Coral reefs threats news articles

advertisement

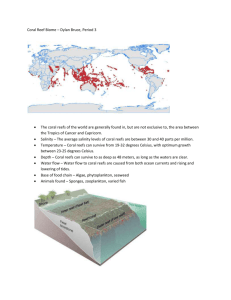

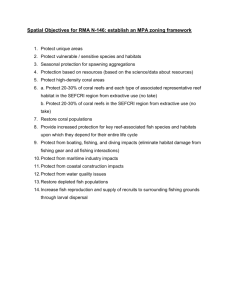

Human activity blamed for decline of coral reefs James Randerson The Guardian, Wednesday 9 January 2008 Caribbean coral reefs have suffered significant damage from over-fishing and run-off from agricultural land, according to a study of 322 sites across 13 countries. The study provides compelling evidence that proximity to a large human population spells bad news for the survival of reefs. "It is well acknowledged that coral reefs are declining worldwide but the driving forces remain hotly debated," said author Camilo Mora at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada. "In the Caribbean alone, these losses are endangering a large number of species, from corals to sharks." He estimates that the reefs provide $4bn in so-called ecosystem services - quantifiable benefits in terms of fishing, tourism and protecting the coast from storms. Numerous threats to coral reef ecosystems have been identified previously including overfishing, rising sea temperatures due to climate change, and pollution, but his team aimed to go beyond local effects and identify significant factors at a regional level. The study used data on the health of corals, fish and large algae such as seaweed from 322 sites between 1999 and 2001. The team then matched this with data on nearby coastal development, agricultural land use, environmental disasters such as hurricanes, and sea temperature. The results indicated that the number of people in close proximity to the reefs was the main factor governing declines in coral reefs. Coral death was further accelerated by warmer waters, the team reports in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. Temperature increases lead to coral bleaching in which the corals lose the symbiotic algae they need to survive. Acidic seas may kill 98% of world's reefs by 2050 Ian Sample, science correspondent The Guardian, Friday 14 December 2007 The majority of the world's coral reefs are in danger of being killed off by rising levels of greenhouse gases, scientists warned yesterday. Researchers from Britain, the US and Australia, working with teams from the UN and the World Bank, voiced their concerns after a study revealed 98% of the world's reef habitats are likely to become too acidic for corals to grow by 2050. The loss of big coral reefs would have a devastating effect on communities, many of which rely on fish and other marine life that shelter in the reefs. It would leave coastlines unprotected against storm surges and damage often-crucial income from tourism. Among the first victims of acidifying oceans will be Australia's Great Barrier Reef, the world's largest organic structure. The oceans absorb around a third of the 20bn tonnes of carbon dioxide produced each year by human activity. While the process helps to slow global warming by keeping the gas from the atmosphere, in sea water it dissolves to form carbonic acid - rising levels of which cause carbonates to dissolve. One of these minerals, aragonite, is used by corals and other marine organisms to grow their skeletons. It is particularly susceptible to carbonic acid. Without it, corals become brittle and are unable to grow and repair damage caused by fish, snails and natural erosion. The scientists used computer simulations to model levels of aragonite in the world's oceans from pre-industrial times, when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels stood at 280 parts per million. Present day levels of carbon dioxide are 380ppm, but scientists expect the figure will rise substantially by the end of the century. The team looked at three scenarios based on predictions of greenhouse gas emissions by the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The first assumed that atmospheric carbon dioxide was held at today's level, leading to an increase in temperature of 1C by the end of the century. Under this scenario there was enough aragonite left in the oceans for corals to continue growing. The second scenario looked at the effect of carbon dioxide levels at between 450 and 500ppm, a rise that would increase global temperatures by 2C. Under these conditions only very hardy corals and creatures that lived off them would survive. In the worst scenario, when carbon dioxide levels rose above 500ppm, the models predicted a 3C rise and a substantial increase in ocean acidity, causing the majority of reefs to die off. The study appears in the journal Science. "Before the industrial revolution over 98% of warm water coral reefs were bathed with open ocean waters 3.5 times supersaturated with aragonite, meaning that corals could easily extract it to build reefs," said Long Cao, a co-author from the Carnegie Institution in Stanford. "If atmospheric carbon dioxide stabilises at 550ppm, and even that would take concerted international effort, no existing coral reef will remain in such an environment." Peter Mumby, a reef ecologist at Exeter University, who worked on the study, said: " Reefs help protect coastlines from storm damage by acting as a buffer, so without them storm surges will go straight over and hit the coast." Under threat Philippines One of the most threatened coral hot spots, the reefs face damage from pollution, run-off from logging, and dynamite fishing Gulf of Guinea Around 20 sq km of reef between four islands off the west African coast under threat from coastal development and coral harvesting Sunda Islands Part of the coral triangle, one of the most diverse coastal areas. Already at threat from destructive fishing and reef fish trade Southern Mascarene Islands Reefs surrounding Mauritius, Reunion and Rodriguez islands in southern Indian Ocean are under threat from pollution from the sugar cane industry and agricultural development Eastern South Africa Next to Cape Floristic, this smaller reef is also at risk from over-fishing and tourism Environment Coral reefs are vanishing faster than rainforests 12:52 08 August 2007 by Catherine Brahic Coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific are disappearing twice as fast as tropical rainforests, say researchers. They have completed the first comprehensive survey of coral reefs in this region, which is home to 75% of the world's reefs. John Bruno and Elizabeth Selig of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the US compiled data from 6000 studies that between them tracked the fate of 2600 reefs in the Indo-Pacific between 1968 and 2004. They used the extent to which reefs were covered by live coral as an indication of their health. "The corals themselves build their limestone foundation, so if the surface of the reef is not covered with live tissue that is continually secreting it, the reef can erode fairly quickly," explains Selig. She and Bruno found that coral cover declined by 1% per year on average between 1968 and 2004. For comparison, tropical rainforests declined by 0.4% per year between 1990 and 1997 (Science, vol 297 p 999). Steep decline In the early 1980s about 40% of reefs were covered with live coral, but that number had halved by 2003. Today only 2% of Indo-Pacific reefs have the same amount of live coral as they did in the 1980s. That's much less than expected, says Selig. She explains that it was generally thought that Indo-Pacific reefs were faring much better than Caribbean reefs, a bias she believes stems from the fact that Caribbean reefs have been studied more extensively. Caribbean reefs are declining by 1.5% a year (Science vol 301p 929). The researchers found little difference between protected and unprotected reefs. "Well-managed reefs are definitely doing better in terms of fish population but not in terms of coral cover," Selig told New Scientist. This uniformity has led Selig and Bruno to conclude that warming seas as a result of climate change are likely to be driving the rapid decline. Warmer oceans cause coral bleaching because higher temperatures kill their symbiotic algae. They also help diseases spread across reefs. International effort Selig and Bruno say local policies - for instance to limit harmful fishing methods and reduce continental run-off - can do much to help maintain the corals in the short-term, but long-term conservation will require an international effort to tackle global warming. "There certainly are local problems that [reef] managers can and are addressing," says Bruno. "But there are problems that are happening at regional and global scales that no single manager, or even federal authority can cope with. Managers can't manage ocean temperatures." In 2004, research led by Andrew Baker of Columbia University in New York, US, suggested that coral reefs might adapt to live in warmer oceans (see Corals adapt to cope with global warming). Bruno says some reefs in their survey were recovering from previous damage - sometimes thanks to effective protection, sometimes independently of human intervention. But overall the reefs do not appear to be adapting fast enough to stem their decline. Baker believes more research is needed to explore whether anything can be done to boost corals' natural ability to adapt to change. "This might include attempts to inoculate the largest and oldest colonies on reefs with heat-tolerant symbiotic algae that might help them survive bleaching events," he says. Journal reference: PLoSONE (DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000711) Climate Change - Want to know more about global warming - the science, impacts and political debate? Visit our continually updated special report. Endangered species - Learn more about the conservation battle in our comprehensive special report. Coral cover across the Indo-Pacific region has declined by around 1% per year for the past four decades (Image: Bruno/Selig) Web address: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/10/ 071014201814.htm Fishing Ban Protects Largest Coral Reef In The Philippines enlarge Corals point into current flow. Swarms of anthias shelter near coral outcroppings and feed in the passing current. This photo was taken in a different coral reef area, near Fiji. (Credit: Copyright WWF - Canon/ Cat Holloway) ScienceDaily (Oct. 18, 2007) — Reef fish and other marine species can breathe easier with the introduction of a fishing ban around Apo Reef, the largest coral reef in the Philippines and the second largest contiguous reef in the world after the Great Barrier Reef. Under the ban, all extractive activities, such as fishing, and coral collection and harvesting, will be completely forbidden. “This ‘no-take’ zone will allow the reef and its residents ample time to recover from years of fishing,” stressed John Manul of WWF-Philippines. The 27,469-hectare Apo Reef off the coast of Mindoro Island is surrounded by mangrove forest, which serves as a source of food, nursery and spawning ground of several coastal fish and marine species, including sharks, manta rays, sperm whales and several sea turtles. In 1996, the reef was declared a national park, but enforcement proved lax and illegal fishing methods persisted. The park was once one of the world’s premier diving destinations, but years of fishing — including by unsustainable fishing practices such as using dynamite and cyanide — took its toll. “You would hear 25 to 30 dynamite blasts daily,” said Robert Duquil, a former protected area assistant superintendent. “The international diving community lost interest in the area and destructive activities prevailed.” Adding to the reef’s troubles, the El Niño phenomenon in 1998 raised ocean temperatures, prompting a massive bleaching episode and the death of countless corals, and an explosion of coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish. “Unfortunately, Apo is plagued by millions of these starfish, probably due to a lack of natural predators like the giant triton, napoleon wrasse and harlequin shrimp,” said Gregg Yan of WWFPhilippines. “We hope that the ban will ensure protection of these predators and the many other reef species.” WWF has been working towards sustainable coastal practices for the Apo Reef Natural Park since 2003. The marine park will be opened for tourists to help generate funds for its protection, as well as provide an alternative livelihood for hundreds of fishermen in the area. Email or share this story: | More Story Source: The above story is reprinted (with editorial adaptations by ScienceDaily staff) from materials provided by World Wildlife Fund.