2AC - openCaselist 2012-2013

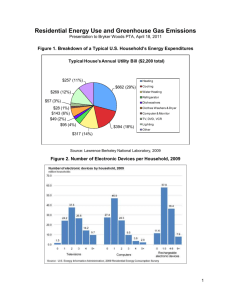

advertisement