here - Jane Goodall Institute Australia

advertisement

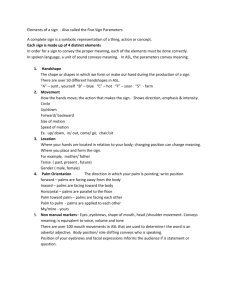

Palm Oil Policy Author: Natasha Jane Coutts BBioSc. (Advanced) The expansion of oil palm plantations has been identified as a major proponent of deforestation and loss of biodiversity in palm oil producing regions.1 During the period 1990-2005, 56% and 55-59% of oil palm plantation expansion in the two prominent production regions, Indonesia and Malaysia, respectively, was at the detriment of natural forest landscapes.2 The tropical forests of these regions are recognised as biodiversity hotspots: complex ecosystems that support many endemic animal and plant species, some of which are listed by The IUCN Red List as being critically endangered, e.g. Sumatran orang-utan, Sumatran tiger, Sumatran rhinoceros and Sumatran elephant.3 Much of the landscape of the production regions also consists of peatlands: areas that act as carbon sinks due to waterlogged soils that prevent the complete decomposition of organic matter. 4 When disturbed, peatlands release those carbon stores in to the atmosphere in the form of greenhouse gas. 4 Deforestation further exacerbates this issue, as the natural vegetation is replaced with oil palm trees that have been shown to be far less efficient at carbon sequestration.1 In addition to these environmental issues, negative social impacts also abound. An extensive number of documented accounts exist, which detail the displacement of local and indigenous peoples that, until the expansion of the oil palm industry, had subsisted for generations within the forest areas.5 Land acquisition has often been under illegal and misleading pretences, resulting in lengthy land rights disputes between the indigenous peoples and the production companies.6 Plantation workers have been subjected to suboptimal working conditions and wages, both of which contribute to the relatively high staff turnover rates and low staff morale observed within the industry. 7 Coupling the aforementioned environmental and social issues plaguing the palm oil industry, it is clear to see why concerned NGOs and public consumers have insisted that an industry-wide reform, geared toward developing more sustainable practices, must be instigated. And thus the Round Table for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was born. Initiated in 2004, the RSPO is a multi-stakeholder organisation with members representative of each sector of the palm oil industry, namely growers, producers, processors, traders, consumer goods manufacturers, retailers, banks and investors, as well as environmental and social NGOs and individuals associated with the industry.8 At present, there are more than 1300 RSPO members who account for one third of the processors, one third of consumer goods manufacturers and 17% of producers globally.7, 9 Through consensus, members have developed eight key principles and criteria fundamental to achieving a transparent, legally compliant, economically viable, environmentally appropriate and socially beneficial industry.10 By adhering to these stringent principles and criteria, palm oil growers and producers are able to demonstrate their commitment to creating a sustainable industry and become RSPO certified in return. RSPO certified plantations cover an area greater than 1.7 million hectares and the certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) they produce accounts for approximately 14% of all crude palm oil produced world-wide.11, 12 While this is only a small proportion of the global palm oil market, it is evidence of multiple organisations recognising their environmental and social responsibilities and responding to consumer pressure. Many leading retailers, including Walmart, Nestle, The Body Shop, Woolworths and Coles, have committed to using only CSPO in their products by 2015.13 As public awareness about the negative environmental and social impacts generated by the palm oil industry increases, so too will this trend for retailers to replace conventional palm oil with CSPO in their products as a result of consumer pressure. As a constituent in a variety of common food and household items, as well as being a popular cooking oil in some of the world’s most populous regions, e.g. China, India and Indonesia, the demand for palm oil will continue to grow, coinciding with an increasing human population. It has been estimated that by 2050 agricultural crop yields will need to increase by 70% to sufficiently nourish the global population.14 Oil palm yields are typically seven to ten times larger per hectare than other major oil crops, making it the most economical option available.15 While room still exists for future growth, arable land in South East Asia is becoming progressively scarce.16 This has caused oil palm developers to seek out alternative regions to expand their enterprises. Central Africa, more specifically the Congo Basin, has been identified as a decidedly viable location by many palm oil development organisations. The Congo Basin encompasses five different countries, Cameroon, Gabon, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Central African Republic (CAR) and Republic of Congo, and is covered by the world’s second largest contiguous tropical forest. Many threatened species inhabit this forest, including each of Africa’s extant great apes- gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos. Approximately two-thirds of the total forest area has a climate and soil conducive to oil palm propagation.1, 17 Multiple small-scale oil palm plantations are already in operation within this region and, until recently, have seen little to no growth since their initial colonial-era inception.17 However, since 2010, many oil palm production companies already operating in South East Asia have planned, or in some cases already begun, the development and expansion of industrial-scale plantations that will increase the total production area by five times its current size over the entire Congo Basin region. 17 Disturbingly, many of the questionable practices observed in the South East Asian plantations prior to the inception of the RSPO have been reported to be occurring in the Congo Basin, including a lack of transparency regarding the agreement terms between developers and governments, documents outlining development details not being made publicly available and an absence of records detailing local communities’ land rights and potential important natural resources.17 However, despite this situation seeming increasingly dire, many of the mistakes made in the South East Asian region can be avoided in these new Central African developments by implementing the RSPO’s principles and criteria for sustainability. By supporting the RSPO, the Jane Goodall Institute Australia is supporting their vision to transform the entire oil palm market in to one where CSPO is the norm. We support the initiative taken by those companies that have committed to employing sustainable practices and that strive for continuous improvement, and urge all other organisations within the entire palm oil supply chain to do the same. We acknowledge that, while many environmental and social concerns remain unresolved, the RSPO principles and criteria are a work in progress, and as such, will continue to be developed until an industry-wide adoption of best management practices occurs and a uniform level of sustainability is achieved. It is our hope that consumers will too embrace the ideal of a sustainable palm oil industry, and will use their influence as a buyer to persuade retailers to commit to sourcing only CSPO for their products. In addition to the standards and practices employed by the RSPO, the Jane Goodall Institute Australia also supports the initiatives taken by governments, independent NGOs and concerned members of the public to incite positive change within the palm oil industry. This includes the introduction of government policies and laws that prevent the replacement of primary forest with oil palm plantations, and where these policies already exist, the improvement of enforcement measures. We also encourage the work of NGOs who aim to educate the public on the devastatingly negative impacts that the palm oil industry is causing in the producing regions, and their ability to create change through consumer purchasing power. The Jane Goodall Institute Australia believes that supporting the efforts of both the industry-based RSPO and the non-affiliated organisations/individuals is the most effective way to promote positive changes within the palm oil industry. Literature Cited 1 Fitzherbert, E. B., Struebig, M. J., Morel, A., Danielsen, F., Bruhl, C. A., Donald, P. F. and Phalan, B. (2008). How will oil palm expansion affect biodiversity? Cell, 23 (10), 538-545. 2 Koh, L. P. and Wilcove, D. S. (2008). Is palm oil agriculture really destroying tropical diversity? Conservation letters. 1, 60-64. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2013). Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.iucnredlist.org 3 4 5 Tan, K. T., Lee, K. T., Mohamed, A. R. and Bhatia, S. (2009). Palm oil: addressing issues and towards sustainable development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 13, 420-427. Forest Peoples Programme. (2008). Free, prior and informed consent and the Roundtable of Sustainable Palm Oil: a guide for companies. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.rspo.org/sites/default/files/FPIC and Oil Palm Plantations - A Guide for Companies (Oct 08).pdf 6 Forest Peoples Programme. (2006). Promised land: palm oil and land acquisition in Indonesia – implications for local communities and indigenous peoples. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/fpp/files/publication/2010/08/promised landeng.pdf 7 WWF, FMO and CDC. (2012). Profitability and sustainability in palm oil production: analysis of Incremental Financial Costs and Benefits of RSPO Compliance. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/profitability_and_sustainability_in _palm_oil_production__update_.pdf 8 RSPO. (2004). Summary of R2 results by C. H. Teoh. Jakarta: RSPO. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.rspo.org/files/pdf/RT2/Proceedings/Day Results (TCH).pdf 9 2/Summary of RSPO. (2013a). RT11. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.rt11.rspo.org 10 RSPO. (2013b). Principles and criteria for production of sustainable palm oil. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.rspo.org/file/PnC_RSPO_Rev1.pdf 11 RSPO. (2013). CSPO Market performance (Feb 2013). Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.rspo.org/file/CSPO Uptake & Production - Charts-FEB(1).pdf 12 RSPO. (2012). Milestones. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.rspo.org/en/milestones 13 WWF. (2011). 2011 Palm oil buyers’ scorecard. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/footprint/agriculture/palm_oil/solutions /responsible_purchasing/scorecard2011/ 14 FAO. (2012). World agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision (ESA Working Paper No. 12-03). Agricultural Development Economics Division, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. 15 RSPO. (2013). Palm Oil Factsheet. Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.rspo.org/files/pdf/Factsheet-RSPO-AboutPalmOil.pdf 16 USDA. (2013). Indonesia: Palm oil expansion unaffected by forest moratorium (Commodity Intelligence Report). Retrieved November 15, 2013. http://www.pecad.fas.usda.gov/highlights/2013/06/indonesia/ 17 The Rainforest Foundation UK. (2013). Seeds of destruction: expansion of industrial palm oil in the Congo Basin – potential impacts on forests and people. Under the Canopy. 1, 1-72.