Answers to Resident IUD Questionnaire

advertisement

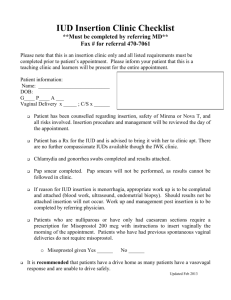

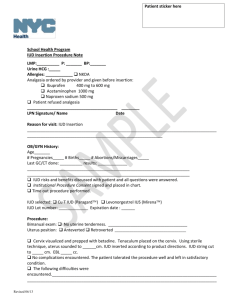

Answers to Resident IUD Questionnaire 14) If 100 women used the IUD correctly for 1 year, what percentage of women would you expect to get pregnant (i.e., what is the failure rate of the IUD)? Answer: < 1%. 0.8% and 0.2% of women will experience an unintended pregnancy within the first year of typical use of the Paragard (Copper T380A) and Mirena IUDs, respectively.1 15) and 16) According to the FDA, the Paragard (Copper T380A) IUD and Mirena IUD should be left in place for a maximum of how many years? Answer: 10 years for the Paragard (Copper T380A), 5 years for the Mirena. The Paragard (Copper T380A) IUD is approved for use in the United States for 10 years, although it has been demonstrated to maintain its efficacy over at least 12 years of use. The Mirena IUD is approved for use in the United States for 5 years, although it is effective for at least 7 years and probably 10 years.2 17) How quickly does fertility typically return after IUD removal? Answer: Immediately. Following removal of IUDs, the normal intrauterine environment is rapidly restored. In large studies, there is no delay, regardless of duration of use, in achieving pregnancy at normal rates. There has been no significant difference in cumulative pregnancy rates between parous and nulliparous or nulligravid women.2, 3 18) What is the overall discontinuation rate for the Paragard (Copper T380A) and Mirena IUDs after 1 year of use? Answer: 0-25%. 78% of women using the Paragard (Copper T380A) IUD and 80% of women using the Mirena IUD are still continuing its use at 1 year.1 19) What is the average expulsion rate for an IUD in the first year after insertion? Answer: 0-15%. Up to 15% of women will expel their IUD within the first year after insertion. Those who have it placed immediately post-partum within 48 hours or post-abortion do have higher expulsion rates of up to 12%4 and 8%,5 respectively, whereas those who have delayed insertion have an expulsion rate of only 3-4%.6 Younger age, a higher than normal amount of menstrual flow, and dysmenorrhea are also associated with higher expulsion rates.7 Evidence suggests that despite the higher expulsion rate post-abortion, it may still decrease repeat abortions since many women do not come back for their post-abortion visit and delayed IUD insertion.8 20) Which IUD(s) is/are FDA-approved to be used as emergency contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy if placed within 5 days of unprotected intercourse? Answer: the Paragard (Copper T380A). The Paragard (Copper T380A) IUD can be inserted up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse to prevent pregnancy and is extremely effective, reducing the risk of pregnancy after unprotected intercourse by 99%.9 21) Which statement(s) below describe(s) the mechanism of action of the IUD? Answer: prevents fertilization and implantation of an embryo. Both the Paragard (Copper T380A) and Mirena IUDs create an intrauterine environment that is spermicidal by producing a sterile inflammatory response within the uterus, which is their primary mechanism of action. The Paragard (Copper T380A) IUD does this by releasing free copper and copper salts into the cervical mucus and endometrium, which inhibits sperm motility through both mediums and releases cytokines in the endometrium that is spermicidal. Very few, if any, sperm reach the ovum in the fallopian tube. Sensitive assays for human chorionic gonadotrophin do not find evidence of fertilization. The Mirena IUD creates a similar effect by releasing a steady amount of 20ug levonorgestrel (progesterone) into the uterine cavity, causing inflammation of the endometrium similar to that of inert IUDs, while also suppressing the endometrial glands and secretions. This process results in endometrial atrophy and inhibits both sperm migration and survival and prevents implantation of any embryos. The progesterone also thickens the cervical mucus, creating a barrier to sperm penetration, and decreases activity of the tubal epithelium, inhibiting transport of both the ovum and sperm in the fallopian tube. The medical definition of conception is considered to be the time of implantation of the blastocyst into the endometrium. Since IUDs do not destroy any implanted embryos, they are not considered abortifacients.2, 10 22) Do IUDs increase a patient’s overall risk of ectopic pregnancy as compared to a patient using a different method of contraception or no contraception? Answer: No. Previous use of an IUD does not increase the risk of a subsequent ectopic pregnancy, and the current use of an IUD actually offers some protection against ectopic pregnancy by the above-mentioned mechanisms of action (i.e., inhibition of sperm motility and function, thereby preventing fertilization). The Mirena IUD has the added benefit of partially suppressing gonadotropins, so that the number of ovulatory cycles is decreased, with less overall opportunity for an ectopic pregnancy to occur. However, if a pregnancy does occur with an IUD in place, the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy is high. A WHO multicenter study concluded that IUD users were 50% less likely to have an ectopic pregnancy when compared with women using no contraception. The risk of ectopic pregnancy does not increase with increasing duration of use with the Paragard (Copper T380A) or Mirena IUD.2 23) Does inserting an IUD increase a patient’s risk of pelvic infection during the first 20 days after insertion? Answer: Yes. A review of the WHO database derived from all of the WHO IUD clinical trials concluded that the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) was six times higher during the 20 days after the insertion compared with later times during follow-up. Of note, PID was extremely rare beyond the first 20 days after insertion. In nearly 23,000 insertions, only 81 cases of PID were diagnosed. A large case-control study from the USA found the increase in risk is limited to the first 4 months after insertion; by 5 months and thereafter, the risk was not significantly increased. Other studies have shown that there is no increased risk of Chlamydia acquisition by IUD users and that the monofilament tailstring that is used in modern IUDs does not increase the risk of infection. The Dalkon Shield had a multifilament string that did increase infection by carrying bacteria cephalad, but has not been manufactured since the 1980s.2, 11, 12 24) Do you routinely give antibiotic prophylaxis prior to IUD insertion? Answer: Per ACOG Practice Bulletin #59 (Intrauterine Device, 1/05), Level A evidence shows that routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of IUD insertion confers very little benefit. It has not been found to decrease the risk of subsequent PID and therefore is not routinely recommended, even for patients who are at risk for subacute bacterial endocarditis (per the American Heart Association). This opinion is based upon four randomized trials and a metaanalysis.13, 14 25) Do you wait until you have negative gonorrhea and chlamydia culture results on ALL patients before inserting an IUD? Answer: According to ACOG Practice Bulletin #59, current data do not support routine screening in women at low risk for STDs.15 Women who are at high risk of STDs may benefit from the screening as a systemic review revealed that women with chlamydial infection or gonorrhea at the time of IUD insertion were at increased risk of PID relative to women without infection, although the absolute risk of PID was still low for both groups (0-5% for those with STIs and 0-2% for those without).15 If a patient’s cultures do come back as positive after an IUD is inserted, it is possible to initially treat with the IUD in place and to remove the IUD only if subsequent PID develops and is non-responsive to treatment.16, 17 26) Do you wait until a patient’s next menses to insert an IUD if you are reasonably certain that she is not pregnant? Answer: The advantages of inserting an IUD during a patient’s menses are that it may be easier due to a more open cervical os, it may mask bleeding from the insertion process, and it creates certainty that the patient is not currently pregnant. However, these advantages must be weighed against the risk of unintended pregnancy if insertion is delayed to await menses.2 Furthermore, the expulsion rate and termination rates for pain, bleeding, and pregnancy are lower if insertions are performed after day 11 of the menstrual cycle, and the infection rate may be lower with insertions after day 17.18 If the patient has been sexually active within 2 weeks and has not been on adequate birth control, one should wait until at least 2 weeks after the last episode of intercourse to obtain a pregnancy test.19 Or, if it is within 5 days of unprotected intercourse, the Paragard (T380A) may be used as emergency contraception. 27) Which off-label non-contraceptive benefits has the Mirena IUD been found to have (please check all that apply)? Answers: improvement of bleeding from menorrhagia, improvement of pain from endometriosis, improvement of pain and bleeding from adenomyosis, protection from endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. According to ACOG Committee Opinion #337 (Noncontraceptive uses of levonorgestrel intrauterine system), there is sufficient evidence to support the use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system as a treatment option for idiopathic menorrhagia and that it protects against endometrial hyperplasia in women using menopausal estrogen therapy. Small pilot studies suggest that it also improves endometriosis-associated pelvic pain for up to 3 years, and therefore the Committee Opinion states that it is reasonable to consider its use by women with endometriosis who desire effective, long-term contraception.20 Three small studies have shown that it also can assist with treatment of adenomyosis by decreasing uterine volume, bleeding, and pain.21 When used in the setting of myomas, it has been shown to reduce menstrual blood loss and pain, but it does not reduce overall uterine size or size of uterine fibroids, and expulsion rates may be higher.22 The Mirena IUD has not been found to offer protection from breast cancer or to improve pain from ovarian cysts. 28) How would you recommend an IUD to a patient in the following situations? Assume no contraindications for use of an IUD and that all other factors are favorable for use. Answer: According to ACOG Practice Bulletin #59, candidates for intrauterine device use include both nulliparous and multiparous women at low risk for sexually transmitted diseases. It may be an optimal method for women with certain medical conditions, including diabetes, thromboembolism (for which Mirena may be ideal if patients are on anticoagulants since it decreases menstrual bleeding), menorrhagia/dysmenorrhea, and breastfeeding. Contraindications include pelvic inflammatory disease within the past 3 months or a current diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease that has been untreated.13 ACOG Committee Opinion #392 addresses the issue of “Intrauterine device and adolescents.” It states that “top-tier methods of contraception, including IUDs and implants, should be considered as first-line choices for both nulliparous and parous adolescents. After thorough counseling regarding contraceptive options, health care providers should strongly encourage young women who are appropriate candidates to use this method.” Because adolescents have the highest rates of chlamydia and co-infection with gonorrhea, all adolescents should be screened for both before IUD insertion, and screening at the time of insertion expedites contraceptive use.23 The 3rd Edition of the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) for Contraceptive Use, published in 2004, is another helpful guide to selecting appropriate candidates for IUD use. It classifies various clinical scenarios of contraceptive use into four different categories. If a condition is classified as Category 1, the contraceptive can used in any circumstances. Category 2 indicates that the method can generally be used, Category 3 indicates that use of the method is not usually recommended unless other more appropriate methods are not available or not acceptable, and Category 4 indicates that the method is not to be used. By this classification system, placing an IUD in a patient who is <48 hours postpartum is considered to be Category 2 for the Copper IUD and Category 3 for the LNG-IUD. However, placement of an IUD immediately after a first-trimester abortion, whether spontaneous or induced, is considered Category 1. For second-trimester abortions, it becomes a Category 2 because of greater risk of expulsion.24 For patients who are infected with HIV, the WHO MEC lists IUD use and insertion as Category 2 for both the copper and levonorgestrel IUDs. The exception is if the patient has AIDS and is not clinically well on anti-retroviral therapy. If this is the case, the IUD becomes a Category 3 for insertion, but it is still a Category 2 for continued use if they already have an IUD in place. If a patient has AIDS but is clinically well on anti-retroviral therapy, it is still Category 2 to insert and continue the IUD. IUD use among HIV-infected women has not been associated with increased risk of transmission to sexual partners, and having an IUD does not increase the risk of HIV acquisition for women without HIV. However, the WHO does suggest that IUD users with AIDS be closely monitored for pelvic infection.24 References 1 Trussell J. Contraceptive efficacy. In: Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Stewart FH, Kowal D, editors. Contraceptive technology: nineteenth revised edition. New York, NY: Ardent Media; 2007. p. 747-826. 2 Speroff L, Darney PD. A Clinical Guide for Contraception, Fourth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins, 2005. p. 230-236. 3 Sivin I, Stern J, Diaz S, et al. Rates and outcomes of planned pregnancy after use of Norplant capsules, Norplant II rods, or levonorgestrel-releasing or copper TCu380Ag contraceptive devices. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:1208-13. 4 Celen S, Moroy P, Sucak A, Aktulay A, Danisman N. Clinical outcomes of early postplacental insertion of intrauterine contraceptive devices. Contraception 2004;69:279-82. 5 Pakarinen P, Toivonen J, Luukkainen T. Randomized comparison of levonorgestrel- and copperreleasing intrauterine systems immediately after abortion, with 5 years’ follow-up. Contraception 2003;68:31-34. 6 Sivin I, Stern J, et al. Prolonged intrauterine contraception: a seven-year randomized study of the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T380 Ag IUDs. Contraception 1991;44:473-80. 7 Zhang J, Feldblum PJ, Chi IC, Farr MG. Risk factors for copper T IUD expulsion: an epidemiologic analysis. Contraception 1992;46:427-433. 8 Goodman S, Hendlish SK, Reeves MF, Foster-Rosales A. Impact of immediate postabortal insertion of intrauterine contraception on repeat abortion. Contraception 2008;78:143-8. 9 Trussell J, Ellertson C. Efficacy of emergency contraception. Fertil Control Rev 1995;4:8-11. 10 Stanford JB, Mikolajczyk RT. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices: Update and estimation of postfertilization effects. AJOG 2002;187:1699-708. 11 Farley MM, Rosenberg MJ, Rowe PJ, Chen JH, Meirik O. Intrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease: an international perspective. Lancet 1992;339:785-88. 12 Grimes DA. Intrauterine device and upper-genital-tract infection. Lancet 2000;356:1013-19. 13 Espey E. ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 59. Intrauterine Device, January 2005. 14 Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Antibiotic prophylaxis for intrauterine contraceptive device insertion (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 204, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 15 Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Peterson HB. Does insertion and use of an intrauterine device increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease among women with sexually transmitted infection? A systematic review. Contraception 2006;73:145-153. 16 Faundes A, Telles E, Cristofoletti ML, Faundes D, Castro S, Hardy E. The risk of inadvertent intrauterine device insertion in women carries of endocervical Chlamydia trachomatis. Contraception 1998; 58:105-9. 17 Skjeldestad FE, Halvorsen LE, Kahn H, Nordbo A, Saake K. IUD users in Norway are at low risk for genital C. trachomatis infection. Contraception 1996;54:209-12. 18 White MK, Ory HW, Rooks JB, Rochat RW. Intrauterine device termination rates and the menstrual cycle day of insertion. Obstet Gynecol 55;22, 1980. 19 Allen RH, Goldberg AB, Grimes DA. Expanding intrauterine access to contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Jun 13 2009, Epub ahead of print. 20 Noncontraceptive uses of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 337. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1479-82. Reaffirmed 2008. 21 Bahamondes L, Petta CA, Fernandes A, Monteiro, I. Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in women with endometriosis, chronic pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea. Contraception 2007;75:S134-139. 22 Kaunitz AM. Progestin-releasing intrauterine systems and leiomyoma. Contraception 2007;75:S130133. 23 Intrauterine device and adolescents. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 392. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1493-1495. 24 WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 3 rd Edition. 2004.