Non-Operative Management of Solid Organ Injuries

advertisement

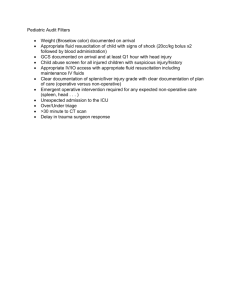

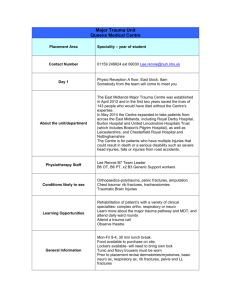

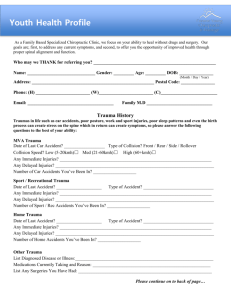

Non-Operative Management of Solid Organ Injuries Secondary to Blunt Abdominal Trauma: JRRMMC Experience January – March 2015 Alain Neil Ancheta, MD Introduction: Early in the twentieth century, abdominal trauma was associated with high mortality and a low threshold for laparotomy. A major change in the paradigm of the management of blunt abdominal trauma was the introduction of non-operative management. High rate of operative complications caused paradigm shift from operative to non-operative management in hemodynamically stable blunt abdominal trauma patients. This coincided with the widespread availability of CT scans and the introduction of angioembolisation as a common procedure for the management of solid organ injuries. Repeated clinical examination supplemented with modern imaging and laboratory investigations play a key role in reaching therapeutic decisions. Non-operative management can be safely practiced in a Trauma Care Centre which has trauma surgeons, newer imaging modalities, high dependency unit (HDU), ICU and other supporting services. In combination this shift has resulted in the reduction in the morbidity associated with laparotomy. Objectives: - To discuss the management of 5 cases of solid organ injury secondary to blunt abdominal injury To discuss the demographics, history, and course in the wards of the cases To discuss factors that terminate non-operative management Methods: This report will focus on the management of solid organ injuries in a tertiary hospital from January to March 2015. Patients with blunt abdominal injury without solid organ injuries are excluded from this report. There are a total of 5 patients admitted secondary to solid organ injury from blunt abdominal trauma. Results: Patient 1 Patient 2 Patient 3 Patient 4 Patient 5 Age 4 12 13 27 31 Sex Female Female Male Male Male Mechanism Vehicular Crash Vehicular Crash Vehicular Crash Vehicular Crash Fall Time from injury until initiation of Non-operative management 1hr 1hr 30 mins 30mins 24hrs 9hrs Initial vital signs Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Initial abdominal examination Tender Right Upper quadrant and epigastric area Tender left upper quadrant Tender left upper quadrant Tender right upper quadrant Tender left upper and left lower quadrant FAST Hepatorenal Hepatorenal Hepatorenal Hepatorenal Hepatorenal and splenorenal Liver injury none Grade II-III none Grade IV none Spleen injury Grade II none Grade IV (Intraop) none Grade II Other injuries Pneumothorax, Skull fracture, Diffuse Right Cerebral Axonal Injury Concussion None Radial Bone Fracture Factor(s) terminating nonoperative management N/A -Hypotension N/A N/A -Increasing heart rate -Decreasing blood pressure -Generalized Peritonitis -Decreasing Hemoglobin and Hematocrit count Total time until termination of nonoperative management N/A N/A 6hrs 6 days N/A Total Transfusion requirements 1 unit PRBC None 3 units PRBC 10 units PRBC None 13 units FWB 12 units PC 24 units FFP OR done None None Exploratory Laparotomy, Splenectomy Damage Control Surgery None Feeding started 4th HD 3rd HD 5th POD N/A 4th HD Morbidity None None Hospital acquired pneumonia N/A None Outcome Discharged Discharged Recuperrating Expired Dischaged Total Hospital Days 6 days 5 days N/A 5 days 6 days Discussion: Jose R. Reyes Memorial Medical Center is a 300 bed capacity hospital that caters to the indigent population of Metro Manila and all over Luzon. As the flagship hospital of DOH, it serves as one of the referral centers for trauma in the region. Trauma facilities include a surgical emergency room, a radiologic unit equipped with x-ray, ultrasound and Ct-scan, 4 emergency operating theaters and a 5 bed capacity surgical ICU for some of the critically ill trauma patients. The hospital, however, is far from perfect as monitoring equipment, advanced imaging and even man-power are still lacking. The hospital, though, adopts up-to-date guidelines and it is particularly challenging to individualize treatment of patients on available resources. The hospital still maintains as one of the best trauma centers in the Philippines. From January to March 2015, there are a total of 5 patients admitted due to solid organ injury secondary to blunt abdominal trauma. Three males and two females, age ranges from 4yrs old to 31yrs old with a mean age of 17yrs old. Modes of injuries are vehicular crashes (4/5) and fall (1/5). Current clinical practice guideline for blunt abdominal injury in JRRMMC is a follows: Stable Patient Surgery No Yes FAST Positive Negative Observe; treat other injuries Normotensive Hypotensive CT scan with triple contrast or DPL Surgery (+) CT scan for hollow viscus organ, (+) DPL (excluding blood) (-) DPL, (-)CT scan for hollow viscus organ injury Surgery Non-operative management Before going into the non-operative management, what are the risks and costs of directly operating on a patient? Trauma literature describes a category of laparotomies that reveal no pathologic findings and are termed ‘nontherapeutic’. Nontherapeutic laparotomy is also defined by some as a laparotomy for a minor injury that, in retrospect, required no surgical treatment. Nontherapeutic laparotomies are associated with significant morbidity and costs. The reported incidence of laparotomy or anesthesiarelated early complications varies between 8.6% and 25.6%. Both overall cost and hospital stay for patients undergoing NTL are also significantly greater than for patients successfully managed nonoperatively. In one study, the mean hospital charges for patients with abdominal gunshot wounds successfully managed non-operatively were nearly $10,000 less than those for patients with unnecessary operations. It is partly because of this experience that the trauma surgeon’s scope of practice has shifted toward selective nonoperative management of an entire spectrum of injuries. While starting non-operative management, certain principles have to be applied. The trauma surgeon should maintain high index of clinical suspicion; Always keep the mechanism of injury in mind; Patient should be examinable, with clear mental status; Patient should be hemodynamically stable, with no obvious operative indications; Be cautious when committing to nonoperative management in multiply injured patients ; Adequate healthcare team resources must be available (ability to perform frequent physical exams, re-imaging, repeat laboratory); Appropriate setting for nonoperative observation is available (observation ward, intensive care unit, monitored emergency department bed); Operative management should be available and instituted promptly if indicated by signs/symptoms. Upon arrival at the emergency room, time from injury to start of consult and/or non-operative management range; 30mins,1hr, 1hr 30mins, 9hrs, 24hrs. Patients were examined, initial vital signs taken, appropriate ancillaries and imaging requested and other injuries identified. Most of the samples are polytrauma patients involving Neurosurgical service 2/5 (Skull fracture with cerebral concussion, diffuse axonal injury), Orthopedic service 1/5 (radial bone fracture) and Thoracic service 1/5 (pneumothorax). Only 1 patient had an isolated blunt abdominal injury. All patients were FAST positive requiring further investigation with CT-scan (4 out of 5). Solid organ injuries involved are liver 2/5 and spleen 3/5. Liver injuries range from grade 3 and grade 4-5 while splenic injuries are grade 2, grade 2 and grade 4. These represent the most commonly injured solid organs after blunt abdominal trauma. Overall success rates of non-operative management of above solid organ injuries are 80% and 80-90% respectively. However factors such as age, increasing transfusion requirements, high injury grade, physiological deterioration, worsening abdominal examination, multiple intrabdomoninal injuries, unexplained fever or leukocytocsis, hollow viscous signs on CT abdomen are predictors of failure of nonoperative management. Non-operative management of the pediatric splenic injuries are generally excellent as they have a low incidence of delayed bleeding. This is attributable to the relative thickness of the splenic capsule, perhaps conferring more structural integrity. The spleen in children is more likely to fracture parallel to the splenic arterial blood supply rather than transverse to it. Published literatures have shown that radiological grade of severity of injury is not a contraindication for non-operative management. However, severe solid organ injury may dramatically affect the success rate of nonoperative management. Data above shows, 2 out of 5 patients failed non-operative management, both of them having Grade 4 solid organ injuries. Studies show success rates drop to 67% for grade IV and 25% for grade V splenic injuries. In another study 14% of grade IV and 22.6% of grade V liver injuries fail non-operative management. This was substantially higher than the 3-7.5% failure rate of more minor liver injuries. Patient 3 had no progression of the abdominal status but had increasing heart rate and decreasing blood pressure. On a patient with decreased neurologic status and deteriorating vital signs, a decision was made to terminate non-operative management on the 6th hour. In a review by S. P. Stawicki, patients for whom clinical examination is not reliable, special investigations can be crucial in early and accurate triage. Lack of reliable physical examination may constitute a relative contraindication to non-operative management of traumatic injuries in patients who fall into this ‘indeterminate’ zone. It would be prudent to pay attention in changes in vital signs and examination findings; as such a clear indication for laparotomy (generalized peritonitis or hypotension) may be seen too late. Intra-op findings showed 1 liter hemoperitoneum and a grade 4 splenic injury. The patient subsequently underwent splenectomy. The patient was fed on the 5th post-op day via naso-gastric tube and is still recuperating from his head injury. Patient 4 was successfully managed non-operatively until on the 6th day, the patient presented with generalized tenderness and hypotension, a sign of delayed hemorrhage. Delayed hemorrhage after nonoperative management is a feared complication. A study suggested an overall incidence of 0-14% without angioembolization. The patient underwent damage control surgery but eventually expired due to multi-organ failure. In retrospect an alternative to surgical management in this setting would have been angioembolization. In one study of hemodynamically unstable high grade solid organ injury patients a survival rate of 86% after angioembolization and resucitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta was reported. All of the lower grade solid organ injuries (3/3) were successfully managed non-operatively. Up to this day, there are no clear guidelines enumerating the end-points of non-operative management. In our setting, feeding was started when patient had no complaints of abdominal pain, vital signs were stable, non-tender abdomen on palpation and when there is no proximate indication for immediate operation. It would be safe to make tolerance of feeding as one of the end-points of safely discharging a patient from ICU or the ward. As above all patients (3/3) who were managed non-operatively and tolerated feeding were discharged successfully without complications. Overall, patients managed non-operatively had lesser transfusion requirements, resumed feeding earlier, had no reported morbidities, and had shorter hospital stay. However, caution must be used in interpreting these results as the patients who failed non-operative management had more severe illnesses. Conclusion: Non-operative management of grades I-III liver and spleen injuries can be safely practiced in our setting. However care must be taken in managing higher grades, with vigilant monitoring and more frequent reassessments. It is better to bring the patient in the OR while normotensive if angioembolization is not available.