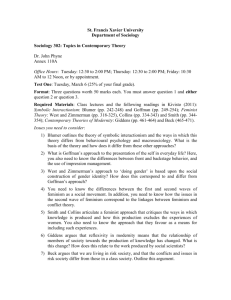

Course Proposal: Women and Social Change in the Arab Gulf

advertisement

Women and Social Change in the Middle East Spring 2012 Instructor: Office: Office Hours: Email: Course Schedule: Course Location: Dalia Abdelhady Finngatan 16 Room no. 302 Tuesday 14:00-15:00 and by appointment dalia.abdelhady@cme.lu.se March 24 – May 28 Monday & Wednesday 13:00-14:45 Finngatan 16, seminar room COURSE DESCRIPTION The key drivers of social change in the Middle East are traditionally considered to be economic development and modernization of the state. For the last two decades, ruling elites of Middle Eastern countries have implemented liberalization policies in an attempt to foster economic growth, and women in the region have benefitted in numerous ways from such policies. The state has played an important role in facilitating women’s access to education, employment, economic opportunities, leadership positions and general participation in public life. Economic liberalization also granted women’s access to markets and motivated many to start or expand their private businesses. However, despite these changes in women’s lives, in many countries in the Middle East women’s participation in collective forms of action has at times aimed at changing governmental policies towards women, or aimed at challenging social gender norms altogether. This course addresses the role of women in promoting social change in the contemporary Middle East with a primary focus on the interaction between women’s activism and state actors. We will start with a general overview that contextualizes the role of women in Middle Eastern society within historical and theoretical contexts. We will then interrogate specific processes of change in the economic, political and cultural spheres. In doing so, we will discuss specific forms of social change that women have brought about in society and focus on contemporary movements to promote social change further. Special attention will be given to the role of both the global context and local national traditions in shaping the role of women’s activism in contemporary Middle Eastern Society. Learning Outcomes Upon finishing the course, students would be expected to: describe different processes of social change and their impact on women in the presentday Middle East; illustrate, analyse and assess the role of women in guiding specific forms of social change in the contemporary Middle East; 1 assess opportunities and obstacles promoting or challenging gender equality in the Middle East; evaluate the role of local traditions and cultures in enhancing or limiting the role of women in social change in the Middle East; and evaluate the role of globalization in affecting the role of women in social change in the Middle East. COURSE REQUIREMENTS The course requires readings, class participation and several written assignments. In addition to these requirements, students are also expected to present a term paper in class and in writing. The grade distribution is as follows: Class Attendance and Participation Daily Reflection Essays Final Paper (paper and in-class presentation) 25 percent 50 percent 25 percent Class Attendance and Participation Students are expected to keep up with reading assignments and think about the readings critically before they come to class. Informed participation is expected from all students and there will be various opportunities for discussion to ensure that all students have a chance to participate. While first-hand experiences and personal opinions are often welcome, students are expected to focus their class participation on analytical insights and theoretical details to construct their arguments. To obtain full credit for attendance and participation a student should: Attend all class meetings Read all course material before coming to class Discuss the readings during class Integrate arguments across readings Answer questions presented by the instructor and other students Ask questions relating to readings or comments that are presented by other students Lead class discussion during at least one class session Visit during office hours to clarify ideas Offer questions or comments via email While in class please follow these common courtesy rules: Turn off cell-phones (and don’t just put them on vibrate) Laptops and other electronic devices are not acceptable for use during class Show up to class on time Stay alert in class Refrain from disruptive behavior 2 Since students’ involvement is required in almost every class meeting, attendance records will be kept for each class. Missing more than two classes will reduce your grade by one full letter. Missing more than four classes will result in your failure, regardless of your performance in the other requirements. Daily Reflections To facilitate class discussion and participation, students are expected to submit a total of TEN reflection essays before class readings are due, and each will be worth 5 points. The essay should focus on the set of reading to be discussed in class for that day. The essay should be a brief discussion of what you believe to be the most important argument of the readings. Your reflection should focus on the ways the main arguments raised by the authors relate to (or explain) the conditions of women in the Middle East and the main aspects of social change that they are engaged in. Each reflection essay should also discuss the ways the authors’ argument informs future research by posing possible research questions that relate to the topic. I will evaluate your reflection statements based on the following rubric:1 Exceeds Expectations (5 points) Meets Expectations (3 points) Fails to meet expectations (1 point) Identification You identified the main arguments and the important concepts used to make it. You identified a concept and provided a comprehensive definition. You did not identify or define a concept from the reading. Significance You placed the argument within the general field of Middle East Studies, and your own views and empirical applications. You used comparisons with other authors to make your point. You creatively highlighted the ways the argument can be used in future research. You expressed the practical and theoretical significance of the argument. You failed to mention the significance of the argument. Technical exposition Your statement is well organized and interesting. Adequate organization and flow of statement. Incomprehensible organization, stylistic problems and lacks coherence. 1 The two grading rubrics were developed from material from Dr. Lisa Brush at the University of Pittsburgh and adopted with permission. 3 Final Paper and Presentation A 3500-word paper is required for this course, which is due on June 9th. You should choose one of two options for the topic of your paper: Option One: A research proposal that outlines the study of a topic related to those discussed in class. The proposal should consist of a clearly-stated research question, literature review, research justification, methodology and strategies for data collection. Ideally, this proposal will be similar to the one you are required to submit to your thesis advisor later in June. Option Two: An analysis of a case study of a form of women’s collective action in the Middle East. Your paper should highlight the historical background, specific goals and strategies, and organizational aspects to your case study. You should also analyze the case study within the context of the various arguments or case studies discussed in class. If you take this option, you will need to make sure that your paper provides more than a descriptive summary of the case study, in the form of an analytical/critical argument. Students should think of the term paper as an enjoyable exercise that allows them to explore a topic of their interest as well as demonstrate their analytical skills. Term papers will be evaluated based on your ability to demonstrate the following steps: Think about the topic you choose. o The topic needs to move beyond descriptive analysis and focus on a question, puzzle or problematic. Pick literature that is most relevant to that topic. o Use at least three readings from the class. Find references in the library that supplement class readings. o Be extensive but also pay attention to finding relevant ones that relate directly to your topic. Formulate an argument that the paper addresses based on your sources. o Your paper should be based on a clear thesis statement that reflects the organization of your thoughts in a logical way that develops throughout the paper. o If you’re working on a research proposal, make sure that your research question is succinct and that everything you include in your proposal is relevant to it. Summarize the arguments in the various readings and use these summaries to formulate the outline for the paper. o Your thesis statement and outline will probably change over time, but they keep you focused when it is time to write. 4 Follow the outline to elaborate the arguments of the different authors in a clear manner. Build your literature review in an interesting way. o And make sure that you are connecting it to your thesis statement. Make sure that the paper provides a single focused line of argument, and includes an introduction and a conclusion. o Your thesis should indicate a clear purpose for the paper and should be established in the introduction, developed logically and fully throughout the paper, and summarized and clearly articulated in the conclusion. Reference all sources used in the paper both within the body of the paper and in a Works Cited page. Use the Chicago Manual of Style. The deadline for the optional draft is May 28th Students should keep in mind some basics of writing good papers: Support your claims. Make an argument instead of unsupported assertions. Focus on analytical insights instead of opinions. Connect ideas, sentences and paragraphs. Make sure that your writing flows and that sentences are well constructed to show how ideas relate. Write simply. DO NOT use Google or Wikipedia (Google Scholar is OK). Use course material, academic journals (obtained through databases) and scholarly books. I will evaluate the term paper based on the following rubric: Exceeds expectations (20 points) Meets expectations (15 points) Fails to meet expectations (10 points) General Structure Thesis statement well stated. Literature well chosen for topic. All relevant concepts are discussed. Clear thesis. Literature well chosen for topic. Some concepts are discussed. No clear thesis statement. Discussed concepts are not applicable to topic. Content Uses topic to apply knowledge of the Middle East. Identifies similarities and differences between different approaches. Clear connections between paper topic and the field. Identifies some of the main agreements and disagreements in the literature. Fails to apply knowledge of the field to paper topic. Fails to identify similarities and differences. Fails to draw conclusions or integrate personal opinion to argument. 5 Exceeds expectations (20 points) Meets expectations (15 points) Draws thoughtful conclusions from the literature review. Integrates personal opinion with material thoughtfully. Summarizes implications of the topic to Middle Eastern Studies. Attempts to make conclusions but with some difficulty explaining the significance of these conclusions. Integration of personal opinion is incomplete. Organization and Development Thesis is established in the introduction, is fully developed throughout the paper, and a reasonable conclusion is articulated. Strong connections of ideas and transitions through the paper that facilitate understanding. Thesis reflects the purpose of the paper. Introduction and conclusion are present but may be incompletely developed. Makes coherent connections between sentences. Uses transitions between paragraphs and within them. Conventions and editing Accurate and consistent Accurate and citations. consistent citations. Writing flows and Thoughtful writing, contains wellbut not always constructed sentences effective. that show relations Occasional use of between ideas. awkward sentences. Precise sentence-level editing. Fails to meet expectations (10 points) No main idea. Ineffective introduction and/or conclusion. Connections between ideas are confusing or not present. Improper citations, phrasing interferes with reader understanding, no editing apparent. GENERAL GUIDELINES Dishonesty I am quite confident that no one in this class would violate academic conventions regarding dishonesty. However, it is my duty to inform you that any student who breaks the rules by 6 cheating, plagiarizing, or falsifying records will receive a failing grade for the course and have the case reported to the University administration. Religious Observance Religiously observant students wishing to be absent on holidays that require missing class should notify me in writing at the beginning of the semester, and should discuss, in advance, acceptable ways of making up any work missed because of the absence. Disability Accommodations Students needing academic accommodations for a disability must first contact the MA Program Coordinator, Professor Torsten Janson, to verify the disability and to establish eligibility for accommodations. GRADES Grades will be granted based on the following scale: A = 94+ B+ = 87-89 C+ = 77-79 D+ = 67-69 A- = 90-93 B= 84-86 C = 74-76 D = 64-66 B- = 80-83 C- = 70-73 D- = 60-63 F = 59> About the Grading Scale A: Outstanding work that goes above and beyond the requirements of the assignment and demonstrates exceptional critical skills and creativity. Outstanding effort, significant achievement, and mastery of the material of the course are clearly evident. B: Above Average work that demonstrates a thorough understanding of the course material, fulfills all aspects of the assignment and goes a bit beyond minimum competence to extra effort, extra achievement or extra improvement. C: Average work that fulfills ALL aspects of the assignment with satisfactory understanding of course material. If you do the assignment exactly as it is assigned, you will receive an average grade (75%). D: Below Average work that shows a marginal understanding of the material but also failure to follow instructions, implement specific recommendations or demonstrate personal effort. F: Failure to follow instructions for an assignment and lack of demonstration of basic course material. COURSE READINGS Part One: General Context March 24 Introduction to class 7 March 26 March 31 April 2 Lila Abu Lughod (2010). The Active Social Life of "Muslim Women's Rights": A Plea for Ethnography, Not Polemic, with Cases from Egypt and Palestine. Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, 6 (1): 1-45 Shadi Hamid (2006). Between Orientalism and Postmodernism: The Changing Nature of Western Feminist Thought Towards the Middle East. Hawwa, 4 (1): 76-92. The Meaning of Social Change Asef Bayat (2007). A Women’s Non-Movement: What it Means to be a Woman Activist in an Islamic State. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 27 (1): 160-172. Pinar Ilkkaracan (2002). Women, Sexuality and Social Change in the Middle East and the Maghreb. Social Research, 69 (3): 753-779. Sunny Daly (2010). Young Women as Activists in Contemporary Egypt: Anxiety, Leadership, and the Next Generation. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 6 (2): 59-85. Deniz Kandiyoti (1988). Bargaining with Patriarchy. Gender and Society, 2 (3): 274-290. The Interplay Between Global and Local Contexts Nayareh Tohidi (2002). The Global-Local Intersection of Feminism in Muslim Societies: The Cases of Iran and Azerbaijan. Social Research, 69 (3): 851-887. Hoda Yousef (2011). Malak Hifni Nasif: Negotiations of a Feminist Agenda Between the European and the Colonial. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 7 (1): 70-89. Pinar Ilkkaracan (2008). Introduction: Sexuality as a Contested Political Domain in the Middle East. In Pinar Ilkkaracan (Ed.). Deconstructing Sexuality in the Middle East (pp. 1-16). Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing. Mervat Hatem (2006). In the Eye of the Storm: Islamic Societies and Muslim Women in Globalization Discourses. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 26(1): 22-35. Historical Context in the Middle East 8 April 7 Sarah Graham Brown (2001). Women’s Activism in the Middle East: A Historical Perspective. In Suad Joseph and Susan Slyomovics (Eds.). Women and Power in the Middle East (pp. 23-33). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Pernille Arenfeldt and Nawar Al-Hassan Golley (2012). Mapping Arab Women's Movements: A Century of Transformations from Within. Oxford University Press. Women and Development Fida J. Adely (2009). Educating Women for Development: The Arab Human Development Report 2005 and the Problem with Women’s Choices. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 41: 105-122. F. Umut Bespinar (2010). Questioning Agency and Empowerment: Women’s Work-Related Strategies and Social Class in Urban Turkey. Women’s Studies International Forum, 33: 523-532. Mervat Hatem (1994). Egyptian Discourses on Gender and Political Liberalization: Do the Secularist and the Islamist Views Really Differ? Middle East Journal, (Autumn 1994), pp. 661-676. Michael Ross (2008). Oil, Islam and Women. American Political Science Review 102: 107-123. Valentine Moghadam (2005). Women’s Economic Participation in the Middle East: What Difference has the Neoliberal Policy Turn Made? Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 1 (1): 110-146. Marie Duboc, “Where are the Men? Here are the Men and the Women! Surveillance, Gender and Strikes in Egyptian Textile Factories”, JMEWS: Journal of Middle East Women Studies 9, 3 (2013), pp. 28-53. April 9 Film: 678 Part Two: Feminisms April 23 Arab Feminism Marina Lazreg (2013). Poststructuralist Theory and Women in the Middle East: Going in Circles. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 6 (1): 74-81. Kaitham Al-Ghanim (2013). The Intellectual Framework and Theoretical Limits of Arab Feminist Thought. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 6: 82-90. 9 April 28 April 30 Mervat Hatem (2013). What Do Women Want? A Critical Mapping of Future Directions for Arab Feminisms. Contemporary Arab Affairs 6 (1): 91-101. Amal Grami (2013). Islamic Feminism: A New Feminist Movement or a Strategy by Women for Acquiring Rights? Contemporary Arab Affairs, 6: 102-113. Islamic Feminisms Valentine Moghadam, “Islamic Feminism and its Discontents: Towards a Resolution of the Debate” Signs 27, 4: pp. 1135-1171. Omaima Abou-Bakr, Feminist and Islamic Perspectives: New Horizons of Knowledge and Reform (Cairo: Women and Memory Forum, 2013): Margot Badran (2005). Between Secular and Islamic Feminism/s: Reflections on the Middle East and Beyond. Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, 1 (1): 6-28. Lila Abu-Lughod (1998). The Marriage of Feminism and Islamism in Egypt: Selective Repudiation as a Dynamic of Postcolonial Cultural Politics. In Lila Abu-Lughod (Ed.). Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East (pp. 243-269). Princeton: Princeton University Press. Islamic Feminism cont. Islah Jad (2011). Islamist Women of Hamas: Between Feminism and Nationalism. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 12 (2): 176-201. Sherine Hafez (2011). An Islam of Her Own: Reconsidering Religion and Secularism in Women’s Islamic Movements. New York: New York University Press, pp. 51-162. Asma Barlas (2005). Globalizing Equality: Muslim Women Theology and Feminism. In Elizabeth Fernea (Ed.). On Shifting Grounds, (pp. 91-110). New York: The Feminist Press. Margot Badran (2009). Feminism in Islam: Secular and Religious Convergences. Oneworld. Chapters 6 and 8. May 5 Film: The Light in Her Eyes May 7 no class May 12 Liberal Feminisms 10 May 14 Cathlyn Mariscotti (2008). Gender and Class in the Egyptian Women’s Movement, 1925-39. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. Nadje Al-Ali (2000). Secularism, Gender and the State in the Middle East, the Egyptian Women’s Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rabab Abdel Hadi, “Palestinian Women’s Autonomous Movement: Emergence, Dynamics and Challenges”, Gender and Society 12, 6: 649-673. Nadje al-Ali and Nicola Pratt, “The Iraqi Women’s Movement”, Feminist Review 88 (2008): pp. 74-85. State Feminisms Mounira Charrad, States of Women’s Rights: The Making of Postcolonial Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. Mervat Hatem, “In the Shadow of the State: Changing Definitions of Arab Women’s Developmental Citizenship Rights”, JMEWS: Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies (Fall 2005). Mervat Hatem, “Egypt’s Economic and Political Liberalization and the Decline of State Feminism”, International Journal of Middle East Studies (May 1992). Part Three: Women and Collective Action May 19 Women and Civil Society Organizations Mariz Tadros (2010). Between the Elusive and the Illusionary: Donors’ Empowerment Agendas in the Middle East Perspective. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 30: 224-237. Islah Jad (2009). The NGO-isation of Arab Women’s Movement. IDS Bulletin, 35 (4): 34-42. R. T. Antoun (2000) Civil Society, Tribal Process, and Change in Jordan: An Anthropological View, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 32: 441463 Lubna Al-Kazi (2011). Women and Non-Governmental Organization in Kuwait: A Platform for Human Resource Development and Social Change. Human Resource Development International, 14 (2): 167-181. 11 May 21 D. Singerman (2005). Restoring the Family to Civil Society. Lessons from Egypt, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 2 (1):1-32 A Public Sphere for Women Amelie Le Renard (forthcoming). Women’s Movements and Non-Movements in Saudi Arabia Transgressing Rules or Claiming Rights? Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies. Fatima Sadiqi and Moha Ennaji (2006). The Feminization of Public Space: Women’s Activism, the Family Law, and Social Change in Morocco. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 2 (2): 86-114. Stacey Philbrick Yadav (2010). Segmented Publics and Islamist Women in Yemen: Rethinking Space and Activism. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 6 (2): 1-30. Suad Joseph (1997). The Public/Private: The Imagined Boundary in the Imagined Nation/State/Community: The Lebanese Case. Feminist Review, 57: 73-92. L. Abu-Lughod (2005). On and Off Camera in Egyptian Soap Operas: Women. Television, and the Public Sphere. In F. Nouraie-Simone (ed.) On Shifting Ground: Muslim Women in the Global Area (pp. 17-35). NY: the Feminist Press. May 21 Film: Kalam Nawaem May 26 Women’s Counterpublics Loubna Skalli (2006). Communicating Gender in the Public Sphere: Women and Information Technologies in the MENA. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 2 (2): 35-59. Dina Matar (2007). Heya TV: A Feminist Counterpublic for Arab Women? Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 23 (3): 513524. Hoda Elsadda (2010). Arab Women Bloggers: The Emergence of Literary Counterpublics. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communications, 3: 312332. F. Mernissi (2005). The Satellite, the Prince, and Scheherazade: Women as Communicators in Digital Islam. In Fereshteh Nouraie-Simone (ed.) On 12 Shifting Ground: Muslim Women in the Global Era (pp. 3-16). New York: Feminist Press. May 28 The Arab Uprisings Dina Shehata, “Youth Movements and the 25 January Revolution”, in Arab Spring in Egypt (pp. 105-124). Vickie Langohr, “This is Our Square”: Fighting Sexual Assault at Cairo Protests”, Middle East Report, 268 (Fall 2013), pp. 18-26. Paul Amar, “Middle East Masculinity Studies: Discourses of “Men in Crisis” Industries of Gender in Revolutions”, JMEWS: Journal of Middle East Women Studies 7, 3 (Fall 2011): 36-70. Hania Sholkamy, “Women Are Also Part of this Revolution”, Arab Spring in Egypt (pp. 153 174). Mervat Hatem, “Gender and Revolution in Egypt”, Middle East Report, no. 261 (Winter 2011), pp. 36-41. Diane Singerman, “Youth, Gender and Dignity in the Egyptian Uprising”, JMEW:Journal of Middle East Women Studies 9, 3 (2013), pp. 1-27. Mervat Hatem, “Gender and Counterrevolution in Egypt”, Middle East Report, no. (Winter 2013), pp. 13