MPhil_Handbook2015-16 (3)_Final

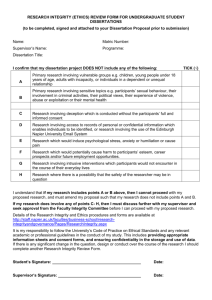

advertisement