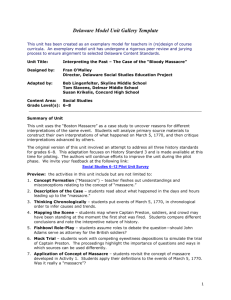

8.1.1 - Boston Massacre

advertisement

Boston Massacre American Revolution From: UCI History Project, Nicole Gilbertson, 2014 History Standards: 8.1.1 Describe the relationship between the moral and political ideas of the Great Awakening and the development of revolutionary fervor. CCSS Standards: Reading, Grades 6-8 1. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. 2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions. 5. Describe how a text presents information (e.g., sequentially, comparatively, causally). 6. Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts). 7. Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts. 8. Distinguish among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text. 9. Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic. Guiding Question: What occurred during the Boston Massacre? Overview of Lesson: The Boston Massacre is a historical event that has been exaggerated in many respects over centuries of retelling. Students will be given multiple sources to examine in order to determine what really happened. Ask students what the word “massacre” means. What qualifies as a massacre? Why would that word be chosen over words like “revolt”, “rebellion”, “streetfight”, etc? Explain to students what today’s objective is – to find out the truth about the Boston Massacre. Familiarize them with the “Reading Like A Historian” handout, and have them get into groups of 4. Each team member will receive one source. It is their job to use the handout on their source in order to determine whether the document is likely to be accurate, or what biases it may have. Students should complete the before and after reading portions individually (allow 10-15 minutes), and then they should share their findings with their group members (allows 15 minutes). Once all of the groups have shared, ask for volunteers (or randomly select some) to share a summary of each document with the whole class. Where was the document from, and who created it? What does it say? Does the handout lead you to believe this is a good source? What biases might this source have? After all sources have been presented, give students all of the sources as well as a homework assignment: to write a summary of what THEY believe happened during the Boston Massacre. Sources: 2 Smithsonian readings, one textbook excerpt, and a picture by Riveres. Home Historical Topics Fact, Fiction: Document A Document A: “Recollection of George Hewes” from James Hawkes’s A Retrospect of the Boston Tea Party (New York, 1834) Beginning in the mid‐1760s, colonists began taking to the streets in Boston and other port cities. Crowds of artisans and laborers joined the elite in protesting British policies, although their differing points of view revealed the divisions within colonial society. Protests mounted in 1767 when Britain passed the Townsend Act, which included a series of unpopular taxes. In Boston, resentment and tension also grew over the presence of British troops, quartered in town to discourage demonstrations, who were also looking for jobs. A private seeking work at a rope maker’s establishment sparked a confrontation on Boston’s King Street. When some in the crowd pelted the assembled British soldiers, the troops opened fire; five colonists were killed and six wounded. George Robert Twelves Hewes, a Boston shoemaker, participated in many of the key events of the Revolutionary crisis. Over half a century later, Hewes told James Hawkes about his presence at the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party. We have been informed by the historians of the revolution, that a series of provocations had excited strong prejudices, and inflamed the passion of the British soldiery against our citizens, previous to the commencement of open hostilities; and prepared their minds to burst out into acts of violence on the application of a single spark of additional excitement, and which finally resulted in the unfortunate massacre of a number of our citizens. On my inquiring of Hewes what knowledge he had of that event, he replied, that he knew nothing from history, as he had never read any thing relating to it from any publication whatever, and can therefore only give the information which I derived from the event of the day upon which the catastrophe happened. On that day, one of the British officers applied to a barber, to be shaved and dressed; the master of the shop, whose name was Pemont, told his apprentice boy he might serve him, and receive the pay to himself, while Pemont left the shop. The boy accordingly served him, but the officer, for some reason unknown to me, went away from the shop without paying him for his service. After the officer had been gone some time, the boy went to the house where he was, with his account, to demand payment of his bill, but the sentinel, who was before the door, would not give him admittance, nor permit him to see the officer; and as some angry words were interchanged between the sentinel and the boy, a considerable number of the people from the vicinity, soon gathered at the place where they were, which was in King street, and I was soon on the ground among them. The violent agitation of the citizens, not only on account of the abuse offered to the boy, but other causes of excitement, then fresh in the recollection, was such that the sentinel began to be apprehensive of danger, and knocked at the door of the house, where the officers were, and told the servant who came to the door, that he was afraid of his life, and would quit his post unless he was protected. The officers in the house then sent a messenger to the guardhouse, to require Captain Preston to come with a sufficient number of his soldiers to defend them from the threatened violence of the people. On receiving the message, he came immediately with a small guard of grenadiers, and paraded them before the customhouse, where the British officers were shut up. Captain Preston then ordered the people to disperse, but they said they would not, they were in the king’s highway, and had as good a right to be there as he had. The captain of the guard then said to them, if you do not disperse, I will fire upon you, and then gave orders to his men to make ready, and immediately after gave them orders to fire. Three of our citizens fell dead on the spot, and two, who were wounded, died the next day; and nine others were also wounded. The persons who were killed I well recollect, said Hewes; they were, Gray, a rope maker, Marverick, a young man, Colwell, who was the mate of Captain Colton; Attucks, a mulatto, and Carr, who was an Irishman. Captain Preston then immediately fled with his grenadiers back to the guardhouse. The people who were assembled on that occasion, then immediately chose a committee to report to the governor the result of Captain Preston’s conduct, and to demand of him satisfaction. The governor told the committee, that if the people would be quiet that night he would give them satisfaction, so far as was in his power; the next morning Captain Preston, and those of his guard who were concerned in the massacre, were, accordingly, by order of the governor, given up, and taken into custody the next morning, and committed to prison. 9/9/2014 Home Smithsonian Source Historical Topics Fact, Fiction: Document B Document B: Excerpt from A Household History for All Readers by Benson J. Lossing (New York: Johnson and Miles, 1877) “What was the Boston Massacre?” This event was a forerunner of a more serious one a few days afterward. John Gray had an extensive ropewalk in Boston, where a number of patriotic men were employed. They often bandied coarse taunts with the soldiers as they passed by. On Friday, the 2nd of March (1770), a soldier who applied for work at the ropewalk was rudely ordered away. He challenged the men to a boxing‐match, when he was severely beaten. Full of wrath he hastened to the barracks, and soon returned with several companions, when they beat the rope‐makers and chased them through the streets. The citizens naturally espoused the cause of the rope‐makers, and many of them assembled in the afternoon with a determination to avenge the wrongs of the workmen. Mr. Gray and the military authorities interfered, and prevented any further disturbance then. But vengeance only slumbered. It was resolved, by some of the more excitable of the inhabitants, to renew the contest; and at the barracks the soldiers inflamed each other's passions, and prepared bludgeons. They warned their particular friends in the city not to be abroad on Monday night, for there would be serious trouble. Fresh wet snow had fallen, and on Monday evening, the 5th of March, frost had covered the streets of Boston with a coat of ice. The moon was in its first quarter and shed a pale light over the town, when, at twilight, both citizens and soldiers began to assemble in the streets. By seven o’clock full seven hundred persons, armed with clubs and other weapons, were on King (now State) street, and, provoked by the insolence and brutality of the lawless soldiery, shouted: “Let us drive out these rascals! They have no business here— drive them out!” At the same time parties of soldiers (whom Dalrymple had doubtless released from the barracks for the purpose of provoking the people to commit some act of violence, and so give an excuse for letting loose the dogs of war) were going about the streets boasting of their valor, insulting citizens with coarse words, and striking many of them with sticks and sheathed swords. Meanwhile the populace in the street were increasing in numbers every moment, and at about nine o'clock in the evening, they attacked some soldiers in Dock Square, and shouted: “Town‐born, turn out! Down with the bloody‐backs!” They tore up the stalls of a market, and used the timber for bludgeons. The soldiers scattered and ran about the streets, knocking people down and raising the fearful cry of Fire! At the barracks on Brattle Street, a subaltern at the gate cried out, as the populace gathered there, “Turn out! I will stand by you; knock them down? kill them! run your bayonets through them!” The soldiers rushed out, and, leveling their muskets, threatened to make a lane paved with dead men through the crowd. Just then an officer was crossing the street, when a barber’s boy cried out: “There goes a mean fellow, who will not pay my master for shaving him.” A sentinel standing near the corner of the Customhouse ran out and knocked the boy down with his musket. The cry of fire and the riotous behavior of the soldiers caused an alarm‐bell to be rung. The whole city was aroused. Many men came out with canes and clubs for self‐defense, to learn the occasion of the uproar. Many of the more excitable citizens formed a mob. Some of the leading citizens present tried to persuade them to disperse, and had in a degree gained their respectful attention, when a tall man, covered with a long scarlet cloak and wearing a white wig, suddenly appeared among them, and began a violent harangue against the government officers and the troops. He concluded his inflammatory speech by boldly shouting: “To the main‐guard! to the main‐guard! There is the nest!” It is believed that the orator in the scarlet cloak was Samuel Adams. The populace immediately echoed the shout—“To the main‐guard!” with fearful vehemence, and separating into three ranks, took different routes toward the quarters of the main‐guard. While one division was passing the Custom‐house, the barber's boy cried out: “There's the scoundrel who knocked me down!” A score of voices shouted, “Let us knock him down! Down with the bloody‐backs! Kill him! kill him!” The crowd instantly began pelting him with snow‐balls and bits of ice, and pressed toward him. He raised his musket and pulled the trigger. Fortunately for him it missed fire, when the crowd tried to seize him. He ran up the Customhouse steps, but, unable to enter the building, he called to the main‐guard for help. Captain Preston, the officer of the day, sent eight men, with unloaded muskets but with ball‐cartridges in their cartouch boxes, to help their beleaguered comrade. At that moment the stout Boston bookseller, Henry Knox (who married the daughter of General Gage's secretary and was a major‐general of artillery in the army of the Revolution), holding Preston by the coat, begged him to call the soldiers back. "If they fire," said Knox, "your life must answer for the consequences." Preston nervously answered: "I know what I am about," and followed his men. When this detachment approached, they, too, were pelted with snow‐balls and ice; and Crispus Attucks, a brawny Indian from Nantucket, at the head of some sailors, like himself (who had led the mob in the attack on the soldiers in Dock Square), gave a loud war‐whoop and shouted: "Let us fall upon the nest! the main‐guard! the main‐ guard!" The soldiers instantly loaded their guns. Then some of the multitude pressed on them with clubs, struck their muskets and cried out, "You are cowardly rascals for bringing arms against naked men." Attuck shouted: "You dare not fire!" and called upon the mob behind him: "Come on! don't be afraid! They daren't fire! Knock them down! Kill 'em!" Captain Preston came up at that moment and tried to appease the multitude. Attucks aimed a blow at his head with a club, which Preston parried with his arm. It fell upon the musket of one of the soldiers and knocked it to the ground. Attucks seized the bayonet, and a struggle between the Indian and the soldier for the possession of the gun ensued. Voices behind Preston cried out, "Why don't you fire! why don't you fire?" The struggling soldier hearing the word fire, just as he gained possession of his musket, drew up his piece and shot Attucks dead. Five other soldiers fired at short intervals, without being restrained by Preston. Three of the populace were killed, five were severely wounded (two of them mortally), and three were slightly hurt. Of the eleven, only one (Attucks) had actually taken part in the disturbance. The crowd dispersed; and when citizens came to pick up the dead, the infuriated soldiers would have shot them, if the captain had not restrained them. Historical Reading Skills Sourcing (Before reading document) Questions What is the author’s point of view? Why was it written? When was it written? Is this source believable? Why? Why not? Students should be able to . . . Identify author's position on historical event Identify and evaluate author's purpose in producing document Predict what author will say BEFORE reading document Contextualization Close Reading Corroboration What else was going on at the time this was written? What was it like to be alive at this time? What things were different back then? What things were the same? What claims does the author make? What evidence does the author use to support those claims? How is this document make me feel? What words or phrases does the author use to convince me that he/she is right? What information does the author leave What out? do other pieces of evidence say? Am I finding different versions of the story? Why or why not? What pieces of evidence are most believable? Evaluate source's believability/ trustworthiness by considering genre, audience, and author's purpose. Use context/background information to draw more meaning from document Infer historical context from document(s) Recognize that document reflects one moment in changing past Understand that words must be understood in a larger context Identify author’s claims about event Evaluate evidence/reasoning author uses to support claims Prompts This author probably believes… I think the audience is… Based on the sourcing information, I predict this author will… I do/don’t trust this document because… I already know that _ at this time… is happening From this document I would guess that people at this time were feeling… This document might not give me the whole picture because … I think the author chose these words because they make me feel… The author is trying to convince me… (by using/saying…) Evaluate author’s word choice; understand that language is used deliberately Establish what is true by comparing documents to each other Recognize disparities between two accounts This author agrees/ disagrees with… This document was written earlier/later than the other, so…