1285783085_433966

advertisement

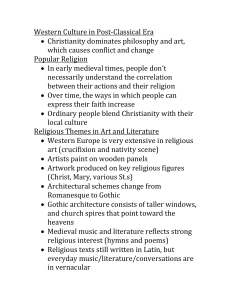

I. II. FORMING CHRISTIAN SOCIETIES IN WESTERN EUROPE A. Environment and Expanding Christianity 1. Between 500 and 900, a cooling climate, incursions by migrating Germanic groups, and reappearing outbreaks of plague drove people to religion in their despair. 2. Western Europe benefitted from favorable geography, including fertile, well-watered plains, a long coastline with fine harbors, and long navigable rivers such as the Danube and Rhine. 3. The Christian Church, through local bishops and monasteries, became the major source of authority as the power of the Roman Empire faded. 4. Christianity mixed with German values and practices, turning pagan worship sites into churches, changing amulets or charms into medals honoring Jesus or the Virgin Mary, and valuing warriors and fighting. 5. The Church sponsored religious orders, and monasteries grew their own food and offered social services such as shelter, emergency food, and clothing for the poor. B. The Frankish and Holy Roman Empires 1. Muslim armies conquered most of Spain and raided Italy and France. 2. Charles Martel defeated the Muslims at the Battle of Tours in 732. 3. Frankish king Pepin the Short came to the aid of Pope Stephen in 753 and donated land in central Italy to the Church in 756; this “Donation of Pepin” was the basis for the Papal States. 4. The Carolingians were named after their greatest leader, Charlemagne (Carolus Magnus) (r. 768–814), who promoted education and Christianity spread Frankish power through much of western Europe, and was crowned “Emperor of the Romans” in 800. 5. Charlemagne’s empire was divided among his grandsons in 843 at the Treaty of Verdun. 6. The Saxon ruler Otto I (a.k.a. Otto the Great) (r. 936–973) established order in Germany and northern Italy, for which a grateful pope made him “Roman Emperor” in 962; after this, rulers in Germany called their lands the “Holy Roman Empire.” C. Vikings and Other Invaders 1. The biggest threat to the European heartland came from the Scandinavian Vikings, or Northmen, who used shallow-draft boats to conduct raids on coasts and up rivers, sailing as far as Byzantium. 2. Eventually the Scandinavians adopted Christianity and established the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. 3. The Vikings influenced a democratic ideal and based settlements across the north Atlantic in Greenland, Iceland, and Canada. 4. The Slavic Bulgars migrated from Russia, settling in Bulgaria in Central Europe; likewise, the warlike Magyars settled in the Hungarian plain after Otto the Great defeated their bid for conquest of Germany and Italy in 955. D. Early Medieval Trade, Muslim Spain, and Technology 1. The Italian cities of Venice and Genoa competed for trade with Byzantium and the Middle East. 2. Christian Europe benefitted from increased trade and contact with the Muslim world and its knowledge of Asian science and classical Greek thought. 3. Several developments crucial for medieval European agriculture increasing the food supply were the moldboard plow, the horseshoe from Central Asia, the horse collar from China, the three-field system of crop rotation, and watermills. MEDIEVAL SOCIETIES, THOUGHT, AND POLITICS A. The Emergence of Feudalism 1. Though some historians consider the term to be an overgeneralization, feudalism was a decentralized social, political, and economic system with a weak central monarchy ruling B. C. D. over smaller states that were mostly autonomous but owed service obligations to the monarchy. 2. A lord (ruler), granted benefices (independent land holdings; also called fiefs), to his vassals (subordinates) in exchange for oaths of personal loyalty and promises of military service. 3. A vassal could subdivide fiefs, giving them to his own subordinates. 4. Knights with warhorses and elaborate armor paid for by vassals, owed loyalty to their lords and followed a strict code of chivalry that included being ferocious in battle, but courteous, generous, and loyal to his friends and dependents. 5. Mounted cavalry was possible because of the stirrup, a Chinese invention brought to Europe by Central Asians. Manors, Cities, and Trade 1. Rural economy was based upon manorialism and its autonomous, nearly self-sufficient agricultural estates, often organized around a castle. 2. Serfs were peasants legally bound to their lord and tied to the land. 3. Serfs were warned to work hard to achieve eventual reward in Heaven. 4. Slavery was an important part of the medieval world, forming about 10 percent of the English population and being common in Italy and Spain. 5. Compared to Byzantium, China, and the Islamic world, early medieval western Europe was economically underdeveloped with small cities. 6. Some medieval people considered cities to be degenerate places, but urban life and economic opportunities attracted people to leave their manors. 7. Cities operated outside the structure of feudalism; a serf able to spend a year and a day in a city without being caught was considered legally free, and craftsmen and merchants organized guilds to protect their interests from feudal obligations. 8. Merchants did not fit into the three feudal categories of those who prayed (clergy), fought (knights), and worked (serfs), and were resented for their traveling and wealth seeking; they organized themselves into guilds to protect their interests. 9. Greed was considered a serious sin, as was the practice of loaning money at interest (usury), although even popes borrowed money at interest from Italian bankers and Jews, who were not subject to Christian prejudices against money lending. 10. Commerce was central to Europe’s economy; as long-distance commerce expanded between 1100 and 1350, prejudice against merchants declined and major trading centers arose, often based upon town fairs. Social Life and Groups 1. Medieval society was patriarchal with men supporting the family and women running the house and raising children. 2. Parents preferred sons, who passed on the family line, property, and name. 3. Society had conflicting views of women, who were considered both depraved and evil but were the objects of devotion, such as the Virgin Mary. 4. The ideal of courtly love promoted by wandering troubadors in the 1100s elevated the status of aristocratic women and promoted usually unrequited romantic love outside of marriage. 5. Homosexuality was tolerated until the thirteenth century, when the Church launched violent campaigns against heresy and unconventional behavior; in 1250 homosexuality was legal and by 1300 it was a capital offense. 6. Christians were hostile to outsiders such as Muslims, whom they called pagans, and after 1150 to Jews. 7. Reformers criticizing church corruption, such as the Albigensians in southern France, were labeled heretics and attacked. The Church as a Social and Political Force 1. E. F. Though powerful socially and politically, the Church experienced turmoil during the High Middle Ages. 2. Medieval Christians measured the stages of their lives by sacramental rites such as baptism and marriage, which were administered by priests and were considered necessary for salvation. 3. Clergy could excommunicate troublemakers, causing psychological devastation. 4. Some priests were corrupt and took bribes, and many had so little education that they could barely recite the Latin liturgy. 5. During the eleventh century, reformers tried to change the Church and its abuses, such as the practice of simony, where the wealthy paid money to have their sons appointed bishops. 6. In 1059 the Church created the College of Cardinals to keep European rulers from interfering in papal elections. 7. Innocent III (r. 1198–1216) extended papal authority over secular rulers and forced Jews to wear distinctive clothing and punished heretics. 8. The Holy Inquisition, created in 1231, used torture and starvation to extract confessions from suspects before executing them, often by burning. 9. Christians adopted ancient Jewish ideas about nature and history, including the concept of progress; to many Christians, God planned the world and the natural environment for human benefit. 10. Some Christians, such as St. Francis of Assisi (1182–1226), and Jews, such as Moses Maimonides, argued that nature was part of God’s creation and required protection. New European States 1. Threatened by increasing papal power, rulers sought to centralize control over their lands. 2. English king Henry II (r. 1154–1189) expanded the power of the royal courts over feudal and Church courts. 3. King John weakened royal power in1215 by signing the Magna Carta (“Great Charter”) limiting the rights of the king and affirming those of the nobles, the Church, and merchants. 4. King Henry III (r. 1216–1272) also contributed to the rise of representative government by waging wars and demanding taxes so that rebellious barons called a parliament (“speaking place”) in 1265 to air their grievances. 5. In France, the Capetian dynasty (987–1328) strengthened the royal bureaucracy under Philip II (r. 1180–1223) and arrested Jews, burned Knights Templars, and attacked the pope under Philip the Fair (r. 1285–1314); from 1305 to 1377, the College of Cardinals bowed to French pressure, electing mostly French popes, who led the Church from Avignon in southern France. 1. German rulers, such as the Hohenstaufen dynasty (Holy Roman Emperors between 1152–1254), spent too much time trying to control Italy and the pope, which enabled the German feudal nobility to retain too much power; Germany did not achieve territorial unity for another 700 years. The Crusades and Intellectual Life 1. Religious and political tensions within Europe fostered a series of Crusades, holy wars against Muslims in Palestine between 1095 and 1272. 2. Pope Urban II launched the first crusade in 1095 by fabricating Muslim Turk atrocities against Christians, prompting the Christian conquest of Jerusalem and mass slaughter of its inhabitants, who viewed crusaders as pirates and terrorists. 3. Guilds of scholars founded the most famous European universities at Paris, Oxford, Salerno, and Bologna; students studied the seven liberal arts: astronomy, geometry, arithmetic, music, grammar, rhetoric, and logic, before specializing in higher studies in medicine, law, or philosophy. 4. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), a Dominican monk and professor, argued that reason could determine much, but eventually a believer had to accept on faith many mysteries; some thinkers were influenced by Aristotle, arguing that real knowledge came only from direct observation, a position that supported scientific inquiry. 5. Literature was diverse, ranging from the warlike and masculine Song of Roland to stories of romantic love and individualism, such as those of King Arthur, Guinevere, and Lancelot. III. EASTERN EUROPE: BYZANTINES, SLAVS, AND MONGOLS A. Byzantium and Its Rivals 1. Fighting between the Sassanian Persian and Byzantine empires weakened both, making easier Arab conquests at their expense, although Constantinople withstood sieges in 673 and 717. 2. Slavic threats came from the Bulgars and Serbs; the defeat of the Bulgars allowed the Serbs to set up several states in the Balkans, bringing them into conflict with Byzantium. 3. The Serbs were eventually conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1459. 4. Norman knights drove Byzantine forces from southern Italy, and Seljuk Turks took eastern Anatolia in 1071 at the Battle of Manzikert. 5. The Byzantines were under constant attack by Persians, Bulgars, Slavs, and Christians, but survived until 1453 when conquered by the Turks. 6. The expanding Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople in 1453, ending the Byzantine state and renaming the ancient city Istanbul. 7. The Byzantine Empire survived as long as it did because of its economic and religious strengths, with the merchants a vital part of Byzantine society and governments dominating the church. 8. Byzantine Church and State were intertwined, and rulers regularly interfered in Church affairs. 9. Although the Byzantine Church was patriarchal, a few women such as Empress Irene (r. 780–802) held power. B. Byzantium, Russians, and Mongols 1. Byzantine culture and religion spread north and east, which enabled them to survive the empire’s defeats. 2. In the ninth century, Saints Cyril and Methodius converted many Slavs to eastern Christianity, devising the Cyrillic alphabet to translate the Bible from Greek into Slavic languages. 3. The Bulgars, Serbs, Russians and many Ukrainians eventually adopted Byzantine culture, including Orthodox Christianity; other Slavs, including the Croats, Czechs, Lithuanians, Poles, Slovaks, Slovenes, and other Ukrainians adopted Roman Catholicism. 4. Russians descended from the Rus, whose capital was Kiev, in today’s Ukraine. 5. Swedish Vikings, trading in Slavic regions beginning around 825, assimilated and became the Rus ruling class. 6. The Rus ruler Vladimir I (ca. 956–1015) became an Orthodox Christian so he could marry a Byzantine princess; he ordered his soldiers to be baptized as Eastern Orthodox Christians. 7. Mongol armies repeatedly sacked Russian cities, beginning in 1237. 8. The Mongol state of the Golden Horde on the lower Volga River controlled most Russians until the fifteenth century. 9. In 1241 large Mongol armies defeated Polish and Hungarian forces, but Western Europe was spared invasion because the death of Genghis Khan’s son Ogodei in Asia meant the recall of the Mongols to Mongolia. 10. Muscovy became the dominant Russian state when Ivan III (1440–1505) escaped Mongol control and started to call himself czar (“Caesar”). 11. The Russian Orthodox Church broke from the patriarch of Constantinople, and Russian clergy referred to Moscow as a third Rome, home of the purest version of Christianity. IV. LATE MEDIEVAL EUROPE AND THE ROOTS OF EXPANSION A. The Black Death and Social Change 1. The climate turned colder about 1300, resulting in the “Little Ice Age” leading to food shortages because of Europe’s shorter growing season. 2. In 1347 a trading ship from the Black Sea brought the Black Death, or bubonic plague, to Sicily; the disease, carried by fleas, spread throughout Europe, killed a third of all Europeans by 1350 and decreasing the population from 70-75 million to 45-50 million people. 3. The plague struck all classes, but the upper classes suffered the greatest long-term effects as peasants demanded more privileges, and nobles were already weakened by royal centralization. 4. The Black Death took less of a toll on eastern Europe because it had fewer towns and more villages. 5. Many Europeans assumed that the pandemic was divine punishment; some people, looking for scapegoats, blamed outsiders, and Jews were driven out of cities or burned alive, especially in the German states. B. Warfare and Political Centralization 1. Chronic warfare strengthened kings and states. 2. In the Hundred Years War (1337–1453), French peasant maid Jeanne d’Arc (ca. 1412– 1431), who believed that she heard saints guiding her, led her forces to victory at Orleans before being burned at the stake by the English. 3. The French kings gained by introducing new taxes and employing mercenaries rather than depending upon nobles’ military forces. 4. England’s defeat in the Hundred Years War precipitated the War of the Roses (1455– 1485), out of which Henry VII founded the Tudor dynasty, which became a world power during the 1500s. 5. The reconquest of Spain from the Muslims began in 1085 and culminated with the capture of Granada and the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. 6. Aristocracy remained strong in the Holy Roman Empire, which encompassed many German-speaking lands and parts of Italy, and where from 1273 the Habsburg family focused on increasing their personal territorial holdings but were unable to create a strong central state. C. Hemispheric Connections, New Intellectual Horizons, and Technology 1. The Late Middle Ages fostered new intellectual horizons and technologies, many derived from Asian and African contacts. 2. The Ottoman ruler, Mehmed the Conqueror (1430–1481), encouraged a flowering of ancient texts and Italian merchants, craftsmen, artists, and architects to work in Istanbul. 3. Moral and political corruption led to a decline of papal political power and the Roman Church; the “Great Schism” (1378-1417) damaged the Church’s prestige. 4. The Renaissance (“rebirth”) began in the Italian city-states about 1350, intensifying and spreading during the 1400s and 1500s. 5. Renaissance philosophy was called Humanism; it promoted vernacular works such as Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy. 6. D. E. Modern scholars disagree about the role of the Renaissance in the larger growth of individualism, secularism, and scientific inquiry in Europe, but it does appear to have emphasized tolerance of diverse views and a more creative and secular worldview among educated people. 7. Extraordinary technological developments, mostly imports from Asia, included the spinning wheel, the compass, stern-post rudder, lateen sails, gunpowder, and—most significantly—movable type for printing, which undermined feudalism and the church. Population and Economic Growth 1. The population of Europe increased 40–50 percent from the tenth to fourteenth centuries, the highest growth rate in the world, accompanied by growth in agriculture and commerce. 2. Contacts from outside Europe stimulated the European economy, such as the techniques of Arab accounting and goods like African gold, and foreign trade expanded, making commerce part of everyday life. 3. The power of western European cities and merchants was unique in the world, giving them unparalleled influence in later European expansion. The Portuguese and Maritime Exploration 1. Though their standards of living were lower than the Africans and Asians they encountered, the Portuguese had better ships, guns, and appetite for conquest. 2. The Portuguese Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) sent caravels (small ships) south along the Atlantic coast of Africa, discovering Madeira Island, the Azores, and Canary Islands. 3. In search of “Christians and spices” in the Asian market, Portuguese ships under Bartolomeu Dias reached the Indian Ocean in 1487, and Christopher Columbus sailed west in 1492.