Dubliners

advertisement

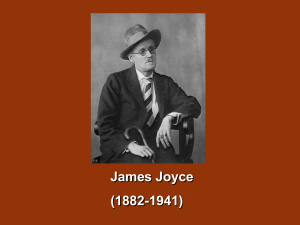

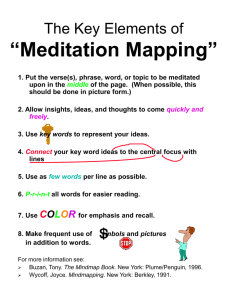

To what extent does Joyce privilege the visual over other narrative means in Dubliners? The correlation between the art of the painter and that of the novelist exists in the fact that both attempt to represent reality with an “uncompromising visual focus” (Doherty 49), as life is, after all, experienced through the eyes. Paying particular attention to Araby, The Dead, and Two Gallants, this paper will explore this focus on the “visual” by arguing that Joyce’s attention to descriptive detail (especially of the body) is not for the sake of realist embellishment but as a means of visual focalization and communication, to get across an image that will give the reader an accurate depiction of the picture Joyce aims to represent, an image that is as fixed and unmovable as that of a painting. As such, I maintain that Joyce privileges sight and the visual over other, more subjective, narrative means that “magnify an awareness of the self” (Olson 3) (such as epiphany etc., any technique to do with thought rather than the senses) because it represents reality and the ordinary in such a way that allows the reader to experience the novel through the eyes rather than through the mind of the narrator (as per a stream of consciousness). Whereas other modernist narrative techniques obscure a text’s “commitment to the ordinary” (Olson 3) and therefore blind the reader to ‘the way things are’ in front of us, Joyce functions as the visual catalyst through which we see his Dublin and gives us a “painterly, discursive order of visual representation” (Knowlson n.p.). My argument will focus on two main points by addressing Joyce’s deviations between realism and imagism and the limits these impose and then, leading on from ideas of “images” of people, by addressing his role as “portrait” artist, in connection with Baudelaire’s idea of “the Painter of Modern Life”. I contend that Joyce, by choosing to objectively represent the ‘real’ through vivid images and movements such as “the swing of his burly body” (45) or “frank rude health glowed in her face” (49), is on the cusp of both realism and imagism, which, I argue, serves to emphasise his allegiance to writing a visual experience of life, rather than favouring a growing tendency to reflect subjectively upon thoughts. It is argued that Joyce is a realist because he represents real life with all its “sordid and harsh aspects of human existence” (Norris 3), but I argue that Dubliners also embraces, to some extent, imagism because he selectively privileges images of the city over dwelling on one’s place in the city, and moreover, he privileges some images over others. Pound writes that “good writing is writing that is perfectly controlled, the writer… uses the smallest possible number of words” (The Serious Artist n.p.) realism is inclined to describe ALL of reality, ins and outs, those we can see and those we can’t, but Joyce focuses on harnessing the essence of life in a single precise, image (like imagism) but while staying true to the detailed nature of reality. Norris defines realism as the “belief that human beings can accurately reproduce, by means of verbal and visual representations… the objective world that is exterior to them” (9) whereas imagism “is not simply a brutal reduction to the real but an act of artifice and workmanship” (Brooker 12) “All art is realism of one sort or another” - Represents the visual in an obvjective manner, like realist art. Art/writing gives shape to chaos of modernity by focusing on the visual image, limits chaos of Dublin by only letting reader/viewer observe some details. Lists. This is a detachment from subject matter and “direct treatment of things” which realists rarely allow themselves but more all-encompassing and descriptive than imagism → “don’t be descriptive, remember that the painter can describe a landscape much better than you can” – this is what Joyce strives for. Modernism “can inject a sense of strangeness and surprise into its portrayal of the most commonplace phenomena” (Felski, qtd in Olson 4) Leading on from this, I argue that the matter of description is where Joyce diverges from Pound’s ideas on the “direct treatment of things”, and I aim to draw parallels between description in the written word and its likeness to detail in the painted picture, a comparison which draws evidence from Joyce’s privileging of visual detail, and between both painter and writer as what Baudelaire calls the “passionate observer”. I argue that both mediums embody the “freedom from sloppiness” that Pound praises Joyce for: the visual image, in any form, is a sharp, defined depiction of life as it is and how we see it. This theory is supported by the statement “if there are exact sciences there are also exact arts, and the grammar of painting is much more definite” (James 746); Joyce strives to privilege the grammar of the visual because it is a much more exact form of expression. The following passage, taken from The Dead, harks back to realist still life paintings of banquets (see Cornelis De Heem, Abraham van Beyeren, George Lance to name a few): “A fat brown goose lay at one end of the table and a the other end, on a bed of creased paper strewn with parsley, lay a great ham […] between these rival ends ran parallel lines of side-dishes: two little minsters of jelly, red and yellow […]a large green leaf-shaped dish with a stalk-shaped handle […] and behind it were three squads of bottles of stout and ale” (197) Joyce’s portrayal of the dinner table is situated only in the visual sphere, presented as descriptive fact; we do not receive any of Gabriel’s opinions upon the nature of the food, despite the fact that The Dead is read through his eyes, nor are we given any other of the five senses. Therefore we see Joyce’s Dubliners privileges the visual through evidence of his objective, opinion-free presentation of what characters see, in the same way that what an artist paints can in no way portray anything other than the visual, and certainly not their opinion. In his essay The Art of Fiction, James presents this similarity as being a “community of method of the artist who paints a picture and the artist who writes a novel” (746); it is implied that the novel fits more under the “community” of visual arts than it does written. It also implies a reciprocity between the acts of reading and viewing. To see a painting allows one to read into the story it paints; to read a book allows a picturing of the visual images it describes in language. 1) Baudelaire talks about Constantin Guy’s sketches of the Crimean War: “I have seen a considerable quantity of these drawings… and thus I have been able to read, so to speak, a detailed account of the Crimean campaign” – This is due o the exactness + detail of the image, can’ get that in realism without to-the-point detail, and don’t get it in Imagism because they don’t describe –. (Baudelaire) - Display life how it is, without bias or motive “the artist moves little or even not at all in intellectual and political circles” (Baudelaire) – if joyce didn’t focus as much on visual then objective depiction of life would become subject to his political inclinations. Draw on catalyst – Pound said “ the artist is the catalyst, which it is important to point out, has no intention”. Gretta and portrait. Gabriel as portrait painter/writer, example in text too. “The only reason for the existence of the novel is that it does attempt to represent life… the same attempt that we see on the canvas of the painter” (James 745). One would presume that a writer would turn to facts to comment on the reality of things but “Joyce recognised that facts can neither adequately reconstitute the world nor totally ‘sum up’ experience” (Olson 34). In order to construct a true representation of life as we see it before our eyes, facts have to be visually transformed into an image, so the reader can easily picture the reality of the life in Dubliners’ by grafting their own visual experiences and memories onto the written image that Joyce creates. 2) Portraits. Descriptive penning of characters as writing their portrait. Evryone defined by physical appearance. Doherty calls this “pure pictorial pastiche – a journalistic report on an artwork – not the real thing, but a verbal copy” (51). Barthes argues that a “dubious fate overwhelms the visual: it too takes shape as the ‘anatomical cataloguing’ of body parts, which, blended together, go to make up the conve Characters “without ‘face’ support create a disembodied disassociated affect” – reader can’t see image, obscured from them. Routine for Joyce. Argue against “dwell on the detail not as some synecdoche for some larger ideal, but as a souce of realism” (Olson 24) – other “ideals” don’t have to be grand but simply reveal something else about character → Tool for painting interior as well as exterior (Fred Manley) so shows real life even more. Araby and light in portrait – sister is “conventional art-image” (Doherty 52). Static nature of faces – bound images, don’t change. Emphasises “freeze frame” effect (paralysis in Dubliners), doesn’t represent duality in time, “an ‘image’ is that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time” → the reader “can no more catch every texual detail than he or she can be cognisant of every element of everyday life” (Olson 35) and narrator is in on this game, as in araby “the boy freely manipulates the portrait … highlighting some elements while blocking out others” (Doherty 52) However CAN’T represent everything simulatenously because narrative is linear so joyce is selective – don’t notice everything about a painting, nor can you paint everything unless it’s a panorama. Pound: “I think he excels most of the impressionist writers because of his more rigorous selection, because of his exclusion of all unnecessary detail” Therefore joyce has to use lists – closest Joyce can get to the all inclusive, present, visual reality of a painting. However this is not to say that Joyce does not invite interpretation of Dubliners. “gaping holes or gaps in the text – semantic abysses – incite readers to fill in the details”. 3) Focus on eyes as most important part of body. I argue that although these familiar set features occur within almost every character - to the extent, Doherty argues, that they “form an automatized part of character delineation” (121) – we must recognise the importance, in Joyce’s portraits, paid to the eyes. I contend that the attention Joyce pays to facial expression is significant because the face is the foundation of the eyes, without which vision from the characters’ perspective would not be possible. Araby’s “paradoxical fusion of vision and blindess” (Doherty 48) Lenehan in Two Gallants. Eyes as judge of body/reality like they are judge of artwork. Pound said Joyce “gives us things how they are” and had “a sharp eye for seeing life as it is” – he transfers that observation of life into straightforward images ready for the reader’s consumption. Even though few are in first person we see things through narrators eyes , privileges vision, we follow their gaze as we only see in the painting what the painter has painted for us. Image “strikes on the imaginative eye” (pound) – privileges visual. 4) Conclusion. Pound: “perfectly controlled… complete clarity and simplicity”