File - The Tarrytown Meetings

advertisement

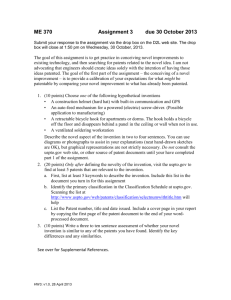

Gene Patents in India K M Gopakumar (TWN) and Visalakshi (Centad) Introduction The question of patenting of life forms came up in India in the context of India’s ratification of the Final Act of the Uruguay Round, which established the World Trade organisation. In order to comply with the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement India amended the Patents Act 1970 in 2002 to introduce patent for life forms. This Act was came into force in 2003 after three years from the original deadline to introduce patent protection for life forms under the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which is part of the e final Act of Uruguay Round. Prior to the amendment Indian Patent Act 1970 denied patent protection to life forms. Even though there was no explicit prohibition against the patenting of life forms Section 3 of the Patents Act, which exclude certain inventions from patent protection. According to Section 3 invention contrary to morality, agriculture and horticulture and treatment of plant and animals were denied patents. However, the This short note explains the current status of biotech patents especially patenting of genes in India. First Part explains the legal provisions on patenting of life forms in India. Second Part discusses the practise of the patent office and the last part provides some empirical evidence and the last part contains certain specific suggestions. Options for the Implementation of Article 27 (3) (b) of TRIPS One of the dominant strategies to implementation of the TRIPS obligation was to use the flexibilities available in the TRIPS agreement. At least five types of flexibilities are available in the implementation of Article 27 (3). First, since there is no definition of invention is provided in the TRIPS Agreement, there is a possibility to make legal difference between invention and discovery and to exclude naturally found microorganisms and other genetic material form the patent protection. Second, flexibility is again comes form the absence of definition of microorganism. Hence, there is a possibility to define microorganisms as a living single cell organism and to exclude part of the plants and animals from patent protection. Third, is to exclude patents on certain life forms including genes using the exception under Article 27 (2) of the TRIPS Agreement, which allows exclusion of patent on public morality. 1 Four establish Members may exclude from patentability inventions, the prevention within their territory of the commercial exploitation of which is necessary to protect ordre public or morality, including to protect human, animal or plant life or health or to avoid serious prejudice to 1 a high threshold level of inventive step criteria and avoid patenting of naturally found bi materials including genes. Five, implement high threshold level for the industrial application criteria and to deny patent on naturally found bio materials including genes. Prior to discuss the limitations on these approaches it is also important to consider the basic limitations in developing countries, which would limit the implementation of TRIPS flexibility. Often it is assumed that every WTO Member State has a same level of progress in science and technology and therefore there is level playing field in terms of understanding the complexities related to patenting of biotechnology. However, the reality there is lack of capacity in many developing countries to understand the development implications of biotechnology in general and especially on the issue of patenting of biotechnology. Second, there is no shared understanding existing among WTO Members with regard to the actual scope of TRIPS flexibilities. This would provide a room for vested interest especially from the developed countries to influence the law and policy framework to minimise the use of TRIPS flexibilities. Often developing country patent laws fails to include pre-grant stage flexibilities to the optimum level. Lastly, there is an asymmetry existing among patent office in terms of their financial and human resource and infrastructure. There fore it would be difficult for many developing country patent offices to implement the flexibilities especially those available at the pre-grant stages of patents. Implementation of the above-mentioned flexibilities depends on the ability of the patent office to apply the flexibilities provided in the domestic law. Generally speaking, these flexibilities can be incorporated in the domestic law in two ways. First, entrusting the patent office to apply the exclusion on a case-to-case basis and determine whether the claimed invention falls within the exclusion. For instance, a broad exclusion of certain invention on the ground public morality. In such cases patent office or the judiciary has to examine whether the claimed invention falls within the exclusion. The problem with this approach is that success depends on the capability of the patent office to apply the law correctly in real context. Further, it also potentially generates litigation and an opportunity for the judiciary to interpret the law, which may go against the policy objective behind the exclusion. Second, to eliminate or limit the freedom of judiciary and the patent office to interpret the law and exclude certain inventions very clearly in the statute. For instance, certain patent statute excludes new use of known substance from patent protection. Considering the inherent capacity deficit in developing countries it is in the interest of the developing countries to exclude explicitly all possible exclusions in the statute on the basis of above mentioned flexibilities. the environment, provided that such exclusion is not made merely because the exploitation is prohibited by their law Scope of Patent Protection In order to comply with the three amendments were carried out on the Patents Act 1970 viz 1999, 2002 and 2005. The last two amendments carried out changes in the definition of patentable criteria and exclusion of patents. Generally speaking, there are two ways to limit the scope of patentability. First, to increase the threshold limit of patentability criteria by providing the definition of patentability criteria, viz. novelty, inventive step and industrial applications. Second, to exclude certain types of inventions, which do not satisfy any one of the patentability criteria, or those inventions, which are in conflict with public morality, national security or affecting the health of humans, animals and plants. The Indian Patents Act attempts to limit the scope of patentability by following both methods. The criteria for patentability are defined in the Act and linked to a web of definitions. According to the Act, a patent means “a patent for any invention granted under this Act”.2 The word ‘invention’ is defined as a “new product or process involving an inventive step and capable of industrial application”.3 Thus a patent is granted only to a new product or process involving an inventive step and capable of industrial application. However, the Act defines ‘inventive step’ as “a feature of an invention that involves technical advances as compared to the existing knowledge or having economic significance or both and that makes an invention not obvious to a person skilled in the art”.4 According to this definition, to qualify the inventive step test the invention has to satisfy any of the three conditions, viz. advances over existing technical knowledge or economic significance or both. Generally speaking, economic significance should not be a sole criterion for evaluating the inventive step of the invention. The economic significance of an invention depends on many other factors and it is not the purpose of patents to recognise economic significance of an invention. However, the new definition makes the economic significance criteria as substitutable criteria to technical effect. As a result, the new definition of inventive step diluted one of the basic requirements of an inventive step. TRIPS uses economic significance in a different context. Under Article 31(l) (ii), TRIPS states that compulsory licence for dependent patent should look at whether the second patent should involve an important technical advance of considerable economic significance in relation to the invention claimed. Therefore, economic significance could have been used along with the technical effect to judge the inventive step, but not as the sole criteria. Therefore, the current definition lowers the threshold level for the inventive step. In short these changes in the definitions does not offer any limitation on the scope of bio technology inventions including patenting of genes. The Section 3 of the Patents Act excludes 16 categories of inventions from patent protection, because they are not considered inventions within the definition of invention. Since these 16 items are not qualified as inventions within the scope of Patents Act claims falls within these 16 items are excluded form patent protection. There are a few exclusions having implications to the patentability of which can applied in the context of biotechnological invention. However the most important 2 Section 2 (m) of Patents Act. 3 Section 2( j) of Patents Act. 4 Section 2(ja) of Patents Act. section for our discussion is Section 3 (b) and 3 (j). According to Section 3(b) an invention which primary intention is commercial exploitation QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Section 3 (j) states that QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Section 3 (j) is a clear that any part of the plant r animals cannot be patented. Thus a plant and animal or nay part of it is not patentable. Even though there is no explicit exclusion of genes or DNAs under this section. However, it is clear that this exclusion includes gene, cell lines, DNA etc. But the practise of patent office suggest that patent office does not share the view that patent claims falls within Section 3 (j) of the Patents Act. For instance, the Draft Patent Manual practise and Procedure 2008 and 2011 edition does not provide nay explanation on Section 3 (j). However the manual while explaining the unity of invention states: (iv) When a genetically modified Gene Sequence/ Amino Acid Sequence is novel, involves an inventive step and has industrial application, the following can be claimed. (a) Gene sequence / Amino Acid sequence (b) A method of expressing above sequence (c) An antibody against that protein / sequence (d) A kit made from the antibody / sequence All of these claims are linked by the inventive concept if the genetically modified sequence is new, inventive and has industrial application This clearly shows that patent for genes are available in India irrespective Section 3 (j). This in a way may be the result of indirect harmonization happening between developed and developing countries. Instead of developing a development oriented jurisprudence developing country patent office looked at developed country patent office for guidance in these areas. This resulted in importation of jurisprudence form developed countries and resulted in the practical harmonization of patent law. As a result the statutory provisions remained only in the statute book without any practical use. For instance, In order to enhance the capacity, the patent office entered into eight Memorandum of Understandings (MoUs) with the developed countries.5 All 5 Indian Patent Office signed MoUs with IP or patent offices of Australia, Germany, Switzerland, Japan, the UK, the US, France and the European Patent Office (EPO). these eight countries are advocates of enhanced patented protection and compromise the strict patentability standards. These MoUs cover human resource development, capacity building activities, exchange of best practices and information exchange. This would lead to importation of the developed country practices through examination process and training of examiners. For instance, the patent office MoU with the US Patent Office (USPTO) states that The Parties shall work together in capacity building in Intellectual Property Rights including automation and modernization of Intellectual Property Offices, development of databases, and procedural rationalization and simplification of processing of Intellectual Property applications, inter alia, through the exchange of information on patent data, best practices in patent examination procedures, etc. The two Parties shall cooperate in the training of personnel and human resource development in the area of Intellectual Property Rights with a view to strengthening the working of the Intellectual Property (IP) systems in the two countries, including in patent examination training.6 As part of the MoU, nearly many patent examiners were trained under USPTO. Hence the manual brings a backdoor harmonization of patent examination standards with the US and the EU patent examination practices. These trainings might have resulted in the above-mentioned interpretation on gene patents in the Manual. During the last 5 years there is an increase in the biotech patent application and its grant. Annual Report provides patent applications received in biotechnology, biomedical, biochemistry and agriculture. The last five years has witnessed an increase in the number of patent application sin these areas. According to the Annual Report of the Indian Patents Office number of biotechnology application has increased form 1214 (2004-08) to 1884 (2008-09). The number patent applications in other related areas are: bio medical application (1106 foreign 68 Indian) , . Bio Chemistry (759 foreign and 119 Indian), Bio informatics (60 foreign and 4 Indian), Agriculture 59 foreign and 29 Indian ). There is also an increase in the number of patents granted in biotechnology sector. During 2004-05 patent office granted only 71-bio technology. This has increased to 1157 2008-09. The numbers of patents granted in new areas are : bio medical application (244 foreign 19 Indian) , Bio Chemistry (1587 foreign and 198 Indian), Bio informatics (0), Agriculture (16 foreign and 4Indian ). However, empirical analyses of granted patents 2005-2008 June shows that patent office granted claims on genes. This analysis was carried out on the basis of scrutiny of title and abstract search. Prima facie suspected gene patents are 6 Articles 3 and 4 of MoU on Bilateral Cooperation between Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Mark and the United States Patent and Trade Mark Office, available at: <http://dipp.nic.in/acts/MOU_of_bilateral_cooperation_with_usa.pdf>, accessed on 25 October 2009. taken up for further analyses, this part is currently under progress. However the preliminary analyses shows that patent have been granted on genes. Annex 1 provides a sample list of such patents. Way Forward Over the years there is an increasing number of pockets of resistance to patenting n life as well as gene. However, the challenge is to translate these resistances into concrete policy action. The following are some of the suggestions. First, in the light of the 15 years of experience there should be pressure on WTO Member sates to carry out the mandatory review under Article 27 (3) (b) and 71. Article 27 (3) (b) states that “The provisions of this subparagraph shall be reviewed four years after the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement”. Hence the scope of this review is broad and the question of life patenting should be opened up. In the past African Group put up a proposal to ban the life patents. Of late there is a revival of interest on this issue among some of the WTO Member sates and it may be translated into fresh proposals. Similarly, Article 71 also mandates a review of the implementation of the whole Agreement. These two reviews are also reflected in the Doha mandate. Second, there is also attempt to lock in more countries with TRIPS Plus commitments on the scope of patent protection and reduces their policy space. For instance, Japan Thailand FTA Article 130 states that “Each Party shall ensure that any patent application shall not be rejected solely on the grounds that the subject matter claimed in the application is related to a naturally occurring micro-organism”. This would make it difficult for Thailand to reject isolated genes from patent protection. Third, it is important to facilitate the actual use of TRIPS flexibilities in developing countries. In the absence of such effort developed countries would attempt to harmonise the patent examination procedures and virtually eliminate the policy space existing in law to deny patent on certain types of claims including genes. As shown above this is happening even in countries like India. One suggestion in this regard is to prepare a manual of patent examination on life form from a public interest angle analysing the various types of patent claims and its patentability under the existing TRIPS flexibilities. This would help many developing country patent offices to apply the flexibilities at the time of examination. Annex 1 no. Pat ent no. Applicatio n no. Title of Invention Name of the Patentee 213 698 216 702 216 568 213 110 214 298 218 538 993/MUM/ 2002 PROCESS FOR PRODUCING RECOMBINANT HUMAN SERUM ALBUMIN IN PICHIA PASTORIS BY A NOVEL GENE AND ITS PHARMACEUTICAL USES IN/PCT/200 BACTERIA 0/00216/D ATTENUATED BY A EL NON-REVERTING MUTATION IN EACH OF THE AROC, OMPF AND OMPC GENES, USEFUL AS VACCINES IN/PCT/200 A CHIMERIC GENE 1/00062/M COMPRISING A UM NUCLEIC ACID FRAGMENT CONFERRING DISEASE RESISTANCE TO PLANTS 466/CHENP TRANSCRIPTIONAL /2005 ACTIVATOR GENE FOR GENES INVOLVED IN COBALAMIN BIOSYNTHESIS 697/CHENP NOVEL SERINE /2003 PROTEASE GENES RELATED TO DPPIV CADILA HEALTHCARE LIMITED 01519/KOL NP/2004 UNIVERSITY OF TSUKUBA NOVEL ROOT KNOT NEMATODE RESISTANCE GENE AND APPLICATION THEREOF PEPTIDE THERAPEUTICS LIMITED E.I.DU PONT DE NEMOURS AND COMPANY GEYMONAT S.P.A. FERRING BV 219 556 01628/KOL NP/2003 VECTOR ENCODING HUMAN GLOBIN GENE AND USE THEREOF IN TREATMENT OF HEMOGLOBINOPA THIES CLONING AND SEQUENCING OF AGTSAL11 RICE GENE FROM IR-64 VARIETY IMPLICATED IN SALINITY STRESS TOLERANCE SLOAN KETTERING INSTITUTE FOR CANCER RESEARCH 022 72 997/MAS/1 999 20910 4 1074/DELNP/20 03 "A CHIMERIC CR3 GENE CONTAINING FRAGMENTS FROM DIFFERNT HIV-1 GENES" CENTRO DE INGENIERIA GENETICA Y BIOTECHNOLOGIA 21047 5 600/MUMNP/20 05 THE GENE CLUSTER INVOLVED IN SAFRACIN BIOSYNTHESIS AND ITS USES FOR GENETIC ENGINEERING PHARMA MAR S.A AVESTHA GENGRAINE TECHNOLOGIES PRIVATE LIMITED, AN INDIAN COMPANY