Ethnography Final Draft

advertisement

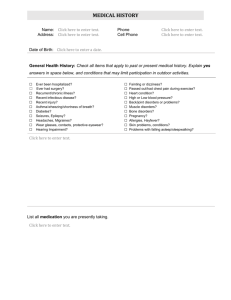

Harris 1 Sam Harris Dr. Walls ENC 1102H 22 April 2014 I Got Myself Here, but Get Me Out of Here!: An Ethnography of a Hospital Floor One of the two doctors on shift on the fourth floor of the Halifax Hospital in Port Orange, Florida, was a petite, blonde, Caucasian woman in her late twenties/early thirties. She walked through the long, narrow, well lit, hallways of the fourth floor with an eager to learn pre-med student in a lab coat behind her, carrying an iPad, taking notes on everything he saw as fast as he could. They had already seen eight patients together that today, but there was still two more left to check up on before the young man had to depart back to his gated community apartment in Orlando, Fl. Prior to entering the ninth patients room the doctor read over the patient’s records and notes, she has all the information of the patients she is seeing today folded up in to three pieces of paper stapled together in her pocket. This paper was printed for her at the beginning of the day, same as every other day. The paper that she referenced informed her that Patient 9 is a woman with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), a common reason for hospitalization, directly related to long term usage of cigarettes. When the Doctor and Observer entered the room, the observer noticed that the patient had her phone lying next to her head on the bed, the phone was producing classical music. She had her eyes closed, looking serene and peaceful as she lay on her back. As they approached closer, the patient paused her music and greeted them. Harris 2 The very first thing the patient asked was how much longer she would need to be hooked in to the IV’s in her arm. The doctor informed her that it would be at least one more day, and she responded with a frown and a sigh, expressing her discomfort and disappointment.. The patient absorbed this and agreed as the conversation segued in to how grateful the patient was for the view of the window, which overlooked a man made lake, many green trees covered in moss, and some parking lot. Following a short conversation about the view, the doctor and observer left the patient, and she resumed her classical music. The doctor repeated the process of checking her “cheat sheet” before entering the tenth patient’s room. It informed her that the patient was a woman with congestive heart failure. The patient was told of her condition being a combination of “congestive heart failure and pneumonia” to which she smiled, laughed, and responded, “Oh great, a double whammy.” Immediately following this diagnostic she asked when she would be able to leave, the doctor informed her that she would possibly be able to leave tomorrow. The patient expressed happiness on her face, and coincidentally also mentioned how she was grateful for the view out the window (Patient 9 and 10 had rooms directly next to each other so they had the same view). She explained that her and her husband were here for the winter and that he was visiting her earlier but the hospital is no place to be when it is so nice outside and she told him to come back after dinner. This personal story of these two patients accurately depicts the overlying claim, and a couple of the sub claims that I intend to make about the discourse of a hospital based on my observational research of the Fourth floor of Halifax Hospital. I spent over Harris 3 five hours there taking note of social interactions involving technology, texts, and people. The purpose was to identify patterns of actions that categorize a hospital floor discourse in of itself. After research I found that I wanted my research question to specifically only focus on the patients as my subject, and exclude the observed actions of the hospital staff. I use Gee’s interpretation of discourse in What is Literacy? to define a discourse as an “identity kit”; actions or language that identify you as fitting in to a particular group (1). “This “identity kit” is the exact ability to interpret a new situation and act accordingly.” (Harris 1). In order to identify this common “identity kit” among patients I focused specifically on what patients said to the Doctors and Nurses, how they conducted themselves through actions, and how they utilized texts and technologies. My thesis is that patients are almost without exception eager to leave the hospital. The proportion of patients that asked when they would be able to leave during the doctor’s check up on them is the first observation that supports this thesis. Within the conversations between the doctor and the patient when she was checking up on him or her, almost every single patient asked (or it came up somehow) when he or she would be able to leave. An affirmative answer to any of these questions was met without exception with a smile. The negative answer to these questions was met with sighs and frowns. One patient actually sent her husband home because she told him that, “It is too nice of a day outside to spend in the hospital.” Logically it makes sense, these people have lives outside of the hospital, one patient desired to leave because he wanted to take care of his mom, and another because she didn’t want to have to leave her kids with her husband any longer. After an extensive research study done on self discharge against medical advice it was speculated that one aspect of the unspoken code Harris 4 between doctors and patients is that, “the hospitalization is aimed at the betterment of the patient’s health, which I more important than the business that the patient might need to attend to outside the hospital.” (Ibrahim, Kent Kwoh, and Krishnan 2207). Both patient and doctor understand this unspoken code. Although getting healthy is the more important objective, observation would support that it does not prevent patients from wanting to leave. A major factor that seemed to contribute to patients wanting to leave the hospital is that patients seemed to be very uncomfortable with their situation. Other than asking when they could leave, other questions expressing discomfort were asked such as two patients asked when they would be able to eat solid food, and a third patient asked when she would be able to get her IV’s out. There was a patient who was repeatedly yelling from pain, expressing her discomfort. One great example of a patient being uncomfortable is she was quoted saying, “don’t come to the hospital if you are trying to sleep.” Just the sheer number of patients who requested pain medication is an accurate representation of their discomfort. The problem of discomfort in the hospital is clearly understood by both patient and doctor, because there is a pain scale on the wall that the doctor updates upon checking up on the patients Figure 1: Pain Scale (see figure 1). Another aspect of the unspoken code between doctors and patients in a hospital mentioned by Ibrahim, Kent Kwoh, and Krishnan is, “The patient will stay in the hospital as long as Harris 5 necessary, but no longer” (2207). This understanding is due to the level of discomfort that is common among almost all patients in the hospital. Another behavior that categorizes the “identity kit” of someone in the hospital is an attempt to escape from the present moment by distracting themselves with text and technology. Within my observations I saw patients spending time doing everything from reading cosmopolitan magazine, to playing trance like iPhone games, to listening to classical music from their phone, to staring at Spanish moss out of their window. It was a strange coincidence that two patients in rooms next to each other both noted that they were using the beautiful view out of their window as a visual escape (see figure 2). The books that the patients Figure 2: View from Window had in their possession ranged from James Patterson, to The New Rules of Marketing and PR. I did not observe a pattern in the type of texts that the patients were using to distract themselves, because everyone had different interests when it came to literature. I don’t think there was an observable pattern present within the type of text, although the fact that over half of the patients had some sort of technology or text that they were actively using is an observable pattern within itself. One patient in reference to his iPhone game said that it was what was, “getting him through”. Even with patients that did not have their own technology or text present, almost every single one had the television on, and Harris 6 one patient in particular was very invested in her unknown soap opera that was on her television. To further this observation I think that the presence of technology and texts as a distraction represents the fact that the patients do not want to face the reality that they are very sick, and some of them facing death. This use of text and technology as a distraction further supports the thesis that patients desperately want to leave the hospital. By distracting themselves with books, games, shows, movies, music, etc. they can occupy their brains from thinking of the one thing that they desperately want; which is freedom. Another pattern of observations that I made is that patients and relatives of patients have more patience with the doctors than the nurses. For me, this translates in to a claim that the patients respect the doctors more than the nurses. Is it because they have a superior education? Is it because the letters at the end of their name are intimidating? No, it is because the doctors have control over when the patients can and cannot leave. A third aspect of the unspoken code between doctors and patients is, “Only the physician has the knowledge and skills to decide when to discharge the patient” (Ibrahim, Kent Kwoh, and Krishnan 2207). The presupposition, assumptions made based on the context of a situation or text, leads the patients to openly respect the doctors more than the nurses (Porter 35). The observation that supports the patients’ understanding of presupposition is that I did not have one example of witnessing a patient asking a nurse when they could leave. They only asked the doctor this. I observed many examples of patients showing respect for the doctor, and also a couple examples of patients not respecting the other staff. First of all, almost every single patient thanked the doctor upon her leaving; that is a sign of respect. One of the Harris 7 nurses specifically came in to request that the doctor go talk to a patient’s son, because he had been butting heads with her all morning, she followed it by saying of course he was nice to you, “you are the doctor”. On multiple occasions, the doctor was requested specifically to discuss medication with the patients, not because the nurses were incapable of explaining it, but because the patients wanted the explanation additionally from the doctor. My conclusion is that this respect for the doctor is based off of the unspoken code referenced earlier. The patients visibly show more patience for the doctor because only the doctor as control over when they can leave, and all of the patients want to leave. There are countless observations that support the claim that the main thing on patients’ mind is they want to leave the hospital. Within the community of the fourth floor of Halifax Hospital, in order to fit in to the discourse as a patient, these many observed patterns that most patients engage in all lead to this claim. The number one example supporting the claim is the simple observation that almost every patient asks the doctor when they will be able to leave. The patients express a level of discomfort, through asking for changes in their treatment plan, further supporting their desire to leave. The patients show a level of lack of presence in their situation by distracting themselves with technology and texts. The patients show more respect for the doctors than the nurses, because the doctors have immediate control over how long their stay will be, and the nurses don’t. The contribution this paper has on the research community of hospitals is to further explain the reasons why patients have a strong urge to leave. Through observation it supports and applies the unspoken code between doctors and patients that was established by Ibrahim, Kent Kwoh, and Krishnan (2207). It can be particularly Harris 8 useful when studying in the future why patients discharge themselves against medical advice. Many studies have been done statistically, by crunching numbers, to decipher what factors contribute to patients self discharging (such as ethnicity, income, insurance, etc.). What differentiates this study is it delves in to the psychology of the patient, not just the numbers and facts. This study contributes to the field of research of hospital patients because it adds a personal explanation to the meaning of what is behind the statistics about patients leaving hospitals established by other studies. Work Cited Gee, James Paul. “What is Literacy?” Becoming Political: Readings and Writings on the Politics of Literacy Education (2001): 1-9. Print. Harris, Sam. “Navigating New Situations Using Literacy” (2014): 1-8. Print. Ibrahim, Said A., C. Kent Kwoh, and Eswar Krishnan. "Factors Associated With Patients Who Leave Acute-Care Hospitals Against Medical Advice." American Journal Of Public Health 97.12 (2007): 2204-2208. Business Source Premier. Web. 22 Apr. 2014. Porter, James E. “Intertextuality and the Discourse Community.” Rhetoric Review 5.1 (1986): 34-47. Print.