two voices talking above his head drive him towards the shore but he is faced by the corpses of his shipmates once more. Clearly, then, both setting and characterisation are of the utmost importance, and they are used by Coleridge to show the two sides to this poem: the fantastic spiritual aspect, as embodied by the voices and the inhabited crew; and the element of security and normality that comes with his return to land. The initial setting is a strange one, with air that is “cut away before,/And closes from behind”, with the strange weather emphasised because it its told of by the disembodied voices. Throughout this section of the poem, it is night and Coleridge makes much of the inner symbolism, where by the gentleness of the moon is used as a contrast to the earlier fierce sun to show the varying natures of the Christian God which plays such a large part in this poem. Being set at night, the scene is „illuminated‟ by the moon light, and as “on the day the moon light lay” the Mariner starts to find the safety of his homeland once more. From the initial strange weather “breath‟d a wind” that carries the Mariner back, and, this is in sharp contrast to the earlier stillness of the “silent sea”, to such an extent that it is described as blowing “sweetly, sweetly” (with the repetition used to show the child-like unadulterated pleasure this simple act gives the Mariner). He returns to his safe “Harbour-bay”, described variously as “clear as glass” “white all o’er” and “white with silent light” to show the safety, purity and holiness of the land after his hellish voyage, and to the guidance of his “light-house top…Hill…[and] Kirk”, that is a repetition of an earlier description to remind is of the circular nature of the poem, and indeed his sea voyage. Coleridge uses setting, particularly with the colour and symbolism of the Moon, to show the sharp contrast between the blessed land and the dangerous sea. As a narrative about a journey, it is only to be expected that setting plays such a major role. But part 6 is also significant because, in his return to land, the Mariner also returns to humanity. While the somewhat omniscient (hearing voices despite being unconscious) interdigetic narrator of the Mariner does not change, new voices are introduced: while they are not human, as indicated by “fly, brother, fly”, they do provide him with some company; which is more that can be said for the company of “dead men”, who terrify the Mariner so that he is “like one, that…doth walk in fear and dread” and then advance on him with flaming “stiff right arms” as if to attack him. Yet his redemption continues: the disembodied voices help him towards the land; the corpses may seem wicked, but “the spell was snapt” – itself showing a return to normality; the spirits leave the corpses and are revealed to be a “seraph-band” that shows his new closer connection with God; and, importantly, he is brought into contact with the Trinity (doubtlessly a religious link) of “Pilot, Pilot’s boy” and “Hermit good”. The characters are used to help the Mariner as he returns to his normal life, with the disembodiment of the Voices and disappearance of the “seraph-band” bringing the fantasy elements to an end. This part is linked back to other parts through the final reference to “the Albatross’s blood”, and this circular linking is a key part of the structure. The short rhyming stanzas, in iambic quatrameter, and the use of archaic language are equally important for maintaining this as a “lyrical ballad” (with the emphasis being on the ballad aspect). By thusly using the same style and structure as all other parts – even down to the predominant AB AB rhyme scheme – Coleridge pulls this together into a single coherent piece, which is necessary for the full story to be told and, equally understood. Answering Section A the even question Remember this question always sets up some sort of debate which you are expected to engage with. It asks you to consider multiple interpretations a text might afford and asks you to explore and evaluate these. It wants you to explore the relevance of contextual factors in finding meanings or exploring possible interpretations of a text. Alternative interpretations can be: the differing ways you as an individual choose to find meanings in a text; the way others in the class have interpreted a text; the way critics or other writers have interpreted the text (go down to the library and look at past copies of The English Review, read the critical information I have given you); consider how a feminist or a Marxist might interpret a text. You don’t need to refer explicitly to critics, but you must show that you recognise that there can be a range of interpretations of any given text and that these are worthy of evaluation. Phrases that help ensure that you are considering and evaluation different interpretations are: Some people argue . . . It has been argued . . . An interpretation that can be considered is . . . Whilst it is possible to argue that . . . Many have commented that . . . Although it is generally thought that . . . It could be said that . . . Perhaps . . . Contextual factors can be: The significance of the extract to the text as a whole Literary context (Auden: his interest in psychology; “Pylon poet”; World War II. Fitzgerald: the American Dream; Romantic realism; 1920s and prohibition. Coleridge: Industrial Revolution; Romanticism. Hosseini: the war in Afghanistan; American immigration.) This is not an exhaustive list and there is no point in adding bolt-on context to your writing. Flexible thinkers, however, will notice how a question lends itself to comment on particular factors. Any valid approach which engages fully with the debate set up in the question and which supports your viewpoint with well-selected and integrated textual reference will be rewarded. TOP TIPS Do not throw in context for the sake of it or if it does not illuminate the text in any way. There is no point in writing about Auden’s homosexuality or Coleridge’s drug habit if it has no relevance. The most important feature of this question is to have a good, strong, sustained argument. When answering the question, it is perfectly acceptable to consider the other side of the argument too. For instance, if answering a question on whether Auden’s poetry is obscure you might want to comment on Auden’s intellectual, political references; the anonymity of the voices in some of his poems; and then balance this discussion with a focus on the simplicity of a poem like “Miss Gee”. This question will often be connected in some way to Section A uneven question. For instance Part 4 of the Ancient Mariner contains the moment when he blesses the watersnakes and the even question asks whether the poem is about the power of prayer. REVISION TIP: For each Section A even question, annotate the question carefully; be certain that you have understood the debate/question being posed. Think carefully about how to present your arguments: you will need several wellsupported points explored in depth and detail with a sharp focus on the task at all times. Brainstorm a plan for each A2 question you have. Practise writing several questions in timed conditions. Exemplar Answer (Bd 6) How do you respond to the view that „The Rime of the Ancient Mariner‟ is “so mystifying, it simply befuddles and confuses the reader”? While the “Rime” is undoubtedly “mystifying”, I do not believe that this is necessarily a befuddling, confusing weakness. Although Coleridge’s contemporaries, notably Wordsworth, complained that the archaic language was a barrier when it came to giving poetry to the masses (as was the aim of Romanticism), modern readers are often used to the equally difficult and archaic Shakespearian syntax and indeed expect difficulty from even an 18th century poem such as this. Moreover, the mystifying aspects often make the “Rime” more open to alternative interpretations, and this allow each reader to have their own take on this poem. The most confusing aspect is the archaic language, although even this can be circumnavigated through the use of explanatory footnotes. However, such archaisms as “I looked upon the eldritch deck” (1798, line 244) create a deeper sense of spirituality, mysticism and the gothic movement that this text is also very close to. It is also important to note that this poem is largely about the journeying process of maturing: the Mariner leaves the safety of his homeland, presumably not as ancient as he is by the moment of telling the story, and in youthful ignorance shoots the Albatross and in developing comes to atone for this. For this reason, the confusion that comes from deciphering this text ensures that readers are also taken on a journey to maturity. The process of reading this text must be strenuous in the same way that the Mariner’s journey and the wedding-guest’s unwilling entrapment are also strenuous; the explicit moral at the close of the book shows how much Coleridge intended this to be a process of maturity for the reader as well. Equally, the mystifying nature of the story and the possibility for many interpretations also aids the reader. Coleridge ensured that he was meticulous in his research, about travelling but also about the psychology of the unconscious mind, and so the predominant interpretation is well supported: the traumatic effect of survivor guilt, as described in the poem, and the way it can cause false recollection and hallucinations, is well documented. However, there are numerous other interpretations which can be made by selecting certain aspects: the dangers of the sea voyage itself, with “the silent sea”, “the very deeps [that] did rot” and the possibility for death at sea speaking out against the tradition of press-ganging men into joining the Navy; the sun and the Moon show the contrasting natures of God and allow this poem to be read as a journey towards spiritual enlightenment or as an exploration of Coleridge’s own religious beliefs (whereby God was tied closely with nature) ; and the use of the wedding to create a framed narrative, along with the clearly fantastic elements, enable readers and critics to explore the nature of story-telling and the benefits of listening to the wisdom of an older generation (and indeed the folk-wisdom which should have warned the Mariner not to shoot the Albatross). Because the poem contains so many different aspects it can confuse many readers, but equally, the rich nature of this poem which stems from its mystifying nature ensures that readers who make the effort to understand it are richly rewarded. Too often, this poem is dismissed as being the product of a drug-induced nightmare, which far too much emphasis placed Coleridge’s developing opinion addiction and falsely equating the author with the narrator. Although the Mariner may be insane, Coleridge was not, as his attention to detail proves. Thus, the mystifying nature of the poem was almost certainly intentional, and as such it is integral to our understanding of Coleridge’s poetic aims. Far from befuddling and confusing readers it, like the moonlight and the lighthouse guiding the Mariner to his “own countrée”, serves to enlighten them. Answering Section B Remember this question always asks you to write about an aspect of narrative across three texts. You will be expected to present a well-structured, coherent argument with integrated textual support which evaluates and interprets. You must not write about the text you have used for section A. You have a choice of two questions, so it is important to think very carefully about which question best suits your three texts. You need to spend some time thinking around the question and ensuring that you understand its implications, and that you are able to construct a convincing and detailed response to the text. You must have an overarching sense of the whole story for each text and these points will need to be supported by evidence from the text. Think of this question as requiring you to write three mini essays, you don’t need to compare because that is implicit in the question. The key word in the question is SIGNIFICANCE. For instance, if the question asks you to look at the significance of climaxes, then you need to identify the key climatic moments in the texts, see how they are built up and then comment on their significance. A climax is only a climax if it is prepared for. A climax is not the end of a text. It is important to engage with the meanings that arise from the climax. REVISION TIPS For each Section B question, annotate the question carefully; be certain you have understood the argument being suggested. Think carefully about how to present your response: you will need well supported points for each text explored in depth and detail with a sharp focus on the task at all times. Brainstorm a plan fro each Section B question you have. Practise writing several questions in timed conditions. Section B Exemplar essay (Bd 6) “In narratives, what we are not told is just as important as what we are told.” Write about the significance of the gaps or of the untold stories in the narratives of the three writers you have studied. (42 marks) It is true to say that for most narratives, the untold aspects are no less important than those mentioned explicitly. The context of writing and of reading are often essential to shape our understanding, and the deeper meanings and interpretations are often implied; in addition, the unreliability of a narrator may push as to a conclusion completely at odds with the stated message. This is most noticeable in „The Great Gatsby‟. We cannot rely on any characters for any great length of time, not least because of their questionable moral values (with extra-marital affairs and sexual promiscuity at the heart of the novel). Gatsby lies about his past, ridiculously claiming in chapter IV to have “lived like a young rajah in all the capitals of Europe”, and Nick explicitly states as a Narrator that the “very phrases were worn so threadbare that they evoked no image”, yet soon afterwards, Nick is made to believe him, an effect so preposterous that Fitzgerald couches it in mock poetic terms: “I saw him opening a chest of rubies to ease, with their crimsonlighted depths, the gnawings of his broken heart”. (It should be noted that Fitzgerald’s own interpretations was that his work was a mixture of poetry and prose, and so the mocking result may be unintentional; I do not find him to have been successful.) Yet, however we feel about Nick’s reliability, the story of Gatsby’s past remains sketchy – a gap – as it is not convincingly told. But rather than being a fault, this heightens the enigma that Gatsby is. A further gap, linked to Nick’s unreliability, occurs in chapter II, when Nick admits, “I have been drunk just twice in my life, and the second time was that afternoon”. This ensures a gap in his recollection, and some ambiguity over the ending of the chapter which has led some readers to draw the conclusion that Nick may be hiding his homosexuality, having found himself in Mr McKee’s bedroom: “he was sitting up between the sheets, clad in his underwear, with a great portfolio in his hands”. Like Gatsby’s hidden past, when he built up his fortune through bootlegging, this leads to the interpretation that Nick, like the rest of America, and particularly the East Coast, has become corrupt. (Such gaps help to dismantle the supposed American dream, showing how the way in which money is made comes from immorality and illegality but the gaps also show that love has its own darkness especially when we remember that homosexuality was regarded as immoral at the start of the twentieth century). There are numerous, other untold stories in „The Great Gatsby‟, some due to Nick’s hazy narration: a notable example is that of the eyes of Dr Eckleberg, which George Wilson takes for the eyes of God, despite the assurance of Michaelis that “That’s just an advertisement”. The advertisement seems to have its own story which is not told. It seems to represent the hollow nature of America: like the original settlers who imbued the “fresh, green breast of the new world” with “the last and greatest of all human dreams”. Like Gatsby with regards to Daisy and the “orgastic future” of the green light, Wilson also builds his dreams higher than they can go and fails to acknowledge the reality (killing the wrong person). Yet because Wilson’s story is told from Nick‟ s viewpoint, the reader is never certain what Wilson actually might have believed. Thus the gaps and untold stories in „The Great Gatsby‟ serve to demonstrate the falsity of wealth, class and status in America as well as that of love and of the American dream. A sharp contrast to this is found in „The Kite Runner‟. Here the gaps are about unimportant things: there is a gap of several years between chapters 9 and 10, after Hassan leaves Kabul and before Amir does; there are also several gaps coming later in the story to speed events along and to skip the normal, non-traumatic years spent in America. The effect of this is twofold. First, it shows that the story is about certain elements: Amir’s relationship with Hassan and with Baba are more important than his teenage years without Hassan or his mid-life years after Baba’s death, so these years are missed out. Secondly, it enables Hosseini to adjust the timing so that events within the narrative match up to the real events in Afghanistan: the close link between politics and private lives is very important in this book, with Assef joining the Taliban and so being in a position to seize Sohrab and be found by Amir on his return. The gaps of completely untold stories push the „told‟ stories along faster, ensuring that the pace in quick enough to maintain interest without losing any integrity. However, there is another type of untold story in „The Kite Runner‟: the stories which are hidden for some time but which characters later become aware of. When these stories come out, they increase and realise the feelings of guilt. For example, Soraya’s confession of her past is difficult for her, shown by halting phrases such as “there was a long pause at the other end” and “a silence followed”, but it is more difficult for Amir because he cannot tell his story yet. His feelings do not remain untold, as he provides first person narrative that fully shows his emotions: in this case, Hosseini switches between emotional, fragmented shorter sentences (“I envied her. Her secret was out spoken”.) and longer confessional sentences to show the range of emotions he feels. He is similarly shown to be emotionally vulnerable when he finally finds out the truth about Baba and Hassan: “all I could manage was to whisper “No No No” all over and over again”. The untold stories are here used as the driving force behind the integral theme of guilt and redemption, with the build up of emotions caused by hiding these stories serving to heighten the tragedy (and our emotive response to it). Tennyson uses narrative gaps in a different, but no less effective, way. In „the Lotos-eaters and the Choric song‟, because the narrator focuses on the drug induced state of the mariners, the potential sinister purposes of the „mild eyed melancholy lotus eaters‟ who bring „confusion worse than death‟ is untold. Thus Tennyson places criticism entirely at the hands of the mariners who reject their homes in favour of the pleasure of drugs, turns us against them. Their culpability is perhaps shown by the corruption on the initial Spenserian stanza (which continues for five stanzas until the choric song begins) and the lengthening of stanzas and lines which combine with the over-embellished description to demonstrate the way that the sailors languish in their drugged state: this lengthening turns the reader against the sailors, as it begins to irritate. This is as much due to the way it is told as to what is actually told to us: rather than being told, we are shown, and thus feel the effect more strongly. In another of his poems, „The Lady of Shalott‟, Tennyson only hints at the curse which “is on her if she stay/To look down on Camelot”. Although the narrator is omniscient he neither confirms or denies the existence of this curse, and it could be seen that the Lady’s tragic death comes about because she believes in the curse and thus takes no action to prevent her death (in as much as “her blood was frozen slowly because she took to the river” at the closing of the day). In the poem Tennyson criticises the way in which people, and particularly artists, often choose to ignore reality: the Lady of Shalott accepts her impotence, perhaps representing the behaviour of women at the time, and is ignorant of the coldness of the shallow Lancelot who is barely affected by her death. The untold story is the reality which she chooses to ignore, leading to her wasting her life.