p - California State University, Fresno

advertisement

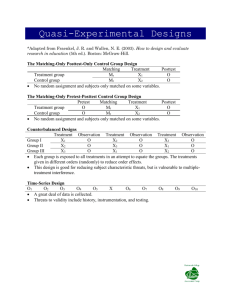

1 A STUDY OF DEVELOPMENT PRACTICES IN SITE-BASED LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS Marc David Barrie California State University, Fresno 2014 2 INTRODUCTION Today’s higher education organizations have become chiefly concerned with succession planning, more specifically, the need for sustainable leadership development strategies that will effectively fulfill the leadership inadequacies of potential leaders (Collins & Holton, 2004; Conger & Benjamin, 1999). As a result, many organizations are committing to implementing training and development strategies that increase mastery of skills, expand perspectives, and ultimately increase the competencies of their leaders and potential leaders (Collins & Holton, 2004; Conger & Benjamin, 1999). Despite the widespread implementation of leadership development programs, research indicates that organizations traditionally spend insufficient time evaluating the effectiveness of their programs and whether such programs actually improve the organization’s performance (Sogunro, 1997). According to Avolio, Avey, and Quisenberry (2010), organizations are typically willing to invest in leadership development when sufficient funds are available. Even a slow economy represents an opportune time to invest in leadership development as it can inspire new strategies for navigating difficult economic times (Avolio et al., 2010). However, in a downturn economy, such as the educational landscape of today, training and development are typically marginalized (Avolio et al., 2010). With limited resources available to public institutions in higher education, it is important to identify cost-efficient ways of ensuring that leadership development programs remain sustainable in spite of diminished funding. When analyzing the return on investment of on-site, off-site, and online leadership development programs Avolio et al. (2010) found that when accounting for cost (fees, travel, loss of work time) and outcomes were factored in, site-based 3 leadership development programs had the highest return on investment. As such, this study explores the effectiveness of site-based leadership development programs in publicly-funded higher education. Purpose of the Study Newly appointed university leaders recognize that the skills required for success in their previous non-administrative roles differ from the skills needed in their new leadership roles (Bray, 2008). According to Hill (2007), lack of proper leadership training, education and experience presents a gap in the skills necessary to transition into these new roles. According to Bolman and Gallos (2011), new leaders report having no time to cultivate their leadership skills on their own, which subsequently perpetuates the problems exposed from inadequate preparation. The California State University (CSU) system currently rests in the shadow of a poor economic climate. In its present state of fiscal uncertainty and declining resources, it is important to plan for leadership succession and to foster new insights that may promote innovative ways for navigating current challenges. Leadership development efforts should be verified to be both effective and cost efficient (Avolio et al., 2010). Without a relevant method for assessing the effectiveness of a leadership program, leaders will continue to undervalue the importance of such programs and fail to see their value (Avolio et al., 2010). As universities look to the future of organizational development, it is imperative that they take steps to ensure the continuance of succession planning through leadership development. Before such measures are adopted, it is important to implement strategies for assessing the effectiveness of such programs. Employing over 43,000 employees, the California State University System is the largest state university system in the country. This study supports Human 4 Resource Development by identifying tools for assessing leadership development programs, illustrating the impact that effective leadership development can have on an organization, and demonstrating that leadership development efforts should be prioritized as a means of creating sustainable leadership. Theoretical Framework In order to adequately evaluate the effectiveness of a leadership development program, it is important to identify an appropriate model to frame the study (Collins & Holton, 2004). Kirkpatrick’s (1959) four-level evaluation model is used to examine: (1) individual reactions of the program; (2) what the participants learned; (3) how the participant’s behavior changed; and (4) links changed behavior to organizational performance (Kirkpatrick, 1959, 2004); all of which have been identified as key variables in demonstrating transfer of knowledge (Collins & Holton, 2004; Kirkpatrick, 1959, 2004). The Kirkpatrick Model recognizes four distinct behavioral variables that are identified with transfer and learning. However, Kirkpatrick’s model does not include a component for identifying organizational performance -the effectiveness of an organization in achieving outcomes as identified by its strategic goals, or the realization of a return on investments (Holton, 1996). Building off the framework of Kirkpatrick’s model, Guskey (2000) suggested that effective professional development models should include analysis of five critical levels of information: (1) Participant Reaction; (2) Participant Learning; (3) Organizational Support; (4) Application of New Skills; and (5) Learning Outcomes. It is through this approach that the Guskey model has incorporated a component for organizational support, reflecting the integration of development within the context of the institution. As on-site leadership development programs have been shown to positively impact the transference of 5 training, measuring organizational support, context, and the impact of using a cohort model is relevant in establishing the effectiveness of leadership development programs (Avolio et al., 2010). Definitions Leadership Development For the purposes of this study, Leadership Development is defined as “Every form of growth or stage of development in the life cycle that promotes, encourages, and assists the expansion of knowledge and expertise required to optimize individual leadership potential and performance” (Brungardt, 1996, p. 83). Senior Leadership For the purposes of this study, senior leadership refers to executive level leadership (Chancellor, President, Vice President, Provost, Vice Chancellor). 6 METHODS Context of Study The study was conducted with the California State University (CSU) system, the largest state college system in the country. According to the California State University Office of the Chancellor (2011), the CSU serves over 420,000 students and stretches across California with 8 campuses located in northern California (Chico, East Bay, Humboldt, Maritime Academy, Sacramento, San Francisco, San Jose, Sonoma); 4 in central California (Fresno, Monterey Bay, San Luis Obispo, and Stanislaus); and 11 in the southern California area (Bakersfield, Channel Islands, Dominguez Hills, Fullerton, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Northridge, Pomona, San Bernardino, San Diego, and San Marcos). Though each campus has its own character, all campuses offer undergraduate and graduate education for professional and occupational goals in addition to broad liberal education (California State University Office of the Chancellor, 2011). The CSU provides more than 1,800 bachelors, masters and doctoral degree programs as well as a variety of teaching and school service credential programs (California State University Office of the Chancellor, 2011). The CSU system employs over 43,000 faculty and staff. It is the responsibility of each campus to develop, fund, and maintain its own professional development and leadership development programs. Presently, eight CSU campuses offer leadership development programs. All of the eight participating campuses utilize the same Leadership Development curricula which incorporate five learning outcomes: Challenging the Process, Inspiring a Shared Vision, Enabling Others to Act, Modeling the 7 Way, and Encouraging the Heart. For the purposes of this study, each of the participating campuses will be referred to using a pseudonym. Alpha State University With over 8,000 undergraduate and graduate students, Alpha State employs over 850 faculty, staff and administrators. With the inception of its leadership development program 2 years ago, Alpha has partnered with Kappa State and Gamma State for a collaborative leadership development program. As part of the collaborative, the Presidential Cabinet of Alpha nominates 10 administrators to join a combined cohort of 30 participants. The program spans 7 months and contains six different sessions in the following content areas: developing the leader within, leadership perspectives, leading and motivating teams, thinking holistically, leadership communication, and managing power and organizational politics. In addition to its course content, participants also complete a group project designed to address a campus need. Each project is selected by the President’s Cabinet (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Beta State University With over 14,000 undergraduate and graduate students, Beta State employs over 1,200 faculty, staff and administrators. Beta has partnered with Epsilon State and Delta State to form a leadership development collaborative. The Presidential Cabinet from Beta State nominates eight administrators each year to form a combined cohort (three campuses) of 24 participants. The program spans 6 months and contains different sessions whose content includes leadership principles, interpersonal and people management skills, internal and external customer service, effective 8 planning and communication. Also covered were labor issues, such as the Higher Education Employer-Employee Relations Act (HEERA), labor relations and contract administration and resource management according to CSU funding and budget practices (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Gamma State University With over 21,000 undergraduate and graduate students, Gamma State employs over 2,000 faculty, staff and administrators. As part of a collaborative between the CSU campuses of Kappa State and Alpha State, the Presidential Cabinet of Gamma nominates 10 administrators to join a combined cohort of 30 participants. The program spans7 months and contains six different sessions in the following content areas: developing the leader within, leadership perspectives, leading and motivating teams, thinking holistically, leadership communication, and managing power and organizational politics. In addition to its course content participants also complete a group project designed to address a campus need. Each project is selected by the Presidential Cabinet (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Delta State University With over 35,000 undergraduate and graduate students, Delta State employs over 3,400 faculty, staff and administrators. Delta has partnered with Beta State and Epsilon State to form a leadership development collaborative. The Presidential Cabinet from Delta State nominates eight administrators each year to form a combined cohort (three campuses) of 24 participants. The program spans 6 months and contains different sessions whose content includes leadership principles, interpersonal and people 9 management skills, internal and external customer service, effective planning and communication. Also covered were labor issues, such as the state’s Higher Education Employer-Employee Relations Act (HEERA), labor relations and contract administration and resource management according to CSU funding and budget practices (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Epsilon State University With over 20,000 undergraduate and graduate students, Epsilon State employs over 2,000 faculty, staff and administrators. Epsilon has partnered with CSUs Beta State and Delta State to form a leadership development collaborative. The Presidential Cabinet from Epsilon State nominates eight administrators each year to form a combined cohort (three campuses) of 24 participants. The program spans 6 months and contains different sessions whose content includes leadership principles, interpersonal and people management skills, internal and external customer service, effective planning and communication. Also covered were labor issues, such as the state’s Higher Education Employer-Employee Relations Act (HEERA), labor relations and contract administration and resource management according to CSU funding and budget practices (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Kappa State University With over 5,000 undergraduate and graduate students, Kappa State employs over 750 faculty, staff and administrators. As part of a collaborative between the CSU campuses of Gamma State and Alpha State, the Presidential Cabinet of Kappa State nominates 10 administrators to join 10 a combined cohort of 30 participants. The program spans 7 months and contains six different sessions in the following content areas: developing the leader within, leadership perspectives, leading and motivating teams, thinking holistically, leadership communication, and managing power and organizational politics. In addition to its course content participants also complete a group project designed to address a campus need. Each project is selected by the Presidential Cabinet (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Lambda State University With over 36,000 undergraduate and graduate students, Lambda State employs over 3,300 faculty, staff and administrators. Lambda provides a leadership development program that is made up of a series of eight workshops geared at leadership development. Each session supports a different need, allowing all campus leaders to self-select individual workshops relevant to their needs. The number of participants varies as individuals may choose to attend one or multiple workshops throughout the year (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Omega State University With over 9,700 undergraduate and graduate students, Omega State employs over 1,100 faculty, staff and administrators. Omega has developed an extensive three track leadership development program designed for emerging, new, and experienced leaders. It is an extensive program that combines classroom and experiential learning, tailored to the individual’s professional development needs. Its courses are designed to support the core competencies required for an effective leader at Omega State: 11 Managing Yourself, Managing Your Team, Managing the Work, and Managing Collaboratively. Participants are selected by Executive Council (California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources, 2012). Research Design This study used a mixed-method research approach employing survey implementation for quantitative methods of data gathering while telephone interviews were used to collect qualitative data. The survey was used to identify leadership practices pre and post leadership development program participation. Research questions 1, 2, 3, were answered through interview questions regarding participant perceptions of the impact of the site-based program on the development of their leadership skills (see Appendix C). Research questions 6 and 7 were answered by the survey, which was used to identify changes in leadership practices following the completion of a site-based leadership development program (see Appendix A). Research questions 4 and 5 were answered through both interview questions and the survey (see Appendix A & C). Research Questions This study was intended to answer seven research questions through surveys and interviews (Table 1). Table 1 Research Questions, Instruments and Data Analysis Research Question Has participation in the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted Instrument Questions Interview 5 Analysis Content 12 in increased support for and commitment to their organization? Analysis Has participation in the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in increased job satisfaction? Interview 3 Content Analysis Was the site-based CSU leadership development program meaningful for the participant? Interview 2 Content Analysis Has the site-based CSU leadership development program produced significant learning of leadership skills? Survey Interview Themes 1-5, 1 t-Test Content Analysis Has the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in the application of leadership skills? Survey Interview 1-48, 4 t-Test Content Analysis Are there differences among the programs that produce significant differences in the learning of leadership skills? Survey Themes 1-5 ANOVA Are there differences among programs that resulted in the application of newly acquired leadership skills? Survey 1-24 ANOVA Participants/Sample With the continuing demand for higher education to develop future leaders in a climate of limited resources, organizations must identify ways of measuring effectiveness when evaluating leadership development programs. Research suggested that site-based programs yielded a greater return on investment than external programs, and that there is a positive relationship between employer-provided professional development and intrinsic motivation (Avolio et al., 2010; Dysvik et al., 2010). This study focused on participants of site-based leadership development programs currently being offered at California State Universities. The California State University (CSU) is the largest state college system in the country with 23 campuses located throughout the state. Among the CSU campuses, eight offer site-based leadership development 13 programs. This study focused on graduates from the eight CSU campuses with leadership development programs whose pseudonyms are; Alpha State, Beta State, Gamma State, Delta State, Epsilon State, Kappa State, Lambda State, and Omega State. Participants were comprised of individuals who elected to participate in this study, had successfully completed a campus-based leadership development program in the past 2 years (from one of the aforementioned eight CSU campuses), and maintained employment at the campus from which they had completed the leadership program. Instrumentation The Leadership Practices Inventory-Self (LPI-Self), developed by Kouzes and Posner (2007) was used to identify leadership skills and abilities of participating leaders. The LPI is based on five leadership practices believed to be common among successful leaders. These five practices include Challenging the Process, Inspiring a Shared Vision, Enabling Others to Act, Modeling the Way, and Encouraging the Heart (Leong, 1995). Each response on the instrument was scored on a 10-level Likert scale, 1 being lowest and 10 being highest. In terms of scoring each numerical value is represented as follows: 1= almost never, 2=rarely, 3=seldom, 4=once in a while, 5=occasionally, 6=sometimes, 7=fairly often, 8=usually, 9=very frequently, 10=almost always. In order to identify the effectiveness of leadership development programs, it was important to capture LPI scores both pre and post program participation. Although normally pretests are administered prior to an intervention, time constraints prevented the administration of these tests in the typical method. In order to capture the data of pre and posttests in the 14 given time constraints, this study employed retrospective pretest (RPT) (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). The RPT was administered at the same time as the posttest, that is, respondents were asked to answer questions about their leadership practices or skills after participating in the leadership development program (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). They were then asked to think back to their understanding prior to participating in the program; providing a retrospective pretest (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). The advantage of the RPT was that it was time sensitive for both the researcher and the participant. The researcher was able to capture data in one survey alleviating time constraints from multiple tests (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). This time sensitive nature is also an advantage for participants as their time commitment is reduced from two tests into one. The RPT can also present an advantage in that it aids in avoiding a response-shift effect that occurs when the evaluation standard of the participant changes significantly during an intervention (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). According to Lamb (2005) the RPT increases pretest validity as it eliminates the possibility of a participant misunderstanding the basic terms, concepts or questions associated with a pretest survey. Pilot Study A pilot study was conducted to establish the content validity and internal consistency of the LPI (Polit, Beck, & Hungler, 2001). The instrument was given to a group of administrators to test the appropriateness of the survey (on a small scale) in order to address any logistical issues involved with deploying the online instrument (Polit et al., 2001). The pilot group reported that the instructions for taking the LPI were clear and that all questions were understandable. 15 Data Analysis The quantitative data were collected via online surveys, extracted from Survey Monkey and placed into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for analysis. Each of the leadership development programs were coded by type to differentiate between program characteristics. Analysis focused on the relationship between participation in a site-based leadership development program, leadership skills, and participant perceptions regarding the site-based leadership development program. Using 41 managers in two medium-size hospitals, Smith (1991) found positive and significant correlations between the leadership behaviors in the LPI and three outcome variables: organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and productivity. Smith also used stepwise regression to discover that Modeling the Way accounted for the greatest amount of variance in productivity and Enabling Others to Act explained the greatest amount of variance around both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. For this study, similar analysis was used on the quantitative data. Content analysis was used for the qualitative data collected via telephone interviews. The data were coded by theme and analyzed for the reoccurrence of themes using Pope and Mays’s (2006) five-stage Framework Analysis. The five-stage method of analysis consisted of (1) organizing the raw data, (2) identifying thematic framework, (3) indexing the data, (4) charting the data, and (5) interpreting the data (Pope & Mays, 2006). 16 Limitations The study was limited to participants who self-selected to complete the survey, thereby including some bias in the study. Due to the limited number of campuses involved in site-based leadership development, the N was small. Among the 59 participants, the majority of responses was collected from administrators (N = 41; 70.67% of Total Responses). Additionally, participants that were no longer employed at the campus of which their leadership development training was completed were not contacted to participate. 17 RESULTS Using surveys and semi-structured interviews, data was collected and analyzed for the purposes of identifying the impact of site-based leadership development in the CSU. The Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI) was distributed electronically to participants from eight CSU campuses. The LPI is a 24-item instrument. The eight campuses were selected for having site-based leadership development programs. Interviews were also conducted via 15-minute telephone conversations. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, coded for themes, and analyzed for reoccurrence of main ideas and themes. Demographics In the course of the study, participants from eight CSU campuses (see Table 2) completed the Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI) while 11 of the 59 also participated in a 15-minute interview. Although course content among the eight campuses was consistent, seven of the eight campuses utilized a cohort model for their program. Among those participating in the survey, the largest number of respondents were administrators (N=41), followed by staff (N=15), and faculty (N=2) (see Table 3). The majority of respondents were female (N=34) (see Table 4) with the majority of respondents reporting an ethnicity of White (N=33) (see Table 5). 18 Table 2 Frequency Distribution of Responses by Campus Campus Frequency Percent of Total Alpha State 9 15.25 Beta State 3 5.06 Gamma State 7 11.66 Delta State 4 6.78 Epsilon State 3 5.06 Kappa State 5 8.47 Lambda State 8 13.56 Omega State 20 33.70 Total 59 Table 3 Frequency Distribution of Responses by Position Position Frequency Percent of Total Administrator 41 70.67 Staff 15 25.86 Faculty 2 3.37 Missing 1 1.72 Total 59 19 Table 4 Frequency Distribution of Responses by Gender Gender Frequency Percent of Total Female 34 57.63 Male 25 42.37 Total 59 Table 5 Frequency Distribution of Responses by Ethnicity Ethnicity Frequency Percent of Total White 33 56.86 Declined to State 7 12.07 African American 5 8.62 Asian 5 8.62 Hispanic 5 8.62 American Indian or Alaskan Native 2 3.45 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 1 1.72 Missing 1 Total 59 Research Questions Research Question #1: Has participation in the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in increased support for and commitment to their organization? To determine whether participation in a leadership development program resulted in increased support for the organization, participants were interviewed and asked the open-ended question: How has your 20 participation in the leadership development program impacted your engagement with the university? Among the highest reported responses (by theme) were: gained a better understanding of senior leadership, gained a better understanding of university challenges, provided a chance to build a relationship with senior leaders, and gained a better appreciation for senior leadership (see Table 6). Table 6 How Participation Impacted Engagement with the University Response Better understanding of senior leadership Relationship building with senior leaders Better understanding of university challenges Better appreciation for senior leadership Increased appreciation of my current role Clearer understanding of strategic planning Better appreciation for planning efforts Total Frequency 6 Percent of Total 18.75 6 18.75 5 15.63 5 15.63 4 12.50 3 9.38 3 9.38 32 100 Research Question #2: Has participation in the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in increased job satisfaction? To determine whether participation in a leadership development program resulted in increased job satisfaction, participants were interviewed and asked: How has your participation in the leadership development program impacted your engagement in your current role? 21 Among the highest reported responses were: more aware of how I communicate, more comfortable communicating with senior leadership, improved understanding of university challenges, and more confidence in abilities (see Table 7). Table 7 How Participation Impacted Engagement in Current Role Response Frequency Percent of Total More confidence in abilities 7 18.92 More comfortable communicating with 6 16.22 6 16.22 More aware of how I communicate 5 13.51 New perspective for how I lead others 4 10.81 Better appreciation for role in the 4 10.81 3 8.11 2 5.41 37 100 senior leadership Improved understanding of university challenges university Learned how to communicate more effectively Created communication networks on campus Total Research Question #3: Was the site-based CSU leadership development program meaningful for the participant? To analyze whether participation in a leadership development program was meaningful, participants were interviewed and asked: How 22 would you say that the leadership development program was relevant to your current role? Among the highest reported responses were: gave me an opportunity to see how things are done in other work groups, taught me about leadership challenges, taught me better ways to communicate with staff, taught me how to communicate with senior leadership, and gave me new perspectives for dealing with challenges (see Table 8). Table 8 How the Leadership Development Program was Relevant to Current Role Response Frequency Percent of Total Taught me how to communicate with senior leadership 7 20.59 Taught me better ways to communicate with staff 6 17.65 Taught me about leadership challenges 5 14.71 Gave me new perspectives for dealing with challenges 5 14.71 Gave me an opportunity to see how things are done in other work groups 5 14.71 Taught me about conflict resolution 3 8.82 Showed me ways to improve relationships 3 8.82 Total 34 100 Research Question #4: Has the site-based CSU leadership development program produced significant learning of leadership skills? In order to identify learning of leadership skills, pretest and posttest responses were aggregated into one of five LPI learning themes and analyzed using a dependent t-test. The aggregated responses from each of 23 the five learning themes were self-reported measures on a 10-level Likert scale (see Table 9). Across all five themes, there was a significant difference in mean responses, which increased from pretest to posttest. Model the Way (t = -9.176, df = 58, p< .001); Inspire Shared Vision (t = 8.881, df = 57, p< .001); Challenge the Process (t = -7.390, df = 58, p< .001); Enable others to Act (t = -8.132, df = 58, p< .001); Encourage the Heart (t = -9.327, df = 58, p< .001). Table 9 Mean, Number, and Standard Deviation for the LPI Learning Themes Pretest and Posttest Item Model the Way Pretest Posttest Inspire Shared Vision Pretest Posttest Challenge the Process Pretest Posttest Enable Others to Act Pretest Posttest Encourage the Heart Pretest Posttest Mean SD N 8.03 8.81 0.947 0.770 59 59 7.40 8.49 1.371 1.194 58 58 7.42 8.38 1.411 1.214 59 59 8.39 9.06 0.791 0.635 59 59 7.96 8.88 1.089 1.002 59 59 To further analyze learning of leadership skills, participants were interviewed and asked: How do you believe that the leadership development program impacted your learning of leadership skills? Among the highest reported responses were: group discussions allowed for better 24 understanding, hearing leadership perspectives was valued, and hearing peer perspectives on issues was valuable (see Table 10). Table 10 How Leadership Development Program Impacted Learning Theme Frequency Percentage Group discussion allowed for better understanding 7 19.44 Hearing leadership perspectives was valuable to learning 6 16.67 Hearing peer perspectives on campus challenges was valuable 6 16.67 Role playing allowed for better understanding 5 13.89 Presented an opportunity to ask questions 4 11.11 Problem solving as a group was helpful 3 8.33 Case studies were relevant and meaningful 3 8.33 Literature was relevant and meaningful 2 5.56 Total 32 100 Research Question #5: Has the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in the application of leadership skills? To address this research question, a pretest and posttest was administered to explore the changes in application of leadership skills. For 25 all skills measured, there was a significant change (p < 0.001). Table 11 displays the change in means from pretest to posttest and Table 12 the test for significance. While all items showed significance, Figure 1 shows the skills with the largest change in means between pre and posttest. The items with the greatest change between pre and posttest were: Talk about trends (t = -6.041, df = 58, p< .001); Describe a compelling image of the future (t = 7.069, df = 58, p< .001); Appeal to others to share exciting dream of the future (t = -6.137, df = 58, p< .001); Ask for feedback on how my actions affect other peoples performance (t = -7.999, df = 58, p< .001); Show others how long-term interests can be realized with shared vision (t = -8.585, df = 58, p< .001); I experiment and take risks even when there is a chance of failure (t = -6.870, df = 58, p< .001); and I ensure that people grow in their jobs by developing themselves (t = -8.221, df = 58, p< .001). To further analyze application of leadership skills, participants were interviewed and asked: How do you believe that the leadership development program impacted your application of leadership skills? Among the highest reported responses were: increased my understanding of leadership challenges, challenged how I interact with my employees, and became more confident in decision making (see Table 13). Research Question #6: Are there differences among the programs that produce significant differences in learning of leadership skills? In order to identify differences in learning of leadership skills among programs, posttest responses were aggregated into one of five LPI learning themes 26 Table 11 Mean, Number and Standard Deviation for LPI Items with Largest Change in Means from Pretest to Posttest Item Talk about trends Pretest Posttest Describe a compelling image of the future Pretest Posttest Appeal to others to share exciting dream of the future Pretest Posttest Ask for feedback on how my actions affect other peoples performance Pretest Posttest Show others how long-term interests can be realized with shared vision Pretest Posttest I experiment and take risks even when there is a chance of failure Pretest Posttest I ensure that people grow in their jobs by developing themselves Pretest Posttest Mean SD N 7.47 8.49 1.675 1.369 59 59 7.19 8.27 1.624 1.460 59 59 7.12 8.32 1.733 1.345 59 59 6.47 7.90 1.942 1.594 59 59 6.78 8.24 1.743 1.343 59 59 7.02 8.03 1.889 1.671 59 59 7.88 8.95 1.314 0.990 59 59 27 Table 12 Test for Significance of LPI Items with Largest Change in Means from Pretest to Posttest Item t df p 6.041 7.069 58 58 .000 .000 6.137 58 .000 Ask for feedback on how my actions affect other peoples performance 7.999 58 .000 Show others how long-term interests can be realized with shared vision 8.585 58 .000 I experiment and take risks even when there is a chance of failure 6.870 58 .000 I ensure that people grow in their jobs by developing themselves 8.221 58 .000 Mean Talk about trends Describe a compelling image of the future Appeal to others to share exciting dream of the future 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Pretest Posttest 2 4 8 10 11 21 22 LPI Item Number Figure 1. Change in mean score for LPI Items with the greatest change from pretest to posttest 28 Table 13 How Leadership Development Program Impacted Application of Leadership Skills Response Increased my understanding of Frequency Percent of Total 7 20.00 5 14.29 More confident in decision making 5 14.29 Changed my expectations of senior 4 11.43 4 11.43 4 11.43 3 8.57 More confident in resolving conflict 3 8.57 Total 35 leadership challenges Challenged the way that I interact with my employees leadership Made me open to accepting new ideas More confident about speaking openly Changed the way that I communicate with my employees 100 and analyzed by program type to determine differences in reported outcomes. Using an ANOVA, program types were divided into two groups; group 1 (cohort based) and group 2 (non-cohort based). The aggregated responses from each of the five learning themes were self-reported measures on a 10-level Likert scale. Across all five themes, there were no significant differences in mean scores in learning between cohort and non- 29 cohort type programs (see Table 14). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in learning across all eight campuses (see Table 15). Table 14 Means, Standard Deviations, Sample Sizes for the LPI Learning Themes by Program Type Theme Mean SD N Cohort 8.82 0.765 51 Non-Cohort 8.73 0.855 8 8.81 0.770 59 Cohort 8.50 1.248 51 Non-Cohort 8.10 1.046 8 8.45 1.222 59 Cohort 8.46 1.18 51 Non-Cohort 7.88 1.37 8 8.38 1.21 59 Cohort 9.07 0.664 51 Non-Cohort 8.98 0.422 8 9.06 0.635 59 Cohort 8.85 1.05 51 Non-Cohort 9.06 0.594 8 8.88 1.003 59 Model the Way Total Inspire Shared Vision Total Challenge the Process Total Enable Others to Act Total Encourage the Heart Total 30 Table 15 Summary Table for ANOVA using the LPI Learning Themes as the Dependent Variable and Program Type as the Independent Variable Sum of Mean Source Squares df Square F Model the Way Between Groups 0.062 1 0.062 Within Groups 34.335 57 0.602 Total 34.397 58 Between Groups 1.084 1 1.084 Within Groups 85.497 57 1.500 Total 86.580 58 Between Groups 2.399 1 2.399 Within Groups 83.115 57 1.458 Total 85.514 58 Between Groups 0.055 1 0.055 Within Groups 23.312 57 0.409 Total 23.367 58 0.318 1 p 0.103 0.750 0.722 0.399 1.646 0.205 0.135 0.714 0.313 0.578 Inspire Shared Vision Challenge the Process Enable Others to Act Encourage the Heart Between Groups 0.318 31 Within Groups 57.979 57 Total 58.297 58 1.017 Research Question #7: Are there differences among programs that resulted in the application of newly acquired leadership skills? To identify any differences in the application of leadership skills, posttest responses from all 24 LPI items were analyzed by program type to determine differences in reported outcomes. Using a One-Way ANOVA, program types were divided into two groups: group 1 (cohort based) and group 2 (non-cohort based). Across 24 items, there were no statistically significant differences in application of leadership skills between cohort and non-cohort type programs (see Appendix D, Tables 16 and 17). However, there was a notable difference (but not statistically significant) regarding listening to diverse points of view (F = 3.638, df = 1, 57, p = .062) between those who participated in a cohort based program (M = 9.16) and those who participated in a non-cohort based program (M = 8.50). Other Analysis During the course of this study, two other areas of interest (not included in the seven research questions) were found. A One-way ANOVA of posttest scores by gender and by position were analyzed for significance. By position, there were no significant differences on any of the items. By gender, women scored significantly higher in response to LPI Item 1: I set a personal example of what I expect from others (F = 4.844, df = 1, p = 0.032). 32 DISCUSSION Summary of Findings Many of today’s leaders have reported frustration and time lost from feeling ill-prepared for their new leadership roles. As Collins and Holton (2004) discovered, administrators who participated in leadership development differed greatly in leadership ability and content knowledge from their peers. This study explored the effectiveness of site-based CSU leadership development programs and was guided by seven research questions. A mixed-methods approach was used to analyze the data collected. The survey for this study was the LPI Instrument, which collected data from the leadership development program participants from eight CSU institutions. Overall, survey results revealed a significant increase in learning and application of leadership skills among all groups with no significant differences in outcomes between program types (cohort vs. non-cohort). Interview responses showed that senior leadership and peer debriefing contributed to positive appraisals of leadership development. Additionally, there were no significant differences between program types (cohort vs. non-cohort), campus, position, ethnicity or gender that resulted in differences in the learning or application of leadership skills. Conclusions Research Question #1: Has participation in the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in increased support for and commitment to their organization? 33 From the open-ended responses, participants in site-based leadership development programs indicated that they felt they had increased organizational support in the following way: gained a better understanding of senior leadership (18.75% of total responses), were provided a chance to build a relationship with senior leaders (18.75% of total responses), gained a better understanding of university challenges (15.63% of total responses) and gained a better appreciation for senior leadership (15.63% of total responses). The three highest responses pertaining to interaction with senior leadership (53.13% of total responses) indicated that interactions with senior leadership contributed to increased support and commitment to the organization on the part of the participants. Essentially, these responses suggest that engagement with senior leadership positively impacts engagement with the organization. Current literature underscores these findings by suggesting that leaders who are considerate of others and spend time interacting and developing their employees are most likely to increase engagement throughout their organization (Webb, 2007). Furthermore, Fuller et al. (2006) identified Perceived Organizational Support (POS) to be a factor in influencing employee attachment to an organization. According to Dysvik et al. (2010), when employees perceived employer-provided training programs to be meaningful and relevant for developing their professional skills, a positive relationship between employer-provided professional development and employee work effort emerged. Further, Dysvik et al. discovered that beyond the impact of training itself, employees become motivated to reciprocate for professional development with quality work for the organization. 34 Research Question #2: Has participation in the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in increased job satisfaction? A content analysis of the participant interview responses revealed that participation in site-based leadership development programs increased job satisfaction among respondents by supporting program participants to become: more confident in their ability (18.92% of total responses), more comfortable communicating with senior leadership (16.22% of total responses), understanding of university challenges (16.22% of total responses) and more aware of how they communicate (13.51% of total responses). In reviewing the four highest responses, 35% of the total participant responses attributed increased confidence to increased job satisfaction. According to McCollum and Kajs (2009), self-efficacy is a construct tied to success in learning and success in work. The more successful and dedicated a leader is in the pursuit of their professional development the more successful they will be in their professional role (McCollum & Kajs, 2009). McCollum and Kajs noted that without a sense of efficacy, leaders will not pursue challenging goals and will not attempt to surpass obstacles that get in the way of such goals. The selected site-based leadership development programs involved in this study all integrated leadership development into the context of their organizations. The response data supports the current literature in identifying self-efficacy (gained from leadership development) as a contributor to job satisfaction. Silver et al. (2009) contended that with a greater sense of support and confidence, a new leader is likely to report greater motivation to gain mastery over their position. 35 Research Question #3: Was the site-based CSU leadership development program meaningful for the participant? A content analysis of the interview responses revealed that participants identified their leadership development experiences to be meaningful because they: learned how to communicate with senior leadership (20.59% of total responses), learned better ways to communicate with their staff (17.65% of total responses), learned about leadership challenges (14.71% of total responses), had an opportunity to see how things operate in other work groups (14.71% of total responses), and learned new perspectives for dealing with challenges (14.71% of total responses). El-Ashmawy and Weasenforth (2010) suggested that meaningful training focused on the more relevant topics in depth and with contextual implications. This training customized to their contexts provided the participants with a more rounded view of how business is conducted (ElAshmawy & Weasenforth, 2010). Collins and Holton (2004) found that for training to be meaningful it should be adapted to participant ability and learning style (Collins & Holton, 2004). Organizations that foster managerial leadership development programs with favorable conditions for transfer, clear training objectives, and address the training within the context of the organization strategic goals, will produce substantial outcomes. As noted earlier, the impact of interacting with senior leadership increased confidence, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment among participants. Essentially, responses suggested that engagement with senior leadership positively impacted engagement for and within the 36 organization and was ultimately meaningful for the participants. Webb (2007) asserted that leaders who become involved in developing their employees are most likely to increase engagement throughout their organization. Further, higher levels of motivation and engagement may be achieved when leaders provide recognition and appreciation for abilities and contributions to the organization (Webb, 2007). Research Question #4: Has the site-based CSU leadership development program produced significant learning of leadership skills? To analyze learning of leadership skills, the LPI themes were examined. In this study, all five leadership practice themes showed significant improvement between pre and posttests after completing leadership development. According to Leong (1995), the five common leadership practices (followed by the data analysis results) follow: Model the Way (t = -9.176, df = 58, p< .001), Inspire Shared Vision (t = -8.881, df = 57, p< .001), Challenge the Process (t = -7.390, df = 58, p< .001), Enable Others to Act (t = -8.132, df = 58, p< .001), and Encourage the Heart (t = 9.327, df = 58, p< .001). These results indicate there was an impact on the learning of leadership skills. A content analysis was conducted to further identify the impact of site-based leadership development programs on the learning of leadership skills. It was reported through the interview scores that learning was impacted from: group discussions, which allowed for better understanding (19.44% of total responses), hearing leadership perspectives (16.67% of total responses), and hearing peer perspectives related to varied issues (16.67% of total responses). 37 Drew (2010) found that well-contextualized programs provide a useful forum for sharing new and relevant information while allowing for the development of problem solving strategies a very important leadership skill. This developed skill increases organizational capacities to develop and sustain leaders capable of thriving in uncertain times, handling complex situations, engaging organizations in common visioning, and building sustainable leadership (Drew, 2010). When given relevant tools and training, Dysvik et al. (2010) determined that employee effort improved to the benefit of the individuals and the organization. Research Question #5: Has the site-based CSU leadership development program resulted in the application of leadership skills? All LPI items showed a significant change (p < 0.001), yet the items with the greatest change following participation in leadership development were: Talk about trends (t = -6.041, df = 58, p< .001); Describe a compelling image of the future (t = -7.069, df = 58, p< .001); Appeal to others to share exciting dream of the future (t = -6.137, df = 58, p< .001); Ask for feedback on how my actions affect other peoples performance (t = 7.999, df = 58, p< .001); Show others how long-term interests can be realized with shared vision (t = -8.585, df = 58, p< .001); I experiment and take risks even when there is a chance of failure (t = -6.870, df = 58, p< .001); and I ensure that people grow in their jobs by developing themselves (t = -8.221, df = 58, p< .001). The interview responses revealed that participation in site-based leadership development impacted the participants by: increasing their understanding of leadership challenges (20% of total responses), challenging how they interacted with their employees (14.29% of total 38 responses), and providing opportunities to become more confident in decision making (14.29% of total responses). The survey responses with the greatest increases in mean were related to shared vision. Interview responses corroborated the survey findings as 20% of total responses reflected understanding of leadership challenges (shared vision with senior leadership) and 14.29 % of total responses reflected challenging the way they interact with their employees (shared vision with subordinates). Essentially, individuals may learn about shared vision when senior leaders model the behavior and practice for learners. Solansky (2010) found that mentoring and coaching provide important elements of leadership development and underscore the importance of evaluating leadership skills. Further, Silver et al. (2009) identified that with a greater sense of support and confidence, a leader is likely to report greater motivation to gain mastery in their role. Research Question #6: Are there differences among the programs that produce significant learning of leadership skills? Across all five themes, there were no significant differences in mean scores in learning between cohort and non-cohort type programs. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in learning across all eight campuses. As all participating leadership development programs offered contextual site-based learning and the integration of senior leadership perspective, these findings are consistent with the research of Collins and Holton (2004) who asserted that leadership training interventions that utilize relevant knowledge and skill-based outcomes produce positive outcomes. 39 Leader development programs (non-cohort type programs) tend to focus on individual-level development concepts such as the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to assume leadership roles (Reichard & Johnson, 2011). In contrast to leader development (cohort-based program), Reichard and Johnson pointed out that leadership development is largely centered on building Social Capital for the development of effective networks. Leadership development focuses on harnessing the collective capacity of the organization using interpersonal competence (Reichard & Johnson, 2011). Although leadership development (cohort) and leader development (non-cohort) programs may achieve similar learning outcomes, Drew (2010) found that organizational capacities can be increased when programs provide a useful forum (cohort) for sharing new and relevant information while concurrently allowing for the development of problem solving strategies (non-cohort). Research Question #7: Are there differences among programs that resulted in the application of newly acquired leadership skills? Although there were no statistically significant differences in application of leadership skills between cohort and non-cohort type programs, there was a notable difference (but not statistically significant) regarding listening to diverse points of view (F = 3.638, df = 1, 57, p = .062) between those who participated in a cohort based program (M = 9.16) and those who participated in a non-cohort based program (M = 8.50). These findings are supported by the research of Avolio et al. (2010) who suggested that the ongoing support and reinforcement of training (found in the cohort model) increased the positive impact of training. As the cornerstone of leadership development revolves around an ability to listen 40 and assimilate outside perspectives into decision making, the cohort model aids in the reinforcement of the practice of listening to diverse perspectives. Other Research Findings In the course of this study, two areas of interest (not included in the research questions) were identified at the time of data analysis and included differences in gender and position held by the respondent. Posttest scores were analyzed by gender and by position to detect any significance differences in posttest scores by group. By position, there were no significant differences on any of the items. By gender, females scored significantly higher than males in response to LPI Item 1: I set a personal example of what I expect from others (F = 4.844, df = 1, p = 0.032). As 70% of the participants in this study were administrators, 25.86% were staff and 3.37% were faculty, the sample may have lacked the diversity, in the category of position, necessary to identify significant differences in these groups. As Webb (2007) found, leaders can increase organizational engagement by modeling desirable behaviors. When attributed charisma was combined with the factors of intellectual stimulation, individual consideration, and contingent reward, administrative staff members were motivated toward extra effort (Webb, 2007). Recommendations Implications for Practice As senior leadership interactions constituted a reoccurring theme throughout all interview responses, future leadership development programs should consider integrating opportunities to network with senior 41 leaders. The presence of senior leadership increased engagement and commitment among participants and resulted in a mean improvement of reported leadership practices. Furthermore, as site-based programs provide contextual value for learning, programs should explore the adoption of sitebased designs. As the site-based design allows for participants to engage one-another during and outside of the learning module, it promotes similar benefits of cohort-based programs in the social-networking context. This study has identified an effective tool (LPI) in assessing the leadership development outcomes. As the LPI has successfully captured leadership practices, it can be used to measure both the application of skills as well as the incidence. As application and incidence go hand in hand with opportunity, the LPI may be utilized as a tool for assessing congruency between training and application. Implications for Future Research As this study was limited to one public university system, future research should be focused on site-based leadership development programs from both public and private universities. Further, a comparative study should be explored to identify differences in outcomes from site-based, externally provided, and online leadership development programs. As this study identified the impact that senior leadership has on motivation, engagement, loyalty, and satisfaction, an investigation of organizational size and leadership development outcomes should be explored. This study did not account for prior training, leadership experience, or age. As these variables may impact the outcome of leadership development training each should be explored. 42 REFERENCES Alliger, G. M., & Janak, E. A. (1989). Kirkpatrick’s levels of training criteria: Thirty years later. Personnel Psychology, 42, 331-342. Amey, M. J., VanDerLinden, K. E., & Brown, D. F. (2002). Perspectives on community college leadership: twenty years in the making. Community college journal of research and practice, 26, 573-589. Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Quisenberry, D. (2010). Estimating return on leadership development investment. The leadership quarterly, 12, 633644. Bray, N. J. (2008). Proscriptive norms for academic deans: comparing faculty expectations across institutional and disciplinary boundaries. The journal of higher education, 79(6), 692-721 Brungardt, C. (1996). The making of leaders: A review of the literature in leadership development and education. Journal of leadership studies, 3(3), 81-95. California State University Office of the Chancellor. (2011). Explore the system. Retrieved from http://www.calstate.edu/ California State University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Human Resources. (2012). Success stories. Moving forward 2012: Human resources strategic vision and goals, 1-27. California State Budget. (2009). California State Budget 2009-10. Retrieved from http://www.dof.ca.gov/budget/historical/200910/governors/summary/documents/enacted/FullBudgetSummary.pdf Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasiexperimental designs for research. Chicago: Rand McNally. 43 Collins, D. B. & Holton, E. F. (2004). The effectiveness of managerial leadership development programs: a meta-analysis of studies from 1982 to 2001. Human resource development quarterly, 15(2), 217248. Conger, J. A., & Benjamin, B. (1999). Building leaders. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Cook B. & Kim, Y. (2012). The american college president: 2012 edition. American council on education: center for policy analysis. Washington, DC. Dionne, P. (1996). The evaluation of training activities: A complex issue involving different stakes. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 7(3), 279-286. Dlabach, G. (2006). There’s more to leadership than motivation and ability. Academic leader, 22(8), 7 Drew, G. (2010). Issues and challenges in higher education leadership: engaging for change. The Australian educational researcher, 37(3), 5776. El-Ashmawy, A. K. & Weasenforth, D. L. (2010). Internal leadership academy: evaluation of one college’s program. Community college journal of research and practice, 34, 541-560. Fuller, B. J., Hester, K., Barnett, T., Frey, L. & Relyea, C. (2006). Perceived organizational support and perceived external prestige: predicting organizational attachment for university faculty, staff, and administrators. The journal of social psychology, 146(3), 327-347 Gerhart, P. F. & Maxey, C. (1978). College administrators and collective bargaining agreement. Journal of industrial relations, 17(1), 43-52 44 Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press Inc. Hasler, M. G. (2005). Leadership development and organizational culture: which comes first? Academy of human resource management 2005 conference proceedings, Bowling Green, OH: AHRD, 996-1003. Herling, R. W. (2000). Operational definitions of expertise and competence. In R. W. Herling & J. Provo (Eds.), Strategic perspectives of knowledge, competence, and expertise. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Hill, L. A. (2007). Becoming a boss. Harvard business review, January, 2-9 Holton, E. F., III (1996). The flawed four-level evaluation model. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 7(1), 5-21. Jablonski, A. M. (2001). Doctoral studies as professional development of educators in the united states. European journal of teacher education, 24(2), 215-221 Joyce, P. & Cowman, S. (2007). Continuing professional development: investment or expectation? Journal of nursing management, 15, 626633 Kirkpatrick, D. (1959). Techniques for evaluating training programs. Journal of American Society of Training Directors, 13, 3-26. Kirkpatrick, D. (2004). A T+D Classic: how to start an objective evaluation of your training program. T + D, 58(5), 16. Kressel, K., Bailey, J. R., & Forman, S. G. (1999). Psychological consultations in higher education: lessons from a university faculty development center. Journal of educational and psychological consultation, 10(1), 51-82 45 Krohn, R. A. (2000). Training as a strategic investment. In R. W. Herling & J. Provo (Eds.), Strategic perspectives on knowledge, competence, and expertise. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Lamb, T. (2005). The retrospective pretest: an imperfect but useful tool. The evaluation exchange, 9(2), 18. Leskiw, S. L., & Singh, P. (2007). Leadership development: Learning from best practices. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 28(5), 444-464. doi: 10.1108/01437730710761742 Maurer, T. J., Mitchell, D. R. D., & Barbeite, F. G. (2002). Predictors of attitudes toward a 360-degree feedback system and involvement in post-feedback management development activity. Journal of occupational and organizational development, 75, 87-107. McCollum, D. L. & Kajs, L. T. (2009). Examining the relationship between school administrators’ efficacy and goal orientations. Educational research quarterly, 32(2), 29-46 Morgan, G. (2006). Images of organization. Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage Publications Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Hungler, B. P. (2001). Essentials of nursing research: methods, appraisal, and utilization (5th ed). Philidelphia: Lippincott. Reichard, R. J. & Johnson, S. K. (2011). Leader self-development as organizational strategy. The leadership quarterly, 22, 33-42. Scarlett, K. (2012). What is employee engagement? Scarlett surveys international. Retrieved from: http://www.scarlettsurveys.com/papersand-studies/white-papers/what-is-employee-engagement 46 Silver, M., Lochmiller, C. R., Copland, M. A., & Tripps, A. M. (2009). Supporting new school leaders: findings from a university-based leadership coaching program for new administrators. Mentoring and tutoring: partnership in learning, 17(3), 215-232 Smith, D. K. (1991). The impact of leadership behaviors upon job satisfaction productivity and organizational commitment of followers. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Seattle University. Solansky, S. T. (2010). The evaluation of two key leadership development program components: leadership skills assessment and leadership mentoring. The leadership quarterly, 21, 675-681. Sogunro, O. A. (1997). Impact of training on leadership development: Lessons from a leadership training program. Evaluation Review, 21(6), 713-737. Song, W. & Hartley, H. V. (2012). A study of presidents of independent colleges and universities. The council of independent colleges, 1-48. Swanson, R. A., & Holton, E. F. (1999). Results: How to assess performance, learning, and perceptions in organizations. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Taylor, J. & Machado, M. (2006). Higher education leadership and management from conflict to interdependence through strategic planning. Tertiary education and management, 12, 137-160. Torraco, R. J., & Swanson, R. A. (1995). The strategic roles of human resource development. Human Resource Planning, 18(4), 10-21. Webb, K. (2007). Motivating peak performance: leadership behaviors that stimulate employee motivation and performance. Christian higher education, 6, 53-71