BLAKE V AND V SAMPLE SAC

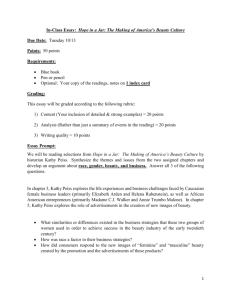

advertisement

William Blake’s Romantic poetry explores the hidden facets of society’s citizens, such as women and children as well as critiquing the social conventions established by the institutions of his society. He encompasses the narrative of the innocent to associate holy denunciation of sexuality with the female. Similarly, from a post-colonial perspective, Blake insinuates that men are attempting to colonise the female to conform to ascetic values. Blake also denigrates the oppressive nature of society against beauty through applying an ancient mythological tales throughout his lyrical poetry. The same concept of suppressing natural beauty can be interpreted through a feminist critique by looking at man’s incapacity to reign their desirous thoughts; which they attempt to control through subduing the effects of womanly beauty. However, through all of William Blake’s work is the reoccurring respect for the natural world, and its capacity to aid man in revolutionizing the culture. Blake abstractedly uses a naïve narrative to criticize society’s condemnation of sexuality, particularly associated with the feminine. In his poem the ‘Sick Rose’ the ‘crimson’ rose exists as a natural object that has become infected by the ‘invisible worm’. The ominous ABCB rhythm of the poem contributes to the poem’s sense of foreboding, or dread, and compliments the unflinching directness of the narrative voice in describing the industrial worm’s ‘dark secret love’ which ‘does thy life destroy’. The image of the worm, ‘that flies in the night’, resonates with the Biblical serpent, yet, simultaneously creates phallic imagery. The religious connotation of the ‘worm’ suggests the persecution of overt female sexuality due to the monogamous attitude of Christianity, which denigrates any wanton display of promiscuity in society. However, this is juxtaposed by its concurrent phallic imaginings alluding to a patriarchal domination over society, represented through their ‘dark secret love’, which is unconsented by the entity of the feminine ‘rose’. The contrast between the ‘Rose’ and the ‘worm’ demonstrates the degradation of sexualized femininity from the insidious phallus of social conventions. Blake uses this degradation to align himself with Wollstonecraft ideology which attacks the existence of the male vindication of women within society; and criticizes the oppression of sexuality, while simultaneously endorsing an expression of ‘crimson joy’. The ‘crimson joy’ symbolically alludes to virginal blood which leaks onto ‘thy bed’ illustrating a sinister domination of the ‘howling storm’ of society through the implied rape of the ‘rose’ by the ‘invisible worm’. This allegorically represents the naivety of the sexual, as shown through the eyes of feminine. The naivety is shown through the first two stanzas in which the narrative voice tells the rose ‘thou art sick’, suggesting the rose was not aware of its infection. This lack of personal awareness demonstrates that females are not aware of their own sexual nature. Similarly, in ‘Mary’ the AABB rhyming scheme of the poem creates a nursery rhythm which enforces the childish, and innocent, narrative when describing the judgment of ‘sweet Mary’. The first two stanzas develop a utopian view of oneself through the eyes of Mary during ‘the first time’ she came ‘among the fair’, suggesting that without the pressure of social conventions an individual remains positive and idyllic. However, the remaining stanzas juxtapose the beginning through whimsically condemning Mary to a ‘whore’ causing ‘her lilies & roses’ to ‘[blight] and shed’. This juxtaposition demonstrates Blake’s reproach for social institutions, as shown through the ‘eyes of disdain’ in the ‘Ball Room’, warping the collective mind to ostracize a display the sexuality of ‘soft beauty and conscious delight’ that is prevalent within the anatomy of the female body. The Christian iconography alluded to throughout the poem like the ‘lamb’ and ‘Christian Love’ focuses Blake’s attack on the institutionalized religion during the early nineteenth century; enforcing his Romantic idealism for embracing sexual identity and worship of the female’s ‘brilliant ray’ of beauty, criticized during Blake’s life. Overall, both the ‘Sick Rose’ and ‘Mary’ illustrate the withering emergence of womanly sexuality due to smothering social conventions enforced by institutionalism. On the other hand, interpreting both the ‘Sick Rose’ and ‘Mary’ from an alternate perspective the ‘invisible worm’ and ‘Envious Race’ represent the masculine colonization against the unconstrained female body, which imperceptibly symbolises the untainted natural landscape, as shown through the ‘Rose’ and ‘different face’ of Mary. The industrialised ‘men’ force the natural savage beauty to conform to the ‘howling storm’ of social etiquette, which only results in creating a civilized ‘Face of mild sorrow’. This forced conformation of the unrestrained ‘Human Divine’ demonstrates the appropriation of sexual awareness, which the institutionalized ‘invisible worm’ and ‘eyes of disdain’ aim to achieve; to create a utopian civilized society. Blake’s generalization that all of society’s aims to constrain the naturalistic feminine semiotically represents that the conventions of institution similarly generalize the values of society; Blake aptly disapproves this through his idolization of the female product- used as an article of trade rather than a human being. This manufacturement of females is reminiscent of the way society uses their body as a service, which is than discarded once it is impure, and lacking ‘dark secret love’. He gives the narrative voice of the appropriated female entities insinuating his endorsement for the reverence of the sexual female being. Blake uses the ‘wild terror’ of parasitical man, and by extension society, to urge a return to naturalness and criticizes society’s industrial prisons, entrapping all the ‘crimson’ roses and ‘divine’ Mary’s. ‘The Sick Rose’ and ‘Mary’ establish the concept that patriarchal suppression of matriarchy is indicative of a desire to colonise the feminine body and forcefully constrain it within social conventions, in an attempt to make it an industrial tool. Blake mythically criticizes the oppression of beauty through appreciating the naturalness of the human form. In the poem ‘[Song] How sweet I roam’d from field to field’, Blake utilizes the mythological story of the God of Love, Eros, and a mortal girl, Psyche; to create an ethereal admiration for the exquisiteness of the ‘golden pleasures’ of humanity. These ‘golden pleasures’ allude to the pleasure man takes from appreciating beauty, in not only the human form but throughout nature. Blake heavily endorses admiration for splendor in a natural format through his angelic description of the ‘golden’ narrator, demonstrating his romantic idealism for a natural landscape and organism. The melodic ABAB rhythm of the poem strengthens the optimistic language used by Blake, such as ‘glide’ and ‘pride’, to create an image of beauty within the words themselves which is maintained throughout the four stanzas. The adoring words of the narrator, detailing the ‘prince of love’ shutting them ‘in his golden cage’ contradict the underlying oppression of attractive physicality; through the oxymoronic entrapment in a ‘silken net’ which ‘mocks [their] loss of liberty’. The ‘loss of liberty’ refers to society’s censorship on the performance of the feminine; where the ‘blushing rose’ of beauty is adorned in the Wollstonecraftian barren blossom of false physicality. This performance endorses superficial appreciation of physical beings but denigrates their beauty through commodifying it to merely a ‘vocal rage’ of imprisonment and theatricality; contemptuously attacking the sinful thought it creates within the audience, or society. Blake demonstrates the commodification of beauty through the imprisonment of the ‘golden wing’ of desire- a consequence of beauty- and comical ‘laughing’ when the narrator ‘stretches [their] golden wing’. This commodification of beauty represents society’s value in materialism, as a result of growing industrialism, which is creating a culture of envious judgment for the natural. Similarly, in the poem ‘Mary’ Blake critically condemns the ‘Men & Maidens’ of society who ostracize the ‘heavenly’ appearance of natural beauty. Within the poem beauty is condemned by the Christianic ‘envy’ of society, which is enforced by the ‘eyes of disdain’ coming from an institutionalized church. Blake contrasts the characterisation of ‘Mary’ and her ‘face of sweet love’ with the judgmental ‘terror and fear’ of the oppressors of beauty. This contrast emphasises Blake’s denigration for society’s exile of the womanly beauty. The exile of beauty is a result of ‘envy’ and ‘scorn’; envy from the ‘Villagers’ and ‘Children in the street’ who admire the ‘brilliant ray’ of Mary’s beauty; and scorn from the Church due to their value in ‘plain neat attire’ as the appropriate image for people. These separate evaluations for the presence of beauty in society demonstrates the ingrained value of monogamy- eliciting that any physical temptations are not tolerated because they detract from people’s, particularly men, ability to remain monogamous. Blake’s criticism for the subjugation of natural beauty stems from his idealized vision of nature as an essential beautiful creation. Whilst he endorses a religious reverence for nature from Christian ideals, yet, simultaneously critiques the role of the institution of the Church of England. Overall, the two poems demonstrate the societal appropriation of natural beauty within a feminine landscape, and, simultaneously, illustrate Blake’s individualistic appreciation for beauty in a physical and spiritual format. Interpreting ‘[Song] How sweet I roam’d from field to field’ and ‘Mary’ from an unconventional perspective; society’s oppression of beauty stems from man’s inability to constraint their desirous thoughts; and they subdue provocative beauty as a means to control their wanton ideas. The ‘Envious Race’ who ‘bespattered’ Mary with ‘mire’ are symbolic of the patriarchal repression of ‘soft beauty’ because of their lack of control over their desire. The undertone of masculinity throughout the poem is signified by the reoccurring Christian iconography of ‘dove’ and ‘divine’ which is typically dominated by men and; also becomes the driving force behind the male conquest over beauty. This is further relevant within the narration of ‘How sweet I roam’d’ through the continual reference to ‘golden’ incarceration. The repetition of ‘golden’ which is juxtaposedly aligned with imprisonment develops the idea of a metaphysical ‘cage’ to coerce beauty into a ‘silken net’. The masculine suppression of feminine ‘delight’ is a consequence of their society’s ecclesiastical aversion to ‘the joys of the night’, conflicting with their semi-conscious temptations concerning the ‘golden wings’ of beauty. This confliction results in the ‘foul fiends’ of masculinity ‘mock[ing]’ the ‘loss of liberty’ females find within the freedom to revel in the ‘golden pleasures’ their beauty provides. Both, ‘[Song] How sweet I roam’d’ and ‘Mary’ represent the masculine vindication against a females’ beauty due to the tempestuous nature of their form. William Blake’s poetry explores the importance of nature in connection with the human form. The poems ‘The Sick Rose’ and ‘Mary’ are reminiscent of the early nineteenth century’s domination over the female form. This is also interpreted post-colonially through semiotically depicting the overpowering of femininity as a masculine attempt to remove wanton thoughts concerning the womanly form. Similarly, in the poems ‘[Song] How sweet I roam’d from field to field’ and ‘Mary’ criticize the denigration of beauty by social conventions. However, from a feminist reading this is interpreted as masculine criticism on feminine tempestuous physicality. Throughout all of William Blake’s poetry he criticizes the industrial landscape emerging in his society, and creates the image of a utopia where man uses nature to evolve not machine. Knowledge and Skills Understanding of the context/s in which the text was set or created. Analysis of the ways in which views and values are suggested by what the text endorses, challenges or leaves unquestioned. Understanding of the ways in which the text provides a critique of human behaviour or aspects of society and/or of the ways in which readers in a different cultural context may arrive at different interpretations. Ability to justify an interpretation through close attention to, selection and use of significant textual detail. Expressive, coherent and fluent development of ideas. Descriptor Thorough understanding of the context/s in which the text was set or created. 5 Detailed understanding of the context/s in which the text was set or created. 4 Sound knowledge of the context/s in which the text was set or created. 3 Some knowledge of the context/s in which the text was set or created. 2 Limited knowledge of the context/s in which the text was set or created. 1 Comprehensive analysis of the ways in which views and values are suggested by what the text endorses, challenges or leaves unquestioned. 5 Complex analysis of the ways in which views and values are suggested by what the text endorses, challenges or leaves unquestioned. 4 Clear analysis of the ways in which views and values are suggested by what the text endorses, challenges or leaves unquestioned. 3 Limited analysis of the ways in which views and values are suggested by what the text endorses, challenges or leaves unquestioned. 2 Little analysis of the ways in which views and values are suggested by what the text endorses, challenges or leaves unquestioned. 1 Sophisticated understanding of the ways in which the text provides a critique of human behaviour or aspects of society and/or of the ways in which readers in a different cultural context may arrive at different interpretations. 5 Complex understanding of the ways in which the text provides a critique of human behaviour or aspects of society and/or of the ways in which readers in a different cultural context may arrive at different interpretations. 4 Some detailed understanding of the ways in which the text provides a critique of human behaviour or aspects of society and/or of the ways in which readers in a different cultural context may arrive at different interpretations. 3 Some understanding of the ways in which the text provides a critique of human behaviour or aspects of society and/or of the ways in which readers in a different cultural context may arrive at different interpretations. Little understanding of the ways in which the text provides a critique of human behaviour or aspects of society and/or of the ways in which readers in a different cultural context may arrive at different interpretations. 2 Highly-developed ability to justify an interpretation through close attention to, selection and use of significant textual detail. 5 Well-developed ability to justify an interpretation through close attention to, selection and use of significant textual detail. 4 Sound ability to justify an interpretation through attention to, selection and use of significant textual detail. 3 Some ability to justify an interpretation through attention to, selection and use of textual detail. 2 Limited ability to justify an interpretation through attention to, selection and use of textual detail. 1 Very expressive, coherent and fluent development of ideas. 5 Expressive, coherent and fluent development of ideas. 4 1 Coherent and clear development of ideas. 3 Clear expression of ideas. 2 Simple expression of ideas. 1