2015 September/October Topic Briefs .DOC

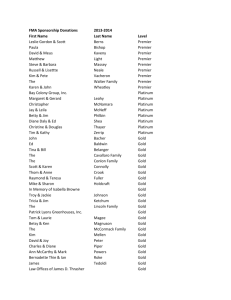

advertisement