Review of the potential for urban gardens to aid conservation efforts

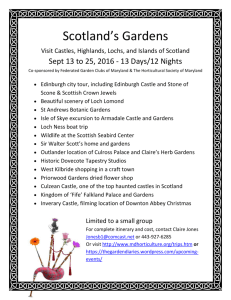

advertisement

Matthew Nash A critical review of the potential suitability of residential gardens in the UK as a conservation tool for four contrasting taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, insects and plants Matthew Nash INTRODUCTION Over the last 50 years, the UK population has increased by 18.7% and the rate of this population growth has been increasing (ONS 2014). To accommodate for the rising population, more of the UK landscape must be converted into households. As a result of the increasing population and house numbers, the UK landscape is becoming increasingly urbanised. The UK definition of an urban area is a built up area that has a resident population of over 10,000 inhabitants (Defra 2014). Figure 1 shows the population distribution across rural and urban areas in England in 2009, the large majority of the population are shown to now reside in urban areas. Urbanization is a global trend, urban areas were estimated to cover 4% of the total global land cover in 2000 (UNDP et al. 2000). The fact that an increasing proportion of land area is becoming urbanised means that an increasing proportion of green spaces available for wildlife are in the form of residential gardens. A study which took samples of 250 randomly selected dwellings in the UK found that 87% had gardens (Gaston et al. 2005). This means that although residential gardens are typically small, due to their large numbers they make up a significant amount of green space in urban areas. Residential gardens compose between 35-47% of urban green space which is a large proportion of the available habitats for animals (Loram et al. 2007). The management of these gardens can therefore be expected to have potential as a conservation tool for wildlife in urban areas due to their combined size. It is estimated that 82% of the UK population now live in urban areas and this high proportion of the population living in urbanized areas has implications on local wildlife (The World Bank Group 2014). Due to the fact that urban areas contain a large number of buildings, they contain less green space than the other areas in the UK. The lack of vegetation can detrimentally affect species of animals and birds who are dependent upon the species richness of vegetation in the area (Mckinney 2008). The management of the many residential gardens which, in total, compose a large proportion of urban green space could be a useful tool in mitigating the negative effects of urbanisation on wildlife. Using residential gardens as a conservation tool seems to be an increasingly relevant idea as the expansion of urban areas is a trend which is set to continue (Liu et al. 2003). Figure 1. Population figures for England by Rural/Urban area type. (Reproduced from ONS 2014) Matthew Nash PLANT CONSERVATION Since domestic gardens make up a large proportion of green space in urban areas, the choices of which plant species are present in these areas can have effects on local ecosystem functions. Urbanization is a primary cause of extinction for plant species and due to the expansion of urban areas it is important to focus on what makes some plants survive in urban areas while others don’t (Duncan and Young 2000). The most abundant plant species in UK urban gardens are weedy natives, particularly herbaceous perennial species (Thompson et al. 2005). This may be expected from their ability to become established quickly and their characteristic fast growth. The providence of habitat and forage by herbaceous plants is largely seasonal as they die back in the winter. The majority of plant species in urban gardens are alien species, one study found that of the total 1166 species present in the surveyed gardens, 70% were alien, however alien species were present in much smaller numbers (Smith et al. 2006). Plant conservation efforts are commonly associated with the protection of native plant species since natives are known to provide greater benefits to native animal species than alien species (Corbet et al. 2001). Non –native species can have negative effects on native plant species through competition and habitat modification (Manchester and Bullock 2000). The negative impacts of alien species are listed as one of the primary threats to global biodiversity (IUCN 2000). Research has found urban gardens to have similar levels of diversity to rural areas and has found them to in fact be less homogenous despite the common feature of garden lawns (Thompson et al. 2003). However, the larger proportion of alien species in urban areas may mean that despite the similar level of diversity the plant species do not interact as well as assemblages found naturally. There are worries that some invasive species such as the Spanish bluebell Hyacinthoides hispanica, can out compete and hybridize with native population and this can endanger them (RHS 2014). Urban gardens near woodlands with native populations can help mitigate this problem by not growing Spanish bluebells and by removing them if they are present in these gardens. Humans have the predominant influence on what plant species are present in their gardens and can alter the composition with relative ease. Urban gardens therefore have huge potential to aid plant conservation efforts as long as owners are motivated and educated to view gardens from an ecological perspective. INSECT CONSERVATION The conservation of insects within urban gardens is a topic which may not be as warmly welcomed by the public as other conservation projects and therefore may be harder to achieve. This may be due to the common view of insects as unwelcome pests despite the fact that only a very small proportion of insects are pests (Speight et al. 2008). Insects are the main group of pollinators and therefore provide essential ecosystem services (Kremen et al. 2007). There has been a recent decline in the numbers of the European honey bee Apis melifera which is a key pollinating species and this has raised conservation concerns (Biesmeijer et al. 2006). Conservations of bees in urban areas is an important issue because the species richness of bees has been found to decrease with urbanization, although some species are aided by the availability specialist habitat features in urban areas (Bates et al. 2011). It has however, been found that abundance of bees is more strongly linked to the availability and diversity of flowers than the intensity of urbanization (Kearns and Oliveras 2009). This means that careful management of residential gardens to ensure that there is Matthew Nash diverse flower forage across urban areas could be a useful conservation tool. Bee abundance is greater on non-native plant species than native species (Matteson 2007). It may therefore increase the efficacy of bee conservation efforts to focus upon increasing the abundance of non-native plant species in urban gardens however general biodiversity tends to be supported best by native species (Smith et al. 2006). It has been proposed that residential gardens primarily support generalist insect species which do not rely on specific plant species as food sources. Garden butterflies are typically generalist and this is because the variable nature of species composition across residential gardens is not such a trouble for generalist species who have a wider range of food sources (Bergerot et al. 2010). This, to some extent, brings into question the conservation value of gardens. The generalist species, which have been found to be the most common visitors, would have a better chance of finding food without urban gardens than the specialist species which are currently benefitting from urban gardens to a lesser extent (Goulson et al. 2006). Research has also found that the diversity of native butterfly species decreases towards urban centres whilst the opposite pattern is apparent in non-native species (Mckinney 2002). It may then increase conservation efforts for butterfly species if urban gardens in near urban centres aimed to support native butterflies with appropriate flora composition as they are most affected in these areas. BIRD CONSERVATION The impacts of urbanization on birds, such as habitat fragmentation, may be expected to be felt to a lesser extent than in other taxonomic groups due to their aerial mobility. Some research has in fact found a positive relationship between species richness and urbanization. However, these results are largely attributed to the presence of urban exploiters who are aided by features associated with urbanization such as the availability of garbage (Chace and Walsh 2006). Research focusing on the abundance of birds along a gradient of increasing urbanization found that some bird species decreased in abundance as urbanization increased whilst other species were less affected (Bolger et al. 1997). A study which looked at what makes certain species successful in urban habitats found that a combination of traits are necessary, including diet and preferred nesting sites (Banker et al. 2007). By analysing the available information on what makes bird species particularly adaptable or vulnerable to the effects of urbanization, educated methods for conservation efforts can be put into place. There is data that suggests that bird diversity is positively correlated with the number of adult trees and the presence of heterogenic plant layers (Mason et al. 2007). A study investigating the relationship between tree availability and bird diversity found a positive correlation between the amount of tree cover and bird diversity in urban areas (Paker et al. 2014). This study also found that native birds preferred to forage on native trees whilst alien birds preferred alien trees. The implications of these finding can be applied to conservation efforts when trying to protect particular species as well as in broader efforts. Owners of urban gardens can plant either native or non-native tree species in order to provide forage and nesting sites for certain bird species known to visit the trees. Diversity of bird species is supported by complex vegetation structure, there tend to be more bird species in areas with the most complex vegetation (Sandstrom et al. 2006). This finding suggests that if urban gardens are used for conservation goals, creating heterogeneous gardens with both trees and shrubs would be likely to support the largest number of bird Matthew Nash species. However as some urban gardens are only small areas, it may not be possible for some household owners to own trees due to their size. This may be a contributing factor to the lack of suitable nesting sites for some species in urban areas. Birds in particular benefit from involvement in wildlife gardening as well as the presence of gardens as green spaces. It is estimated that in the UK, 12.6 million households provide supplementary feeding for birds and that urban gardens provide at least 4.7 million nest boxes (Davies et al. 2009). The presence of bird feeders in urban gardens has been found to have a positive effect of the abundance of birds on a regional scale (Fuller et al. 2005). MAMMAL CONSERVATION Mammals in urban areas can be affected by a variety of factors associated with urban living. They face challenges such as the mortality risks posed by roads and traffic and the barrier effects caused by roads which impede the movement of urban animals (Rondinini and Doncaster 2002). However some factors associated with urban areas can be beneficial such as the presence of food subsidies (Saito and Koike 2013). Small mammals have been found to be affected by urban disturbance and a lack of vegetation density which is typical in urban areas (Dickman and Doncaster 1987). Domestic gardens which provide greater vegetation density and less disturbance than surrounding areas can be used to mitigate the effects of urbanization on small mammal populations. Conflict between humans and urban mammals can cause problems for species whose habits can cause damage to properties. An example of this is the management of badger setts. It is more common in urban than in rural areas that wildlife advisers suggest total sett closure of sets which are causing a problem as opposed to other less extreme management strategies (Delahay et al. 2009). The high density of typically small, fenced-off gardens near to buildings provides little room for badgers to create undisturbed setts and they are often unwelcome. Gardens are typically quite small since urban areas need to accommodate a large population. Small gardens separated by fences can impede the movement of mammals who require larger areas of vegetation with little fragmentation, this therefore limits their conservation value for some species (Bateman and Fleming 2012). The red fox Vulpes vulpes has thrived in urban areas and is a frequent visitor of residential gardens, even in areas of intense urbanization (Baker and Harris 2007). The high density of red foxes and the lack of green spaces could mean that other, smaller mammals may be subject to significant predation threats. A popular pet which is present in many UK gardens is the domestic cat Felis catus. Cat predation is another form of threat to small mammals in urban areas, it negatively effects populations of the species they prey upon such as the wood mouse Apodemus sylvaticus (Baker et al. 2005). Cat predation is a difficult factor to control, however it could be reduced by the choice of cat owners to keep cats inside the house more if they are motivated to by conservation efforts. CONCLUSION Urban gardens provide valuable green spaces which aid species dispersal through built up urban areas. They also provide temporary habitats for a wide range of species, the structure and composition of flora in influence which species are likely to visit gardens (McIntyre et al. 2001). The way that household owners manage their gardens influences the wildlife that visit and can therefore be an effective tool for conservation of biodiversity in urban areas. Projects working towards conservation goals tend to involve a large range of stakeholders. It is Matthew Nash therefore helpful if the work has positive socio-political, health or economic benefits as well as ecological impacts so a wide variety of people are motivated to help (Brown 2003). A key issue with using residential gardens as a conservation tool is the fact that these gardens are privately owned and their management can therefore not be regulated. It is therefore of great importance to understand what motivates householder decisions to engage in managing gardens for conservation in order to make residential gardens an effective conservation tool in urban areas (Cook et al. 2011). Research carried out by the RHS found that 70% of respondents would consider wildlife gardening, this would provide a large amount of land for conservation efforts (Thompson et al. 2007). Research has been conducted which suggests that 8% of species on the terrestrial vertebrate species which are on the IUCN Red List are largely threatened by urbanization (McDonald et al. 2008). This means that urban development is negatively impacting a significant proportion of animals which we are trying to conserve. As urban areas continue to expand residential gardens and public education on conservation matters are going to become increasingly important in aiding conservation on local and global scales. In a typical UK city, the area of gardens is larger than the area of parks and woodland combined, this gives residential gardens a huge potential to aid conservation goals (Dunnett and Qasim 2000). The crucial requirement for urban gardens to be used effectively for conservation is the motivation of householders and providing available education of how to do so. References Baker, Bentley, Ansell, Harris. (2005) Impact of predation by domestic cats Felis catus in an urban area. Mammal Review. 35. 302–312. Baker, Harris. (2007) Urban mammals: what does the future hold? An analysis of the factors affecting patterns of use of residential gardens in Great Britain. Mammal Review. 37. 4. 297-315. Bateman, Fleming. (2012) Big city life: carnivores in urban environments. Journal of Zoology. 287. 1. 1-23. Bates, Sadler, Fairbrass, Falk, Hale. (2011) Changing Bee and Hoverfly Pollinator Assemblages along an Urban-Rural Gradient. PLoS ONE. 6. Bergerot B, Fontaine B, Renard M, Cadi A, Julliard R. (2010) Preferences for exotic flowers do not promote urban life in butterflies. Landscape and Urban Planning. 96. 98–107. Biesmeijer, Roberts, Reemer, Ohlemuller, Edwards. (2006) Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science. 313: 351–354 Bolger, Scott, Rotenberry. (1997) Breeding bird abundance in an urbanizing landscape in coastal Southern California. Conservation Biology. 11. 406–42. Brown K. (2003). Three challenges for a real people-centered conservation. Global Ecology and Biogeography 12. 89–92. Chace, Walsh. (2006). Urban effects on native avifauna: A review. Landscape and Urban Planning. 74. 46–69. Cook E, Hall S, Larson K. (2011) Residential landscapes as social-ecological systems: a synthesis of multi-scalar interactions between people and their home environment. Urban Ecosystems. 1- 34. Matthew Nash Corbet, Bee, Dasmahapatra, Gale, Gorringe, La Ferla, Moorhouse, Trevail, Van Bergen, Yorontsova. (2001) Native or exotic? Double or single? Evaluating plants for pollinator-friendly gardens. Annals of Botany. 87. 219–232. Davies et al. (2009) A national scale inventory of resource provision for biodiversity within domestic gardens. Biological Conservation. 142. 761–771. Defra Rural Statistics (2013) The Rural – Urban Classification for England. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/248666 /Rural-Urban_Classification_leaflet__Sept_2013_.pdf (Accessed: 13/10/2014). Delahay, Davison, Poole, Matthews, Wilson, Heydon, Roper. (2009), Managing conflict between humans and wildlife: trends in licensed operations to resolve problems with badgers Meles meles in England. Mammal Review. 39. 53–66. Dickman, Doncaster. (1987) The Ecology of Small Mammals in Urban Habitats. I. Populations in a Patchy Environment. Journal of Animal Ecology. 56. 2. 629-640. Duncan, Young. (2000) Determinants of plant extinction and rarity 145 years after European settlement of Auckland, New Zealand. Ecology. 81. 3048–3061. Dunnett, Qasim. (2000) Perceived benefits to human well-being of urban gardens. Horttechnology. 10. 1. 40-45. Fuller. (2008) Garden bird feeding predicts the structure of urban avian assemblages. Diversity of Distributions. 14. 131–137. Gaston K, Warren P, Thompson K, Smith R. (2005) Urban domestic gardens: The extent of the resource and its associated features. Biodiversity and Conservation. 14. 33273349. Goulson D, Hanley M, Darvill B, Ellis J. (2006). Biotope associations and the decline of bumblebees (Bombus spp.). Journal of Insect Conservation. 10. 95–103. International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. (2000) IUCN guidelines for the prevention of biodiversity loss caused by alien invasive species. Available at: http://www.iucn.org/themes/ssc/pubs/policy/invasivesEng.htm (Accessed: 13/10/2014) Kark, Iwaniuk, Schalimtzek, Banker. (2007) Living in the city: Can anyone become an ‘urban exploiter’? Journal of Biogeography. 34. 638–651. Kearns CA, Oliveras DM. (2009). Environmental factors affecting bee diversity in urban and remote grassland plots in Boulder, Colorado. Journal of Insect Conservation. 13. 655–665. Kremen C, Williams NM, Aizen MA, Gemmill-Herren B, LeBuhn G. (2007) Pollination and other ecosystem services produced by mobile organisms: a conceptual framework for the effects of land-use change. Ecology Letters. 10. 299–314. Liu, Daily, Ehrlich, Luck. (2003) Effects of household dynamics on resource consumption and biodiversity. Nature. 421. 530–533. Loram A, Tratalos J, Warren P.H, Gaston K.J. (2007). Urban domestic gardens (X): the extent & structure of the resource in five major cities. Landscape Ecology. 22, 601–615. Manchester, Bullock. (2000) The impacts of non-native species on UK biodiversity and the effectiveness of control. Journal of Applied Ecology. 37. 845–864. Mason, Moorman, Hess, Sinclair. (2007). Designing suburban greenways to provide habitat for forest-breeding birds. Landscape and Urban Planning. 80. 153-164. Matteson K. (2007) Diversity and conservation of insects in urban gardens: Theoretical and applied implications. ETD Collection for Fordham University. Matthew Nash McDonald, Kareiva, Forman. (2008) The implications of current and future urbanization for global protected areas and biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation. 141. 1695-1703. McKinney. (2002) Urbanization, Biodiversity, and Conservation. The impacts of urbanization on native species are poorly studied, but educating a highly urbanized human population about these impacts can greatly improve species conservation in all ecosystems. Bioscience. 52. 10. 883-890. McIntyre, Rango, Fagan, Faeth. (2001) Ground arthropod community structure in a heterogeneous urban environment. Landscape and Urban Planning. 52. 257–274. Mckinney M. (2008) Effects of urbanization on species richness: A review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosystems. 11, 161-176. ONS (2014) Changes in UK population over the last 50 years. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/pop-estimate/population-estimates-for-uk--englandand-wales--scotland-and-northern-ireland/2013/sty-population-changes.html (Accessed: 14/10/2014). Paker, Yom-Tov, Alon-Mozes, Barnea. (2014). The effect of plant richness and urban garden structure on bird species richness, diversity and community structure. Landscape and Urban Planning. 122. 186-195. Rondinini, Doncaster. (2002) Roads as barriers to movement for hedgehogs. Functional Ecology. 16. 504–509. Royal Horticultural Scoiety. (2014) Bluebells as weeds. Available at: https://www.rhs.org.uk/advice/profile?pid=426 (Accessed: 22/10/2014) Saito, Koike. (2013) Distribution of Wild Mammal Assemblages along an Urban–Rural– Forest Landscape Gradient in Warm-Temperate East Asia. PLOS ONE. Available at: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0065464 (Accessed: 18/10/2014) Sandstrom, Khakee, Angelstam. (2006) Ecological diversity of birds in relation to the structure of urban green space. Landscape and Urban Planning. 77. 39-53. Smith, Thompson, Hodgson, Warren, Gaston. (2006) Urban domestic gardens (IX): Composition and richness of the vascular plant flora, and implications for native biodiversity. Biological Conservation. 129. 312-322. Speight R, Hunter M D, Watt A D. (2008). The Ecology of Insects: Concepts and Applications. 2. Blackwell Scientific. Oxford, UK. The World Bank Group (2014) Urban population (% of total). Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS (Accessed: 14/10/2014) Thompson, Austin, Smith, Warren, Angold, Gaston. (2003) Urban domestic gardens (1): Putting small-scale plant diversity in context. Journal of Vegetation Science. 14. 7178. Thompson, Colsell, Carpenter, Smith ,Warren, Gaston. (2005). Urban domestic gardens (VII): a preliminary survey of soil seed banks. Seed Science Research. 15. 133-141. Thompson, Corkery, Judd. (2007) The role of community gardens in sustaining healthy communities. In Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities National Conference. United Nations Development Programme. (2000) World Resources 2000–2001: People and Ecosystems – the Fraying Web of Life. Elsevier Science. Amsterdam.