Sea to Sky Burning and Smoke Control Strategic Framework

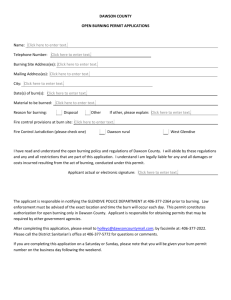

advertisement