Preference is Not Color Blind - Questrom Apps

advertisement

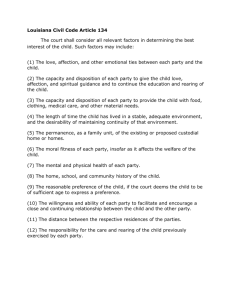

PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 1 Preference is Not Color Blind: Disentangling Implicit Race and Color Effects Ioannis Kareklas Washington State University Robin A. Coulter University of Connecticut Frédéric F. Brunel Boston University Author Note Ioannis Kareklas, Department of Marketing, College of Business, Washington State University. Robin A. Coulter, Marketing Department, School of Business, University of Connecticut. Frédéric F. Brunel, Department of Marketing, School of Management, Boston University. Corresponding author: Ioannis Kareklas, Department of Marketing, College of Business, Washington State University, Todd Addition 375, PO Box 644730, Pullman, WA 99164-4730. E-mail: ioannis.kareklas@wsu.edu PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 2 Abstract This research draws upon theoretical perspectives related to in-group favoritism and color symbolism to hypothesize effects of an individual’s implicit color bias (i.e., preference for the color white vs. the color black) and implicit racial bias (i.e., preference for African American vs. Caucasian racial stimuli) on their implicit reactions to advertisements featuring endorsers of different races. Results from Implicit Association Test (IAT) assessments of participants’ color, racial, and advertising preferences indicate that both African American and Caucasian consumers exhibit an implicit preference for the color white (as compared to the color black), and that implicit color preference significantly influences both their racial preferences and advertising evaluations. These findings document that implicit color bias has a key role in how consumers react to endorsers of their own and other races, thus highlighting the need to remove its effect from evaluations of racial stimuli. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 3 Preference is Not Color Blind: Disentangling Implicit Race and Color Effects The overall propensity to evaluate members of one’s own group more favorably than people belonging to other groups (a.k.a., in-group favoritism) is a generally prevalent and wellestablished social-psychological phenomenon (Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament, 1971). In the consumer domain, one of the direct consequences of in-group favoritism is that consumers are likely to favor ad endorsers whom they perceive to belong to their own in-group over endorsers from other groups. Although this appears to be a robust finding, at least one of the possible bases for in-group identification, race, leads to more varied results. Race (e.g., African American or Caucasian American) is a readily noticeable and salient characteristic of a spokesperson and can serve as a basis for in-group identification and persuasion (Spira & Whittler, 2004; Whittler & Spira, 2002). However, the body of research evidence provides mixed results on the effect of race on persuasion. On one end, research using explicit (i.e., self-report) measures has demonstrated that both African Americans and Caucasian Americans tend to respond more favorably to persuasive messages delivered by endorsers that belong to their own racial in-group (Schlinger & Plummer, 1972; Whittler, 1989; Simpson, Snuggs, Christiansen, & Simples, 2000). Yet, on the other end, psychology and marketing studies utilizing implicit measures have found that although Caucasians tend to exhibit pro-white (in-group) preferences, African Americans tend to not exhibit pro-black (in-group) preferences, and in some instances might even show pro-white preferences (Ashburn-Nardo, Knowles, & Monteith, 2003; Brunel, Tietje, and Greenwald 2004; Nosek, Banaji, & Greenwald, 2002; SmithMcLallen, Johnson, Dovidio, & Pearson, 2006). This lack of automatic preference for one’s ingroup is perplexing, especially in the context of automatic associations which are supposed to be PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 4 free from social-desirability response biases and tap into automatic attitudes and beliefs (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). System justification theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994) has been used to explain the absence of automatic in-group preference for African American respondents. Researchers have proposed that a long history of discrimination can lead minority individuals to internalize negative attitudes toward their own group as a means of justifying the status quo (Rudman, Feinberg, & Fairchild, 2002), and that such attitudes tend to be non-conscious (Jost and Banaji 1994) and can be unearthed by implicit measures (Rudman, Feinberg, & Fairchild, 2002). Although we believe in the merits of system justification theory and the evidence that has been offered in its support, we also believe that there exist at least one other possible explanation for the lack of pro-black automatic in-group preference among African Americans. Instead of offering a historical and sociological discrimination explanation, we propose that there is an even more fundamental explanation for these results. In this research, we argue that individuals’ implicit preferences for the color white versus the color black may impact their evaluations of white versus black faces. We ground our expectations in work on color preference which has shown that in many cultures, the associations for the color white are positive, whereas the color black tends to be associated with more negative connotations (Smith-McLallen et al., 2006). Examples include cultural dress codes that dictate wearing white at weddings and black at funerals (Smith-McLallen et al., 2006), or the portrayal of villains in black hats and good guys in white clothing in traditional American Western films (Frank & Gilovich, 1988). Further, white is often used to connote decency and purity, whereas black is used to connote evil and disgrace (Longshore, 1979). Anthropologists have argued that the preference for the color white over black can be traced to ancient tribal fears PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 5 for darkness, the night and the unknown versus the fondness for white which is linked to light, fire or the sun (Mead & Baldwin, 1971). In general, it has been argued that the preference for white over black is learned from early childhood, is culturally reinforced over time and is a more fundamental automatic preference than race preference (Smith-McLallen et al., 2006). In this article, we seek to extend recent results that showed that for Caucasian respondents an automatic white color preference can be linked to an automatic white racial preference (Smith-McLallen et al., 2006). In particular, we include African Americans in our studies, and use the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998) to investigate how automatic color preference is linked to automatic racial preference at a fundamental level. Furthermore, we explore how automatic color preference is linked to two marketing variables, automatic product preference and automatic spokesperson preference across both racial groups, by varying the color (i.e., black or white) of products, and the race (i.e., African American or Caucasian American) of spokespersons featured in advertisements. In study 1, we show that both African Americans and Caucasian Americans have prowhite automatic color preferences and pro-white-colored product preferences, and that these overall implicit color preferences for the color white can be linked to implicit preferences for white products. In study 2, we replicate the pro-white color preference for both racial groups, but then we show that only Caucasian Americans respondents appear to have automatic racial and advertising spokesperson preferences which are consistent with an in-group favoritism explanation. We also show that for both groups, implicit color preferences are linked to implicit race and advertising spokespersons preferences. We then statistically “remove” the effect of the implicit color preference from the implicit race and advertising spokesperson preference measures and show that once this is done, both racial groups exhibit racial preferences for their PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 6 own in-group. In particular, in contrast to many of the above mentioned studies, the African American respondents have a pro-black racial preference. Thus, we are able to show that automatic color preference and in-group-favoritism are directionally similar and additive in creating automatic racial and Aad preferences for Caucasian Americans. But, for African American respondents, automatic color preference and in-group-favoritism are countervailing forces and therefore allow us to explain why, in ours and many other studies, African American might at first glance appear to lack in in-group favoritism, this being due instead to the fact that as a group (like most other human beings) they prefer the color white over the color black. Theoretical background Implicit racial preference A focal communicator characteristic of interest in persuasion research has been the perceived similarity between the endorsers featured in ads and the targeted consumers. Several studies employing explicit measurement techniques have shown that similar (vs. dissimilar) endorsers are more influential in changing recipient attitudes (Brock, 1965; Woodside & Davenport, 1974). The basis of this effect is in-group favoritism (Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament, 1971), which refers to the propensity to evaluate people who are perceived to belong to your own group more favorably than people belonging to other groups (Spira & Whittler, 2004). Hence, recipients are likely to favor endorsers whom they perceive to belong to their racial ingroup over endorsers who belong to other groups. Racial groups represent pre-defined social categories, hence recipients share socially ascribed group membership with same-race endorsers, and are likely to exhibit in-group favoritism when evaluating ads featuring endorsers of their racial in-group compared to ads featuring out-group endorsers. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 7 Race is a key attribute related to recipients’ perceptions of similarity between themselves and the endorsers featured in advertisements. Given that race is one of the most noticeable physical characteristics (especially in terms of skin color), it is likely to influence persuasion (Spira & Whittler, 2004), and is directly relevant to judgments of similarity. Extant research using explicit measures tends to affirm this assertion. As previously mentioned, several studies have shown that both African American and Caucasian consumers evaluate advertisements featuring same versus different-race endorsers more favorably (e.g., Schlinger & Plummer, 1972; Whittler, 1989). However, studies using explicit measures suffer from response biases when the context is socially sensitive, as in the case of race, because explicit measures allow participants to consciously control their responses (Ashburn-Nardo et al., 2003). Extant studies utilizing implicit measures to examine racial associations have found that both Caucasians and African Americans tend to exhibit implicit pro-Caucasian association bias. For example, Nosek et al. (2002) found that although African Americans exhibited stronger explicit liking for their own racial group than Caucasians, participants of both racial groups exhibited a pro-Caucasian (vs. African American) implicit association bias. Furthermore, research on the neural basis of social group processing has documented that indirect measures of race evaluation, such as the IAT, tend to correlate with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)-assessed activation of the amygdala. The amygdala is a subcortical structure involved in emotional learning and evaluation (Phelps et al., 2000), and is implicated in the automatic evaluation of social stimuli. These results, combined with previous investigations of intergroup attitudes, suggest that implicit negative associations toward a social group may result in an automatic emotional response when encountering members of that group. Lieberman PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 8 et al. (2005, p. 722) posit that the amygdala activity that is “associated with race-related processing may be a reflection of culturally learned negative associations regarding African American individuals.” This explanation is consistent with system justification theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994) which has previously been used to explain why African Americans exhibited a lack of in-group preference in implicit advertising evaluations (Brunel et al., 2004). System justification theory posits that people are motivated to believe in a just world, and that a history of discrimination can lead minority individuals to internalize negative attitudes toward their own group as a means of justifying the status quo (Rudman, Feinberg, & Fairchild, 2002). Jost and Banaji (1994) emphasize that such attitudes and the motive to sustain them are likely to be non-conscious. This explains why this phenomenon may not be picked up by selfreport measures, but can be unearthed by implicit measures (Rudman, Feinberg, & Fairchild, 2002) which assess automatic associations that are believed to underlie nonconscious attitudes and beliefs (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). To summarize, extant research using implicit measures demonstrates a preference for Caucasian racial stimuli for both African Americans and Caucasians. Implicit color preference Researchers in psychology have theorized about an individual’s color bias; that is, an implicit color preference for some colors over others (Smith-McLallen et al., 2006). Two theories have been advanced to explain the development of color preference in young children. The majority of researchers in this area believe that the emergence of color preference in young children is due to the cultural socialization of color symbolism. This theory suggests that children develop a pro-white/anti-black color preference through the verbal learning of color symbolism in their culture (Duckitt, Wall, & Pokroy, 1999). In other words, as a child’s verbal PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 9 comprehension develops, s/he learns to associate the color white with positive connotations and the color black with negative connotations. Williams, Tucker, and Dunham (1971) note that the color white has been used in religion, literature, and the mass media as a symbol of “goodness,” whereas the color black has been used as a symbol of “badness.” For example, the English language idiom black sheep is a derogatory term (because black wool is less valuable than white wool) used to describe an undesirable or disreputable member of a group. In contrast, the term white knight is used in the management literature to describe a friendly company that is invited by the target management to outbid an unwanted bidder, and thus protect the company from a hostile takeover (Jensen & Ruback, 1983). Frank and Gilovich (1988) observed that the terms “Black Thursday” (referring to Thursday, Oct 24, 1929 when stock values dropped leading to the Great Depression of the 1930’s), being “blacklisted” or “blackmailed” all carry negative connotations. Other researchers favor the early experience theory proposed by Williams and Morland (1976) as an explanation for the emergence of a pro-white/anti-black color preference in children. Early experience theory proposes that young children develop a preference for the color white as compared to the color black as a result of their early experiences with light and darkness. Specifically, as diurnal beings, we require light to interact effectively with our environment, and may find darkness to be disorienting and therefore intrinsically aversive (Williams, Boswell, & Best, 1975). Early experience theory suggests that a child’s early experiences with the light of day and the darkness of the night lead her/him to develop a preference for light over darkness, which may then generalize to a preference for the color white as compared to the color black (Williams et al. 1975). PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 10 As noted, cross-cultural research indicates a prevalence of positive associations with the color white and negative associations with the color black (Adams & Osgood, 1973). Several studies have documented the existence of a pro-white/anti-black color preference using participants from varying social and ethnic backgrounds, indicating that this may be a pancultural phenomenon. For example, Adams and Osgood, (1973) used semantic differential scales to study the color preferences of adults and found that participants evaluated the color white more positively than the color black. Others have used an indirect measure called the Color Meaning Test (CMT II; Williams et al., 1975) to study color preference in children. Researchers using the CMT II have found support for a pro-white/anti-black color preference in children from varying cultures including: European-American (Boswell & Williams, 1975), African American (Williams & Rousseau, 1971), and bi-racial American (Neto & Paiva, 1998). Furthermore, a cross-cultural study investigating the affective meanings of color in 23 cultures found that the color black is viewed as the color of evil and death in almost all cultures (Adams & Osgood, 1973). Hence, we expect that: H1: Caucasian and African American participants will exhibit an implicit color preference for the color white as compared to the color black. Relationship between color preference and product preference Color is an important component of marketing communications, and its effects have been widely studied in the areas of advertising, packaging, and store design (Bellizzi, Crowley, & Hasty, 1983). While a large portion of color research on products by marketers has not been published due to competitive concerns (Bellizzi et al., 1983), extant published research has shown that effective use of color can attract attention (Lee & Barnes, 1989), and influence consumers’ perceptions and behaviors (Aslam, 2006). PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 11 Consumers deliberately choose product colors that complement their desired self-image (Madden et al., 2000). For example, consumers choose colors for their houses, cars, and clothes that are consistent with how they want to present themselves (Trinkaus, 1991). We anticipate that consumers’ implicit product preferences will be consistent with their implicit color preferences. As noted in the previous section, extant research suggests that consumers from varying backgrounds have a non-conscious preference for the color white over the color black. Hence, we expect that: H2: Caucasian and African American participants will exhibit an implicit product preference for white as compared to black colored products. H3: Implicit color preference will predict implicit product preference, such that participants who implicitly prefer the color white (black) will also tend to implicitly prefer white (black) colored products. Relationship between color preference and racial preference Research suggests that individuals develop a preference for the color white over the color black at an early age, and this contributes to the later development of racial preference (Duckitt, Wall, & Pokroy, 1999). Correlational studies have found a significant positive relationship between color and racial preferences, such that participants with a high degree of pro-white/antiblack color preference tend to evaluate dark-skinned people less favorably than light-skinned people (Williams, 1969; Boswell & Williams, 1975; Neto & Williams, 1997). Livingston and Brewer (2002) found that Caucasian participants made more negative associations with African Americans than Caucasians, especially for African Americans with prototypic features such as darker colored skin. Similarly, Maddox and Gray (2002) report that both Caucasian and African American participants exhibited stronger associations between stereotypic negative racial PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 12 characteristics (e.g., being criminal, poor, or aggressive) and darker-skinned African Americans. Furthermore, experimental studies show evidence for a functional relationship between color and racial preferences (Williams et al., 1975). For example, Williams and Edwards (1969) used reinforcement procedures to weaken participants’ pro-white/anti-black color preferences, which subsequently led to a reduction in their pro-Caucasian/anti-Black racial evaluations, and later studies replicated these findings in different cultures and societies (Duckitt et al., 1999). The aforementioned theory and research findings suggest that participants’ implicit color preferences will influence their implicit racial preferences and their implicit evaluations of advertisements that feature African American or Caucasian endorsers. Hence, we expect: H4: Implicit color preference will predict implicit racial preference and implicit advertising preference, such that participants who implicitly prefer the color white (black) will also tend to implicitly prefer Caucasian (African American) faces and advertisements featuring Caucasian (vs. African American) endorsers. H5: Implicit racial preference will mediate the effect of implicit color preference on participants’ implicit advertising preference. Disentangling color preference from racial and advertising evaluations. As previously mentioned, studies using implicit measurement techniques such as the IAT generally find that both Caucasian and African American participants exhibit pro-Caucasian association bias when responding to racial stimuli (Nosek et al., 2002). This finding is incongruent with the vast majority of extant studies assessing participants’ advertising preferences in response to ads featuring in-group versus out-group models. We expect that the influence of color preference on racial evaluations may partially account for this disparity. Specifically, we disentangle the effect PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 13 of participants’ implicit color preferences from their implicit racial and implicit advertising preferences, and test the following hypothesis: H6: After controlling for color preference, both African American and Caucasian participants will exhibit implicit racial and advertising preferences in favor of their racial in-group. Methodology Recent research in consumer behavior and psychology has acknowledged that consumption behavior is frequently affected by cognitive processes outside conscious awareness and control (Bargh, 2002; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Moreover, even when research participants are aware of their attitudes, they may be unwilling to share them or may purposefully distort their answers to avoid embarrassment, especially when the topic of interest is socially sensitive in nature (Mick, 1996). Methodological advances in implicit measurement techniques have enabled researchers to use indirect measures to examine participants’ racial associations. Implicit measures provide an indirect estimate of the construct of interest, without directly asking the participant (Fazio & Olson, 2003). Prominent examples include projective techniques (Haire, 1950), various forms of priming (Fazio, Sanbonmatsu, Powell, & Kardes, 1986), the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998), and the Go/No-Go Association Task (Nosek & Banaji, 2001). In our research, we employ the IAT, a well-established and widely used technique for measuring implicit associations (Fazio & Olson, 2003), to explore whether both African American and Caucasian respondents exhibit an implicit color preference (ICP) for the color white as compared to the color black, and an implicit product preference (IPP) for white products as compared to black products. Furthermore, we examine whether participants’ implicit racial PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 14 preference (IRP) may be partially explained by their implicit color preference (ICP). In addition, we investigate the effect of these two antecedents of attitude toward the ad (i.e., IRP and ICP) on participants’ implicit attitudes toward advertisements (IAad) featuring African American and Caucasian endorsers. Study 1 Study 1 was designed to test the first three hypotheses. While extant research has shown that Caucasian participants exhibit an implicit color preference for the color white as compared to the color black (Smith-McLallen et al., 2006) replicating past studies using explicit measures, to the best of our knowledge, no other study has examined the color preferences of African American respondents using an implicit measure. Furthermore, we designed study 1 to test whether participants’ automatic color preferences are related to their automatic preference for white versus black colored products. Participants, Materials and Procedure We recruited Caucasian and African American participants from an online panel provider to participate in an IAT experiment. Following the recommendations of Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (2003), individual trial response latencies greater than 10,000 milliseconds, and data from participants who responded faster than 300 milliseconds on more than 10% of trials were eliminated. This yielded a total of 219 useable responses from 123 Caucasian (64 female and 59 male) and 96 African American (77 female and 19 male) respondents, with a mean age of 39 years old. Participants completed two separate IAT procedures: a color IAT, and a product IAT. Each IAT consisted of seven blocks. Blocks four and seven (counterbalanced) were the PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 15 measurement blocks. Within each of the three IAT tasks, the order in which participants encountered the black preference blocks (pairing black stimuli with pleasant words, and white stimuli with unpleasant words) and white preference blocks (pairing white stimuli with pleasant words, and black stimuli with unpleasant words) was counterbalanced. Categorization labels (e.g., “Pleasant vs. Unpleasant”) appeared on the top right and the top left of the computer screen, and a randomly selected stimulus (either an image or a word) from that IAT appeared in the middle of the screen. Participants were instructed to sort stimuli to the appropriate category as quickly as they could, while trying to minimize errors. Participants were instructed to press the “D” key on their computer keyboard if the correct category label for the target stimulus appeared on the left side of the screen, and the “K” key if the appropriate category label appeared on the right side of the screen. Whenever participants responded correctly, the next stimulus and category labels appeared; whenever participants’ responses were incorrect, a red “X” appeared and remained on the screen until the stimulus was correctly classified. Stimuli development. All IAT stimuli used a gray background (RGB color code 127 127 127), which is exactly between the colors black and white in the color spectrum to avoid priming participants with either the color white or black. Additionally, we set the background color of all experimental procedures to the same color gray. The color IAT assessed participants’ implicit color preferences for the colors white and black, using pictures of black and white geometric shapes as color stimuli (see the Appendix for examples of the stimuli used in each IAT), and words with positive (e.g., “happiness”) and negative (e.g., “misery”) connotations as evaluative stimuli to represent the two attribute concepts (i.e., Pleasant and Unpleasant). The product IAT Measurement of IAT effects. As IAT studies are based on latency measures, participants’ response latencies were recorded (in milliseconds) from the onset of each stimulus PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 16 to its correct classification for the two measured blocks in each IAT. Mean preference scores were calculated using the improved D score algorithm (Greenwald et al., 2003). Specifically, D was scored so that higher numbers indicate a stronger association between pleasant words and Caucasian stimuli on the race IAT and advertising IAT, and white shapes on the color IAT. Therefore, a positive (negative) D implies that participants paired Caucasian (or white) stimuli with pleasant words and African American (or black) stimuli with unpleasant words quicker (slower) than they paired African American (or black) stimuli with pleasant words and Caucasian (or white) stimuli with unpleasant words. In contrast to the earlier conventional scoring procedure, the improved algorithm minimizes the effect of having previously completed one or more IATs on the calculated IAT scores (Greenwald et al., 2003), which is particularly important for the present experiment where participants were asked to complete three separate IAT procedures. Results Our findings for study 1, the mean D scores, 95% confidence intervals, and correlations for the two IAT tasks are presented in Table 1. In support of hypothesis 1, both Caucasians (ICP Mean d = .68, t(122) = 18.48, p <.001) and African Americans (ICP Mean d = .23, t(95) = 4.17, p <.001) exhibited an implicit preference for the color white as compared to the color black in the color IAT. In support of hypothesis 2, we found that both Caucasians (IPP Mean d = .48, t(122) = 15.05, p <.001) and African Americans (IPP Mean d = .17, t(95) = 4.23, p <.001) exhibited an implicit preference for white as compared to black colored products in the product IAT. To test the relationship between participants’ implicit color preferences and implicit product preferences, we performed a regression predicting the product IAT scores from the color IAT scores. We found that both Caucasians’ (β = .28, p < .01) and African Americans’ (β = .43, PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 17 p < .01) implicit color preferences significantly predicted their implicit product preferences in support of hypothesis 3. In other words, participants who implicitly preferred the color white (black) also tended to implicitly prefer white (black) colored products. –––––––––––––––––––– Insert Table 1 about here –––––––––––––––––––– Study 2 The results of study 1 showed that both African American and Caucasian respondents exhibited an implicit preference for the color white, which was significantly related to their implicit preference for white colored products. Study 2 was designed to test hypotheses four, five, and six. Specifically, we designed study 2 to test whether participants’ color preferences predict their implicit racial and implicit advertising preferences. More importantly, we test whether removing the effect of color preference from racial and advertising evaluations can yield responses in favor of respondents’ in-group as documented by many extant studies utilizing explicit measures. The results of study 1 suggest that both African Americans and Caucasians prefer the color white over the color black. Hence, we expect that controlling for the effect of color preference should decrease (increase) Caucasian (African American) participants’ implicit racial and implicit advertising preferences in favor of their racial in-group as described in H6. Participants, Materials and Procedure We recruited from 245 Caucasian (122 female and 123 male) and 81 African American (49 female and 32 male) undergraduate students, with a mean age of 22 years old to participate in an IAT experiment. Participants completed three separate IAT procedures: a color IAT, a race PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 18 IAT, and an advertising IAT. All IAT procedures and the measurement of IAT effects were identical to study 1. Stimuli development. We used the same color IAT as in study 1. The race IAT assessed participants’ implicit racial preferences using six pictures of African American faces and six Caucasian faces as race stimuli. An equal number of female and male models of each race, photographed in similar poses were used. The advertising IAT assessed overall preference for advertisements featuring either an African American or a Caucasian athlete as an endorser. Twelve ads were used, six depicting African American endorsers, and six depicting Caucasian endorsers in similar poses. The ads as stimuli in the advertising IAT were previously used by Brunel et al. (2004, study 2), with the only exception that we added a gray background (RGB color code 127 127 127) to all stimuli. Great care was taken to have an equal representation of the two featured brands (Etonic and New Balance), and to display each brand name colored either black or white an equal number of times to ensure that participants were not systematically exposed to a greater number of white or black colored stimuli. Results Our findings for study 2 for the three IAT tasks are presented in Table 2. In support of hypothesis 1, and replicating the results of study 1, both Caucasians (ICP Mean d = .58, t(244) = 21.79, p <.001) and African Americans (ICP Mean d = .36, t(80) = 6.81, p <.001) exhibited an implicit preference for the color white as compared to the color black in the color IAT. We also found that Caucasians exhibited an implicit in-group racial preference in the race IAT (IRP Mean d = .46, t (244) = 20.60, p <.001), whereas African Americans did not exhibit a significant implicit racial preference (IRP Mean d = -.02, t(80) = -.44, p = .66). Similarly, and consistent with Brunel et al. (2004), Caucasians exhibited an implicit in-group advertising preference in the PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 19 advertising IAT, favoring advertisements featuring Caucasian (vs. African American) endorsers (IAad Mean d = .40, t(244) = 17.59, p <.001), whereas African Americans did not exhibit a significant implicit advertising preference (IAad Mean d = -.03, t (80) = -.72, p = .47). –––––––––––––––––––– Insert Table 2 about here –––––––––––––––––––– To test the relationship between participants’ color preferences and racial preferences, we performed a regression predicting the race IAT scores from the color IAT scores. We found that both Caucasians’ (β = .35, p < .001) and African Americans’ (β = .23, p < .05) implicit color preferences significantly predicted their implicit racial preferences in support of hypothesis 4. Similarly, to test the relationship between participants’ color and advertising preferences we regressed participants’ advertising IAT preference scores on their color IAT preference scores. Once again, the regression results lend support to hypothesis 4 as both Caucasians’ (β = .21, p < .01) and African Americans’ (β = .29, p < .01) implicit color preferences significantly predicted their implicit advertising preferences. We also regressed participants’ advertising IAT scores on their racial IAT scores and found that both Caucasians’ (β = .47, p < .001) and African Americans’ (β = .41, p < .001) implicit racial preferences significantly predicted their implicit advertising preferences. Hypothesis 5 suggests that IRP will mediate the effect of ICP on IAad. Consistent with this hypothesis, both Caucasian (Sobel test statistic = 5.32; p < .001) and African American (Sobel test statistic = 2.19; p < .01) participants’ implicit racial preferences mediated the effect of their implicit color preferences on their implicit advertising preferences. To evaluate our final hypothesis, we need to disentangle the effect of ICP on participants’ IRP and IAad. To control for the effect of ICP on IRP, we used a generalized linear model (GLIM) formulation to estimate equation 1 parameters, which allows for potential correlation PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 20 between ICP and IRP from the same participant through the error term ε1i. The Pearson residual (ε1i), represents Unique Implicit Racial Preference (UIRP), as it equals to IRP as calculated by the race IAT with the effect of ICP as calculated by the color IAT removed. To control for the effect of ICP on IAad, we used equation 2 to obtain the Pearson residual (ε2i), which represents Unique Implicit Attitude toward the Ad (UIAad), as it equals to IAad as calculated by the advertising IAT with the effect of ICP as calculated by the color IAT removed. IRPi = a + b x ICPi + ε1i IAadi = a + b x ICPi + c x έ1i + ε2i (1) (2) The resulting UIRP and UIAad for Caucasian and African American participants are presented in Table 2. In support of hypothesis 6, after removing the effect of color preference from participants’ race IAT preference scores we find that both Caucasian (UIRP Mean d = .10, t(244) = 4.79, p <.001) and African American (UIRP Mean d = -.30, t(80) = -6.88, p <.001) participants exhibit a unique implicit racial preference in favor of their racial in-group. Similarly, after controlling for ICP we find that both Caucasian (UIAad Mean d = .09, t(244) = 4.11, p <.001) and African American (UIAad Mean d = -.28, t(80) = -7.42, p <.001) participants exhibit a unique implicit advertising preference for ads depicting endorsers of their racial in-group. In other words, after controlling for participants’ preference for the color white, Caucasians’ racial and advertising preferences for Caucasian models decreased, while African Americans’ racial and advertising preferences for African American models increased, and reached significant levels. Furthermore, after removing the effect of implicit color preference from participants’ implicit racial and implicit advertising preferences, UIRP and UIAad are significantly correlated for both African American (r = .38, p <.01) and Caucasian participants (r = .43, p <.01). PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 21 Discussion Our research draws much needed attention to consumers’ underlying associations related to race and color, and contributes to our understanding of their respective individual and joint effects on consumers’ evaluations of advertisements featuring African American and Caucasian endorsers. Our experiment is the first to consider consumers’ implicit color preferences in the context of their advertising preferences for endorsers of different races. We find that both African American and Caucasian participants exhibit an implicit preference for the color white (as compared to the color black). This finding is consistent with the extant literature as several studies have documented the existence of a pro-white color preference using both adults and children from varying social and ethnic backgrounds (Adams & Osgood, 1973; Boswell & Williams, 1975; Neto & Williams, 1997). Extant research suggests that the cultural socialization of color symbolism has a pervasive influence on individuals’ development of racial preferences, which in turn may affect individuals’ evaluations of advertisements featuring endorsers of different races. As expected, we document that both Caucasian and African American participants’ pro-white color preference contributed significantly to their racial and advertising preferences, suggesting the need to remove the effect of color preference from all evaluations of racial stimuli. Theoretical work related to in-group favoritism (Tajfel et al., 1971) suggests that African Americans (Caucasians) should prefer African American (Caucasian) endorsers when racial groups are explicitly mentioned. However, extant studies using implicit measures such as the IAT generally report that both Caucasian and African American participants tend to exhibit implicit pro-Caucasian association bias when exposed to racial stimuli. Our results suggest that a PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 22 potential reason for such a disparity is the biasing effect of participants’ pro-white implicit color preference on implicit measures of racial evaluations. While there is a rich body of research examining African American and Caucasian consumers’ advertising reactions to different race endorsers (Schlinger & Plummer, 1972; Szybillo & Jacoby, 1974; Whittler & Spira, 2002), almost all extant studies have relied on explicit measures. In addition to our present experiment, the only other study we are aware of that has used an implicit measure to assess participants’ advertising reactions to Caucasian and African American endorsers is Brunel et al. (2004; study 2). Our findings, which are based on IAT responses from 81 African Americans, replicate those of Brunel et al.’s (2004) study, with IAT responses from 6 African Americans. Both studies found a lack of a significant implicit preference in the advertising IAT among African American participants, and a pro-Caucasian advertising preference among Caucasian participants. This result may be attributed to the fact that mass media advertisements have traditionally featured Caucasian endorsers, at the exclusion of African Americans and other racial and ethnic groups. Importantly however, after controlling for the effect of implicit color preference, participants of both races exhibited a significant preference for in-group racial stimuli, both in their race and in their advertising evaluations. Thus in summary, our results point to the implicit preference for the color white as a key explanatory variable that has favorably exaggerated the in-group advertising preferences of Caucasians, while attenuating those of African Americans. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 23 References Adams, F. M., & Osgood, C. E. (1973). A cross-cultural study of the affective meanings of color. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 4(2), 135-156. Ashburn-Nardo, L., Knowles, M. L., & Monteith, M. J. (2003). Black Americans' implicit racial associations and their implications for intergroup judgment. Social Cognition, 21(1), 61-87. Aslam, M. M. (2006). Are you selling the right colour? A cross-cultural review of colour as a marketing cue. Journal of Marketing Communications, 12(1), 15-30. Bargh, J. A. (2002). Losing consciousness: Automatic influences on consumer judgment, behavior, and motivation. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(2), 280-285. Bellizzi, J. A., Crowley, A. E., & Hasty, R. W. (1983). The effects of color in store design. Journal of Retailing, 59(1), 21-45. Boswell, D. A., & Williams, J. E. (1975). Correlates of race and color bias among preschool children. Psychological Reports, 36(1), 147-154. Brock, T. C. (1965). Communicator-recipient similarity and decision change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1(6), 650-654. Brunel, F. F., Tietje, B. C., & Greenwald, A. G. (2004). Is the Implicit Association Test a valid and valuable measure of implicit consumer social cognition? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(4), 385-404. Duckitt, J., Wall, C., & Pokroy, B. (1999). Color bias and racial preference in White South African preschool children. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 160(2), 143-154. Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and uses. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 297-327. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 24 Fazio, R. H., Sanbonmatsu, D. M., Powell, M. C., & Kardes, F. R. (1986). On the automatic activation of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(2), 229-238. Frank, M. G., & Gilovich, T. (1988). The dark side of self- and social perception: Black uniforms and aggression in professional sports. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 74-85. Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4-27. Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480. Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197-216. Haire, M. (1950). Projective techniques in marketing research. Journal of Marketing, 14(5), 649656. Jensen, M. C., & Ruback, R. S. (1983). The market for corporate control: The scientific evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 11(1-4), 5-50. Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33(1), 1-27. Lee, S., & Barnes, J. H. (1989). Using color preferences in magazine advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 29(6), 25-30. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 25 Lieberman, M. D., Hariri, A., Jarcho, J. M., Eisenberger, N. I., & Bookheimer, S. Y. (2005). An fMRI investigation of race-related amygdala activity in African-American and CaucasianAmerican individuals. Nature Neuroscience, 8(6), 720-722. Livingston, R. W., & Brewer, M. B. (2002). What are we really priming? Cue-based versus category-based processing of facial stimuli. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 5-18. Longshore, D. (1979). Color Connotations and Racial Attitudes. Journal of Black Studies, 10(2), 183-197. Madden, T. J., Hewett, K., & Roth, M. S. (2000). Managing images in different cultures: A cross-national study of color meanings and preferences. Journal of International Marketing, 8(4), 90-107. Maddox, K. B., & Gray, S. A. (2002). Cognitive representations of Black Americans: Reexploring the role of skin tone. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(2), 250259. Mead, M., & Baldwin, J. (1971). A rap on race. New York: J.B. Lippincott. Mick, D. G. (1996). Are studies of dark side variables confounded by socially desirable responding? The case of materialism. Journal of Consumer Research, 23(2), 106-119. Neto, F., & Paiva, L. (1998). Color and racial attitudes in White, Black and biracial children. Social Behavior and Personality, 26(3), 233-244. Neto, F., & Williams, J. E. (1997). Color bias in children revisited: Findings from Portugal. Social Behavior and Personality, 25(2), 115-122. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 26 Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration web site. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6(1), 101-115. Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2001). Privately expressed attitudes mediate the relationship between public and implicit attitudes. Paper presented at the Society of Personality and Social Psychology, San Antonio. Phelps, E. A., O'Connor, K. J., Cunningham, W. A., Funayama, E. S., Gatenby, J. C., Gore, J. C., & Banaji, M. R. (2000). Performance on indirect measures of race evaluation predicts amygdala activation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12(5), 729-738. Rudman, L. A., Feinberg, J., & Fairchild, K. (2002). Minority members' implicit attitudes: Automatic ingroup bias as a function of group status. Social Cognition, 20(4), 294-320. Schlinger, M. J., & Plummer, J. T. (1972). Advertising in black and white. Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 9(2), 149-153. Simpson, E. M., Snuggs, T., Christiansen, T., & Simples, K. E. (2000). Race, Homophily, and Purchase Intentions and the Black Consumer. Psychology & Marketing, 17(10), 877-889. Smith-McLallen, A., Johnson, B. T., Dovidio, J. F., & Pearson, A. R. (2006). Black and white: The role of color bias in implicit race bias. Social Cognition, 24(1), 46-73. Spira, J. S., & Whittler, T. E. (2004). Style or substance? Viewers' reactions to spokesperson's race in advertising. In J. D. Williams, W.-N. Lee & C. P. Haugtvedt (Eds.), Diversity in advertising: Broadening the scope of research directions. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum. Szybillo, G. J., & Jacoby, J. (1974). Effects of different levels of integration on advertising preference and intention to purchase. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(3), 274-280. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 27 Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149-178. Trinkaus, J. (1991). Color preference in sport shoes: An informal look. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 73(2), 613-614. Whittler, T. E. (1989). Viewers' processing of actor's race and message claims in advertising stimuli. Psychology & Marketing, 6(4), 287-309. Whittler, T. E., & Spira, J. S. (2002). Model's race: A peripheral cue in advertising messages? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(4), 291-301. Williams, J. E. (1969). Individual differences in color-name connotations as related to measures of racial attitude. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 29(2), 383-386. Williams, J. E., Boswell, D. A., & Best, D. L. (1975). Evaluative responses of preschool children to the colors white and black. Child Development, 46(2), 501-508. Williams, J. E., & Edwards, D. C. (1969). An exploratory study of the modification of color and racial concept attitudes in preschool children. Child Development, 40(3), 737. Williams, J. E., & Morland, J. K. (1976). Race, color, and the young child. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Williams, J. E., & Rousseau, C. A. (1971). Evaluation and identification responses of negro preschoolers to the colors black and white. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 33(2), 587-599. Williams, J. E., Tucker, R. D., & Dunham, F. Y. (1971). Changes in the connotations of color names among negroes and caucasians: 1963-1969. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 19(2), 222-228. Woodside, A. G., & Davenport, J. W. J. (1974). The effect of salesman similarity and expertise on consumer purchasing behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 11(2), 198-202. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 28 Table 1 Means, confidence intervals, and correlations for IAT tasks in study 1. Caucasians (N = 123) African Americans (N = 96) Correlations IAT Task ICP1 IPP2 Mean D 95% CI .68*** .48*** .61, .76 .42, .54 ICP .28** IPP Correlations Mean D 95% CI ICP .23*** .17*** .12, .34 .09, .24 .43** IPP Note: CI = confidence interval; ICP = Implicit Color Preference; IPP = Implicit Product Preference. Positive (negative) mean D scores indicate an implicit color preference for white (black) geometric shapes. 2 Positive (negative) mean D scores indicate an implicit product preference for white (black) colored products. ** p <.01. *** p <.001. 1 PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 29 Table 2 Means, confidence intervals, and correlations for IAT tasks in study 2. Caucasians (N = 245) African Americans (N = 81) Correlations IAT Task Mean D 95% CI ICP1 IRP2 IAad3 UIRP2 UIAad3 .58*** .46*** .40*** .10*** .09*** .53, .64 .42, .50 .36, .44 .06, .14 .05, .14 ICP .35** .21** -.07 -.11 IRP .47** .91** .36** IAad .41** .95** Correlations UIRP Mean D 95% CI ICP IRP IAad UIRP .43** .36*** -.02 -.03 -.30*** -.28*** .26, .47 -.11, .07 -.11, .05 -.39, -.22 -.35, -.20 .23* .29** -.20 -.09 .41** .91** .34** .29** .93** .38** Note: CI = confidence interval; ICP = Implicit Color Preference; IRP = Implicit Racial Preference; IAad = Implicit Attitude toward the Ad; UIRP = Unique Implicit Racial Preference; UIAad = Unique Implicit Attitude toward the Ad. 1 Positive (negative) mean D scores indicate an implicit color preference for white (black) geometric shapes. 2 Positive (negative) mean D scores indicate an implicit racial preference for images of Caucasian (African American) individuals. 3 Positive (negative) mean D scores indicate an implicit advertisement preference for Caucasian (African American) endorsers. * p <.05. ** p <.01. *** p <.001. PREFERENCE IS NOT COLOR BLIND 30 Appendix Examples of IAT stimuli used in studies 1 and 2 Color IAT (Studies 1 and 2) Race IAT1 (Studies 1 and 2) Product IAT (Study 1) Advertising IAT1 (Study 2) Note: All stimuli were presented at a resolution of approximately 250 x 250 pixels, and the background color was gray (RGB color code 127 127 127). 1 An equal number of women and men from each racial group photographed in similar poses were depicted in both the race and advertising IATs.